Depression and bipolar illness in the workplace impair productivity and are dearly expensive, as multiple studies have documented for decades (

1,

2). One would assume that such reports would have fueled widespread concern and action, but they have not, despite huge potential payoffs.

Various reasons help explain why. First, economists speak a different language than translational neuroscientists, psychopharmacologists, and psychotherapists, and they tend to study productivity and cost measures separately from clinical outcomes. Second, there are minimal funding streams to evaluate or sustain workplace initiatives. Third, stigma hamstrings access in workplace settings, prompting many business leaders to be skeptical that any endeavor will work. Fourth, depressions have multiple etiologies; one-size treatment will never fit all, yet that approach dominates clinical practice. Fifth, psychiatric investigators generally fail to include evaluations of the questions that most interest employers, such as the following: Do improvements in depressive symptoms produce productivity improvements and overall cost reductions? Can effective symptom improvement in depressed individuals in workplace settings be reliably achieved and sustained? Will the development of programs addressing workplace depression produce favorable returns on investment and improve the financial bottom line?

The most important findings in the report by Trivedi et al. in this issue (

3) address a few of these neglected issues. Trivedi et al. evaluated 1,928 adult outpatients with depression who were treated with citalopram according to the well-described Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) guidelines, and they wisely added the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment scale. Their first major finding affirms previous reports: individuals with depression reported 4–5 times the impairment in work productivity than those without depression. This is the old news. Second and far more important, the authors reported that work productivity in several domains

improved with reductions in depressive symptom severity during successful initial (acute-phase) treatment. The authors’ third observation fires a warning shot: productivity improvements were observed only in the earliest phase of treatment. Workers who did not achieve symptom remission until later stages continued to manifest impairment at work. The finding that productivity improved among workers who attained wellness with early treatment is a clarion call for greater partnerships among the business and brain-science worlds in efforts to combat depression in the workforce.

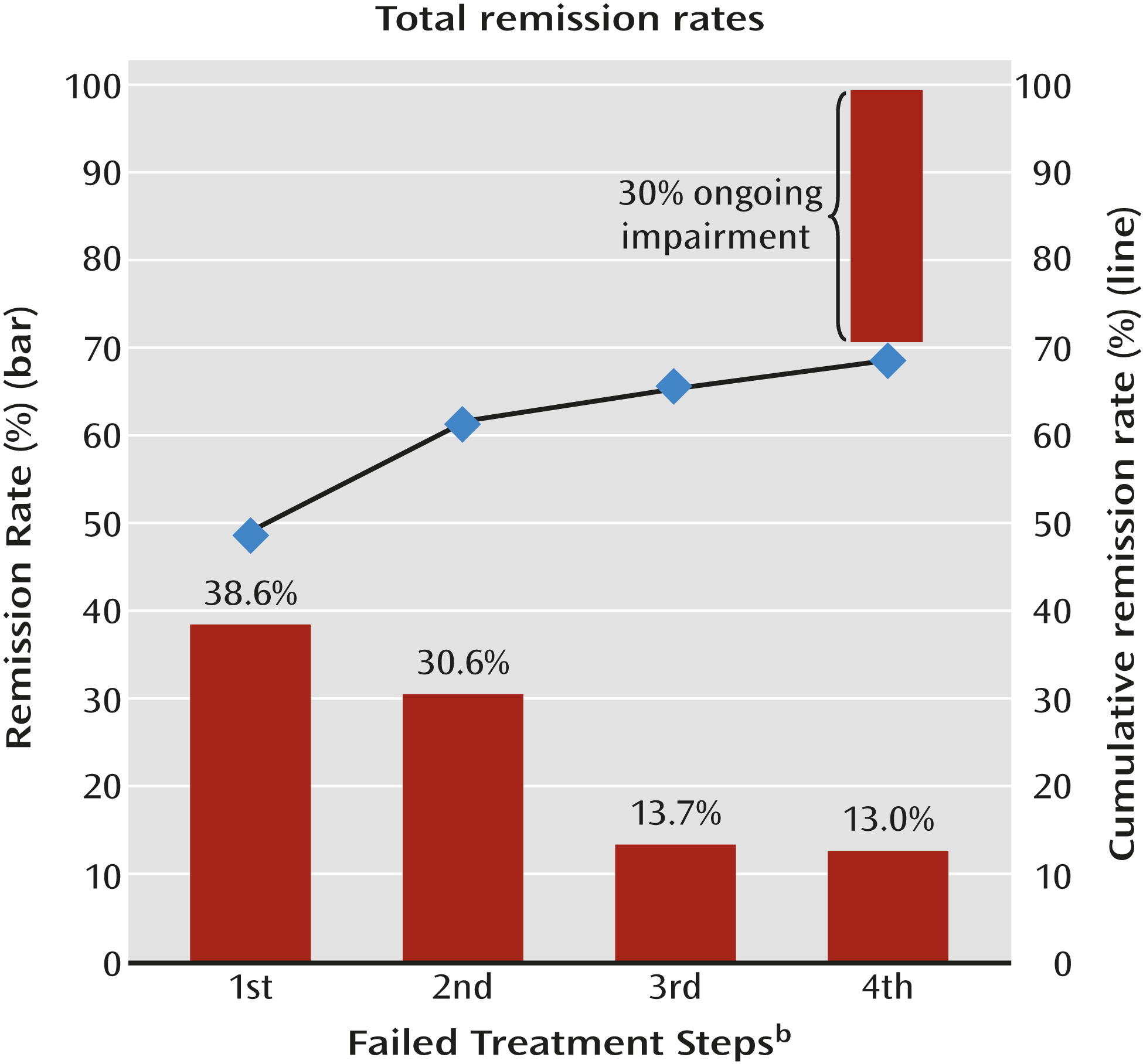

Outcomes from the overall STAR*D project (

4) (

Figure 1) help explain why clinical outcome assessments and business concerns should be brought together to tackle important workplace concerns. In STAR*D, initial treatment (level 1) with citalopram, an established first-line agent, brought about remission in less than 40% of participants. These early responders were the only subgroup in the Trivedi et al. study (

3) who reported increased workplace productivity. After a subsequent (level 2) switch or augmentation treatment course, only about 30% of those who remained in a depressive episode after level 1 attained remission. These later responders did not report increased workplace productivity. The reasons for this remain to be determined, but considerable evidence indicates that depression’s chronicity takes a toll on brain function. Even more ominously, after four treatment courses in the overall STAR*D sample, about 30% of participants had not attained remission. Individuals with treatment-resistant depressions generate the highest workplace costs (

5). Attaining early remission and preventing treatment-resistant depression among workers who develop depressive illnesses would save both lives and money.

What steps need to be taken by mental health investigators and business leaders to begin rolling out this potential? Perhaps most pressing for neuroscientists and mental health investigators, we need to accelerate efforts to develop personalized precision treatments for depression (

6,

7). Failure to respond to current first-line antidepressants is meaningfully linked to the fact that depression has multiple underlying and interactive brain pathophysiologies, such as genetic alterations of different neurotransmitter circuits (serotonergic, noradrenergic, glutamatergic); alterations of growth factors such as brain-derived neurotropic factor, nerve growth factor, or fibroblast growth factor 2; immunological and inflammatory disorders (such as interleukin-6-related disorders); trauma; and others. Comparable to other major medical disorders, the right treatment needs to be found for the underlying pathophysiologies at the right time.

Imagine that 5 years from now, underlying pathophysiologies are better identified before treatment is started and that biomarker and comparative personalized treatment trials enable clinicians to identify another 20% of patients in the first stage of treatment who are far more likely to respond to a glutamatergic intervention than to the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor used in STAR*D level 1 or to agents that counteract interleukin inflammatory processes in the brain. Now, imagine that 60% of patients might be early remitters instead of less than 40%. The productivity jump would be appreciable—and productivity is only the tip of the business iceberg. The total annual cost of depression to U.S. employers alone is generally reported to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars (

1,

2). So further imagine the impact once it became established, as is likely, that more successful treatment of millions of individuals with depression in workplace settings not only improves productivity but saves millions or billions of dollars for employers, insurers, and society, raises stock prices, and accomplishes all these benefits while treating one of the most disabling diseases in the world. Greater partnerships among business leaders, clinical translational investigators, and clinical delivery networks will be required to roll out such intervention programs on a large scale, but the payoff should be profound.

What steps are necessary to accelerate the process? Clinicians must note that initial treatment failure is a call to alarm and that with each failure, remission rates plummet and relapse rates increase (see

Figure 1). This calls for lessening or abandonment of common current approaches of “watchful waiting” and discontinuation of maintenance treatment for patients with prior episodes. All possible steps should be taken to achieve earlier detection, requiring a greater emphasis on screening, ideally during adolescence (

7),

plus earlier intervention when severity dictates,

plus measurement-based care (using standardized scales) (

8),

plus maintenance of wellness (

5,

9). These consolidated approaches should be the standard of care, and special attention must be given to earlier recognition of the threat of treatment-resistant depression, taking an array of steps to prevent its development (

5).

For those who prioritize research directions, the search for biomarkers and personalized treatment strategies should be accelerated in large, standardized, longitudinal samples. Next-generation sequencing and concomitant assessment of promising biomarkers will need to be applied to large populations, family-based samples, or samples that have been better characterized by strategies such as use of induced pluripotent stem cells, and then coupled with long-term outcome assessments rather than short-term studies. Truly large samples, tens of thousands rather than tens or hundreds, will be required. To achieve this, we must develop sustainable networks with “big-data” capacities. Networks that come and go with brief grant funding will not suffice. Early prototypes such as the National Network of Depression Centers (

10) have been started for depression, bipolar illness, and related conditions, but financial supports will be needed to fully develop their potential.

Business leaders, insurance companies, and anyone who bemoans high health care costs will need to respond to data showing that wellness is a better cost-reducer and productivity-improver than treatment restrictions. The findings by Trivedi et al. in this issue (

3) addressed only productivity gains, but in doing so, the authors provide a tantalizing peek at a promising vision. Full-scale workplace initiatives, network partnerships, personalized treatment development, and prevention programs will promote profitability rather than raising costs. This vision is attainable.