Violence is a defining characteristic of gang membership (

1,

2), together with extensive criminality and substance misuse (

3). Street gangs are increasingly evident in U.K. cities (

1,

4), with similarities to gangs in the United States, where fluctuations in gang activity correspond to changes in homicide rates (

5), youth violence, and victimization (

6,

7). Gun control has resulted in low rates of homicides involving firearms in the United Kingdom, but gang members are estimated to carry out half of all shootings and 22% of serious violent crimes in London (

1). The spread of gang-related violence is held to resemble an epidemiological “core infection” model (

8) through a process of social contagion (

9) in which gangs evaluate and respond to the highly visible violent actions of other gangs, retaliate, and attempt to achieve dominance through violent retribution (

10). Violence is necessary for building and maintaining personal status and enforcing group cohesion, is instrumental in obtaining sexual access and money through robbery and intimidation, and may be a source of excitement. It is essential to the regulation of local drugs markets by organized gangs (

11). Gang violence represents a major public health problem. Gang members engage not only with criminal justice agencies (

1) but also with the health care system, by multiple entry points, particularly trauma services (

2). To our knowledge, no previous research has investigated whether gang violence is related to psychiatric morbidity (other than substance misuse) or places burdens on mental health services. Epidemiological studies have shown that psychiatric morbidity is associated with violent behavior (

12–

15), although the mechanisms involved are complex and are not fully understood. In addition to violence toward others, gang violence can result in high levels of traumatic victimization and fear of violence (

16).

Through their violence, gang members are potentially exposed to multiple risk factors for psychiatric morbidity. Our aim in this study was to investigate associations between gang membership, violent behavior, and psychiatric morbidity in a nationally representative sample of young men and to identify explanatory factors. We examined associations between violent behaviors, attitudes toward and experiences of violence, a range of mental disorders, and use of mental health services. To identify the specific effects of gang membership, we compared gang members with young men who were violent but not in gangs.

Method

Data Collection

We carried out the survey in 2011. It was based on random location sampling, an advanced form of quota sampling shown to reduce the biases introduced when interviewers choose a location to sample from. Individual sampling units (census areas of 150 households each) were randomly selected within British regions, in proportion to their population. The basic survey derived a representative sample of young men (18–34 years of age) from England, Scotland, and Wales. In addition, there were four boost surveys. First, young black and minority ethnic men were selected from output areas with a minimum of 5% black and minority ethnic inhabitants. Second, young men from the lower social grades (grades D and E, as defined by the Market Research Society, based on head of household: semiskilled, unskilled, and occasional manual workers; and pensioners and welfare recipients) were selected from output areas in which there were a minimum of 30 men 18–64 years of age in these social grades. The final boost surveys were based on output areas in two locations characterized by high gang membership, the London borough of Hackney and Glasgow East, Scotland. The same sampling principles applied to each survey type.

A self-administered questionnaire piloted in a previous survey was adapted for this one. Informed consent was obtained from all survey respondents. Respondents completed the pencil-and-paper questionnaire in privacy and were paid £5 for their participation.

Survey Measures

The Psychosis Screening Questionnaire (

17) was used to screen participants for psychosis; a positive screening was one in which three or more criteria were met. Questions from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders Screening Questionnaire (

18) identified antisocial personality disorder.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (

19) was used to define anxiety and depression, based on a score ≥11 in the past week. Scores ≥20 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (20) and scores ≥25 on the the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (21) were used to identify alcohol or drug dependence, respectively.

Participants were asked if they had ever deliberately attempted to kill themselves. They were also asked whether they were currently taking any prescribed psychotropic medications, had consulted a medical practitioner over the past 12 months for mental health problems, had ever seen a psychiatrist or psychologist, or had ever been admitted to a psychiatric hospital.

Gang Membership and Violence

All participants were questioned about violent behavior, including whether they had been “in a physical fight, assaulted or deliberately hit anyone in the past 5 years,” as used in previous surveys of violence (

13,

15). Information was sought about the number of violent incidents they had been involved in and their attitudes toward and experiences of violence. They were additionally asked, “Are you currently a member of a gang?” For inclusion in the study, gang members had to endorse gang membership and one or more of the following: serious criminal activities or convictions, involvement with friends in criminal activities, or involvement in gang fights during the past 5 years.

Participants were divided into three mutually exclusive groups according to participation in violence and gang membership: 1) nonviolent men—participants reporting no violent behavior over the past 5 years and no gang membership; 2) violent men—participants reporting violence over the past 5 years but no gang membership or involvement in gang fights; and 3) gang members.

Statistical Analysis

Initially, we compared the demographic characteristics of nonviolent men, violent men, and gang members using logistic regressions to identify potential confounders. Three analyses were performed, comparing nonviolent men and violent men, nonviolent men and gang members, and violent men and gang members.

Differences between the nonviolent men, the violent men, and the gang members with respect to psychopathology and service use were established by performing logistic regression analyses in the three comparison groups. Linear trends were established by entering group membership as an ordinal variable. As above, three analyses were conducted, comparing nonviolent men and violent men, nonviolent men and gang members, and violent men and gang members.

Finally, we investigated whether associations between 1) gang membership, 2) violence, and 3) psychopathology or service use were explained by attitudes toward violence, victimization experiences, and characteristics of violent behaviors. Potential explanatory variables were first identified by testing their association with 1) gang membership or violence and 2) psychopathology or service use. Only if both associations were significant at an alpha level of 0.05 were variables selected and then entered in an adjusted model, with group membership as the independent variable and psychopathology or service use as the dependent variable. We examined the percentage reduction in the baseline odds of each mental disorder and type of service use after adding each of the potentially explanatory variables into the following equation: (βunadjusted − βadjusted) / βunadjusted × 100. In a final model, all explanatory variables were entered simultaneously. Comparisons between baseline-adjusted and fully adjusted coefficients were used to estimate the extent to which the association between group membership and psychopathology or service use was accounted for by the explanatory variable.

To control for differences between samples, survey type was included as a covariate in all analyses. We also used robust standard errors to account for correlations within survey areas because of clustering within postal codes. An alpha level of 0.05 was adopted throughout. All analyses were performed in Stata, version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex.).

Discussion

We found inordinately high levels of psychiatric morbidity and associated health service use among young British men who are gang members. Street gangs are concentrated in inner urban areas characterized by socioeconomic deprivation, high crime rates, and multiple social problems (

1). One percent of men 18–34 years of age in Great Britain are gang members, compared with 8.6% in the London borough of Hackney, where 1 in 5 black men in that age group reported gang membership. Our findings imply that gang members make a large contribution to mental health disability and burden on mental health services in these areas. This represents an important public health problem, previously unreported.

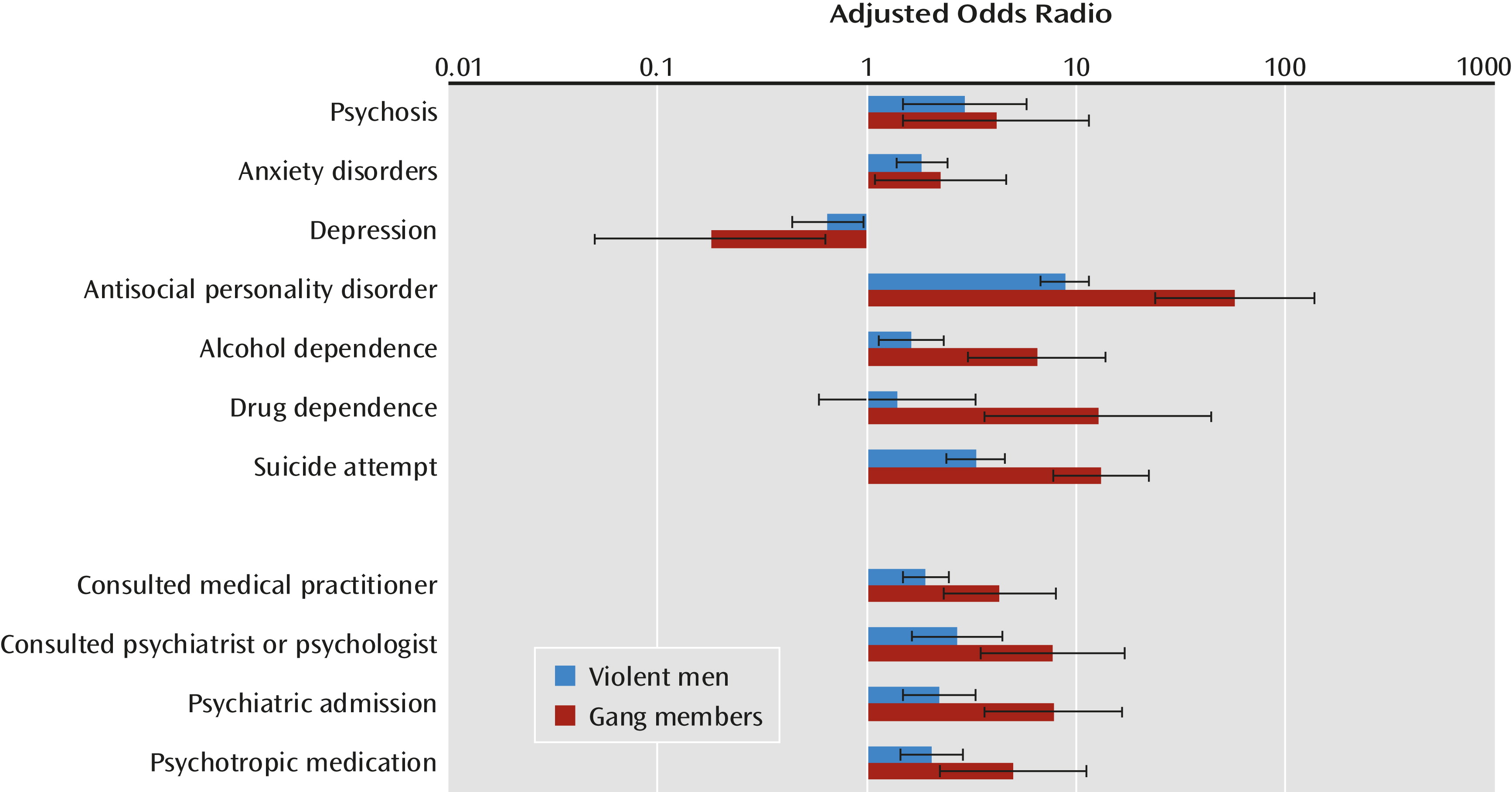

We found a marked gradient in level of psychopathology across the three groups. In general, mental disorders were more prevalent among violent men and gang members than among nonviolent men, and both groups reported significantly higher use of psychiatric services. However, depression was

less prevalent among violent men and gang members. Violence can be construed as one of several displacement activities and mechanisms for enhancing self-esteem that are used to reduce the deleterious effects of negative environment, including childhood maltreatment and educational failure (

22). However, since we cannot determine the direction of association, it is equally possible that higher levels of depression resulted in a reduction of violence because depressed individuals are less inclined or able to behave violently.

Violent men did not differ from the nonviolent reference group with respect to their relatively low prevalence of drug dependence. In contrast, over half of gang members had drug dependence. This is unsurprising given the large proportion of gang members actively involved in the underground drug economy.

The associations with antisocial personality disorder were unsurprising, as violence before age 15 persisting into adulthood is a criterion for this diagnosis. Criminality and violence both demonstrate escalation in frequency during gang membership (

23). Associations with lifetime suicide attempts may partly reflect other psychiatric morbidity, including anxiety disorders and depression. However, they also correspond to the notion that impulsive violence may be directed both outward and inward (

24). The relationship between alcohol misuse and violence is highly complex (

25). However, heavy alcohol use is a well-documented aspect of gang life (

26) and a well-established risk factor for violent behavior.

The high prevalences of anxiety disorders and positive screening for psychosis among gang members were unexpected. Although psychotic illness and psychiatric admissions are more common in inner urban areas, including those characterized by gang violence, these factors could have provided only a partial explanation. This issue warrants further investigation.

Characteristics of Violence

Violence is commonly reported by young men, and 1 in 3 of our nationally representative sample reported getting into a fight or assaulting someone in the past 5 years. Correspondingly, fear of violent victimization was relatively high even among young British men who did not report violence. Nevertheless, rates of violent victimization and fear of violent victimization were significantly higher among violent men and greater still among gang members. Frequent violent ruminations and the propensity to react violently to perceived disrespect differentiated violent and nonviolent men but were highest in gang members.

There were quantitative and qualitative differences in the violence of gang members and other violent men. Instrumental (purposeful) violence was a defining characteristic of gang activity, as was repetitive violence. Gang members were also more likely to report violent ruminations, excitement from violence, and being prepared to be violent if disrespected. They were correspondingly more likely to have criminal convictions for violence.

Can the Associations With Psychopathology and Service Use Be Explained by Characteristics of Violence?

Given that violent men and gang members were significantly more likely to have positive attitudes toward violence, more experiences of violence, and fear of violent victimization and that violence among gang members was qualitatively different than among violent men, we investigated whether these factors explained the increased psychiatric morbidity and service use in these groups. We found that none of these variables explained the high levels of alcohol and drug dependence, antisocial personality disorder, and suicide attempts or the lower rates of depression, suggesting that they were accounted for by other, unmeasured, variables. However, the combination of violent ruminations, experiences of being violently victimized, and fear of future victimization explained associations of gang membership with both anxiety disorders and psychosis. Violent men who were not gang members also reported significantly higher levels of anxiety disorders. However, in contrast to gang members, their anxiety was not explained by violent characteristics as demonstrated for gang members, suggesting that the causes of anxiety in gang members differ from those of other violent young men.

The high levels of consultations with psychiatrists or psychologists among violent men and gang members were accounted for by their fear of, and actual experiences of, violent victimization. These variables, together with violent ruminations, also explained their high rates of admission to psychiatric hospitals, suggesting the importance of violent traumatization in determining service use. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the most frequent psychiatric outcome of exposure to violence. Epidemiological surveys suggest that 15%−24% of those exposed will develop PTSD, with the highest risk following violent assault (

27). Psychotic symptoms frequently occur in PTSD (

28) and have been reported as particularly frequent among military combat veterans (

29). Additional symptoms include anxiety and misuse of alcohol. It has been suggested that gang membership increases the risk of posttraumatic stress (

30). Furthermore, a combination of PTSD and psychotic illness is associated with high levels of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral disturbance, including violent ruminations and behaviors (

31). It is probable that among gang members, high levels of anxiety disorders and psychosis were explained by PTSD. However, this would only partly explain the high prevalence of positive screens for psychosis in gang members. Psychosis is more likely than PTSD to lead to psychiatric hospitalization in the United Kingdom. Further research should determine whether the high prevalence of positive screens for psychosis among gang members was explained by psychotic illness or severe PTSD with psychotic symptoms.

Limitations

Our survey had several limitations, including the definition used to determine gang membership. However, there is no consensus about definition because gang structures have considerable heterogeneity. Nevertheless, we included three of the five U.K. criminal justice agency criteria (

1) that could be captured using self-report, covering predominantly street-based individuals who see themselves as a discernible group, engage in criminal activity or violence, and are in conflict with similar gangs. However, because participants were 18–34 years of age and the mean age for gang membership in the United Kingdom is 15 years, gang members in this study should be considered “core” members who have not desisted by early adulthood. Longitudinal study is needed to investigate whether age and remaining in the gang were key factors determining our findings (

32). Furthermore, U.S. national surveillance studies of gangs have observed longitudinal trends of increased prevalence of gang members 18 years and above.

Violent behavior within the past 5 years was also assessed by self-report and did not include objective information, such as data on arrests or convictions. Self-report may have underestimated the true prevalence because socially undesirable behaviors tend to be less frequently reported. Diagnoses were also derived from self-report questionnaires and not confirmed by clinical interview, although self-report instruments can compare favorably with clinicians’ assessments (

33). Furthermore, prevalences of mental disorders among young men in two previous surveys in Great Britain (

34,

35) were similar to those of nonviolent men in this survey.

Dating of episodes of mental disorders proved difficult, and we did not identify whether violent incidents related to times when symptoms were present. However, the community-based design and large sample size allowed us to examine associations between different categories of mental disorders and violent behavior, thus avoiding the selection bias associated with clinical samples. Furthermore, the sample size provided sufficient statistical power to test complex models and to control for confounding from demographic characteristics and comorbidity.

Implications

Our study highlights a complex public health problem at the intersection of violence, substance misuse, and mental health problems among young men. Gang membership and involvement in gang violence should be routinely assessed in young men presenting to health care services with psychiatric morbidity in inner urban areas with high levels of gang activity. Risk of relapse and failed intervention are elevated among those who return to gang activities, and gang members should be helped to understand the risks to their mental health. Readiness to retaliate violently if disrespected, excitement from violence, and short-term benefits from instrumental violence lead to further cycles of violence and risk of violent victimization (

36). Our study suggests that these factors can increase anxiety to a level that requires treatment and can increase the risk of psychotic symptoms. Substance misuse, while temporarily increasing excitement and reducing the associated anxiety, may increase anxiety and paranoid thinking in the long term and be accompanied by additional addictive behaviors (

37).

Further research is needed on effective interventions for gang members with psychiatric morbidity. Other risk factors that were not measured here but to which gang members are more frequently exposed are likely to contribute to a high prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and use of health care services—for example, involvement in the underground drug economy and drug dependence, which may increase risk for other psychiatric disorders irrespective of involvement in violence. Nevertheless, violent victimization and fear of further violence were predominant explanations for high levels of service use. Violent victimization is an important motivator for leaving the gang (

38), suggesting that health care professionals may have a key role in helping gang members disassociate from gang activities.