To the Editor: Schizophrenia is often characterized by poor psychosocial functioning, which in turn has been linked to clinical features such as anhedonia and diminished general well-being, as measured by constructs such as subjective quality of life (

1). However, some evidence, including research from our own group, argues against the notion that individuals with schizophrenia are by definition anhedonic (

2) and has demonstrated that despite marked functional impairment, individuals with schizophrenia are as happy as healthy comparison subjects (

3).

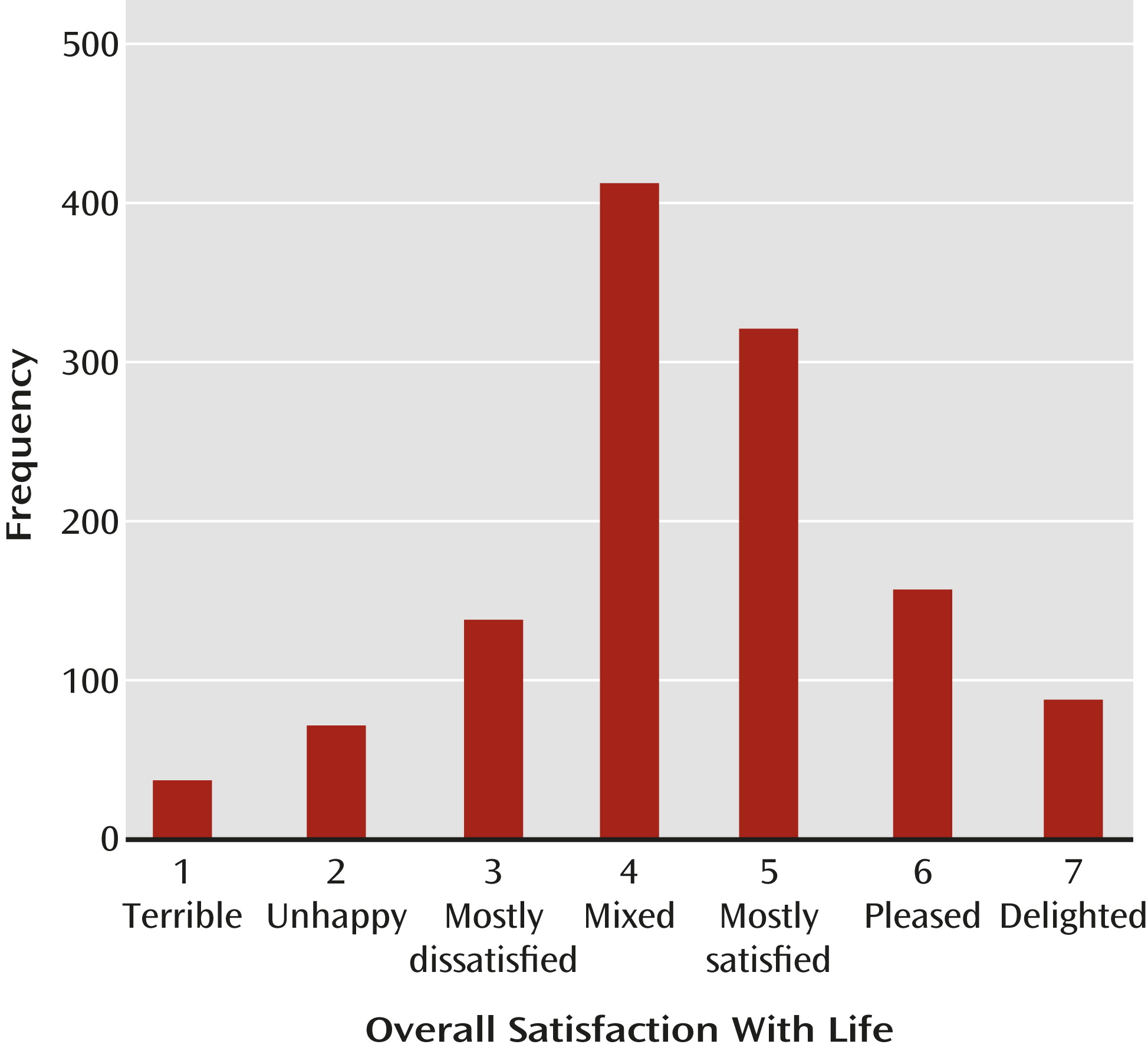

To explore this issue further, we used data from the CATIE schizophrenia study to examine the prevalence and consequences of overall satisfaction with life among individuals with chronic schizophrenia. We found that 46% of patients (N=1,224 total, excluding those with a current major depressive episode) were generally satisfied with their life (

Figure 1). This rate is striking, especially given that the sample was symptomatic (i.e., they were entering a treatment trial), and may actually be higher in stable patients.

Individuals who rated themselves as being satisfied with life had fewer positive and depressive symptoms and better psychosocial functioning (t values >3 in all cases, df=1,219, p<0.002). Fewer psychotic symptoms suggest that ratings of happiness were not merely secondary to reality distortion; moreover, this group did not differ in terms of negative symptoms, neurocognition, or clinical insight compared with those less satisfied with life (t values <1.8 in all cases, df=1,219, p>0.05). The instruments employed to assess these symptoms have been reported elsewhere (

4).

Longitudinally, the majority (76%) of these satisfied patients remained so after 6 months despite no significant improvements in psychosocial functioning (t=−1.9, df=357, p=0.06, Cohen’s d=0.2). This result is somewhat intuitive, as we would not expect individuals to strive for change if they were satisfied with their current situation. Of note, it has been reported that individuals with schizophrenia overestimate their level of functioning and environmental assets (

1). Both biological and psychological factors have been implicated (

3), although underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Our findings here affirm that level of functioning is not without importance, and it remains that many individuals are in fact not satisfied. Those individuals involved in care need to be aware that patients with schizophrenia, even early in the illness’ course (

3), may undergo a considerable shift in terms of goals and values. This clearly affects rehabilitation efforts and may, at least in part, explain the difficulty engaging individuals in programs that fail to take this into account.