Violence toward others among military veterans is an issue of increasing concern (

1–

5). Research has examined violent behavior among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (

2–

6) and previous eras of service (

7–

11). To date, however, clinicians have little direction for gauging what level of risk a veteran might pose in the future (

12). Admission and discharge decisions and community treatment planning would be enhanced by research that directly informs, and possibly improves, decision making and resource allocation in these clinical contexts (

13).

Evaluations grounded in a structured framework and informed by empirically supported risk factors improve the assessment of violence (

14–

18). In civilian populations, significant progress has been made toward identifying risk factors empirically related to violence (

17,

19–

21) and combining these statistically into actuarial or structured risk assessment tools—such as the Classification of Violence Risk (

22) and the Historical Clinical Risk Management–20 (HCR-20) (

19), respectively—to aid clinicians conducting a violence risk assessment (

20,

21,

23,

24).

To our knowledge, no comparable research has been conducted with military veterans. Although studies have identified correlates of violence in veterans (

2,

6,

11,

25,

26), to our knowledge, veteran-specific factors have yet to be combined statistically into an empirically supported, clinically useful tool for guiding assessment and treatment in mental health practice. Neither combat exposure nor military duty necessarily places veterans at greater risk of violence than civilians (

13); however, clinical decision support tools incorporating potentially relevant factors unique to veterans (e.g., war zone experience, associated psychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder) are not yet available. In this study, we evaluated the predictive validity of a brief screen to identify veterans at higher risk for violence.

Method

Participants and Procedures

We employed the same measures and 1-year time frame in two sampling frames: a national survey and in-depth assessments of veterans and collateral informants. The national survey queried self-reported violence in a random sample of all veterans who served after September 11, 2001. The in-depth assessments probed multiple sources of violence in a self-selected regional sample of veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Given the strengths and weaknesses of each approach, we reasoned that statistical concordance of a set of risk factors for predicting subsequent violence in two disparate sampling frames would provide a viable basis for a risk screen.

National survey.

The sample for the National Post-Deployment Adjustment Survey, originally drawn by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Environmental Epidemiological Service in May 2009, consisted of a random selection from over 1 million U.S. military service members who served after September 11, 2001, and were, at the time of the survey, either separated from active duty or in the Reserves or National Guard. Veterans were surveyed using the Dillman method (

27), involving multiple, varied contacts to maximize response rates. Two waves of parallel data collection were conducted 1 year apart, and participants were reimbursed after each wave. In this study, we analyzed risk factors at the initial wave and violence at follow-up.

The initial wave of the survey was conducted from July 2009 to April 2010, with a 47% response rate and a 56% cooperation rate, rates comparable to or higher than those of other national surveys of veterans in the United States (

28–

30) and the United Kingdom (

31). Details may be found elsewhere (

32) regarding the sample generalizability of 1,388 veterans who completed the initial assessment; analysis showed little difference in available demographic, military, and clinical variables between those who took the survey after the first invitation and those who responded after reminders; between responders and nonresponders; and between those who completed the survey on paper and those who did so on computer via the Internet.

One-year follow-up was conducted from July 2010 to April 2011, with 1,090 veterans completing an identical follow-up survey (retention rate, 79%). Multiple regression analysis revealed that younger age and lower income predicted attrition, perhaps reflecting higher residential instability; other variables and violence were nonsignificant. Although estimated models accounted for 4% of attrition variance, the achieved retention rate was relatively high. To our knowledge, this national survey enrolled one of the most representative samples of U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan veterans to date.

In-depth assessments.

The second sampling frame involved in-depth assessments of veterans and collateral informants at the Durham VA Medical Center. Participants were self-selected Iraq and Afghanistan veterans recruited through clinician referrals, advertisements, targeted mailings, or enrollment in the VA Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center’s Registry Database for the Study of Post-Deployment Mental Health.

Institutional review board approval was obtained before data collection, which spanned June 2009 to March 2013. To be eligible for the in-depth assessments, veterans must have served in the U.S. military after September 11, 2001 (as in the national survey). Veterans selected a close family member or friend to serve as a collateral informant. If both agreed to participate, data collection was scheduled at the Durham VA Medical Center. All participants provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study. Assessments included self-report measures and face-to-face interviews and were conducted separately with the veteran and collateral informant.

As in the survey, the time frame for the in-depth assessments was 1 year, in which three waves of data collection occurred 6 months apart. For each wave, veterans and collateral informants provided data and were reimbursed. For this study, risk factors at the initial assessment and violence at follow-up assessments were analyzed using measures parallel to those in the national survey. Of the original 320 veteran-collateral informant dyads who completed the initial wave, 197 pairs were retained at 1 year (retention rate, 62%). Attrition was related to male gender and alcohol misuse, accounting for 16% of the variance.

Measures

At initial data collection in the national survey and the in-depth assessments, risk factors were measured based on variables that have been found to be associated with violence in empirical research on veterans (

12). Candidate risk factors included financial instability, combat experience, alcohol misuse, history of violence or arrests, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

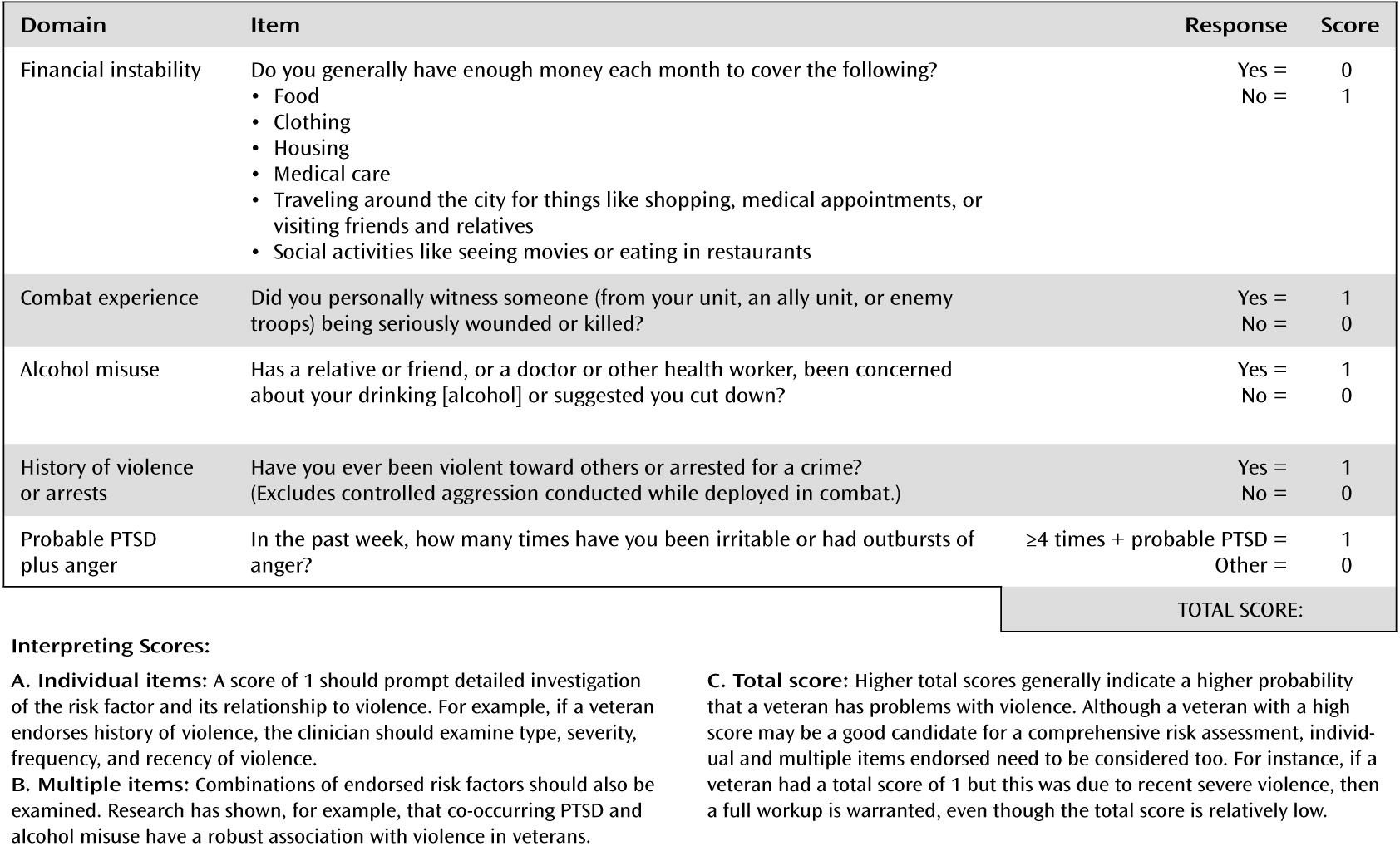

To construct a brief screen, we used single items to measure financial instability and history of violence or arrests. Combat experience, alcohol misuse, and PTSD were originally measured with scales, but in constructing a brief risk screen, we identified the single item on each scale with the strongest statistical association with violence. To do this, we entered scale items into bivariate correlation matrices, repeating this analysis for both sampling frames and at different levels of the violence outcome. From the matrices, we selected the single scale item with the strongest association.

For financial instability, we used an item on the Quality of Life Interview (

33): “Do you generally have enough money each month to cover the following? Food, clothing, housing, medical care, traveling around the city for things like shopping, medical appointments, or visiting friends and relatives, and social activities like seeing movies or eating in restaurants” (0=yes; 1=no).

For combat experience, we examined items from the combat exposure subscale of the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (

34). Endorsing one or both of the following had the most robust relationship with outcomes: “I personally witnessed soldiers from enemy troops being seriously wounded or killed” or “I personally witnessed someone from my unit or an ally unit being seriously wounded or killed” (1=yes; 0=no).

For alcohol misuse, we used the item from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (

35) that showed the strongest correlation with outcomes: “Has a relative or friend, or a doctor or other health worker, been concerned about your drinking or suggested you cut down?” (1=yes; 0=no).

For history of violence and arrests, participants indicated whether they had been arrested or been violent toward others, excluding controlled aggressive behavior conducted during combat duties (1=yes; 0=no).

For PTSD and anger, participants had to meet criteria for probable PTSD on the Davidson Trauma Scale (a score >48) (

36,

37) and report frequent anger on the following item from the scale: “In the past week, how many times have you been irritable or had outbursts of anger?” (1=≥4 times plus probable PTSD; 0=other).

For the follow-ups in both sampling frames, violent behavior was operationalized as in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study (

17). Severe violence was coded 1 if the participant endorsed specific items on the Conflict Tactics Scale (

38) (“Used a knife or gun,” “Beat up the other person,” or “Threatened the other person with a knife or gun”) or the MacArthur Community Violence Scale (

39) (“Did you threaten anyone with a gun or knife or other lethal weapon in your hand?” “Did you use a knife or fire a gun at anyone?” or “Did you try to physically force anyone to have sex against his or her will?”) in the past year. Other physical aggression was coded 1 if the participant endorsed other items on these scales (kicking, slapping, using fists, and getting into fights) in the past year. A composite of any violent behavior was coded 1 if the participant endorsed severe violence or other physical aggression in the past year.

Identical questions and coding for dependent variables were used in both sampling frames. The surveys measured violence/aggression by self-report at a 1-year follow-up, whereas the in-depth assessments occurred at 6 months and 1 year and gathered information about veterans’ violence/aggression from self-report and collateral sources. Research has found considerable agreement between veteran self-report and collateral reports of violence; a veteran study that used both self-report and collateral reports to measure violence (

40) revealed that 80% of cases positive for violence could be determined by self-report alone, without use of the collateral reports. This finding is consistent with civilian studies using multiple sources for measuring violence (

41).

Statistical Analysis

SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) was used for analyses. For the national survey, women were oversampled to ensure adequate representation. Women comprised 33% of the survey sample but 15.6% of the military at the time of data collection (

42); accordingly, survey data were down-weighted to reflect the prevailing military proportion, rendering a weight-adjusted sample size of 866. In-depth assessments were not weight-adjusted but included collateral information on violence.

Statistical analyses were conducted in parallel for survey and in-depth assessment data. Analyses included descriptive statistics characterizing the two samples and Spearman correlations between initial-wave single-item risk factors and follow-up violent behavior (any violence, severe violence, other physical aggression) measured in the next year.

For both sampling frames, we employed multiple logistic regressions specifying five items representing risk factors as independent variables and violence outcomes as dependent variables. Scores from the single items were additively combined into a total score, which was also regressed onto violence outcomes for both sampling frames.

Regression analyses were used to derive receiver operating characteristic curves of sensitivities versus 1 minus specificities, with area under the curve providing an index of predictive validity. Predicted probabilities of severe violence in the next year were generated based on the total risk screen score at the initial wave.

Results

The characteristics of the national survey and in-depth assessment samples are summarized in

Table 1. Analyses showed that veterans in the in-depth assessments had a higher incidence of risk factors compared with survey participants, including financial problems (41% compared with 38%), witnessing others wounded (46% compared with 40%), PTSD (29% compared with 18%), alcohol misuse (31% compared with 24%), and history of violence or arrests (47% compared with 22%).

Spearman correlations (

Table 2) indicated statistically significant relationships (p<0.05) between initial-wave risk factors (financial instability, combat experience, alcohol misuse, violence or arrests, and probable PTSD plus anger) and violence. This pattern held for both levels of violence severity in both sampling frames, with few exceptions.

Multiple regression analyses for the survey (

Table 3) revealed that risk factors had significant associations (p<0.05) with outcome variables, suggesting that each risk factor contributed uniquely to the variance. The association of alcohol misuse with severe violence approached but fell short of significance. Summed total risk scores (as used in the screening tool) had significant associations with outcomes. Area-under-the-curve estimates in analyses for the survey ranged from 0.74 to 0.78.

Multiple regression analyses for the in-depth assessments (

Table 4) also showed that all risk factors except combat experience and alcohol misuse had significant associations (p<0.05) with outcome variables with respect to other physical aggression. As in the survey, total risk scores in the in-depth assessments had significant associations with outcomes. Area-under-the-curve estimates in analyses for the in-depth assessments ranged from 0.74 to 0.80.

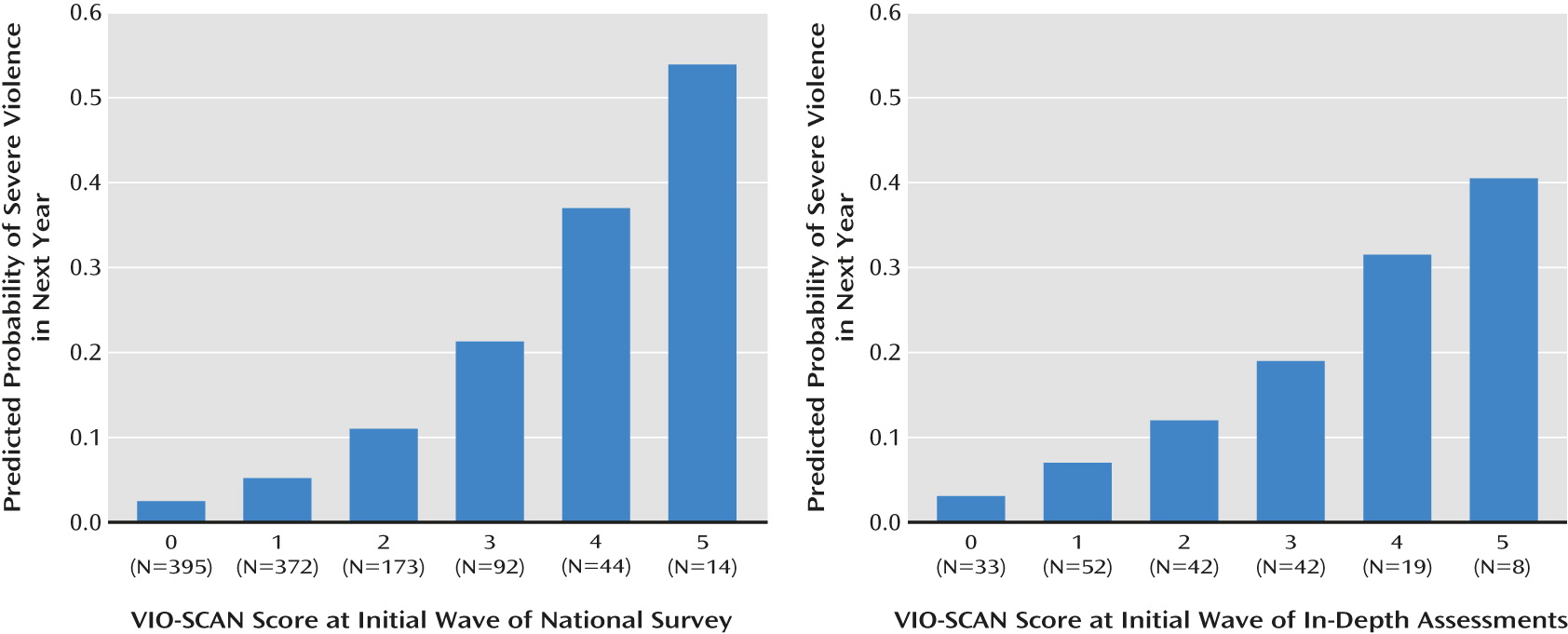

In

Figure 1, predicted probabilities of severe violence in the next year are presented as a function of risk screen score at the initial wave. In support of the screen’s predictive validity, incidents of violence markedly increase at higher levels of predicted risk. To illustrate, in the survey, a score of 5 suggests a predicted probability of severe violence in the next year of 0.539, whereas a score of 0 suggests a predicted probability of 0.025, translating into a 95.4% ([0.539–0.025]/0.539×100) lower odds of severe violence between scores of 5 and 0. Note that the vast majority of veterans had lower total scores, and only a small percentage (1.3%) had a score of 5.

Discussion

We report on the first evidence-based screen for risk of violence in military veterans, which we call the Violence Screening and Assessment of Needs (VIO-SCAN). The VIO-SCAN (

Figure 2) offers potentially improved clinical decision making and practice. First, it helps clinicians systematically gauge level of concern about a veteran's risk of violence. Second, the screen helps clinicians judge not just individual factors but a combination of factors, which should be taken into account in tandem when assessing violence risk in veterans. Third, the tool reduces stigma by demonstrating that PTSD alone does not automatically lead to high risk of violence in veterans: non-PTSD risk factors must be considered as well. Fourth, as several of the factors are dynamic (meeting basic needs, alcohol misuse, and probable PTSD plus anger), the VIO-SCAN can suggest interventions to reduce risk of violence in veterans. Fifth, the analyses show that risk factors used by clinicians when assessing risk in civilians (e.g., history of violence and arrests) are pertinent to assessing risk in veterans as well.

As a caution, clinicians should not equate this brief screen with a comprehensive risk assessment covering a host of risk and protective factors. Rather, the VIO-SCAN aims to identify candidates for a comprehensive risk assessment. Put differently, the VIO-SCAN is not an assessment of whether a veteran will or will not be violent, but rather a screen identifying whether a veteran may be at high risk and thereby require a full clinical workup to make a final risk judgment. Moreover, the screen will have false positives and false negatives; clinicians should understand that high scores will not always mean high risk of violence, and low scores do not always mean low risk of violence. Finally, clinicians should note that new research and scholarship indicate limits of violence risk tools (

43–

45) and caution against relying too heavily on results, particularly findings pointing to high risk.

Given its time frame, the VIO-SCAN is intended to screen for longer-term risk of violence, as opposed to acute risk. If clinicians are assessing need for immediate action or psychiatric hospitalization, it is critical to continue asking about current violent or homicidal ideation, intent, or plans. In these crisis situations, the screen can certainly help evaluate how serious a threat an individual poses in general; however, if a veteran endorses current homicidal ideation and plan but scores low on the VIO-SCAN, clinicians must recognize that the screen does not address imminent danger as typically defined by civil commitment statutes.

Conversely, the screen may identify veterans not currently at acute risk but who may have chronic risk. According to most civil commitment statutes, such individuals would not qualify for involuntary hospitalization. Instead, clinicians should recognize that outpatient veterans may benefit from specific risk management or safety plans to reduce the risk of future violence. Research has shown that social, psychological, and physical well-being are associated with significantly lower odds of violence in veterans, including those at higher risk (

6). Consequently, rehabilitation targeting these areas of functioning, as well as PTSD, anger, financial health, and alcohol misuse, may be indicated for veterans who score high on the VIO-SCAN.

Several psychometric limitations of the research should also be mentioned. Regarding external validity, although the VIO-SCAN was not based on veterans from previous eras of service, risk factors were selected from the scientific literature on such veterans (

7–

11). Therefore, although research is needed to replicate these findings in other samples, VIO-SCAN content is derived from the broader veteran population and is arguably relevant to all veterans. Prospective research is needed to evaluate the predictive validity of this screening tool for violence and other outcomes (e.g., suicidality) in veterans. For example, studying clinicians' use of the VIO-SCAN in VA and non-VA practice settings would be valuable.

Regarding internal validity, given that much of the data were obtained by self-report, underreporting is possible; however, the rates of risk factors (e.g., PTSD, alcohol misuse) and violence in our data generally comport with existing research on veterans (

3,

4,

29,

46,

47). It was not possible to obtain criminal records, which might have revealed additional violence. However, studies have shown that self-report and collateral reports cover most violent incidents in civilians (

41) and that veterans’ self-reported violence is related to arrest records for violent crimes (

1,

26).

Violence was measured, rather than risk level on comprehensive risk assessment tools, because we needed to test basic assumptions, such as whether more risk factors related to greater incidence of violence or whether the overall model was associated with violence. Our reporting area-under-the-curve estimates on predictive validity was for statistical purposes only, and we do not intend for clinicians to treat the VIO-SCAN as if it represented a mathematical or actuarial algorithm to use in practice. Clinicians should not use the screen to predict violence per se, but rather to determine whether a veteran needs a full workup to ascertain level of risk more definitively.

It is also important for clinicians using the VIO-SCAN to balance potentially competing values when assessing risk of violence. On the one hand, because violence is a documented problem for a subset of veterans, it is important for the safety of veterans, their families, and the public that clinicians not miss veterans who urgently need help. On the other hand, the clinical process of assessing violence runs the risk of potentially mislabeling and stigmatizing individuals as “high risk” or “violent.” The VIO-SCAN should never be used to label a veteran or be used alone as a comprehensive risk assessment. Instead, it should be used to provide a structured and empirically supported method to screen veterans for potential problems with violence and to prioritize which veterans need a full clinical workup.

The VIO-SCAN should also be used to assess needs and explore treatment options for reducing violence in veterans. One model that may be instructive is the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality framework, which is useful in suicide prevention in both civilian (

48) and military samples (

49). In this approach, the primary methods of treatment engagement, assessment, treatment planning, progress tracking, and outcome evaluation are all conducted using evidence-based tools that increase the likelihood that clinicians will ask about important but often missed risk factors. Similar approaches may fruitfully apply to violence risk in veterans. Within such a framework, violence risk management not only would include ongoing, evidence-based risk assessment, but also would also give veterans opportunities to learn about and assess their own triggers (

6).