A middle-aged woman with obsessive-compulsive symptoms with atypical features is seen for a diagnostic neuropsychiatric assessment.

“Ms. A,” a 46-year-old woman, was referred for inpatient treatment at the Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Institute (OCDI) of McLean Hospital (Belmont, Mass.). She had no prior history of psychiatric disorders. Two years earlier she had developed cleaning and checking rituals that gradually became severe and intrusive to the point of losing her long-term employment. She had been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) by a community psychiatrist. Sertraline was prescribed, but she soon stopped taking it because of side effects. After a few days at the OCDI, a diagnostic neuropsychiatric assessment was requested because of atypical features for OCD, including a late age at onset and an inability to engage in therapy.

Ms. A denied obsessions or anxiety. She felt well and had no concerns about having lost her job. Collateral history was obtained from her husband. After the onset of compulsions, he noticed major changes in her personality. Ms. A had previously been caring, organized, and reliable, but over the past 2 years she had become emotionally detached and apathetic, and she now had poor judgment and neglected her daughter. She also exhibited odd eating behaviors, such as eating butter by the spoonful. Most recently she had developed bilateral hand-rubbing stereotypies. There was no family history of psychiatric disorders, dementia, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

On examination, the patient was superficially cooperative, but without insight, awareness, or concern about her behavior. Her affect was jovial and shallow. She was indifferent to her family’s concerns. There were no psychotic symptoms or language abnormalities. Her score on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment was 25/30 (3/5 in the visuospatial and executive tasks, 4/5 on the serial 7s task, 3/5 on the recall task, +2 words with cues), and her score on the Frontal Assessment Battery was 17/18. On phonemic fluency testing, she listed 12 words, reciting more words in the first 15 seconds than in the last 45 seconds (generation deficit). A brief social cognition battery was administered. She made no mistakes on faux-pas vignettes, but identified only 17/36 emotions on the Reading the Mind in the Eyes test. Her elemental neurological examination was normal except for inextinguishable bilateral palmomental reflexes.

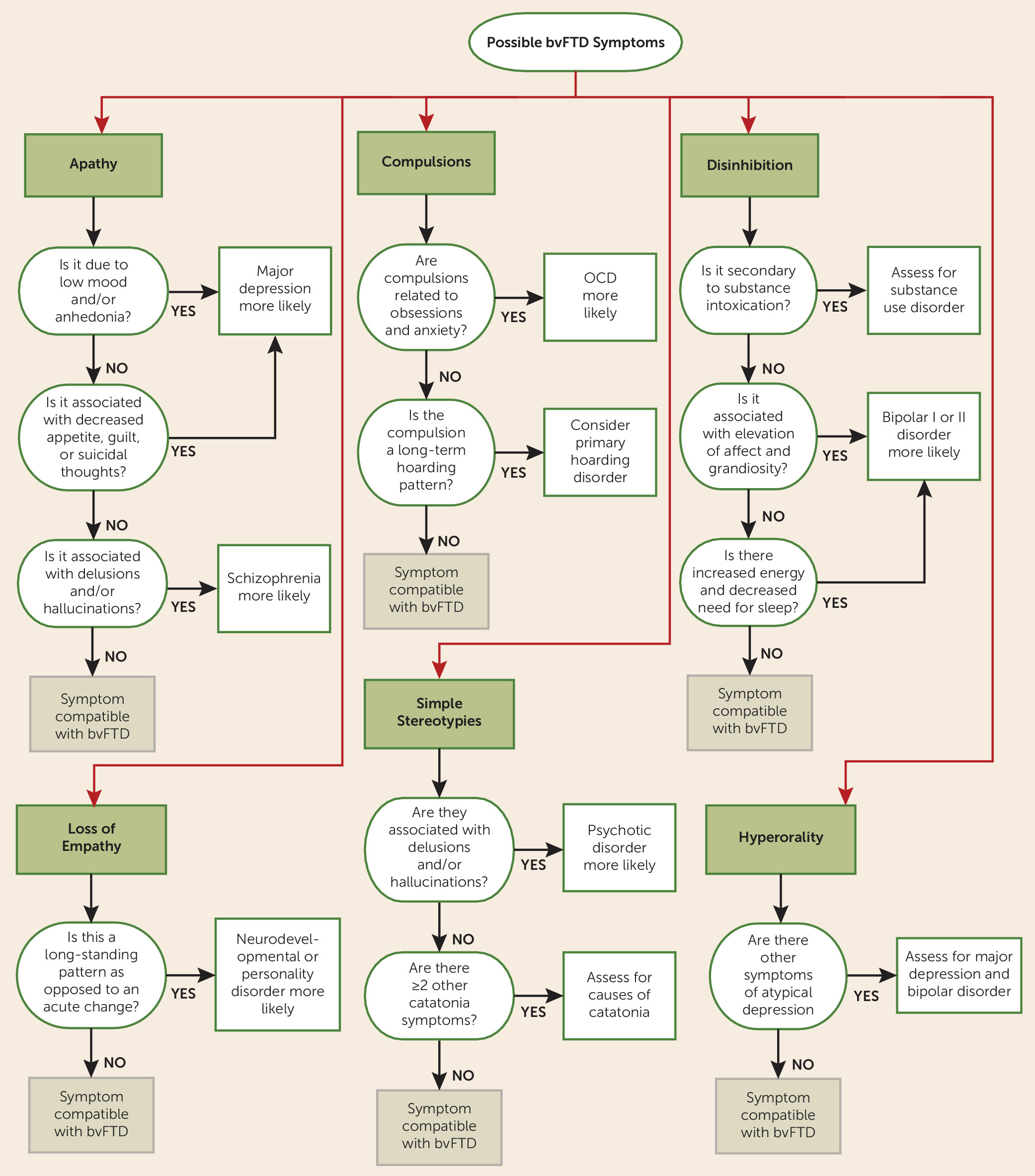

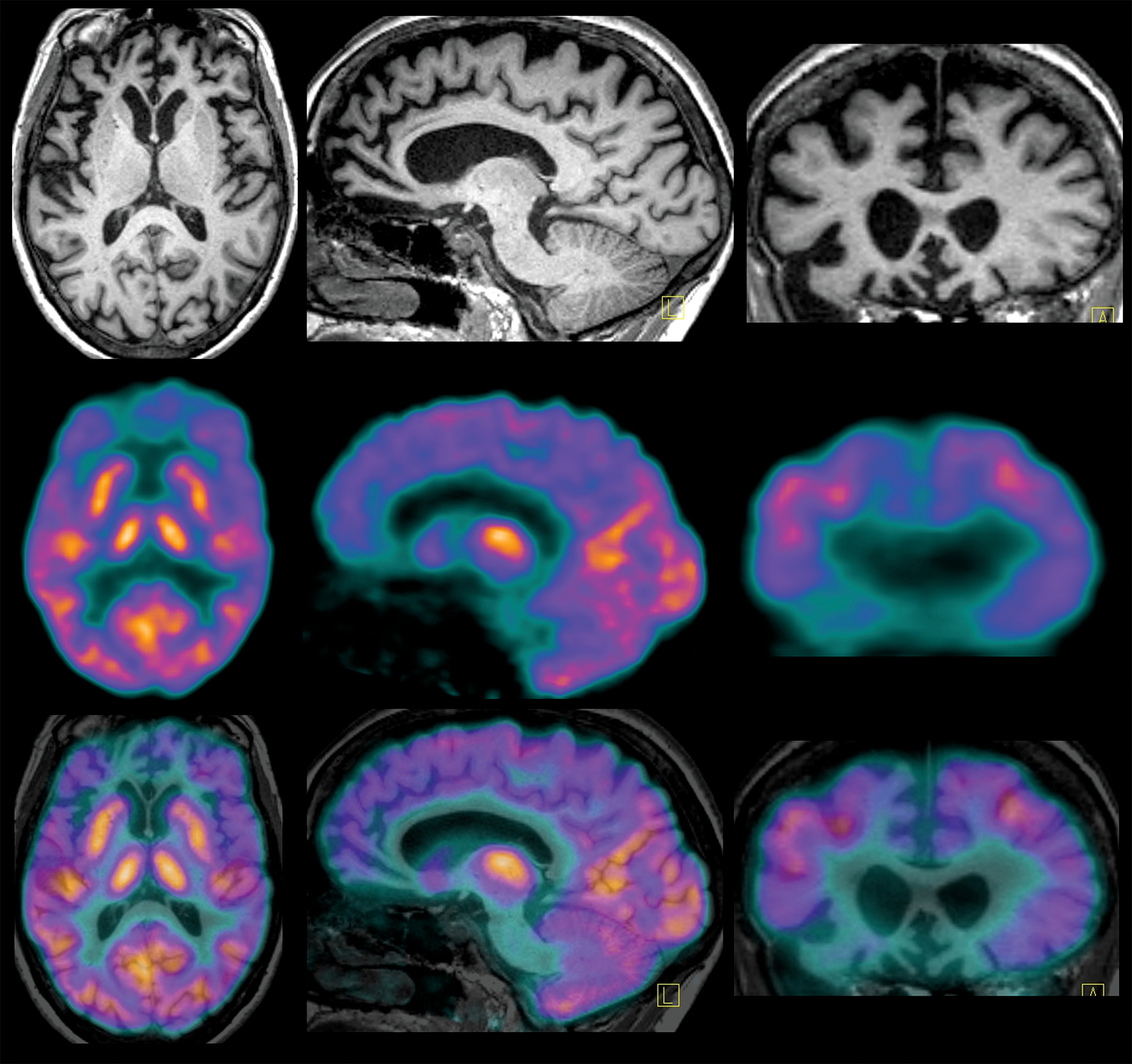

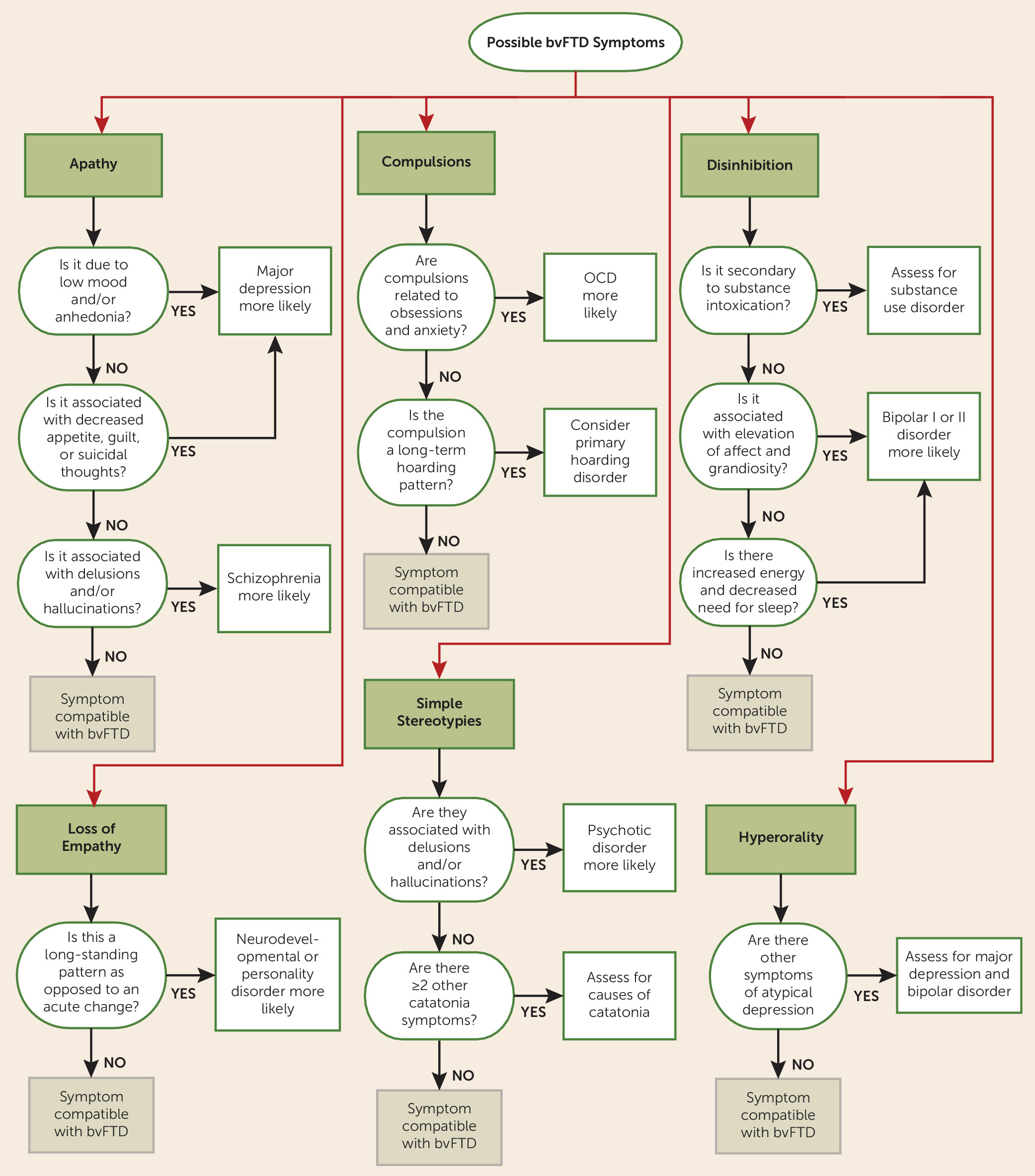

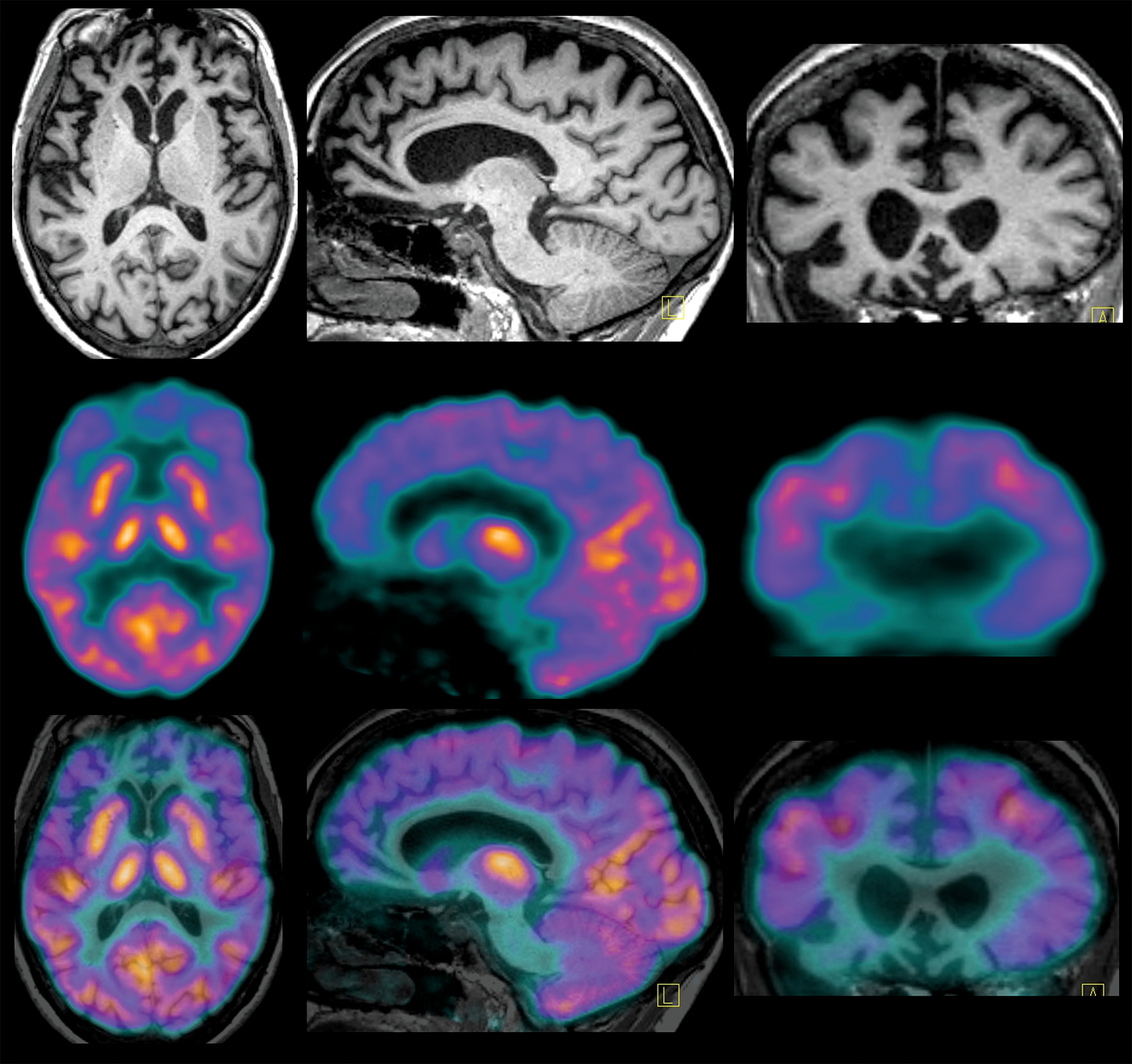

While Ms. A’s compulsions were typical of OCD, the clinical profile was not compatible with this diagnosis because of the absence of anxiety or distress related to the rituals. Given the history of loss of empathy, apathy, careless actions, dietary changes, hand-rubbing stereotypies, generation deficits, and impaired facial emotion recognition, she met clinical criteria for possible behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). A recent brain MRI performed at a private facility was reported as normal (images were not available for review). However, another brain MRI, at our hospital, showed moderate to severe circumscribed ventromedial prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortical atrophy bilaterally. A [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography study demonstrated marked cortical hypometabolism within the medial aspects of the anterior frontal lobes. Hematology, biochemistry, and EEG results were within normal limits. The final diagnosis was probable bvFTD. A genetic evaluation revealed none of the autosomal dominant mutations associated with frontotemporal dementia (C9ORF72, progranulin, and MAPT).

Over the next few months, aggressive behaviors at home became more prominent. Divalproex sodium was initiated for behavioral management. Despite the medication, Ms. A’s behavior continued to deteriorate, and she was admitted to a psychiatric ward after biting her daughter. She was placed in an assisted-living facility 30 months after the onset of symptoms.