Diagnosing ADHD in adults draws much of its legitimacy from the assumption that it is the same disorder as childhood ADHD, with the same neurodevelopmental etiology, affecting the same individuals from childhood to adulthood. DSM-5 places adult ADHD alongside childhood ADHD in the category of neurodevelopmental disorders, and states, “ADHD begins in childhood” (p. 61). Consensus statements recommend treating adult ADHD on the grounds that it is a continuation from childhood ADHD (

1,

54). However, to our knowledge the dual assumptions that adult ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder and begins in childhood remain untested by a prospective longitudinal study of the childhoods of adults with ADHD.

A test is lacking because developmental research on adult ADHD has been limited to two designs, each with a shortcoming that limits inference about childhood origins of adult ADHD (

2). Studies with the first design have followed up children with ADHD who were referred, diagnosed, and treated years ago (

3–

6). This design offers the advantage of prospective childhood data. However, clinical samples have the disadvantage of initial referral biases that limit inference about adult outcomes (

7–

10). Moreover, follow-ups of clinical childhood ADHD samples have not yielded many participants who meet adult ADHD criteria (

3–

6). Studies with the second design have surveyed adult ADHD in community samples (

11–

14). This design offers the advantage of substantial numbers of adult ADHD cases, unbiased by treatment seeking, as well as comparison subjects who represent the non-ADHD population. However, these studies have the disadvantage of having to rely on participants’ retrospective recall for assessing childhood onset and preadult etiological factors. Retrospective recall entails sources of invalidity that limit inference about the developmental origins of the adult disorder (

15–

17).

Results

Prevalence and Continuity

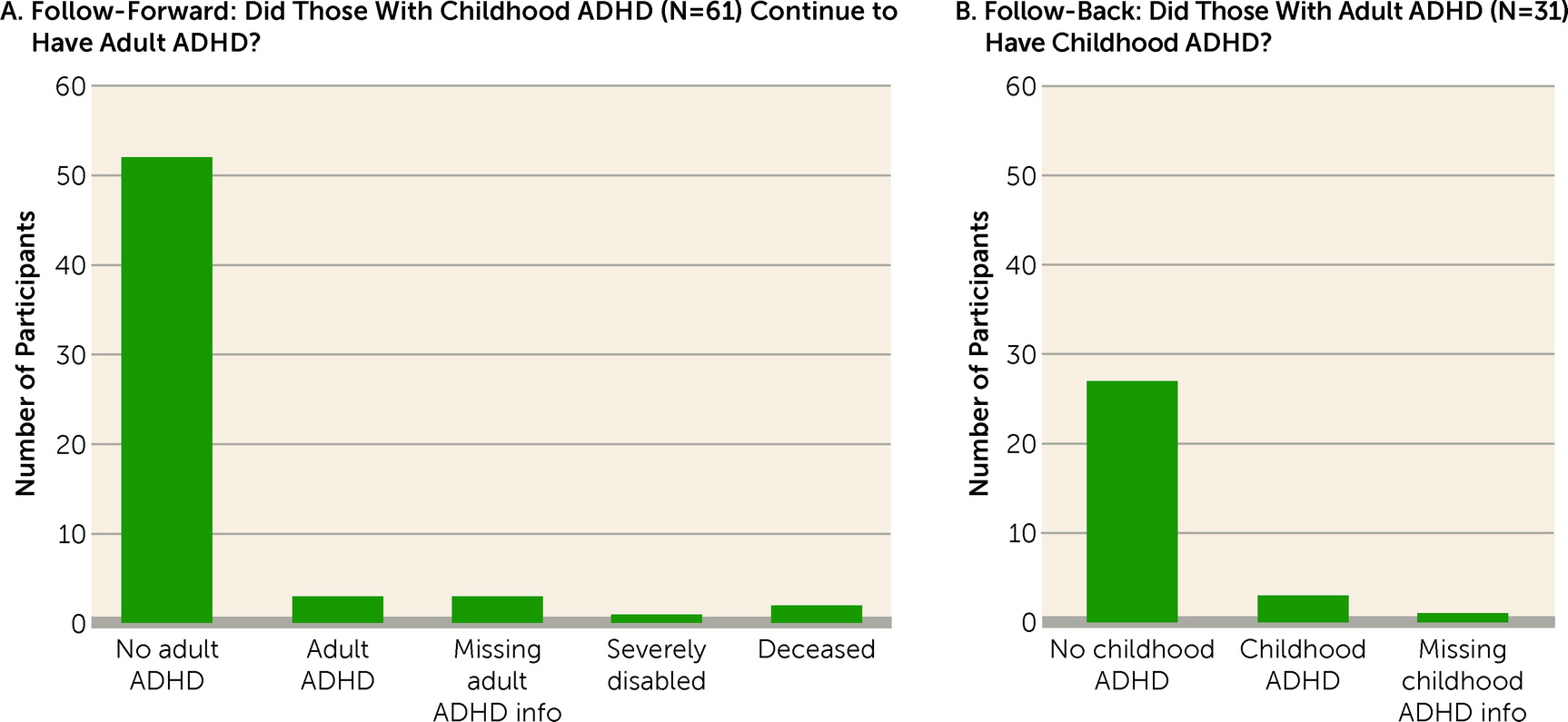

The cohort prevalence of ADHD was 6% in childhood and 3% at age 38 (

Table 1), which correspond to previous estimates among children (

31–

33) and adults (

34,

35). Unexpectedly, childhood and adult diagnoses comprised virtually nonoverlapping sets of individuals (

Figure 1). Follow-forward from childhood ADHD to adult ADHD revealed that only three (5%) of the cohort’s 61 childhood cases still met diagnostic criteria at age 38. Follow-back showed that these three individuals constituted only 10% of the cohort’s 31 ADHD cases at age 38. (These three individuals were retained in both the child ADHD and adult ADHD groups for subsequent analyses.) We also found that it was not the case that many childhood ADHD cases’ adult symptom levels fell just below the five-symptom adult diagnostic threshold (

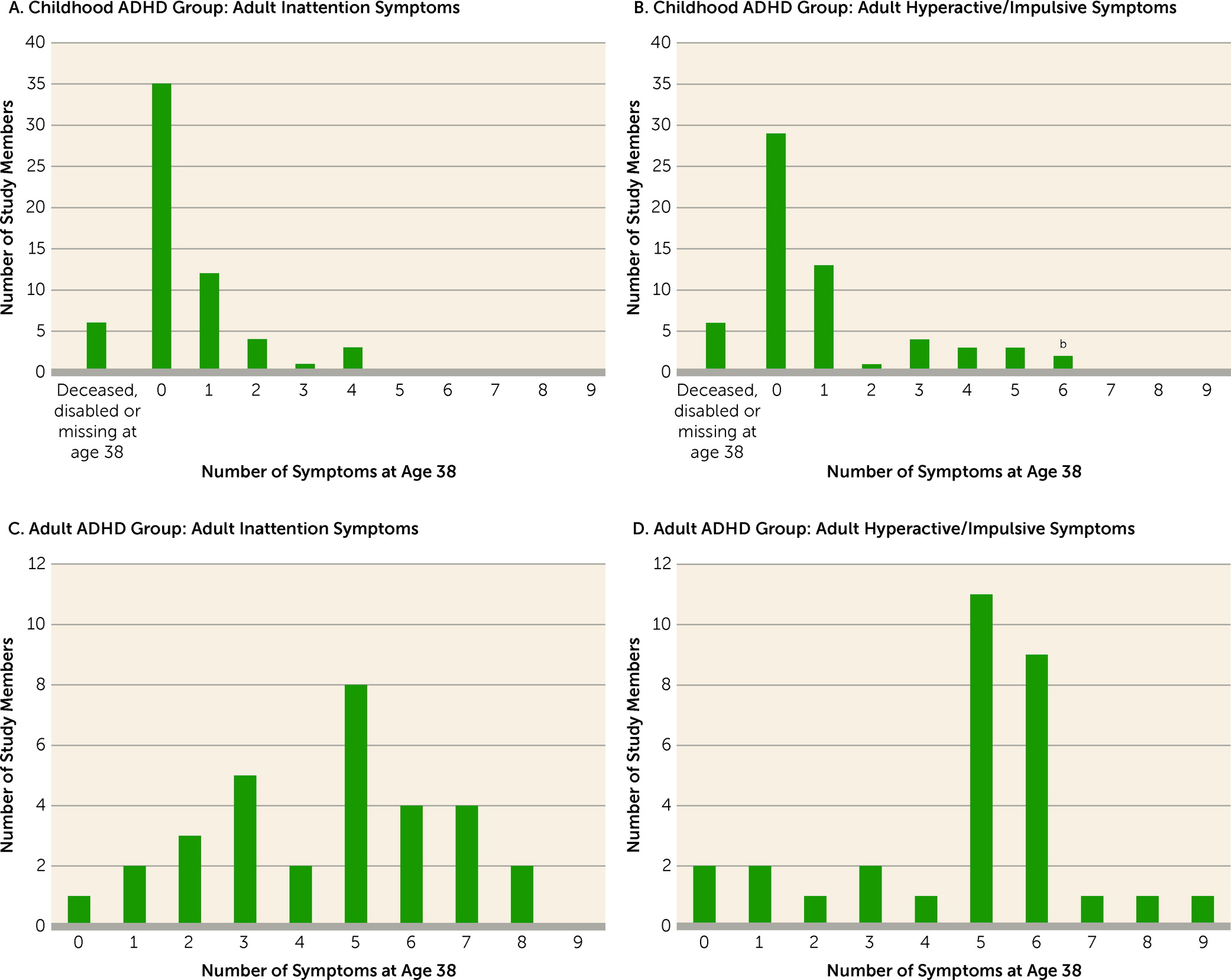

Figure 2).

Sex Distribution

Childhood ADHD cases were predominantly male (see

Table 1). Among adult ADHD cases, there was no significant sex difference. All subsequent significance tests included sex as a covariate.

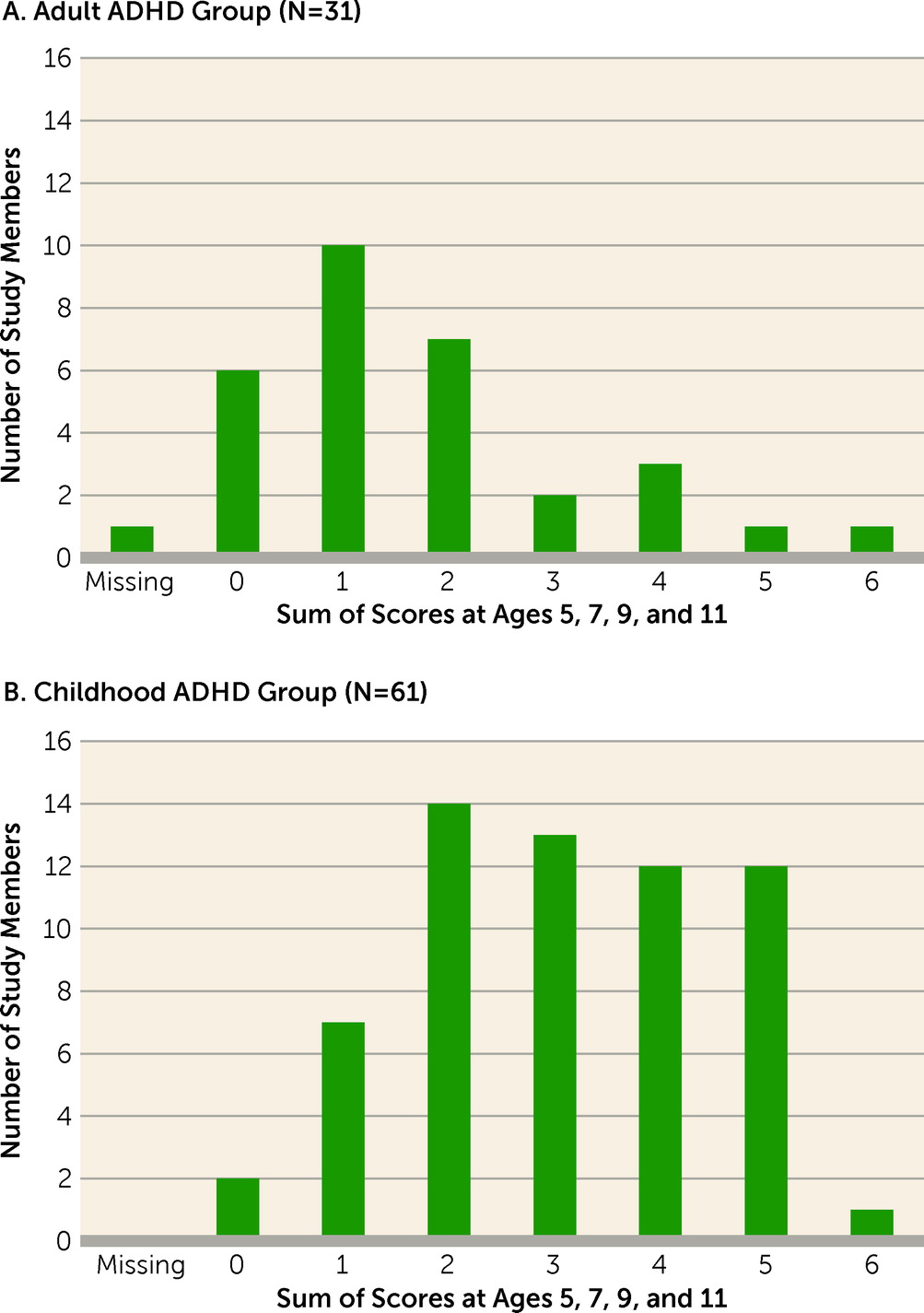

Prospective Onset Before Age 12

Averaged parent/teacher reports from ages 5, 7, 9, and 11 documented markedly elevated symptoms before age 12 (as required by DSM-5) for the childhood ADHD group (effect size=1.60 SD) but only mildly elevated symptoms for the adult ADHD group (effect size=0.33 SD). For example, few adult ADHD cases had at least one symptom that had been rated “2=certainly” by their elementary school teachers, whereas most childhood ADHD cases had more than one symptom with this rating (

Figure 3).

Cross-Setting Confirmation in Childhood

As expected, the childhood ADHD group’s mean symptom scores were markedly elevated according to parents (effect size=1.18 SD) and teachers (effect size=1.82 SD) at the time of diagnosis (ages 11, 13, and 15) (see

Table 1). In contrast, the adult ADHD group’s mean symptom scores did not differ from those of comparison subjects according to parents (effect size=0.09 SD) and were only modestly elevated according to teachers (effect size=0.31 SD).

Cross-Setting Confirmation in Adulthood

At age 38, symptom checklists were mailed to informants who knew the participant well. According to informants, as adults the childhood ADHD group had significantly elevated symptoms of inattention (effect size=0.87 SD) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (effect size=0.81 SD) (see

Table 1). Informants also reported elevated symptoms for the adult ADHD group (inattention, effect size=0.90 SD; hyperactivity/impulsivity, effect size=0.74 SD).

Retrospective Parental Recall of Onset Before Age 12

Many adult patients rely on their parents’ memories of childhood symptom onset. Among childhood ADHD cases, only 23% had parents who recalled that their child had core ADHD symptoms or was diagnosed with ADHD (see

Table 1). Thus, 77% of documented childhood ADHD cases were forgotten 20 years later. Also, the parents of 35 comparison subjects (4%) recalled evidence that their child had ADHD.

Self-Perceived ADHD-Associated Adult Impairment

At age 38, using a 5-point interference scale, former ADHD children reported that ADHD symptoms were impairing their adult work and family lives, a significant albeit modest difference from the comparison group (effect size=0.29 SD) (see

Table 1). They were also significantly less satisfied with life than were comparison subjects. However, the childhood ADHD group denied having problems such as being disorganized, underachieving, being exhausting or draining to others, having accidents from overdoing it, and risky driving.

The impairment story was worse for adults with ADHD. They reported markedly elevated impairment as a result of ADHD-associated problems (effect size=2.26 SD), felt less satisfied with their lives, and reported problems stemming from being disorganized, underachieving, exhausting or draining to others, having accidents from overdoing it, and risky driving.

ADHD Medication

This cohort was unmedicated for ADHD during childhood, as prescribing medication for ADHD was rare in New Zealand in the 1970s and 1980s. Use of medication has remained rare in the treatment of adults with ADHD in New Zealand. ADHD medication (methylphenidate,

d-amphetamine, atomoxetine) was ever used during adulthood by only five persons (see

Table 1): one comparison subject with illicit methylphenidate use and four adult ADHD participants, of whom one also had childhood ADHD. (Only one childhood ADHD and two adult ADHD cases took ADHD medication at the time of the age 38 assessment.)

Mental Health in Childhood

As expected, the childhood ADHD group had significantly elevated rates of conduct disorder, depression, and anxiety as children (

Table 2). Although the adult ADHD group shared a childhood history of conduct disorder, this link was more prominent among childhood ADHD cases (59%) than among adult ADHD cases (31%).

Mental Health in Adulthood

Neither the childhood ADHD nor the adult ADHD group had significantly elevated rates of mania, depression, or anxiety disorders as adults (see

Table 2). The adult ADHD group had significantly elevated rates of persistently diagnosed dependence on alcohol, cannabis, or other drugs (48.4%) and persistent tobacco dependence (38.7%). Among adults with ADHD, a significant 70% reported contact between ages 21 and 38 with a professional for a mental health problem (a general practitioner, a psychologist, or a psychiatrist, including for addiction treatment) and 48.4% of them had taken medication for a problem other than ADHD, in the following order: depression, anxiety, psychological trauma, substance treatment, and eating disorder.

Cognitive Assessments in Childhood

As expected, the childhood ADHD group showed significant cognitive deficits as children (

Table 3). As a group, they scored 0.55 standard deviations below the norm on our composite measure of brain integrity at age 3. As school-age children, their mean IQ score was 10 points below the norm. They exhibited deficits in reading achievement, on the Trail Making Test, part B (a commonly used test of executive control), and on verbal learning–delayed recall. In comparison, the adult ADHD group had evidenced no significant tested cognitive deficits as children, apart from mild reading delay.

Cognitive Assessments in Adulthood

Although participants with childhood ADHD may have outgrown their ADHD diagnosis, they did not outgrow their cognitive difficulties. At age 38, their mean IQ remained 10 points below the norm (see

Table 3). The childhood ADHD group also showed a deficit on the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) rapid visual processing “continuous performance test”; they scored under par for attentional vigilance and made more false-alarm errors from jumping to respond too soon. They still had significant deficits on the Trail Making Test, part B, and on verbal learning recall. Despite these tested deficits, participants with childhood ADHD self-reported only mildly elevated cognitive complaints in adulthood (effect size=0.14 SD).

In comparison, participants with adult ADHD had relatively few tested cognitive deficits as adults, apart from scoring significantly below comparison subjects on perceptual reasoning and having more false alarms on the rapid visual processing test. Despite their lack of tested deficits in childhood and relatively mild tested deficits in adulthood, our adults with ADHD reported many subjective cognitive complaints, scoring 1.62 standard deviations above the norm (and 1.48 standard deviations worse than the childhood ADHD group).

Polygenic Risk

A genome-wide polygenic risk score derived from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of childhood ADHD was significantly elevated in the childhood ADHD group, but not in the adult ADHD group (see

Table 3).

Life Functioning in Adulthood

Relative to the comparison group, a significantly smaller percentage of the childhood ADHD group completed a university degree, and they reported significantly lower incomes, somewhat fewer saving behaviors, and more troubles with debt and cash flow (

Table 4). Administrative records revealed that the childhood ADHD group had significantly lower credit ratings, longer duration of social welfare benefit receipt, more injury-related insurance claims, and more criminal convictions.

Although the adult ADHD group did not differ significantly from the comparison group on university education or income, they reported significantly fewer saving behaviors and more troubles with debt and cash flow. Administrative records revealed that the adult ADHD group also had significantly lower credit ratings, longer duration of social welfare benefit receipt, and more injury-related insurance claims than the comparison group. The criminal conviction rate was elevated but was not significantly different from the rate for comparison subjects.

Discussion

In 2013, DSM-5 newly formalized the criteria for diagnosing ADHD in adults. DSM-5, clinicians, and the public presume that adult ADHD is the same childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorder as childhood ADHD, but is it? To answer this question, we described in parallel the life course of individuals who met criteria for the familiar diagnosis of childhood ADHD and individuals who met criteria for the newer diagnosis of adult ADHD. Like previous follow-ups of individuals with childhood ADHD, we found that individuals with childhood ADHD tended to outgrow the full ADHD diagnosis but continued to experience difficulties in life adjustment into their 30s. Like previous surveys of adults with ADHD, we found that these adults showed ample evidence of impairment warranting clinical intervention. However, our follow-back revealed that, in this cohort, the adult syndrome did not represent a continuation from a childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorder. To our knowledge, this is the first follow-back prospective study of the childhood origins of individuals diagnosed with DSM-5 adult ADHD; thus, our novel finding must be evaluated in future studies.

Our study offered certain design advantages. Our four-decade study supported both follow-forward and follow-back analyses of a representative birth cohort, in which ADHD cases were ascertained without bias by referral or treatment. Participants’ self-reports could be supplemented by independent sources: parents, teachers, informants, formal cognitive testing, and administrative records.

This study also has limitations. First, as the findings were not hypothesized in advance, replication in other cohorts is imperative. Second, childhood ADHD was diagnosed using the edition of DSM that was current at the time, which was DSM-III. Third, because ADHD was deemed a childhood-only disorder in DSM-III-R, our study did not assess ADHD during the participants’ 20s. Thus, we were unable to trace the decline in symptoms for childhood cases or the emergence of symptoms for adult cases. Fourth, our adult ADHD group was small, which limited statistical power and our ability to examine heterogeneity within this group. However, the nonsignificant effect sizes were very small, suggesting that lack of power was not the reason for the lack of significant differences. Fifth, personality disorder was not ascertained. Sixth, we lacked neuroimaging data to test the neurodevelopmental hypothesis, but to our knowledge, no multidecade longitudinal neuroimaging study of a population-representative cohort is available. Finally, the fact that our cohort’s ADHD cases were unbiased by clinical referral and largely untreated with ADHD medications is an advantage for studying the natural history of ADHD, but it may be a disadvantage for clinicians needing an evidence base that generalizes to patients in treatment.

The Childhood ADHD Group

The Dunedin cohort’s childhood ADHD cases conformed to expectations derived from past research on childhood ADHD (

30). This conformity allays concerns about the use of this cohort for researching ADHD. The prevalence was 6%, and most were boys. Participants with childhood ADHD had the expected comorbid conditions, particularly conduct and anxiety disorders. They showed elevated polygenic risks identified in previous childhood ADHD GWAS. They exhibited neurocognitive dysfunctions as early as age 3, and they had poor cognitive test performance, consistent with the conceptualization of ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder (

36,

37).

As 38-year-old adults, the former ADHD children also conformed to expectations derived from previous studies that have followed ADHD children to adulthood (

5,

18). All but three of them no longer met full diagnostic criteria for ADHD. This is consistent with results of a meta-analysis (

38) reporting that only 16% of childhood ADHD cases continue to meet diagnostic criteria into their 20s, and this percentage continues declining thereafter. It was not the case that the group had symptoms just below the adult diagnostic threshold. Despite having shed their childhood diagnoses, they retained the neuropsychological deficits that signify ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder. Consistent with these deficits, few had managed to obtain a university degree, and they were struggling financially. Many had experienced posttraumatic stress disorder, a suicide attempt, injury-related insurance claims, or adult criminal convictions. This former ADHD group rated ADHD symptoms as still exerting a mildly impairing effect on their adult lives.

The Adult ADHD Group

The Dunedin cohort’s adult ADHD cases met DSM-5 diagnostic criterion A—five or more symptoms of inattention or of hyperactivity/impulsivity—in our interview. The group met criterion C—symptoms in two or more settings—by informant reports of elevated symptoms. The group met criterion D—interference with activities—as they reported markedly elevated life impairment.

We did not ask participants about criterion B, onset before age 12, because retrospective recall of psychiatric symptoms across decades has poor validity and yields false negative reports of childhood-onset hyperactivity (

39–

41). Consistent with this, in parent interviews when our study members were in their 30s, the parents of 78% of the participants with childhood ADHD had forgotten their child’s ADHD onset before age 12 (despite having reported the child’s symptoms at ages 5, 7, 9, and 11). Retrospective recall also yields false positives; the parents of 35 comparison subjects recalled their child having childhood ADHD. Considering this invalidity, an alternative is to require prospective evidence of pre-age-12 symptoms (see

Figure 3); doing so would yield a near-zero prevalence of adult ADHD meeting full DSM-5 criteria (0.03%). We suspect that, like us, clinicians often ignore the childhood-onset criterion for adult patients needing treatment.

With DSM-5 diagnoses made on the basis of symptoms, we obtained a prevalence rate of about 3% and a near-equal sex balance, matching previous cross-sectional surveys of adult ADHD. However, contrary to our expectations, we did not find evidence that adult ADHD so defined is a childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorder. Our first hint was the elevated prevalence in women, which has been reported before and differs from childhood ADHD. Second, when we exploited our study’s prospective design, we found evidence that almost none of the participants with adult ADHD had ADHD as children. Moreover, as a group, those with adult ADHD did not have symptoms just below the threshold at the time of childhood diagnosis; according to their parents’ reports, their mean symptom score was normative then. Although teacher symptom ratings were mildly elevated, the elevation represented a level far below the threshold for diagnosis.

Third, and most surprising, as a group, participants with adult ADHD lacked the childhood neuropsychological deficits that are the signature of ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder. For example, their mean WISC-R IQ was only 2 points below the population norm of 100. When retested at age 38, their mean WAIS-IV IQ was 3 points below the norm. They did not differ significantly from comparison subjects on the WAIS-IV working memory index or a continuous-performance test of attentional vigilance, which are generally considered cardinal deficits in individuals with ADHD (

42). Meta-analyses have reported wider cognitive differences between adults with ADHD and comparison subjects (

43,

44), but it should be remembered that studies in these meta-analyses were biased toward finding larger differences because they compared clinical ADHD patients with non-ADHD comparison subjects who did not represent the range of cognitive abilities in the non-ADHD population (

44,

45). Despite lacking tested neuropsychological deficits, the adult ADHD group reported elevated cognitive complaints in our interview—for example, that they forget what they came to the shop to buy, cannot think when the TV or radio is on, or have word-finding difficulty. This discrepancy between test scores and subjective complaints has been reported in adult ADHD before and is not yet understood (

46,

47).

Treatment Need

Our data suggest the possibility that adult ADHD may not be the same disorder as childhood ADHD. Does this imply that adults presenting with the ADHD symptom picture do not need treatment? Unequivocally no. Life interference that warrants treatment was independently confirmed by official records of injury-related insurance claims and low credit ratings. Treatment need was also indicated by the adults’ self-reports that their lives tend to be marred by dissatisfaction, everyday cognitive problems, and troubles with debt, cash flow, and inadequate saving behaviors, and they tended to believe that they waste time because of being disorganized, have failed to fulfill their potential, are exhausting or draining to others, have accidents from overdoing it, and take risks while driving by tailgating and speeding. Interestingly, 70% of these adults reported mental health treatment contact during their 20s and 30s. As such, they were getting professional attention, but not the treatment of choice for ADHD; only 13% had been treated with methylphenidate or atomoxetine. To be fair to their physicians, applying the ADHD diagnosis to adults was only highlighted by DSM-5 in 2013, after we made our diagnoses. In any case, we found ample evidence of treatment need and treatment contact.

Diagnostic Possibilities

The remaining question is, if these impaired adults do not have the neurodevelopmental disorder of ADHD, what do they have? At 38, this cohort is too young for prodromal dementia. The possibility of malingering has been raised (

48,

49), but this can be discarded, as Dunedin Study members lack any motive to fabricate their reports to us.

A second possibility is that they should not have been diagnosed with ADHD because their symptoms and impairment might be better explained by another disorder (exclusionary criterion E). Although they did not have elevated rates of depression or anxiety from ages 21 to 38, we know that as adults nearly half of them had persistent substance dependence, as diagnosed on multiple occasions by the Study. It is tempting to conclude that adult ADHD is secondary to substance abuse. Unfortunately, our data cannot resolve the question of whether substance abuse led to ADHD symptoms or whether adult ADHD symptoms antedated substance abuse. Disentangling which symptoms are primary and secondary is likewise difficult in clinical practice. Ubiquitous comorbidity for adults with ADHD has been reported before (

12), suggesting the hypothesis that ADHD symptoms in adults in their 30s might be the psychiatric equivalent of fever, a syndrome that accompanies many different illnesses and is diagnostically nonspecific but signals treatment need. However, 55% of our participants with adult ADHD had no other concurrent diagnosis at age 38; the ADHD symptom picture can present alone in adults.

A third intriguing possibility is that adult ADHD is a bona fide disorder that has unfortunately been mistaken for the neurodevelopmental disorder of ADHD because of surface similarities, and given the wrong name. This possibility would illustrate an oft-bemoaned disadvantage of a diagnostic system based on symptoms alone without recourse to etiological information: overreliance on face validity. We found little evidence that ADHD in adults had a childhood onset. Interestingly, there is strong scientific consensus that it is extremely difficult to document childhood onset in adults with ADHD (

3,

50,

51). The frequent interpretation has been that childhood-onset ADHD was there but patients do not remember it. Our finding suggests the contrary hypothesis that there is an adult-onset form of ADHD. If this hypothesis is supported by research, then adult ADHD’s place in DSM (and its diagnostic criteria) may need reconsideration. Ironically, by requiring childhood onset and neurodevelopmental origins, DSM-5 leaves these impaired adults out of the classification system. We found little evidence that neuropsychological dysfunction is the core etiological feature of DSM-5 adult ADHD. Other research has uncovered different etiological factors for childhood and adult ADHD, including heritability differences (

52,

53). Likewise, we found that childhood ADHD-associated polygenic risk did not characterize adult ADHD. Unfortunately, the assumption that adult ADHD is the same as childhood ADHD and therefore that its causes have already been researched may be discouraging etiological research into adult ADHD. If our finding of no childhood-onset neurodevelopmental abnormality for the majority of adult ADHD cases is confirmed by others, then the etiology for adults with an ADHD syndrome will need to be found.