Lewy body dementia is a common cause of degenerative dementia in older people, accounting for some 3%–15% of cases (

1,

2). It is characterized by impairments and fluctuations in cognition, recurrent visual hallucinations, and motor features of parkinsonism. Other significant features include sleep disorders, depression, delusions, and autonomic dysfunction (

3,

4). The term “Lewy body dementia” is used here to include two related disorders: dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD). Comparisons suggest a broad overlap clinically, although executive impairment, delusions, and hallucinations may be more common in DLB (

5,

6). The diagnosis of PDD is applied when motor symptoms occur at least 1 year before dementia, and the diagnosis of DLB is applied when dementia precedes or is closely followed by motor symptoms (

4).

To develop effective approaches to care, it is necessary to establish which strategies are effective and to determine whether DLB and PDD are amenable to the same treatments. In this article, we review pharmacological management strategies and address three questions: What are their benefits, harms, and costs in the disorders? What views do patients and caregivers have of these strategies? How, when, and where should these strategies be implemented?

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review of pharmacological strategies for Lewy body dementia, identifying 28,568 potentially relevant papers. Forty-four papers examining 22 pharmacological strategies were included in our analyses. High-level evidence was rare, with only 17 randomized controlled trials. Methodological quality was rated as weak for 41% of included studies, moderate for 39%, and strong for 20%.

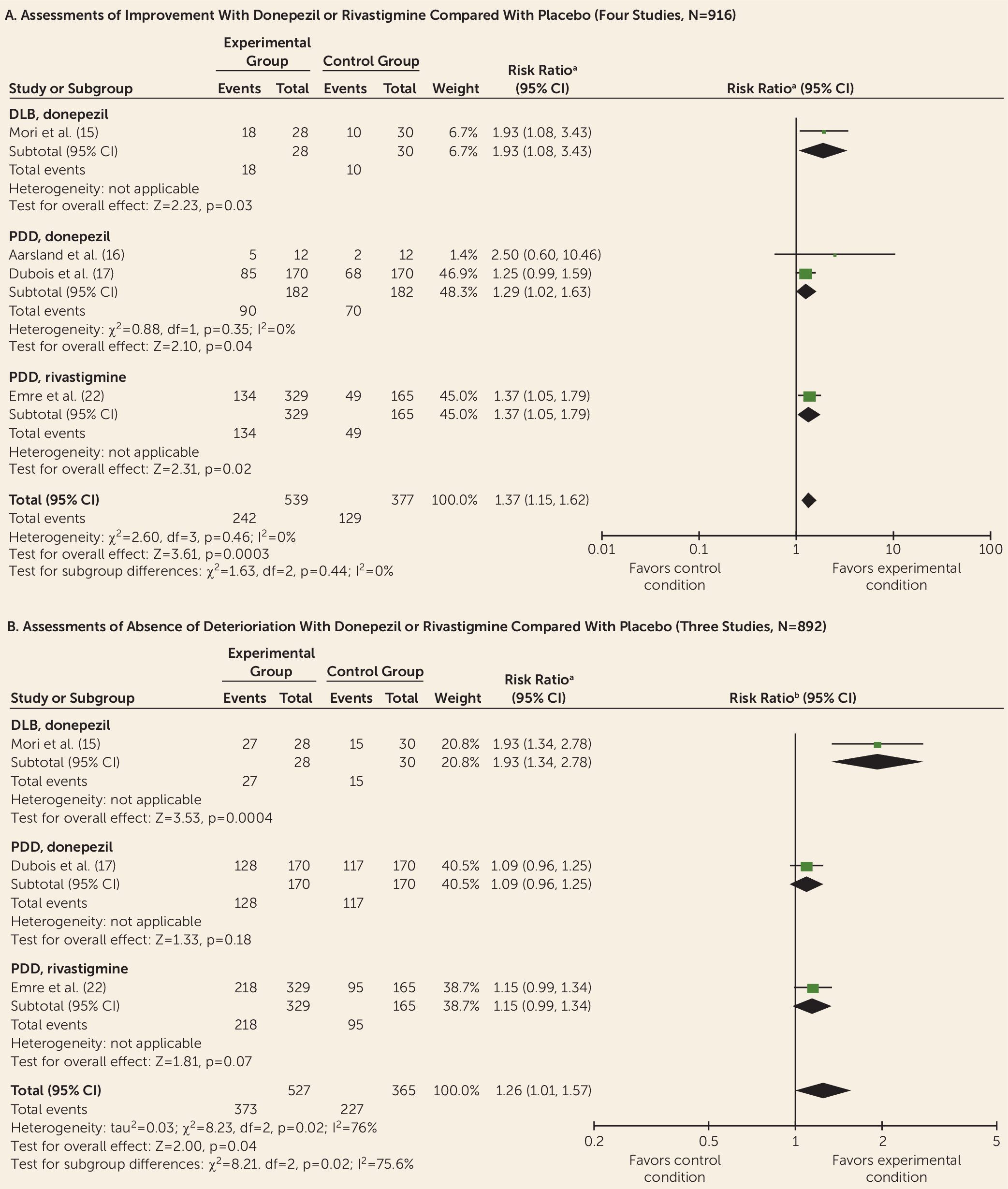

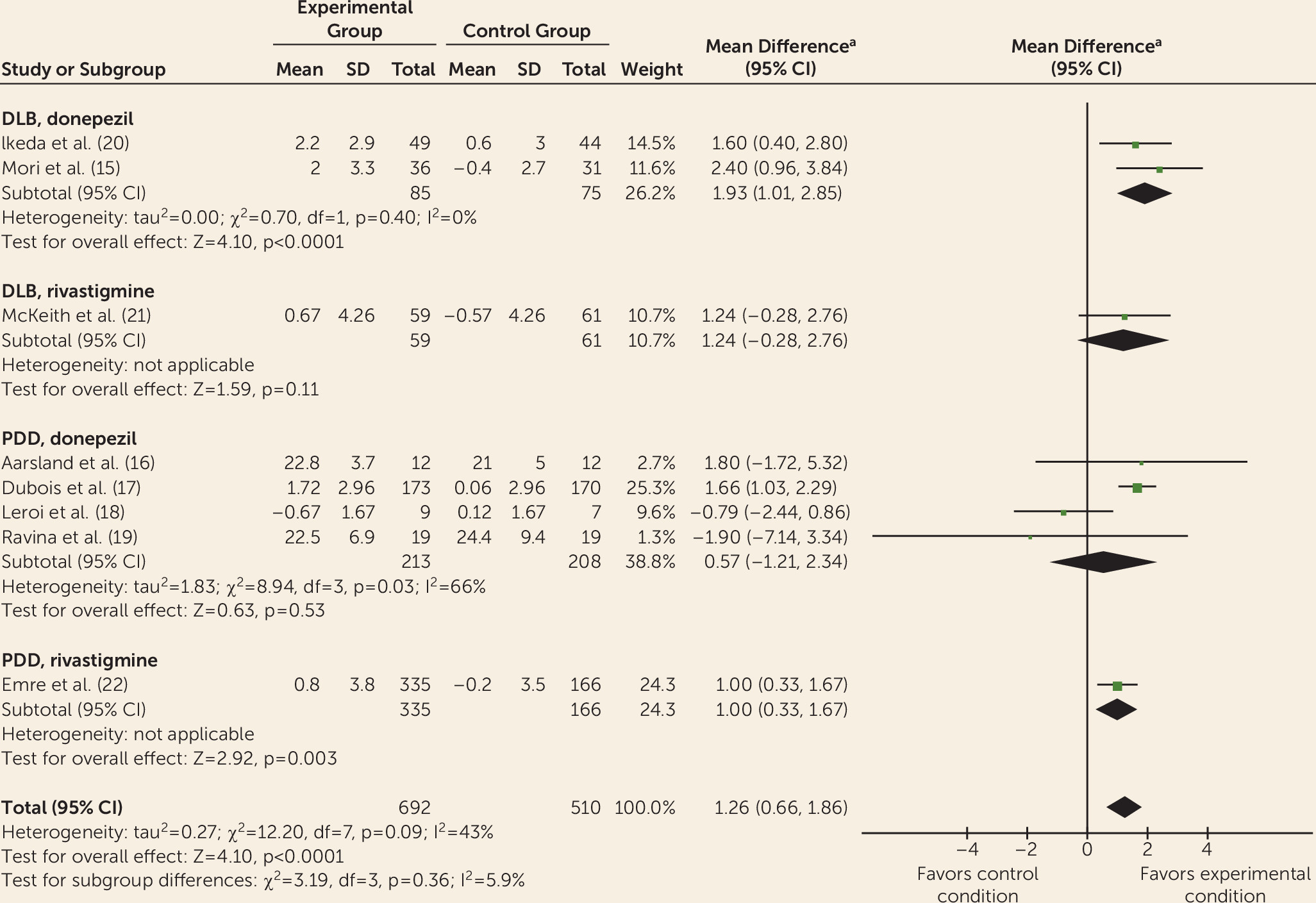

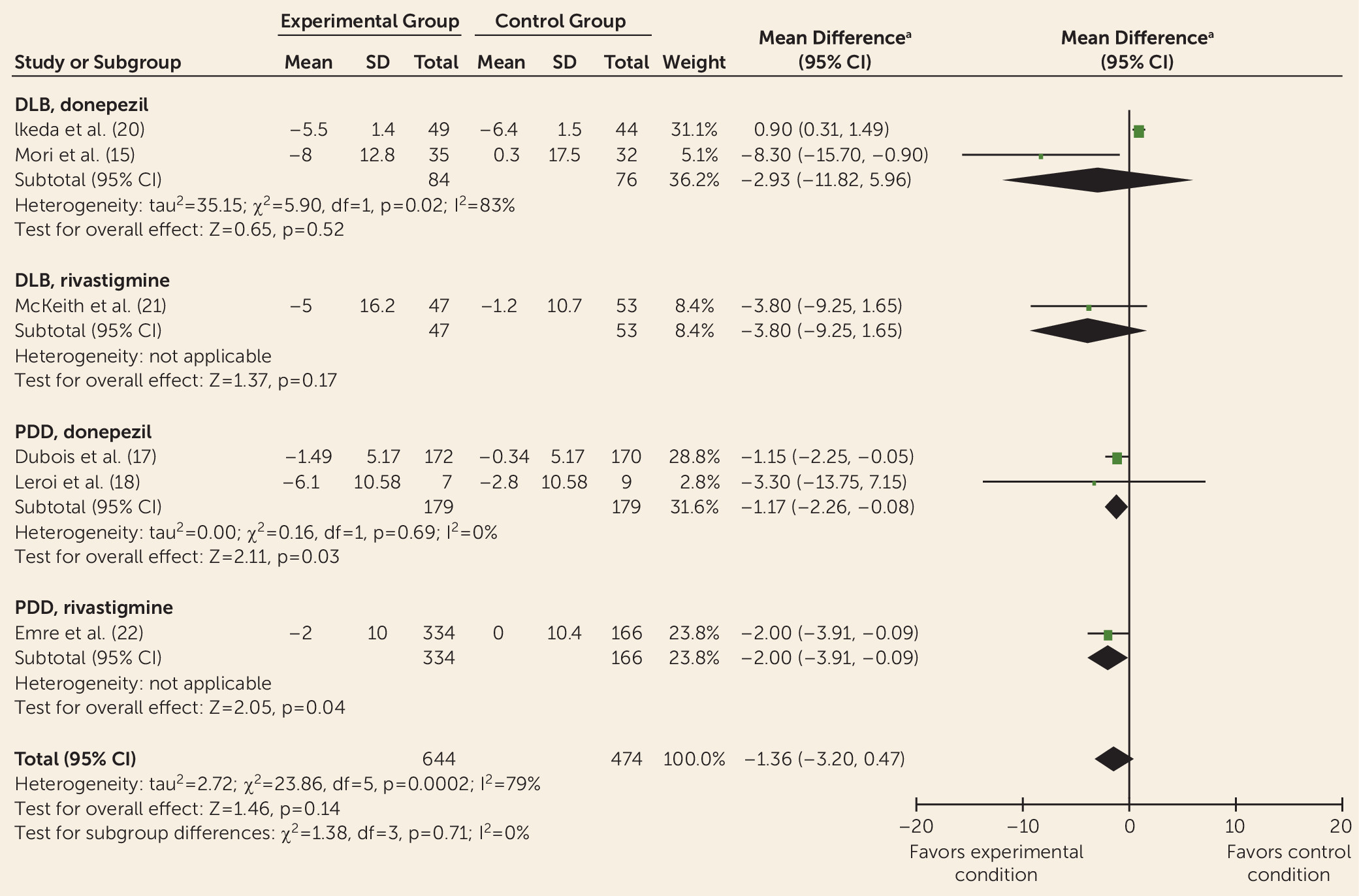

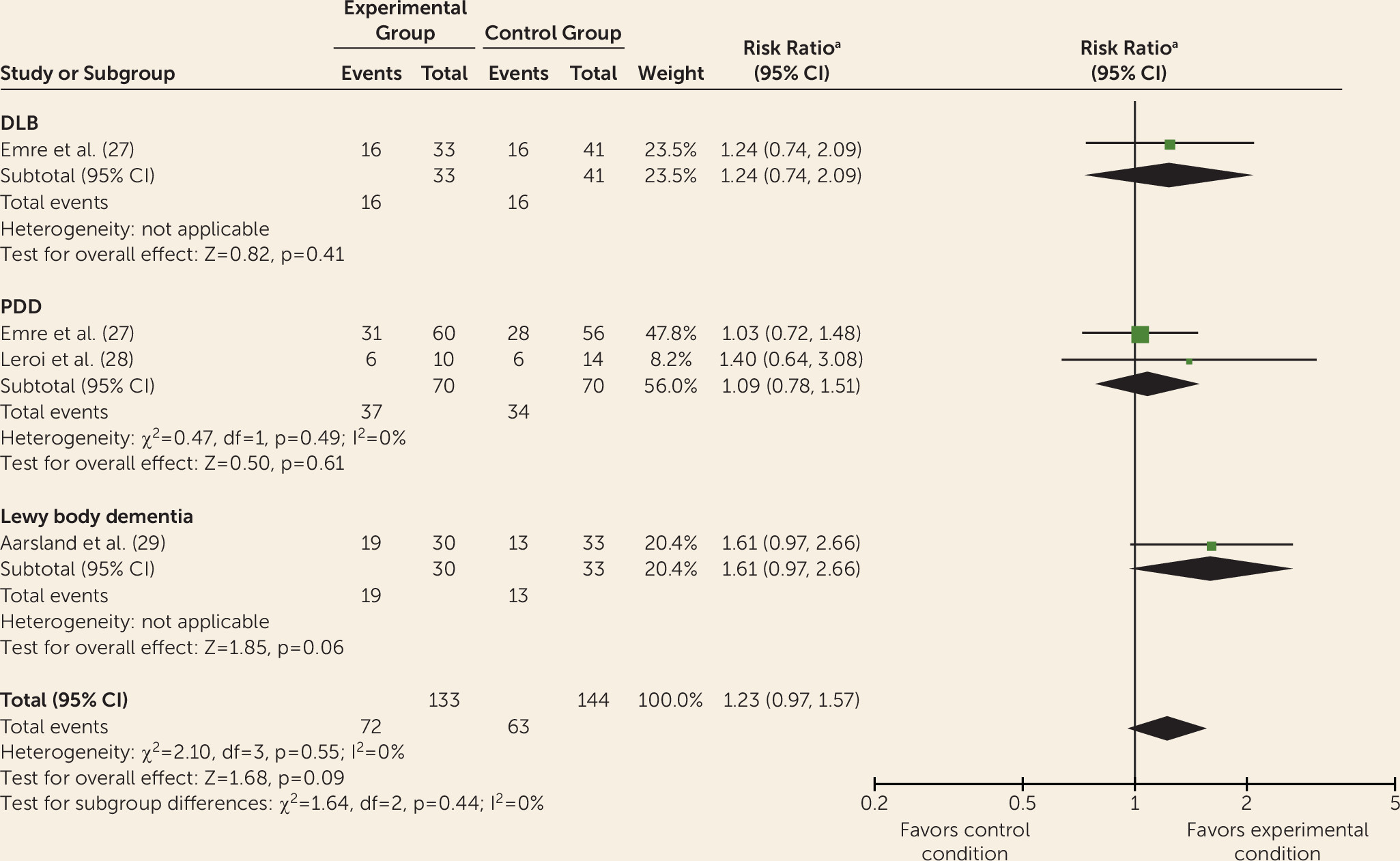

Data from controlled trials were available for donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, memantine, olanzapine, risperidone, piracetam, quetiapine, citalopram, and yokukansan. Meta-analyses indicated improvements with donepezil and rivastigmine for cognition, global psychiatric symptoms (in PDD only), hallucinations, delusions, and activities of daily living (without worsening motor symptoms of parkinsonism) but with adverse events. This is consistent with previous reviews of cholinesterase inhibitors for Lewy body dementia (

7,

9). Evidence for galantamine suggests potential benefits for psychiatric symptoms and possibly for cognition, but the data are limited. Memantine appears to be well tolerated but provides few benefits to patients. Consistent with previous meta-analyses, memantine was superior to placebo only in terms of impression of change when analyzed as a continuous outcome measure; this advantage was not observed when analyzed as categorical data in terms of improvement or absence of deterioration. Recently published secondary analyses of memantine suggest some statistical advantages of memantine over placebo in relation to aspects of attention, sleep, caregiver burden, aspects of quality of life, and goal attainment (

63–

66). For olanzapine and quetiapine, reductions in psychiatric symptoms appear to be limited by high levels of adverse events. Citalopram, piracetam, and risperidone do not appear to be beneficial. Data are mixed on yokukansan for psychiatric symptoms.

There was weak evidence for potential efficacy of armodafinil/modafinil, levodopa, zonisamide, ramelteon, clonazepam, gabapentin, rotigotine, duloxetine, escitalopram, trazodone, and clozapine. These studies did not include controls, so we can conclude only that there could be an association between interventions and benefits to participants. Amantadine and selegiline do not appear to be effective for managing symptoms of Lewy body dementia, but data are available from only single trials or small samples. Overall, we must be cautious not to overstate the apparent effects, or lack of effects, given how few high-level studies are available for each strategy.

Limited data are available on costs of pharmacological strategies. We identified two studies indicating that donepezil and rivastigmine may not be cost-effective, as overall treatment costs were not significantly different compared with placebo groups, and estimates are typically above the threshold of £30,000 per quality-adjusted life-year for treatment, a cutoff often considered cost-effective. However, patents on these drugs have since expired, and cheaper generic versions are now available.

To date, only a small number of studies have investigated associations between treatment efficacy and participant characteristics. The results, which must be treated with caution, suggest a better response to levodopa among younger participants with DLB (

36), a greater benefit from rivastigmine for cognition (global cognition, attention) in patients who have hallucinations (

67,

68), and a greater benefit from rivastigmine for aspects of cognition and global neuropsychiatric symptoms among patients with elevated plasma homocysteine levels (

69). In general, there is insufficient evidence on how, when, and where management strategies should be implemented.

Differing treatment effects between DLB and PDD have received little attention, but some differences are apparent. For example, quetiapine has some benefits for psychiatric symptoms among some patients with DLB but has shown a general lack of efficacy and adverse effects in PDD (

47,

48), and levodopa appears to be more beneficial for PDD than DLB (

36). Our meta-analyses suggest that the effects of donepezil and rivastigmine are comparable for DLB and PDD. Other studies suggest similar effects of donepezil in both groups (

70). Overall, a lack of direct comparison hampers our ability to clarify differences in treatment effects. An additional caveat is the uncertainty about whether DLB and PDD are separate diseases; the 1-year rule for distinguishing the diagnoses is provided only as a guide for clinical practice (

4).

A notable outcome from our review is a potential disconnect between research trials and the reality of clinical practice and the preferences of patients or caregivers. For example, patient-related outcomes and symptom-specific measures were rarely used, and apparent benefits of strategies were typically determined on the basis of statistical rather than clinical significance. Furthermore, no studies were identified on the views that patients with Lewy body dementia or their caregivers have of pharmacological management strategies. Research that focuses on areas of need reported by patients with Lewy body dementia and their families may provide useful information about which strategies to employ.

This review has a number of limitations. First, the evidence base is small. Even for the most well researched management strategies, there were few randomized controlled trials. Second, studies were affected by a variety of issues related to risk of bias and study quality, including open-label study designs, lack of control groups, small samples, and concurrent use of medications that may obscure the effects of study drugs. Furthermore, the accuracy of the diagnostic criteria for DLB and PDD is not clear, with diagnoses in some cases applied retrospectively (

43). Third, research on pharmacological management strategies for Lewy body dementia has usually taken the form of efficacy studies. While these are important in establishing therapeutic effects under highly controlled circumstances, the results are not necessarily generalizable to clinical practice. For example, in research trials, samples are often homogeneous, interventions are standardized without scope for flexibility, concurrent treatments or comorbid conditions are not allowed, and patients with more severe difficulties may be less likely to be recruited or to participate. Effectiveness studies provide a way to address some of these concerns. Fifth, it was necessary to estimate missing information for our meta-analyses, as we were not able to obtain original data from study authors. Sixth, studies of management strategies that are used in clinical practice and have been recommended in expert opinion reviews were not included, because data for groups with DLB or PDD were not available. For example, in Parkinson’s disease, there is evidence from randomized controlled trials that pimavanserin and clozapine may be useful in treating psychotic symptoms in patients with lower cognition (

71).

In summary, in this comprehensive review of pharmacological management strategies for DLB and PDD, we have identified the current best evidence for many key areas of need. There remain substantial gaps in our knowledge of patient and caregiver experiences, of cost-effectiveness, of how, when, and with whom strategies should be implemented, and of how meaningfully the results of studies translate to clinical practice.