People with serious mental disorders die years younger than the general population, with cardiovascular disease as the largest contributor to excess mortality (

1). Compared with the general population, people with serious mental disorders are at risk for poor-quality medical care (

2), and poor-quality care is likely an important determinant of adverse outcomes in this population (

3,

4). These findings have led to a growing call from advocates and providers to improve access to and quality of general medical care for people with serious mental illness. However, only a handful of studies have examined these approaches using rigorous study designs (

5).

One model that has attracted particular interest among providers and policy makers is the behavioral health home, a medical health home based in a community mental health center (

6). Most of these programs are structured as partnerships between community mental health centers and Federally Qualified Health Centers, safety net clinics that receive federal funding to provide primary care services to poor and underserved populations. Since 2009, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's Primary and Behavioral Health Care Integration (PBHCI) program has funded a total of 185 community mental health centers to develop behavioral health homes for their enrollees, with Federally Qualified Health Centers representing approximately two-thirds of primary care partners (

7). Behavioral health homes are being used in a wide range of settings nationwide, including state Medicaid Health Home waiver programs (

8) and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation demonstration projects (

9).

Despite the widespread interest in and use of behavioral health homes, there are few data evaluating their impact on quality or outcomes of care. RAND’s 2013 evaluation of the PBHCI program (

10) compared three grantees to three matched clinic sites from the same states. The study produced mixed results, with improvements in several but not most of the cardiometabolic outcomes and no difference in behavioral health indicators. The report concluded that clinics were able to successfully implement the programs but that there was a need for prospective randomized trials to better assess the impact of these care models on patient outcomes.

To fill these gaps in knowledge, the present study uses a randomized design to rigorously evaluate the impact of a behavioral health home on quality and outcomes of care in a sample of patients with comorbid serious mental illness and cardiometabolic risk factors. The program was implemented in a community setting under real-world conditions, with the intervention delivered by the Federally Qualified Health Center rather than research staff.

Method

The study was a single-blind randomized trial of a behavioral health home compared with usual care for patients at a community mental health center. The intervention lasted 12 months. The study protocol was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board.

Recruitment, Eligibility, and Randomization

Participants were screened and enrolled using a two-stage process. During the first stage, potential subjects were identified from a list of active patients at the community mental health center or referred by mental health providers. Inclusion criteria included presence of a serious mental illness (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder, with or without comorbid substance use), by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (

11), and confirmed via the patient’s community mental health center chart. The exclusion criterion was cognitive impairment, as indicated by a score ≥3 on a 6-item validated screen (

12).

Patients who met preliminary eligibility criteria were invited back to the community mental health center for a fasting screening test for metabolic abnormalities. To be eligible, patients had to have at least one of the following cardiometabolic risk factors: blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg, glucose level ≥100 mg/dL, serum cholesterol level >240 mg/dL, and LDL level >160 mg/dL (

13–

15). Patients who met eligibility criteria and provided informed consent were randomly assigned to either the behavioral health home or usual care.

Intervention Groups

The behavioral health home was established on-site at the community mental health center by the Federally Qualified Health Center. The clinic provided care for participants’ cardiometabolic risk factors and comorbid medical problems. Clinic staff included a part-time nurse practitioner with prescribing authority and a full-time nurse care manager, both supervised by the Federally Qualified Health Center’s medical director. This is the most common staffing pattern used in behavioral health homes (

7). A treat-to-target approach was used for the cardiometabolic risk factors, with weekly supervision meetings focusing on patients whose test results were not within normal range for blood pressure, glucose level, or cholesterol level (

16). The care manager provided health education for lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, diet) and logistical support to ensure that patients were able to attend their medical appointments. Both providers attended weekly rounds at the community mental health center to facilitate integration with the mental health team. After each medical or care management visit, the Federally Qualified Health Center provider entered a note remotely into the center’s chart, with a copy placed into the community mental health center chart. Patients with a usual source of care at baseline who were assigned to the intervention group had the choice of switching providers or receiving care from the behavioral health home as a supplement to their existing treatment.

For the usual care group, patients were provided with a summary of their laboratory tests and encouraged to make an appointment with a community medical provider. They were then given a list of providers near the community mental health center that provided discounted care and/or accepted Medicaid. This reflects typical care provided in the clinic, which provided services consistent with standards of care typically seen in community mental health centers, such as routine blood pressure testing and cardiometabolic laboratory tests for patients taking antipsychotic medications, but did not provide any wellness or primary care services.

Quality and Service Use Measures

The Service Use and Resource Form, a self-report service use instrument was used to identify and request charts from all medical and behavioral health facilities where a subject reported receiving care. Chart reviews were then used to assess health care utilization and quality of care. A full list of the quality and service use measures is provided in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article.

Quality indicators for management of cardiometabolic risk factors were drawn from medical records using indicators from RAND’s Community Quality Index study (

17–

19). These indicators were developed based on literature reviews documenting reliability, construct validity, and linkage with clinical outcomes (i.e., identifiable health benefits to patients who receive guideline-concordant care) (

20).

The study used seven indicators for hyperlipidemia, 13 for hypertension, and 11 for diabetes, each covering domains of screening, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up (

21). A quality score for each condition is generated by dividing all instances in which recommended care is delivered by the number of times a participant is eligible for the indicator. A total quality score across conditions is generated, representing the total number of services for which an individual is eligible that were received by that individual. Quality of preventive medical services and eligible populations were derived from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, with 11 indicators used for the study (

22). All RAND and preventive service quality measures are listed in the

online data supplement.

Participants also completed the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care survey, which assesses the extent to which patients with chronic illness receive care that aligns with the chronic care model. Subscales document the degree to which care is patient-centered, proactive, and planned and the extent to which it includes collaborative goal setting, problem solving, and follow-up support. The instrument has been found to have good test-retest reliability and to be correlated with measures of primary care and patient activation (

23).

Outcome Measures

Fasting blood levels of glucose, fractionated cholesterol, and hemoglobin A

1c (HbA

1c) were collected by the research interviewers every 6 months, using the Cholestech point-of-care fingerstick system, which has been shown to produce values that are comparable to those from gold-standard laboratory tests for cholesterol, glucose, and HbA

1c (

24,

25). Participants were asked to fast for 12 hours before these assessments. The Framingham risk score, an aggregate measure that predicts the 10-year risk of developing incident coronary heart disease (

26), was calculated at baseline and 12-month follow-up using these values in conjunction with information about age, blood pressure, smoking status, and diabetes.

The 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) is a measure of health-related quality of life constructed for use in the Medical Outcomes Study (

27). For the present study, physical and mental component summary scores (

28) were used to provide indicators of health-related quality of life. Patient activation, which reflects an individual’s capacity to manage his or her illness, was assessed using a validated brief version of the Patient Activation Measure (

29,

30).

Data Analysis

Three time points were used for instruments administered during interviews (baseline, 6-month interview, and 12-month interview), and two time points were used for data collected via chart review (baseline, 12-month interview).

All analyses were conducted as intent to treat. First, to assess adequacy of randomization, bivariate analyses were used to examine differences between the intervention and usual care groups. All analyses were generated using SAS/STAT, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). The PROC MIXED procedure was used for continuous variables, incorporating a compound symmetric covariance structure. For each outcome measure, the model assessed the outcome as a function of 1) randomization, 2) time since randomization, and 3) group-by-time interaction. The group-by-time interaction, which reflects the relative difference in change in the parameters over time, was the primary measure of statistical significance.

All hypotheses were two sided and tested at a significance threshold of 0.05. We prespecified a composite primary endpoint (overall quality of cardiometabolic care) to minimize type I error (i.e., false positives) and used a p threshold of 0.05 for secondary outcomes in order to minimize the potential for type II error (i.e., false negatives).

Additionally, mixed models were run separately for cases and controls to determine whether significant changes occurred within each randomized arm. For these models, a significant time effect indicated a change in the modeled outcome.

Results

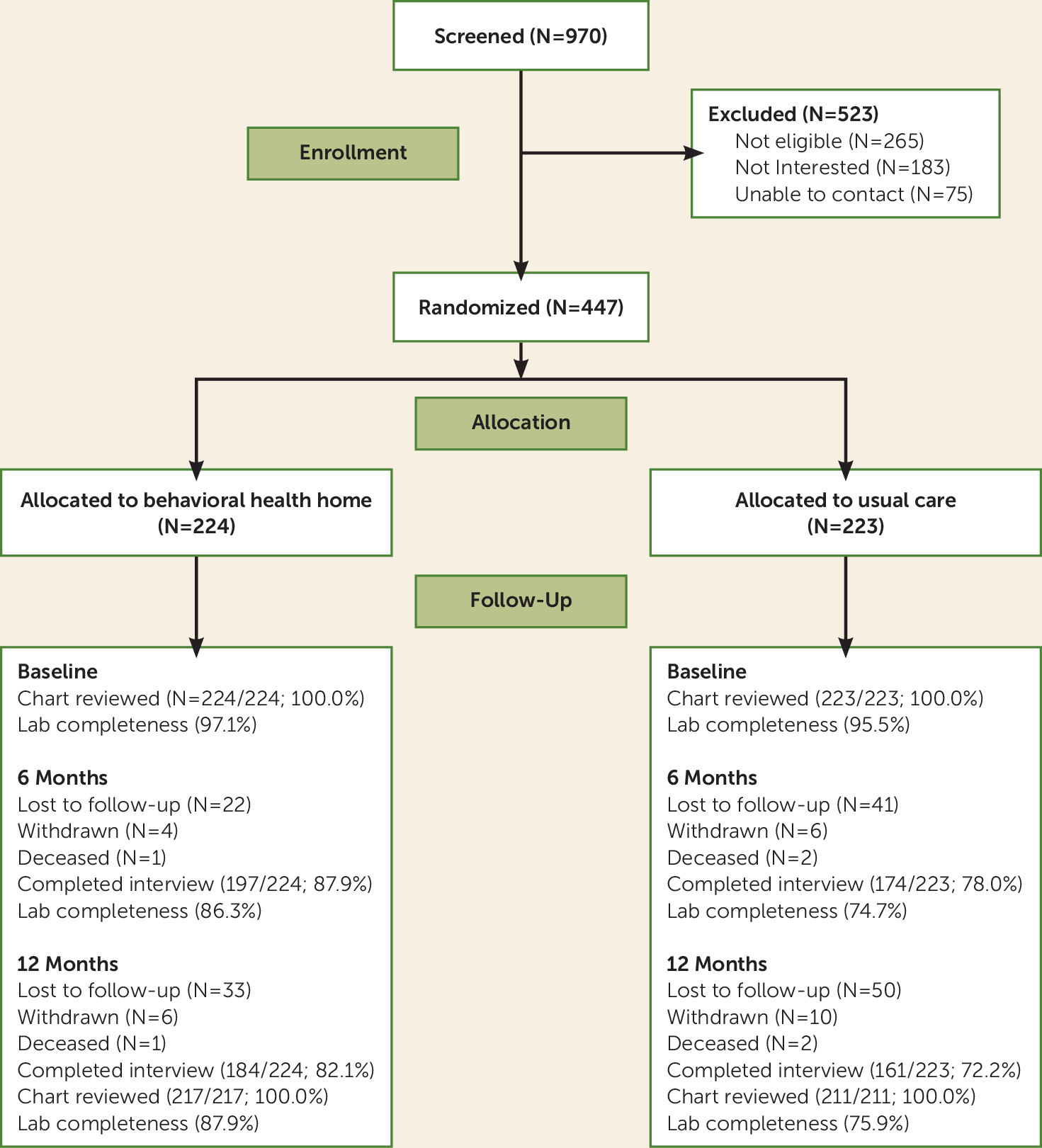

Of approximately 2,000 active patients in the clinic, 970 were screened and 447 were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned to either the behavioral health home or usual care (

Figure 1). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants were similar to those of the overall clinic population.

The two study groups did not differ in any demographic or diagnostic characteristics (

Table 1), which suggests that the randomization was successful. At the 12-month follow-up, a total of 77.2% patients completed interviews (82.1% in the behavioral health home group and 72.2% in the usual care group), 100% in both groups had chart review data, and 81.3% had fasting laboratory data (87.9% in the behavioral health home group and 75.9% in the usual care group).

Quality of Care

The primary study outcome measure was a composite measure of quality of cardiometabolic care, based on RAND quality indicators representing the total number of services for which patients were eligible that they actually received (

Table 2). Patients in the behavioral health home group demonstrated significant improvements in the proportion of indicated services they received (from 67% to 81% in the behavioral health home group and from 65% to 63% in the usual care group; p<0.001). This difference represents a Cohen’s d value of 0.7, a large effect size.

For RAND quality measures for individual conditions, there was a significant difference in improvement for diabetes care (from 38% to 63% in the behavioral health home group and from 41% 44% for the usual care group; p<0.001 for the group-by-time interaction) and hypertension care (from 71% to 84% for behavioral health home group, compared with a drop from 71% to 66% for the usual care group; p<0.001). Care for dyslipidemia improved in both groups but the difference fell short of significance (from 62% to 96% for the behavioral health home group, and 55% to 74% in the usual care group; p=0.06). For the subset of questions specifically focused on quality of medication treatment, patients with diabetes in the intervention group were more likely to receive diabetes medication (81.0% compared with 67%; p=0.04), and those with hypertension were more likely to receive therapy for hypertension (92% compared with 75%; p<0.01).

There was also a significantly greater improvement on prevention services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in the behavioral health home group compared with the usual care group (from 36% to 56% and from 36% to 33%, respectively; p<0.001). The difference between the two groups is a Cohen’s d value of 1.2, a large effect size.

Scores on the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care indicated that care for patients in the behavioral health home was more likely to align with the chronic care model than did care for those assigned to usual care. Out of a possible score of 5, the behavioral health home group improved from 2.2 to 3.6, compared with 2.3 to 2.6 for the usual care group (p<0.001 for the group-by-time interaction).

Service Use

For patients in the behavioral health home group, primary care visits increased from a mean of 0.93 during the 6 months prior to enrollment to a mean of 1.73 in the second 6 months of the program, as compared with an increase from 0.65 to 0.86 in the usual care group. The group-by-time interaction effect was statistically significant (p<0.001). None of the differences across the groups for any other service use measures were statistically significant (

Table 2).

Outcomes of Care

Most clinical outcomes, including diastolic blood pressure, total and LDL cholesterol levels, blood glucose level, HbA

1c level, Framingham risk score, patient activation, and the physical component summary of the SF-36, did not show a differential improvement between the behavioral health home and usual care groups (

Table 3). For all variables except blood glucose level, the behavioral health home group showed a significant improvement between baseline and 12-month follow-up. However, the usual care group also showed improvements in all outcomes except blood pressure, blood glucose level, and HbA

1c level, with the result that there was not a significant difference between groups in change in these outcomes over time. There were modest statistically significant differential improvements between the groups in the mental component summary (an improvement of 8.1 points in the behavioral health home group, compared with 7 points in the usual care group; p=0.03) and in systolic blood pressure (improvements of 4.9 points and 3.1 points, respectively; p=0.04) (

Table 4).

To better understand whether differential loss to follow-up could have affected the study findings, we compared the baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of participants with follow-up data to those who dropped out of the study. Participants who dropped out were significantly younger on average than those who completed 12 months of follow-up (mean age, 44.8 years compared with 47.7 years; p=0.01) and were less likely to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia (11% compared with 22%). There were no other significant differences in any demographic or baseline cardiometabolic parameters between the two groups. (See Table S2 in the online data supplement for full results.)

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized study of a behavioral health home, and it is one of only a handful of randomized trials examining medical homes that have been conducted to date (

31). For patients with serious mental illness and cardiovascular risk factors, the behavioral health home was associated with significant benefits with regard to quality of general medical care, cardiometabolic care, and concordance with the chronic care model. However, there was not a significant effect on most clinical outcomes, including cardiometabolic parameters.

Across a range of indicators, participants with serious mental illness and cardiovascular risk factors who were enrolled in the behavioral health home received care of a significantly higher quality compared with those assigned to usual care. It is notable that the findings were stronger and more consistent than the effect of medical homes in the general medical sector (

31,

32), which have found a more limited impact of medical homes on quality of medical care. This positive impact on quality of care is notable given the fact that the behavioral health home delivered care under real-world conditions, with broad inclusion criteria and use of Federally Qualified Health Center staff rather than research staff to deliver the intervention. It demonstrates that it is possible to deliver high-quality care even under the challenging circumstances seen in community mental health centers, with high levels of comorbidity, functional disability, and social disadvantage.

However, the behavioral health home did not have an impact on the majority of cardiometabolic and medical outcomes. Both study groups demonstrated significant improvements in cardiometabolic outcomes between baseline and 12-month follow-up, and it is possible that screening and community referral were enough to partially improve outcomes in the usual care group. For patients who were unaware of their conditions or were not motivated to seek care, a recommendation to seek care from a community provider might help engage patients and motivate their mental health providers to refer them to treatment. However, caution should be used in interpreting within-group improvements, as they are based on observational data and may reflect factors unrelated to the study.

Poor quality of care is only one factor underlying adverse medical outcomes in patients with serious mental illness and cardiometabolic risk (

33). Behavioral factors such as poor diet, smoking, and lack of physical activity also raise cardiovascular risk and early mortality in this group (

34,

35). Several recent studies have demonstrated that it is possible to improve diet (

36,

37), physical activity (

38,

39), weight (

36,

37,

39), and smoking (

40) in patients with serious mental illness. However, there is more limited evidence that lifestyle programs improve cardiometabolic outcomes or overall cardiovascular risk in populations with serious mental illness (

41,

42). In general medical populations with coronary heart disease, intensive multifactor risk models that combine medication with lifestyle change have demonstrated promise in improving aggregate outcomes, including risk of fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events (

43). Future research should examine the potential benefits of programs combining medical care and lifestyle factors, tailored to the clinical needs and socioeconomic challenges faced by patients with serious mental illness (

44).

There are several limitations that should be considered in interpreting the study findings. First, there were more dropouts from the usual care group than the behavioral health home group. While we did not find any significant between-group differences in baseline clinical or demographic characteristics among study dropouts, we cannot rule out the possibility that this group improved more or less than those who remained in the study. Second, it is possible that larger improvements in quality of care or a longer intervention duration would have resulted in better clinical outcomes. Further research should be conducted to assess how best to optimize medical quality under real-world conditions in behavioral health homes. Third, the Framingham risk score is not an optimal outcome measure, since it includes factors such as age that are not sensitive to change, and it does not factor in characteristics that are unique to patients with serious mental illness. There is a need to develop high-quality aggregate outcome measures that can meaningfully capture the full range of modifiable risk factors that contribute to early mortality in patients with serious mental illness (

45). Finally, the study was conducted in a single behavioral health home. It is possible that other clinics might have better or worse outcomes based on differences in patient factors (e.g., differing diagnostic case mix), organizational factors (e.g., Federally Qualified Health Center versus other primary care partners), or community resources (e.g., nearby specialty medical clinic options for referral).

The results suggest that it is possible, even under challenging, real-world conditions, to improve the quality of medical care for patients with serious mental illness and cardiovascular risk factors treated in community mental health settings. However, better quality alone may be insufficient to improve more distal medical outcomes. Addressing the poor clinical health and early mortality in this population will require multimodal strategies addressing the full range of risk factors that underlie these problems.