T

o the E

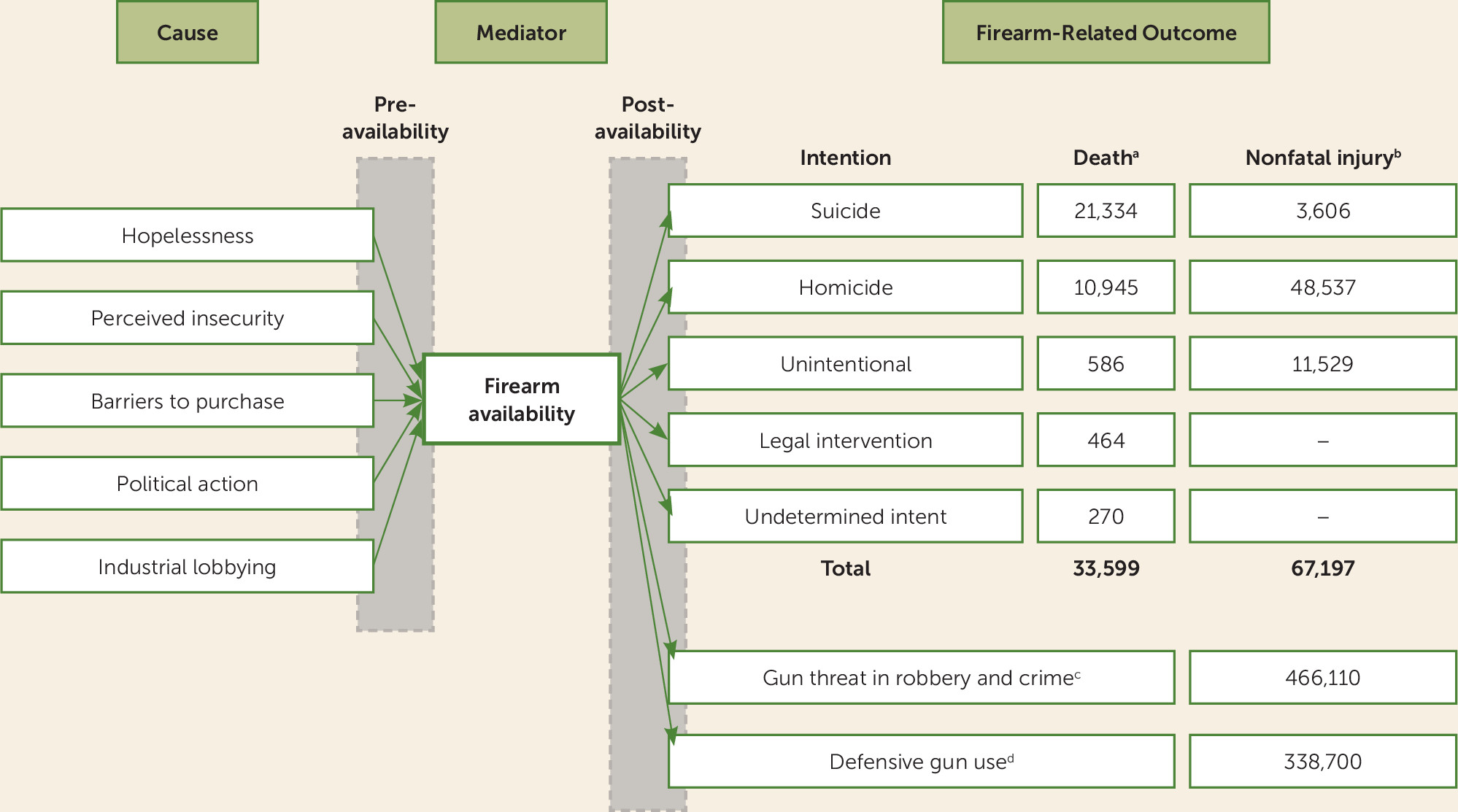

ditor: An often-cited purpose of firearms in the United States beyond sports and hunting is to defend oneself against criminal acts. Indeed, firearms are designed to threaten, injure, or kill. The dilemma is that firearm misuse for other purposes is frequent (

Figure 1). As reviewed by Mann and Michel (

1) in the October 2016 issue of the

Journal, there is considerable evidence for the effectiveness of interventions, such as restrictive laws, to prevent firearm suicide. However, the authors offer a rather pessimistic view concerning the possibility to translate these results into practice, based on two arguments.

First, suicides are often committed using firearms that are purchased long before suicidal acts, and recent data show that firearms are available in 43% of U.S. households (

2), ready for use and misuse. Such ubiquity of firearms suggests an inevitable situation, which seems to be propelled by the second argument: the Second Amendment protecting the right of citizens to keep and bear arms. This argument is underpinned by the Supreme Court’s decision upholding this right of each individual. According to Mann and Michel (

1), these facts undermine universal prevention efforts and force prevention programming toward targeted restrictions in high-risk populations, such as suicidal or aggressive individuals exposed to firearms.

Withdrawing from universal prevention in favor of high-risk approaches has some considerable limitations. When exposure to a pathogenic agent (firearm availability within the U.S. population) is rather homogeneously distributed and common, the largest number of cases (firearm misuse) happen not in those at high risk but in those with low levels of risk (

3). This goes hand in hand with the problem to appropriately predict high-risk persons in the general population. Even though some recent advances have been made in predicting suicide (

4), this progress comes only in severely mentally ill populations under clinical observation. Indeed, emphasis on high-risk approaches derives from a clinical view, but it is necessary to keep in mind that population-based prevention efforts have some advantages, such as a larger preventive potential because of control of causes in the whole population. We suggest that prevention of firearm suicide and violence needs to target all aspects along the causal chain of firearm misuse, its societal causes, and individual-level circumstances. An integrated, multilevel approach should therefore address preavailability factors (universal prevention) and postavailability misuse (individual high-risk approach). As long as postavailability strategies such as gun violence restraining orders or enhanced psychological evaluation of high-risk persons (

5) are not effective, the universal strategy to reduce firearm availability by law cannot be omitted.

Finally, firearm suicides inherently contain a hypnotic ambiguity because both the intention of suicide and the intention of firearms seem to coalesce into a permissive attitude toward risk behavior. The right to bear arms is a socially constructed pathogenic agent that generates tremendous costs for postavailability preventive programs. Restriction would radically cut all associated costs and be effective.