Comprehensive specialty care treatment for early psychosis has been strongly advocated (e.g.,

1), and several randomized comparisons have been conducted (

2–

8). Given the critical role of medication treatment, it is notable that comprehensive specialty care interventions have varied widely in how much medication treatment was specified and that such limited information has been provided on treatment goals and guidelines, prescriber training, and treatment delivery. In published articles, medication prescription was not mentioned for the GET UP PIANO TRIAL intervention (

7); the Specialized Treatment Early in Psychosis (STEP) intervention (

8) included “psychotropic prescription”; Grawe et al. (

3) used antipsychotics “at the lowest effective dose”; the Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) study (

2) intervention employed “low-dose atypical antipsychotic regimens”; the Croydon Outreach and Assertive Support Team (COAST) (

6) used “optimum atypical medication”; and the OPUS early detection and community treatment study (

4) used medication treatment “designed individually according to national guidelines.” In contrast, medication prescription in the NAVIGATE intervention of the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode–Early Treatment Program (RAISE-ETP) included the unique elements of 1) program-developed first-episode medication guidelines, 2) a computerized decision support system to support shared decision making regarding prescriptions, and 3) training and ongoing support for prescribers throughout the study.

We examined NAVIGATE’s effects on prescription practices and measures of general side effects, vital signs, and cardiometabolic outcomes using data from the RAISE-ETP study (

5,

9) comparing NAVIGATE treatment with clinician-choice community care. These analyses complement findings (

5) of better symptom outcomes on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (

10) and the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (

11) with NAVIGATE compared with community care.

Method

NAVIGATE treatment (

12) included coordinated medication management, psychoeducation, resilience-focused individual therapy, and supported employment and education. NAVIGATE team members supported one another’s efforts, including adherence to NAVIGATE medication guidelines. Individual resilience-focused therapy included modules on medications and health-promoting behaviors.

Medication Procedures

Research data and treatment guidelines (

13–

17) support distinctive medication strategies for first-episode and multiepisode patients. Our approach to assisting busy clinicians at our nonacademic “real-world” sites to incorporate specialized first-episode treatment strategies into their work started by developing first-episode medication guidelines based on review of the treatment literature. Medication recommendations were limited to marketed agents, given the community facilities setting. NAVIGATE treatment used a shared decision making model (

18). For medication selection, patients and prescribers chose from among medications with equivalent evidence based on patient factors and preferences. The shared decision making framework plus the failure of any antipsychotic to demonstrate superior efficacy for initial treatment of psychosis led to the decision to group recommended medications into treatment stages instead of a single medication algorithm. In selecting antipsychotic medications for the treatment stage groups, preference was given to medications with data from studies with first-episode or adolescent patients with psychotic disorders. Side effect and treatment efficacy data from these studies were the primary considerations for assigning medications into initial or subsequent treatment groups. Symptom remission rather than symptom improvement was the treatment goal. If a satisfactory initial response was not obtained with an initial stage medication, medications were chosen from subsequent stage groups. The antipsychotics that were available in the United States during guideline development and for which data were available from contemporary studies with first-episode or adolescent populations were aripiprazole, chlorpromazine, clozapine, haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. Because of concerns about side effects with chlorpromazine, clozapine, haloperidol, and olanzapine and concerns about lower efficacy for maintenance treatment with haloperidol (

19,

20), these medications were excluded from the stage 1 group, which thus consisted of the remaining studied agents: aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. Stage 2 agents were the stage 1 agents plus chlorpromazine, haloperidol, and olanzapine. Clozapine was a stage 3 agent. For each medication, first-episode dosing guidelines were developed (e.g., for risperidone, a starting dosage of 1–2 mg/day, a target dosage of 3–4 mg/day, and a maximum dosage of 8 mg/day). Over the 2-year RAISE-ETP treatment duration, continuous antipsychotic treatment was recommended. Patients and prescribers evaluated the potential benefits and disadvantages of switching antipsychotics for participants who entered RAISE-ETP with prescriptions that did not conform to NAVIGATE stage 1 principles. Participants who agreed to take antipsychotic medication but not a NAVIGATE-preferred medication were treated with their preferred agent. Participants who declined to take any antipsychotic had ongoing prescriber monitoring visits. Strategies were also provided for managing side effects (dosage reduction being the usual initial step) and for monitoring and treatment of cardiometabolic abnormalities. Since depressive symptoms in first-episode patients often remit with antipsychotic treatment alone (

21), prescription of adjunctive antidepressants for all first-episode patients with depressive symptoms was not advised. Instead, consideration of the persistence and severity of depression was suggested when making decisions about adjunctive antidepressants. The detailed NAVIGATE medication manual is available online (

22).

Participants and prescribers used COMPASS, a NAVIGATE-developed computerized clinical decision making tool accessed via a secure web-based platform. COMPASS was designed to facilitate patient-prescriber communication. Participants entered information about symptoms, side effects, treatment preferences, medication adherence and attitudes, and substance use into COMPASS before meeting with their prescribing clinicians. Vital signs data and laboratory test results were also entered. These data were summarized by the COMPASS program for review by the prescriber at the beginning of each medication visit. NAVIGATE medication treatment used a measurement-based approach to guide treatment decisions. The standardized assessments done by the prescriber at each visit were informed by the previously entered participant data (e.g., the COMPASS-suggested probe questions for prescribers were modified at each visit based on the responses on the participant questionnaire, and the prescriber assessment screens displayed the participant’s responses to the corresponding item on the participant self-report screens). Integrating participant treatment priorities and the prescriber’s assessments, COMPASS provided suggested guideline treatments. Prescribers and participants then made medication decisions informed by these recommendations. NAVIGATE guidelines recommended a prescriber visit at least monthly for the first 2 years of treatment.

NAVIGATE prescriber training included a 2-day group session on NAVIGATE principles, followed by individual training via teleconferencing on technical aspects of COMPASS. Monthly group prescriber teleconferences with the NAVIGATE central team included group feedback about challenging clinical cases and NAVIGATE treatment options for them, along with review of relevant psychosis literature.

The RAISE-ETP Study

This report focuses on the first 2 years of patient participation, the minimum by design for all participants. Patients 15–40 years of age receiving treatment for a first episode of psychosis due to schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified and who had taken antipsychotics for ≤6 months during their lifetime were recruited from 34 community mental health treatment facilities nationwide that did not have preexisting first-episode specialty care programs. Written informed consent was obtained from adult participants; for participants under 18, written consent was obtained from parents or guardians and written assent from participants. RAISE-ETP was conducted under the guidance of the institutional review boards at the coordinating center and the various sites, as well as the National Institute of Mental Health’s Data and Safety Monitoring Board.

RAISE-ETP employed cluster randomization. The 17 randomly assigned NAVIGATE sites recruited 223 participants, and the 17 community care sites recruited 181 participants. Community care clinicians were trained on recruitment, informed consent, and study assessment procedures but received no guidance on treatment approaches. The study design and assessments have been described previously (

9). Monthly patient self-report data on prescriptions (medications and dosages) and on number of medication management visits were obtained with the Service Use and Resource Form (

23). At baseline and at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months, participants reported in a yes/no format whether they had experienced, during the past 30 days, any of 21 common side effects of antipsychotic medications (dizziness, blurred vision, dry mouth, excess saliva, nausea, constipation, increased appetite, weight gain, weight loss, restlessness, shaking, rigidity, fatigue, drowsiness, excess sleep, insomnia, decreased libido, other sexual problems, breast swelling or discharge, impaired sexual performance, and amenorrhea). Concurrently, vital signs were obtained and fasting blood samples were collected. Participants taking medications also completed the Adherence Estimator, a self-report scale (

24) measuring beliefs related to intentional nonadherence that has been validated against pharmacy claims (

25).

Statistical Analysis

As RAISE-ETP participants had psychotic disorders, our paramount medication question was whether NAVIGATE, compared with community care treatment, was associated with a greater likelihood of antipsychotic prescription. We also compared the likelihood of participants receiving a prescription that conformed to NAVIGATE stage 1 (“first-line”). We determined, by study month, whether participants received prescriptions for antipsychotic monotherapy with a NAVIGATE stage 1 antipsychotic. We allowed a broad range of antipsychotic dosages (instead of our targeted dosage ranges) to qualify as first-line to allow for low dosages for antipsychotic initiation and higher dosages for management of treatment resistance (for example, the qualifying dosage range for risperidone was 1–8 mg/day, based on 1 mg/day being the NAVIGATE recommended lowest starting dosage and 8 mg/day the highest dosage). Participants receiving concurrent stimulants were classified as not receiving prescriptions for first-line medications; participants receiving antipsychotic monotherapy with paliperidone at approved dosages were classified as receiving a first-line medication prescription (NAVIGATE training included review of the administration advantages of paliperidone palmitate over risperidone microspheres). Given that depression outcomes were better with NAVIGATE than with community care, we also compared the likelihood of receiving an antidepressant prescription in the two conditions. In addition to these explorations of medication groups, we wished to characterize choice of specific antipsychotic agents and dosages prescribed. For this, we examined the likelihood of the most commonly used agents being prescribed (irrespective of dosage or other medications prescribed) and the mean modal dosage for the oral formulations of each agent.

The primary measure for general side effects was the total number of side effects (excluding amenorrhea, as it is not applicable to male participants). Secondary measures were amenorrhea and a priori side effect groupings (sedation, extrapyramidal symptoms, anticholinergic side effects, increased appetite or weight gain, and sexual problems). A side effect group was considered present if any side effect within that group was present.

Longitudinal analyses of the any-antipsychotic-use (yes/no) outcome and other binary outcomes were performed using a generalized linear mixed-models analysis with a logit link. PROC GLIMMIX in SAS, version 9.4, was used. Each subject’s modal dosage was calculated, and the mean modal dosage was compared between conditions using a mixed-models analysis with a random intercept for site. Longitudinal analysis of the cardiometabolic outcomes and total number of side effects was performed with mixed models using the PROC MIXED procedure in SAS. The mixed-models approach takes into account the within-subject correlation of the repeated measurements. The difference in the trajectories between the two treatment groups was assessed by including a time-by-treatment interaction term in the mixed models. Least square means, which estimate the population marginal means for a balanced design, were computed. In all longitudinal analyses, cluster correlation within site was addressed by including a random intercept for subjects nested within sites. The limited number of clusters in clustered randomized trials can cause an imbalance between treatment groups on baseline measures, potentially confounding the relationship between treatments and outcomes. In accordance with the overall RAISE-ETP statistical analysis plan (

5,

26), variables with significant baseline group imbalance were included as covariates in our analyses if they were correlated with the outcome of interest at a level ≥0.30.

Adjustment for multiple comparisons was done by controlling the false discovery rate using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (

27,

28). The R multtest package was used. False discovery rate correction was applied to groups of analyses that addressed the same clinical question. The blocks were medication classes prescribed, specific agents, daily dose, vital signs, laboratory findings, number of side effects, and specific side effects. Significance was declared for analyses with false discovery rate–corrected p values <0.05.

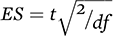

Odds ratios from the analyses of medication classes and specific agents were converted to Cohen’s d using the formula

. Elsewhere, effect sizes of the difference between least square means were calculated using the formula

, where

t is t-value and

df is degrees of freedom.

Results

Participants

The participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table S1 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article. Overall, 73% were men, and the mean age was 23 years. The most frequent racial categories were Caucasian (54%) and African American (38%), and the most frequent diagnoses were schizophrenia (53%) and schizophreniform disorder (17%).

COMPASS Implementation

Of the 223 NAVIGATE participants, 211 (94.6%) completed one or more COMPASS visits. During their first 2 years of study participation, NAVIGATE participants collectively completed 3,004 COMPASS assessments.

Number of Medication Visits

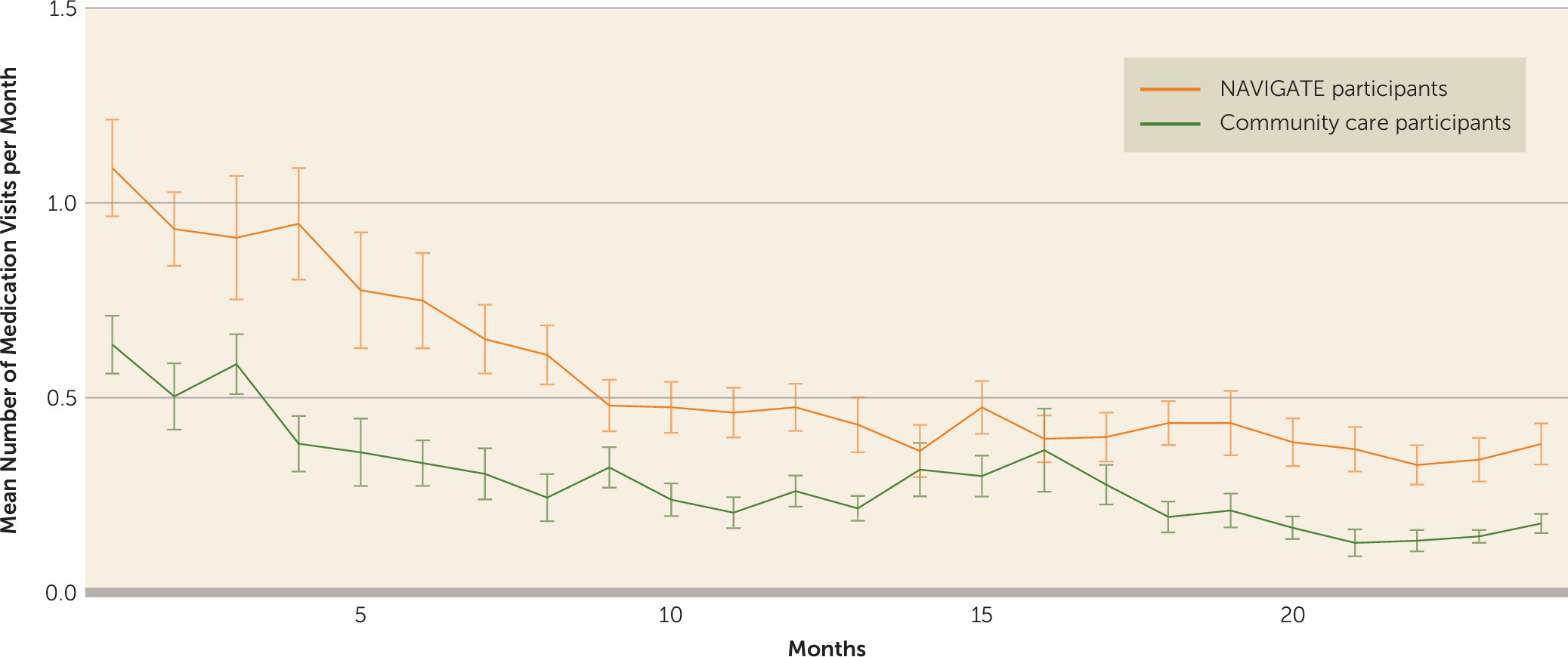

As illustrated in

Figure 1, NAVIGATE participants had significantly more medication visits compared with community care participants (treatment-by-time interaction, F=3.78, df=23, 9246, p<0.001; effect of treatment, F=12.80, df=1, 9246, p<0.001). Over the 2 years, the least squares mean estimate of the number of medication visits per month was 0.29 (95% CI=0.23, 0.36) for the community care group and 0.55 (95% CI=0.42, 0.69) for the NAVIGATE group.

Medication Prescription

As shown in

Table 1, NAVIGATE participants were significantly more likely compared with community care participants to receive an antipsychotic prescription (odds ratio=3.73, 95% CI=1.71, 8.16) and less likely to receive an antidepressant prescription (odds ratio=0.39, 95% CI=0.16, 0.94).

Over the trial, NAVIGATE participants were more likely to receive prescriptions conforming to NAVIGATE first-line principles (odds ratio=2.19, 95% CI=1.08, 4.42). Prescriptions at study entry for NAVIGATE and community care participants were equally likely not to conform with NAVIGATE first-line principles (t=−0.49, df=744, p=0.63). In post hoc analyses of participants who were not receiving a NAVIGATE first-line prescription at baseline, 62.7% of the 110 NAVIGATE participants later received a NAVIGATE first-line prescription, compared with 44.4% of the 90 community care participants (odds ratio=2.07, 95% CI=1.02, 4.16; t=2.11, df=31, p=0.043).

As shown in

Tables 1 and

2, the specific antipsychotics prescribed and the mean modal daily dose did not significantly differ between conditions for any of the major antipsychotics. NAVIGATE participants were more likely than community care participants to receive prescriptions for aripiprazole and less likely to receive prescriptions for haloperidol, although these differences fell short of statistical significance.

Vital Signs and Cardiometabolic Measures

As presented in

Table 3, both weight and body mass index (BMI) analyses revealed significant treatment-by-time interactions. The estimated mean increase in BMI from baseline to month 24 was 2.10 (95% CI=1.32, 2.89) for the NAVIGATE group and 2.45 (95% CI=1.90, 2.99) for the community care group; the corresponding estimated weight gain was 6.51 kg (95% CI=4.61, 8.41) kg for the NAVIGATE group and 7.31 kg (95% CI=5.62, 9.00) for the community care group. No significant treatment-by-time interactions or treatment effects were detected in analyses of other vital signs data or of lipid or carbohydrate metabolism measures.

General Side Effects

Analysis of the number of medication side effects revealed a significant treatment-by-time interaction. As shown in

Table 4, NAVIGATE and community care participants reported equal numbers of side effects at baseline, but NAVIGATE participants reported fewer side effects at subsequent visits (the difference was significant at months 6 and 12 and fell short of significance at months 3, 18, and 24). A secondary analysis controlling for antipsychotic prescription similarly revealed an advantage for NAVIGATE treatment (treatment-by-time interaction, F=2.88, df=5, 1087, p=0.004). Table S2 in the

online data supplement presents the analyses of side effect groups. NAVIGATE participants were significantly less likely to have sedation or anticholinergic side effects; they were also less likely to have extrapyramidal symptoms, appetite increase, and sexual dysfunction, although these differences fell short of significance.

Adherence Estimator Scale

Scores on the Adherence Estimator scale did not differ between groups at baseline, and they decreased (indicating fewer beliefs associated with nonadherence) significantly among NAVIGATE but not community care participants (treatment-by-time interaction, F=2.46, df=5, 940, p=0.032). Least squares mean estimates of baseline and 24-month scores were 8.33 (SE=0.86) and 6.087 (SE=0.69) with NAVIGATE (change decrease of 2.24 [SE=1.06]) and 7.12 (SE=0.80) and 7.90 (SE=0.81) with community care (change increase of 0.78 [SE=0.93]).

Discussion

The NAVIGATE model was developed to treat a specialized population, patients with first-episode schizophrenia and related disorders, in nonacademic “real-world” settings. An initial question was whether the COMPASS decision support system could be implemented and used in community settings. The 3,004 completed COMPASS visits provide an affirmative response to this question. Furthermore, NAVIGATE participants had on average nearly twice as many monthly medication management visits (0.55 compared with 0.29) as community care participants, and the pattern of more NAVIGATE medication visits was present across all trial phases. These findings support the sustained feasibility and acceptability of the NAVIGATE treatment model in comparison with usual care. NAVIGATE prescribers had the support of a manual, training by the central team in treatment principles and COMPASS use, the guidance that was built into the COMPASS visits, and access to monthly teleconferences.

The next key question was whether NAVIGATE recommendations and the COMPASS system influenced prescriptions. Prescriptions for any antipsychotic as well as prescriptions conforming to NAVIGATE first-line antipsychotic principles were significantly more likely with NAVIGATE compared with community care. Prescriptions for specific antipsychotics did not differ significantly. Although the difference fell short of statistical significance, aripiprazole prescriptions were more likely and haloperidol prescriptions less likely for NAVIGATE participants, consistent with NAVIGATE-preferred medication stages. Clozapine was required only infrequently with our first-episode population. Rates of clozapine prescription were greater with NAVIGATE than with community care (4.7% compared with 1.8% of months with prescription data), but the difference was not significant. Given the NAVIGATE emphasis on low-dose strategies, we anticipated that NAVIGATE prescriptions would be for lower dosages. Instead we found no differences, probably resulting from the finding that the mean modal dosages for community care antipsychotic prescriptions overall were within recommended first-episode treatment ranges.

In a previous analysis of medication prescription at RAISE-ETP entry (

29), 39.2% of participants were found to be receiving problematic prescriptions. An important question is whether rates of problematic medication prescriptions change during extended treatment. Differences in data sources available at baseline and longitudinally precluded applying the previous baseline criteria to the present longitudinal analyses. Prescriptions that do not conform with NAVIGATE first-line principles may be clinically appropriate (e.g., for symptoms that do not improve with a first-line medication). Nevertheless, the extent to which patients with baseline prescriptions that do not conform to NAVIGATE first-line principles later receive a first-line prescription does provide one metric to evaluate whether prescription patterns improve over time. It is encouraging that substantial numbers of community care participants initially receiving prescriptions that did not conform with NAVIGATE first-line principles eventually received a NAVIGATE first-line prescription and that NAVIGATE significantly increased the likelihood of this change compared with community care treatment.

We reported previously (

5) that NAVIGATE participants had lower levels of depressive symptoms. The present analysis shows that this was achieved with significantly less likelihood of antidepressant prescription. This may reflect the finding that the depressive symptoms of patients with first-episode psychosis often remit with antipsychotic treatment alone (

21), and this information was included in NAVIGATE training. Furthermore, the NAVIGATE psychosocial interventions (

12) may have contributed to better outcomes for depressive symptoms. A recent meta-analysis (

30) found small beneficial effects for adjunctive antidepressants for depression and negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. First-episode subgroup analyses did not detect effects, but the number of first-episode studies included was small. Outcomes for negative symptoms in RAISE-ETP did not differ between conditions despite less antidepressant use with NAVIGATE. Further research is needed to determine 1) whether first-episode psychosis specialty care treatment consistently produces better depression outcomes with less antidepressant prescription and 2) what effects (if any) antidepressant treatment has on negative symptoms among first-episode patients.

The lower number of side effects among NAVIGATE participants is notable given that NAVIGATE participants were more likely to receive antipsychotic prescriptions and that the side effects assessed were ones specifically associated with antipsychotic treatment. NAVIGATE training emphasized prevention and minimization of side effects, and the COMPASS system included structured side effect assessments at each visit and decision support for side effect management. These may have contributed to lower side effect burdens from prevention efforts and better detection and treatment of antipsychotic-induced side effects when they occurred. The less frequent use of antidepressants at NAVIGATE sites may also have contributed to the lower number of side effects.

Although outcomes for weight gain and BMI were significantly different between the NAVIGATE and community care groups, the differences were small in magnitude. Nevertheless, given the likely future duration of antipsychotic exposure, such differences are potentially important. Given the potential adverse effects of antipsychotics on lipid and glucose metabolism, it is reassuring that NAVIGATE treatment enhanced antipsychotic prescription compared with community care while producing similar laboratory outcomes. Nevertheless, the mean weight gain of 6.5 kg among NAVIGATE participants shows that additional tools for preventing adverse metabolic outcomes are needed.

Medication data from other comparisons of comprehensive first-episode specialty care with usual care are limited. Broadly, data from our trial and others (

31,

32) and from demonstration projects (

33) suggest that comprehensive care treatment may be associated with better medication treatment. Intervention compared with control condition participants in the LEO trial were significantly less likely to stop prescribed medication (

31), and in the OPUS trial, more likely (although short of statistical significance) to be taking an antipsychotic at 1 year but not at 2 years (

32).

A limitation of RAISE-ETP medication data is the reliance on patient self-report. Self-report was necessary as a source instead of clinic or pharmacy records to permit medication tracking for participants who discontinued treatment at their RAISE-ETP site. Patient self-report may have introduced inaccuracies in the overall data, but it should have had a limited impact on comparisons of NAVIGATE and community care, as participants in both conditions should have had equivalent ability to report on their prescribed treatments. It should be noted that our data are for medications prescribed rather than medications taken. The Adherence Estimator scale data documented an advantage with NAVIGATE but not community care treatment for medication beliefs related to adherence. An important future research question is whether these belief changes translate into improved adherence.

In summary, we previously reported differential improvement with the comprehensive NAVIGATE treatment model compared with community care in quality of life and clinical psychopathology outcomes (

5). We now add findings of greater frequency of antipsychotic prescription, reduced side effect burden, reduced antidepressant prescription, and some reduction of the consequences of antipsychotics on physical health. The NAVIGATE model of measurement-based care in the context of shared decision making provides a framework for incorporating future advances. As knowledge of first-episode medication treatment advances, future medication guideline improvements may produce even better outcomes than our current efforts.