Cigarette use among U.S. adolescents has declined markedly (

1), reflecting successful policy changes and health initiatives. Nevertheless, it remains a persistent problem, with 38% of 12th graders having smoked tobacco cigarettes (

2) and the rising popularity of e-cigarettes prompting a new warning from the Surgeon General (

3). Because nicotine is the substance most consistently linked to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (

4), clarifying precisely how ADHD contributes to smoking is imperative. Toward this objective, prospective clinical samples have established that adolescents with ADHD are more likely to initiate smoking early (

5) and escalate to daily smoking (

6). Prevention of these earlier stages of smoking, which mediate associations between genetic risk and nicotine dependence (

7), is essential.

Yet evidence for whether female adolescents with ADHD are at heightened risk for substance problems, as males are, relative to adolescents without ADHD, has been inconsistent (

8–

10). With these few exceptions, most prospective clinical samples of children with ADHD in studies that include substance use outcomes are largely or exclusively male (

11). ADHD was long considered to occur much more frequently in males than in females, and males were more likely to be referred by teachers for treatment (

12). Inclusion of a predominantly inattentive subtype in DSM-IV identified more females, however, and DSM-5 reports an approximate 2:1 male-to-female ratio for ADHD in the general population. Accordingly, population-based samples are well suited for studying both genders. However, they often struggle to recruit enough females with clinically significant ADHD, leaving unresolved the question of whether male and female adolescents bear similar risk.

Moreover, although childhood ADHD typically begins prior to smoking initiation, we cannot assume that it has a causal link to smoking. The association may result instead from overlapping risk factors that increase the likelihood of both ADHD and smoking. For example, some prospective research casts doubt on whether ADHD confers a specific risk apart from co-occurring conduct and oppositional defiant disorders, or suggests that its contribution may be limited to a specific symptom subtype (

13). Other prospective research has found that although conduct disorder reduced its effects, hyperactivity-impulsivity was still associated with an increased likelihood of initiating smoking and developing dependence (

14), although this independent association may be stronger for females (

15). There is also evidence that inattention and nicotine dependence may be particularly related (

14,

16).

While a study of cousins, full siblings, and half siblings discordant for ADHD suggested that ADHD–drug disorder associations appeared to be due partially to causal influence (

17), monozygotic twin pairs who differ in ADHD might provide more definitive evidence of causality. Because monozygotic twins reared together share essentially the same genetic sequence and rearing environment, differences within monozygotic pairs can only be due to unique, nongenetic influences (

18). If differences within dizygotic but not monozygotic pairs are found, this would suggest that genetic factors influence both ADHD and smoking, as dizygotic pairs share only 50% of their segregating genetic material. Familial environment is an important confounder if within-pair differences are absent, since both twin types share factors in the rearing environment, including socioeconomic status and prenatal nicotine exposure.

In the present study, prospective and twin difference designs were combined to explore the etiology of adolescent smoking in twins discordant for ADHD. We examined whether differences within pairs in number and type of ADHD symptoms might lead to differences in smoking, along with gender moderation of effects. This quasi-experimental, causally informative design integrates genetic and social science perspectives and provides critical information for public health initiatives (

19). Because the sensitivity of the twin difference design decreases when twin correlations on the putative causal factor are high (

20), combining multiple data sets helps ensure adequate statistical power for detecting significant within-pair differences in monozygotic pairs, particularly when testing whether effects are moderated by gender.

We hypothesized two mechanisms through which ADHD might accelerate nicotine involvement: 1) a shared externalizing propensity, represented primarily by hyperactivity-impulsivity, increases the likelihood of both ADHD and smoking; and 2) a nonshared, specific influence of inattention increases smoking. We hypothesized that this specific influence may be more salient for female adolescents. Because females typically have more inattentive than hyperactive-impulsive symptoms and experience greater impairment from inattention in academics and peer relationships during childhood (

21), we examined whether risks from inattention extended to adolescent smoking. We also determined whether effects persisted after taking into account nonshared exposures that predate ADHD (e.g., birth weight), co-occurring externalizing disorders (i.e., conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder), and stimulant medication use. By combining data sets, including a cohort that oversampled affected females, and using dimensional measures and multiple informants, we enhanced the statistical power to identify within-pair differences and gender moderation.

Method

Participants

A total of 3,762 individuals (52% of them female) visited with parents at baseline. The sample comprised 1,881 like-sex twin pairs (64% of them monozygotic) from three community-ascertained cohorts in the Minnesota Twin Family Study, a longitudinal investigation of the development of substance abuse. Twin pairs born in Minnesota identified from birth records were eligible if they lived within a day’s drive of the University of Minnesota and had no physical or psychological disability that would preclude completing the assessment.

One cohort was assessed at age 17; two were assessed at age 11 and followed to age 17. In one 11-year-old cohort, pairs were randomly allocated to screened and nonscreened samples. The nonscreened sample was recruited using the criteria listed above. In the screened cohort, the parent was interviewed to enrich the sample with twins who showed academic disengagement and externalizing disorder symptoms. The family was recruited if at least one twin exceeded an empirically validated threshold that maximized sensitivity and specificity for identifying cases of externalizing disorders (

22). A higher allocation of females to the screened sample ensured participation of more affected females. After a complete description of the study was given, written informed consent was obtained from the parents and written assent from the twins. Based on information obtained prior to recruitment, there were no significant differences between participating and nonparticipating families on parent-reported mental health or socioeconomic status. Thus, the combined sample was representative of the Minnesota population for the target birth years (e.g., 91%−98% were white; for further detail, see references

22,

23).

Assessments for all cohorts overlapped at age 17, and age 17 data were available for 92.5% of the combined sample. Retention in the two prospectively followed cohorts was excellent, with no selective loss of those with more ADHD symptoms at baseline. Assessment of the cohort assessed only at age 17 was cross-sectional. A description of the sample and the data utilized at each wave is provided in Figure S1 in the data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article.

Measures and Procedures

Nonshared exposures were indexed by birth weight from birth certificates, and neurological injuries from parental report. A composite measure of socioeconomic status represented the mean of four standardized scores: highest parental occupation status, mother’s and father’s highest degree, and household income.

Each parent and child was interviewed by a different interviewer, each of whom had a degree in psychology (or a related field) and extensive training. Primary caregiver reports on twins, including lifetime ADHD before age 12 (consistent with DSM-5 onset) and DSM-IV nicotine dependence by age 17, were obtained with the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents–Revised (DICA-R) (

24), modified to include DSM-IV criteria. Twin reports of ADHD before age 12 (e.g., asking “When you were younger…”) were obtained with a parallel version of the DICA-R. Lifetime conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder were also assessed at baseline with the DICA-R. Self-reported nicotine dependence was assessed in twins at age 17 via a modified, expanded substance abuse module from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (

25).

Symptoms were assigned by consensus of two individuals with advanced clinical training (supervised by a Ph.D.-level clinical psychologist). A symptom was considered present if it was reported by parent or child and if its frequency and severity met pre-established guidelines. Combining informants is recommended for etiological investigations involving ADHD, and inclusion of twin self-ratings is essential for detecting differences within pairs (

26). Because different diagnostic systems were in place when each cohort was assessed, symptom counts were harmonized with DSM-IV (e.g., the inattentive count was pro-rated by multiplying by 1.5 for earlier cohorts assessed on only six of nine DSM-IV inattentive symptoms). Although analyses were based on symptom counts rather than diagnoses, many adolescents had clinically relevant ADHD: 337 males and 201 females had five or more symptoms of either the predominantly inattentive or the hyperactive-impulsive subtype or both (combined), including impairment.

Three composites reflecting highest level of smoking by age 17 were derived from items added to the substance abuse module of the CIDI and a self-administered computerized measure: earliest initiation age reported across assessments; progression to daily smoking (0=none; 1=initiated, never daily; 2=daily smoker since age 16 only; 3=daily smoker before age 16); and cigarettes per day during heaviest use, adjusted for nondaily use (0=none; 1=1–2 cigarettes; 2=3–9 cigarettes; 3=half a pack [equivalent to 10 cigarettes]; 4=one pack or more [equivalent to ≥20 cigarettes]). When applicable, equivalent use of chewing tobacco was incorporated.

Statistical Analyses

Because none of the correlations between birth weight or neurological problems and either inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms in monozygotic or dizygotic pairs differed significantly from zero, these were not considered further. Choice of regression models was based on each outcome’s distribution. Age at initiation was explored via survival models implemented in the COXPH package in the R statistical program. Data were censored for those whose initiation status was still unknown by age 17. We used a gamma between-within model recommended for co-twin survival analysis (

27), which uses a Wald test of β=0, distributed as χ

2 with one degree of freedom. For progression to daily smoking, ordinal regression with proportional odds models was implemented in the MIXOR package in R. For cigarettes per day and nicotine dependence, linear mixed models with maximum likelihood estimation were implemented in SAS PROC MIXED; nicotine symptoms were log-transformed prior to analysis.

Individual-level models were fitted using either the inattentive or the hyperactivity-impulsivity symptom count as the predictor of each of the four smoking outcomes. Individual-level models treated twins as individuals, yet accounted for correlations within pairs and generated appropriate standard errors (

28) through random intercepts at the cluster (pair) level or shared frailty terms (for survival models [

27]). Next, twin difference models divided significant individual-level effects of inattention or hyperactivity-impulsivity into those shared by twins in a pair (twin-pair average) and nonshared (within-pair difference). The within-pair effect thereby represents the unique effect of ADHD after controlling for all shared confounders, measured or unmeasured. Models were conducted separately by gender if gender moderation was significant at the individual level. If the within-pair effect was significant, whether this differed for monozygotic and dizygotic pairs was assessed. Models were repeated with monozygotic and dizygotic pairs only to obtain separate estimates for each. Power was estimated at 80% for detecting monozygotic-within-pair effects accounting for 0.7% of the variance in smoking outcomes and for detecting differences between male and female monozygotic-within-pair estimates accounting for 1.2% of the variance (see the

online data supplement).

Results

Descriptive data regarding highest levels of smoking in the combined sample were consistent with aggregated trends for U.S. adolescents from 1990 to the present (

1), including significantly greater smoking among male than female adolescents (

Table 1). Consequently, ADHD effects on smoking were adjusted to remove confounding from specific demographic covariates, including gender, cohort, socioeconomic status, and age at assessment. Although adjusting overall (i.e., individual-level) effects of ADHD for shared covariates reduced their size, all were highly significant (p<0.0001).

In

Table 2, adjusted effects are listed for inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity. Estimates are provided separately by gender when gender moderation was significant. Effects on initiation are reported as hazard ratios, reflecting an increased likelihood of initiating smoking during any specific year; effects on progression to daily smoking are reported as odds ratios. Both reflect increases associated with a one-symptom increase in inattention or hyperactivity-impulsivity. For the cigarettes per day and dependence analyses, ADHD symptoms, cigarettes per day, and nicotine symptoms were converted to standardized scores (mean=0, SD=1) based on the entire sample. Regression estimates for these models reflect the smoking increase associated with a one standard deviation increase in inattention or hyperactivity-impulsivity.

Adolescents with more inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were more likely to initiate smoking (and to do so earlier), without significant gender moderation. Hazard ratios associated with individual-level effects on initiation were 1.16 and 1.24, indicating that the rate of initiation increased 16% for each inattentive and 24% for each hyperactivity-impulsivity symptom. However, for female relative to male adolescents, ADHD was associated with faster progression to daily smoking (i.e., inattention by gender: z=2.01, p<0.05; hyperactivity-impulsivity by gender: z=3.19, p<0.002), more cigarettes per day (inattention by gender: F=12.09, df=1, 1689, p<0.001; hyperactivity-impulsivity by gender: F=11.00, p<0.001), and more nicotine dependence symptoms (inattention by gender: F=7.04, df=1, 1704, p<0.02; hyperactivity-impulsivity by gender: F=5.78; p<0.02). For instance, a 27% increase in the odds of progressing one level toward daily smoking was observed for each inattentive symptom in female adolescents (19% for males) or 45% for each hyperactive-impulsive symptom (24% for males).

Twin difference effects are presented separately within dizygotic and monozygotic pairs in

Table 2 to identify the source of observed differences, as their combined estimates were always significant for female adolescents (see Table S1 in the

data supplement). For both genders, monozygotic and dizygotic within-pair differences in inattention were significantly associated with initiation, consistent with partial causal influence. Rate of initiation increased 8% with each additional inattentive symptom a monozygotic twin had compared with his or her co-twin. However, all monozygotic- and dizygotic-within-pair estimates for inattention were significantly associated with daily smoking, cigarettes per day, and nicotine dependence for female pairs only (except one for female dizygotic pairs, at p=0.06), with no significant within-pair estimates for males, consistent with causal influence for female adolescents and full confounding by indirect genetic and environmental influences for males. By contrast, for hyperactivity-impulsivity, no monozygotic-within-pair estimates were significant (except for cigarettes per day in females), whereas all were significant for dizygotic pairs (for initiation) or female dizygotic pairs (for other outcomes). The fact that the female dizygotic-within-pair estimate associated with hyperactivity-impulsivity was significantly greater than the monozygotic for nicotine dependence (dizygotic > monozygotic, p<0.05; see

Table 2) implies that genetic differences primarily accounted for female adolescents’ increased smoking risk from hyperactivity-impulsivity.

Because potentially causal effects of inattention may be mediated by conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, or treatment with stimulant medications, individual-level analyses of inattention predicting all four smoking outcomes were repeated, adding either log-transformed conduct/oppositional defiant disorder symptoms at baseline, or ever used prescription stimulants (yes/no), as a covariate. Although conduct/oppositional defiant disorder effects on smoking partially overlapped with those of inattention, they did not affect significant gender moderation effects, nor did stimulants. Whether the possible causal effect of attentional differences on smoking in females was due instead to a greater likelihood of conduct/oppositional defiant disorder (or stimulants) in the more inattentive twin was also evaluated (see the online data supplement). All significant monozygotic-within-pair effects remained, however, except for progression to daily smoking (e.g., the odds ratio declined from 1.19 to 1.17 [p=0.08], when conduct and oppositional defiant disorders were added).

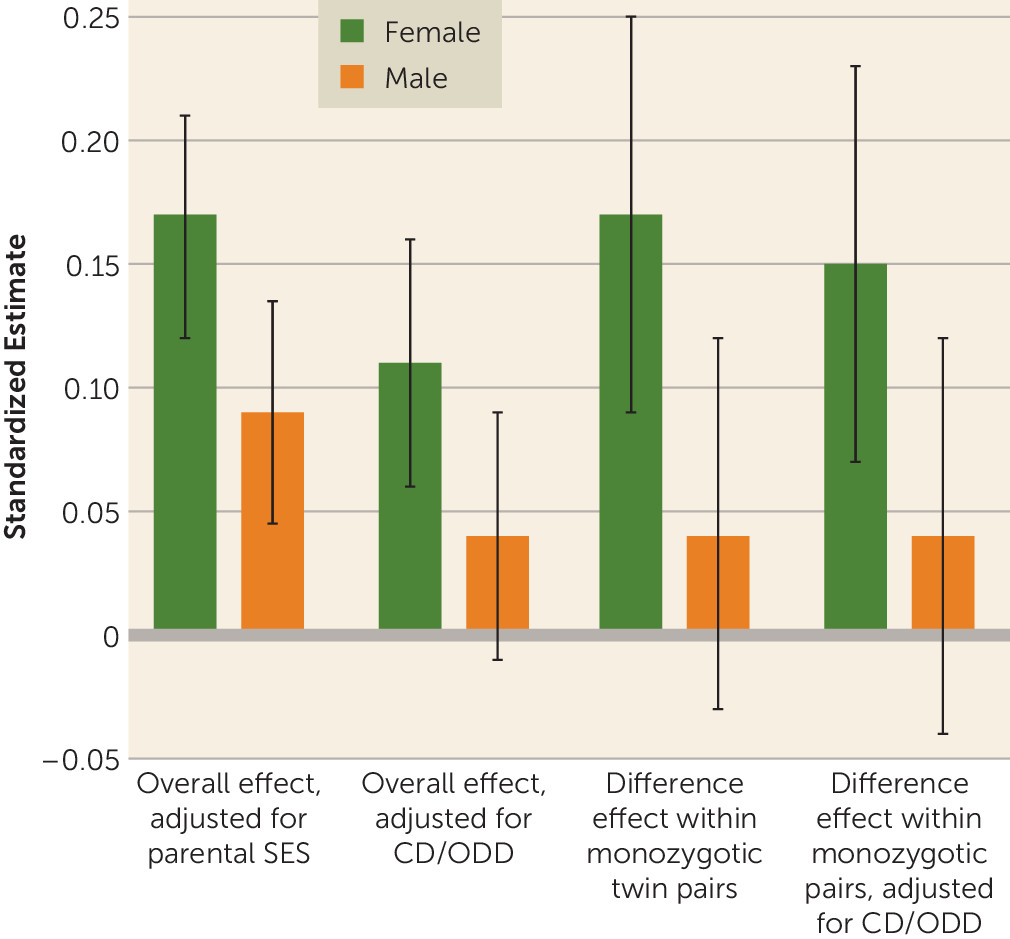

Figure 1 illustrates an example of this consistent pattern for inattention, with nicotine dependence as the outcome. Adjusting for conduct and oppositional defiant disorders lowered the magnitude of the overall individual-level effect attributable to inattention, so it remained significant for female adolescents only; significant female monozygotic-within-pair differences in inattention were minimally affected.

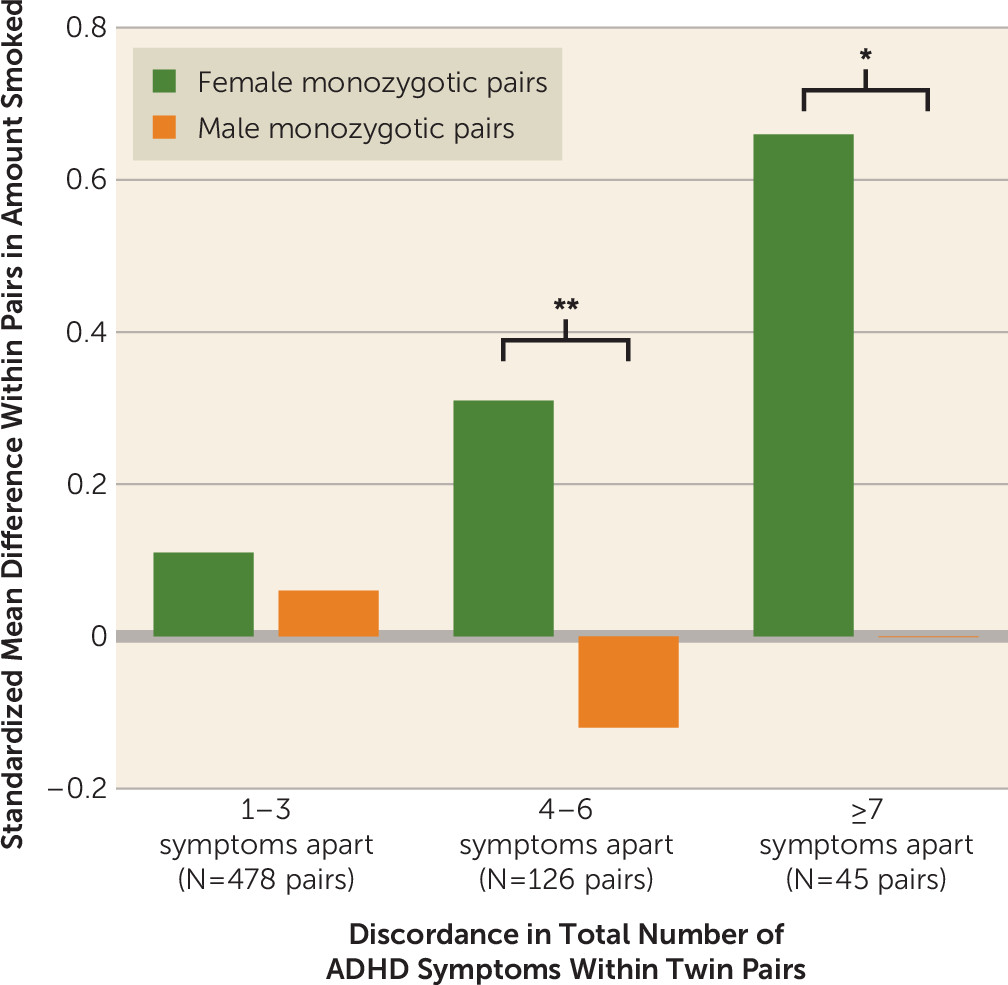

Figure 2 demonstrates the practical significance of twin discordance in ADHD for maximum amount smoked (cigarettes per day), the only outcome with significant female monozygotic-within-pair differences for both symptom subtypes. With shared genes and environment completely controlled, a potentially causal influence of moderate to large effect was evident for female pairs only.

Discussion

In a combined analysis of three population-based cohorts with a significant number of females affected by ADHD, we used a twin difference design to evaluate whether the association of childhood ADHD with smoking is consistent with a possible causal influence. To our knowledge, this is the first twin difference study to address effects of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity on progression of smoking during adolescence. Consistent with previous research (

5,

6), we found that adolescents with more ADHD symptoms were more prone to initiating smoking early and to progressing to heavier, frequent smoking and nicotine dependence by age 17. However, ADHD was reliably associated with a higher level of these smoking risks for female adolescents than it was for male adolescents.

Our findings were also consistent with a causal influence of inattention on smoking initiation in both genders, or on increased smoking involvement in female adolescents only. Attentional differences within monozygotic female pairs were significantly related to differential progression to daily smoking, cigarettes per day, and nicotine dependence. While effect sizes corresponding to each symptom were modest, these effects became consequential for smoking among more discordant pairs (

Figure 2; see Figure S2 on the

data supplement for another example) and were unaffected by co-occurring externalizing disorders (

Figure 1) or stimulant medication. Conversely, for male adolescents, within-pair differences were absent, suggesting that familial factors (e.g., lower socioeconomic status or parental smoking) play a greater role than inattention specifically. Hyperactivity-impulsivity effects in both genders were almost fully confounded by influences common to hyperactivity-impulsivity and smoking, with the exception of cigarettes per day. Thus, consistent with our hypotheses, both causal and noncausal mechanisms may be important in explaining the increased vulnerability of female adolescents with ADHD to smoking.

Mechanisms of Gender Moderation

Support for causality bolsters the plausibility of the premise that nicotine may be used to self-medicate inattention (

13), consistent with findings of a placebo-controlled study that smokers with ADHD experience nicotine-related reductions in symptoms (

29). Furthermore, while nicotine withdrawal is generally associated with negative affect, smokers with ADHD report more severe withdrawal (

30) and concentration difficulties (

6) than those without ADHD. Although prescription stimulants for ADHD have been associated with reduced smoking (

31), in the present study they were associated with neither increased nor decreased smoking or nicotine dependence (similar to findings in reference

32), and they did not ameliorate attentional effects on smoking for females.

Even if inattention is causal, there are likely to be mediators of its effects on smoking in female adolescents. The increased vulnerability of females to peer and academic consequences of inattention (

21) may contribute to greater depression and anxiety among inattentive females relative to inattentive males (

33), increasing their receptivity to nicotine’s effects on attention and mood. Gender differences due to the interaction of ovarian hormones with nicotine and dopaminergic reward-processing systems (

34) may further increase the susceptibility of female adolescents to self-medication.

Shared propensities primarily explain the relationship of hyperactivity-impulsivity to smoking for both genders. Even when familial resemblance is genetic, adverse environments among those with ADHD may be increased through gene-environment interplay (

35). For example, adolescents with externalizing propensities are prone to deviant peer affiliation, and increased exposure to such peers is associated withsubsequent nicotine dependence (

36). That the hyperactivity/impulsivity-smoking relationship might be stronger for female than male adolescents was unexpected, yet it is consistent with evidence that greater risk accumulation may be required for females to develop ADHD (

37).

Could Smoking Cause Inattention Instead?

Apparently causal effects in a twin difference design are sometimes due to “reverse causation” (

18). Thus, smoking might also cause inattention. In the Netherlands Twin Registry (

38), monozygotic twins who smoked showed a larger subsequent increase in attention problems from adolescence to adulthood compared with nonsmoking co-twins. We examined whether reverse causation represents a plausible alternative interpretation of our results by rerunning inattention models using only data from the two prospectively assessed cohorts with ADHD measured at age 11. Although the monozygotic-within-pair effect became marginally significant for initiation (p=0.05), attentional differences within monozygotic pairs were still significantly related to cigarettes per day, daily smoking, and dependence for females by age 17, suggesting that reverse causation does not account for our results. Discrepancies between our findings and those from adults in the Netherlands Twin Registry may be due to etiological differences between childhood and adult ADHD. Childhood inattention may contribute to increased smoking; however, considering the deleterious cognitive effects of adolescent nicotine exposure (

3), nicotine may contribute to increased attention problems later on.

Strengths, Limitations, and Implications

Childhood ADHD appears relatively early in development, and nonshared experiences predating it appeared to be unlikely alternatives to a causal role of inattention for smoking. However, because observational data were used, causality cannot be conclusively proven, and it is possible that an unmeasured, nonshared experience leading to attentional differences in females might partially account for this association (

18) (e.g., early maltreatment of one twin). Conversely, because monozygotic-within-pair estimates are disproportionately reduced by compounding of measurement error, the monozygotic-within-pair association of hyperactivity-impulsivity with amount smoked (cigarettes per day) suggests that there may be partially causal effects of hyperactivity-impulsivity for female adolescents that our study did not have the power to detect. Additionally, although e-cigarettes were not in common use when these data were collected, e-cigarette users are more likely to initiate smoking of conventional cigarettes (

3), and both are nicotine-based. Finally, while our sample was representative of Minnesota, replication among a more diverse sample is needed. The study has many strengths as well. The cohort sequential design ensures that results are not specific to adolescents from one era, and assessment of multiple smoking outcomes with structured interviews and computerized measures increases reliability and provides internal replication.

This study confirms that specific relationships between inattention and smoking observed in previous research may arise partially from causal effects, which has implications for intervention (

16). Diminishing inattention should reduce initiation and progression to heavy smoking, particularly for females. Preventing nicotine exposure among females with ADHD is critical, as adolescent females may be more susceptible to nicotine’s neurotoxic effects (

39). Focusing on coping with inattention and its associated impairments is consistent with evidence that psychosocial therapies may produce greater reductions in ADHD-related impairment than medication alone (

40).