Few neuropsychiatric disorders demonstrate the relationship between neurology and psychiatry as dramatically as frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Although FTD is a common cause of early-onset dementia, it is not common for clinicians other than behavioral and cognitive neurologists to be familiar with its phenomenology, diagnosis, and treatment. But they should be, for the symptoms of FTDs are fascinating, and patients with FTD may initially present to psychiatrists and primary care physicians. Therefore, it is necessary to be acquainted with diagnosis and management, especially as FTD symptoms can be confused with or comorbid with psychiatric symptoms. A patient’s apathy, for instance, may be mistaken for depression, or his delusions for schizophrenia, resulting in erroneous diagnoses and inappropriate treatment.

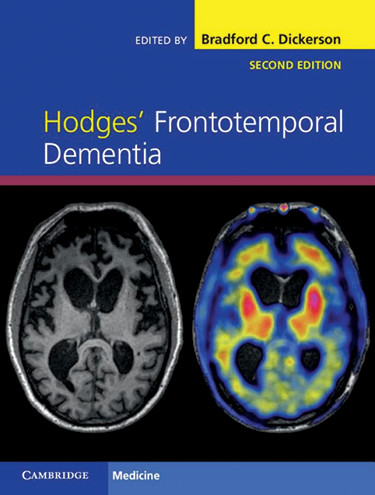

Bradford Dickerson has edited the second edition of John Hodges’ 2007 FTD textbook, and the result is clear and concise, yet comprehensive. The current volume consists of 19 chapters divided into five sections focused on introductory material, clinical phenotypes, diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment of FTD, and most chapters are authored by renowned experts. The level of writing is appropriate for both trainees and clinicians, and there are ample tables and illustrations to clarify the relationships being discussed. Several black-and-white illustrations from various chapters are reproduced in color in a section in the center of the book to allow the reader to see these images in their original form.

John Hodges’ historical introduction opens the book. He traces the evolution of the diagnosis of FTD from Arnold Pick’s original description from 1892 of a patient with progressive aphasia, mental deterioration, and left temporal lobe atrophy to the more recent concepts of the behavioral variant, progressive aphasia, and semantic dementia subtypes, along with genetic and pathophysiological classifications, including their inconsistencies. This section concludes with an overview of the clinical presentations of FTD with a focus on their differential diagnoses and relationships to other neurodegenerative diseases.

The second section consists of five chapters that provide an in-depth review of each clinical phenotype, detailing current consensus diagnostic criteria and recent imaging and genetic findings. These chapters include an overview of FTD phenotypes (behavioral variant FTD [bvFTD]); primary progressive aphasia, including its nonfluent, semantic, and logopenic variants; the FTD–amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spectrum; and two other dementia conditions with cognitive changes that fall within the FTD spectrum (progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration). The clinical and pathological differences among the variants, especially the two most common (bvFTD and primary progressive aphasia), are clearly explained and, in many ways, confirm Pick’s hypothesis from 1892 that progressive brain atrophy can promote focal neuropsychiatric symptoms through specific, localized pathophysiology.

Section 3 explores diagnostic techniques for FTD. The broad clinical experience of the chapters’ authors is apparent in their discussions regarding clinical and neuropsychological assessment, brain imaging, CSF testing, and genetic counseling. Here the authors provide concrete advice on bedside cognitive assessment, specific neuropsychological testing relevant to each FTD phenotype, neuroimaging, CSF testing, and genetic testing. The well-illustrated neuroimaging chapter reviews all relevant techniques for FTD phenotypes: structural MRI, diffusion tensor imaging, resting state functional MRI, arterial spin labeling, single-photon emission computed tomography, and positron emission tomography (PET), including tau PET, which may help identify preclinical FTD. Imaging findings by genotype are also presented. The genetic counseling chapter lends a compassionate focus on the patient and the patient’s family, supplemented with case illustrations.

Section 4, on pathophysiology, begins with a summary chapter followed by detailed pathological findings for the phenotypes and genotypes, a review of Mendelian genetic findings, and a review of animal models in FTD research. This section does a remarkable job in demonstrating the pathological and genetic heterogeneity of FTD, showing both the progress that has been made in identifying the most common genetic correlates and major pathological proteins and the work focused on using this information to guide diagnosis and treatment that lies ahead.

The final section, drawing on the considerable experience of the chapter authors, emphasizes the importance of treating the patient over treating the disease. The section begins with a review of disability in FTD and is accompanied by detailed charts listing specific rehabilitation interventions for each aspect of FTD phenotypes, and there is also practical pharmacological and nonpharmacological intervention strategies for each disease stage. The rehabilitation suggestions alone make this book a valuable resource. The book concludes with a chapter on the family’s experience of having a loved one with FTD while further emphasizing the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to management. Although there is no specific chapter dedicated to psychopathology or psychiatric symptoms in FTD, information on these types of symptoms is included in the relevant clinical sections and is not difficult to find.

Editor Bradford Dickerson has done an admirable job of synthesizing a complex and rapidly growing literature into a digestible, cohesive framework, with consistent chapter structure that makes the book approachable and user friendly. Although it is difficult to know how many cases of FTD are missed by clinicians unfamiliar with its clinical manifestations, readers of this book will emerge with heightened diagnostic sophistication and confidence in initiating disease management. Psychiatrists, neurologists, primary care physicians, neuropsychologists, and nurse practitioners will find this volume a useful addition to their clinical library.