After more than two decades of increasing prevalence of prescription opioid use disorder in the United States (

1,

2), the number of people in the U.S. population with prescription opioid use disorders reached 2 million in 2015 (

3). Rising rates of prescription opioid use disorder have coincided with the largest epidemic of opioid overdose deaths in U.S. history. In 2015, unintentional drug overdose deaths, most of which involved opioids, claimed over 47,000 lives (

4). The crisis in nonmedical use of prescription opioids, which has exacted a heavy burden not only on individuals but also on their families and communities, has prompted federal policy makers to consider prescription opioid use disorder a threat to public health (

5).

In the wake of rising rates of nonmedical prescription opioid use, there has been increased public (

6) and professional (

7) interest in the possibility that cannabis might help to curb or prevent opioid use disorder. Support comes from two widely publicized ecological analyses indicating that compared with states that do not permit medical marijuana, annual death rates due to opioid overdoses were nearly one-quarter lower in states that do permit medical marijuana (

8,

9). Significant reductions in opioid prescribing have also been reported following passage of medical marijuana laws (

10). Such ecologic analyses, however, provide no information on whether individual patients who use cannabis have a lower or higher risk of developing opioid use disorders (

11).

The possibility that cannabis lowers the risk of opioid-related morbidity has fueled speculation concerning potential mechanisms. A leading hypothesis is that cannabis use tends to lower opioid use and risk of opioid use disorder through increased control of pain (

8,

12). A recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials provides a moderate level of evidence that cannabinoids improve some forms of chronic pain (

13). A large Dutch study reported that just over half of adults in registered cannabis programs also received prescriptions for pain medications, suggesting that medical marijuana is frequently used for pain control (

14). In a small, uncontrolled cross-sectional survey of medical marijuana users with chronic pain recruited from a cannabis dispensary, cannabis use was associated with a 64% decline in opioid use (N=118) (

12). Cannabis exposure has also been associated with increased analgesia among opioid-treated patients with chronic pain (

15), suggesting that cannabis may potentiate antinociceptive effects of opioids, permitting lower and presumably safer opioid dosing to achieve comparable analgesia.

Much remains to be learned about the association between cannabis use and nonmedical prescription opioid use or opioid use disorders. No prospective epidemiological or clinical studies have demonstrated that cannabis use reduces use of opioids. Moreover, epidemiologic research suggests that cannabis may actually

increase the risk of other drug use disorders, including opioids. A retrospective Australian twin study reported that early initiation of cannabis use was associated with increased risks of other drug use and abuse/dependence, including opioid use and opioid abuse/dependence (

16). Prospective epidemiological research further suggests that cannabis use is a risk factor for other drug use disorders (

17). However, prospective epidemiological research has not previously examined the specific association between cannabis use and nonmedical prescription opioid use or opioid use disorder to inform clinical practice and policy.

We sought to address this critical gap in knowledge with prospective data from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a large, nationally representative sample. We examined the association between cannabis use and incident nonmedical prescription opioid use and disorder 3 years later, after adjusting for several relevant demographic and clinical covariates. We also evaluated whether cannabis use among adults with nonmedical prescription opioid use was associated with a subsequent decrease in nonmedical opioid use.

Discussion

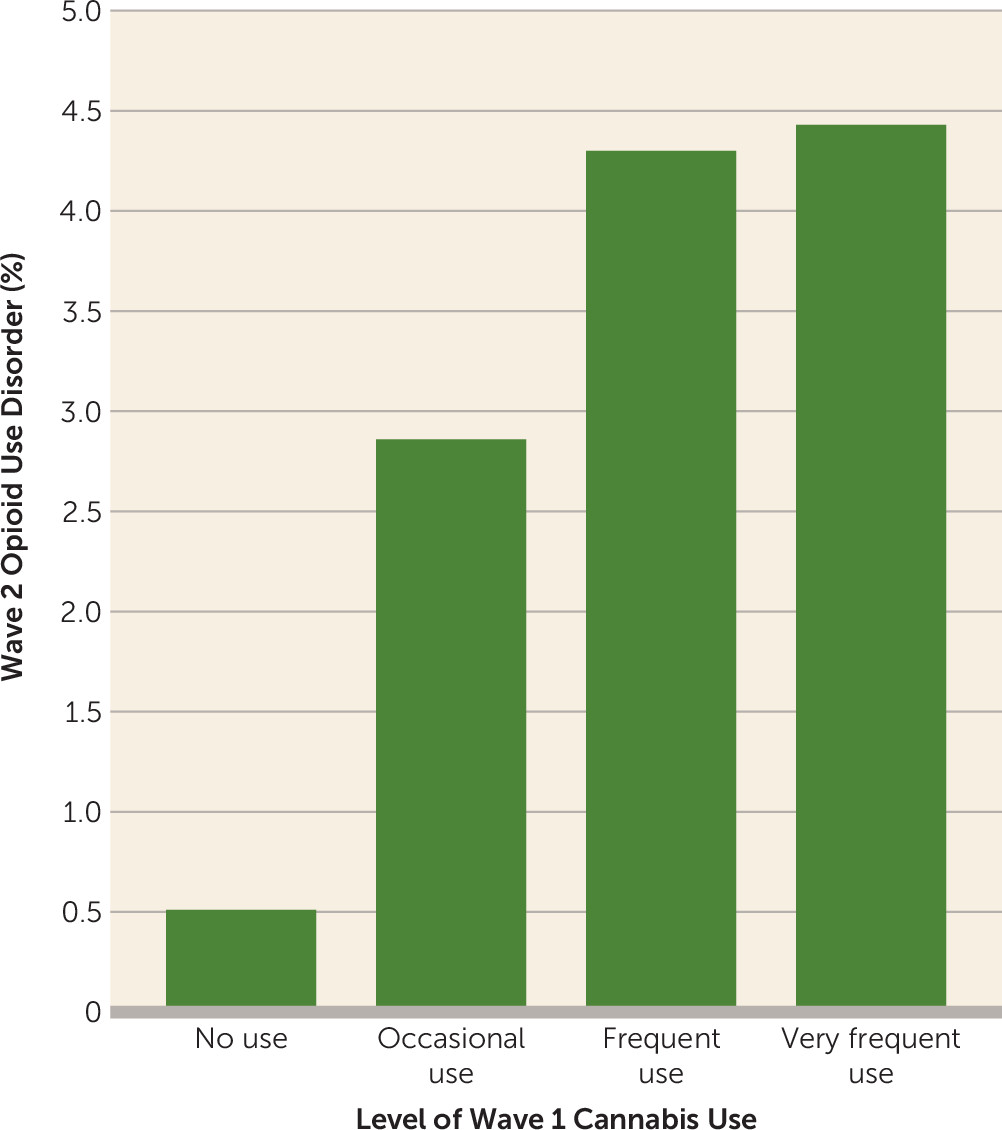

In a nationally representative sample of adults evaluated at waves 3 years apart, cannabis use was strongly associated with subsequent onset of nonmedical prescription opioid use and opioid use disorder. These results remained robust after controlling for the potentially confounding effects of several demographic and clinical covariates that were strongly associated with cannabis use. The association of cannabis use with the development of nonmedical opioid use was evident among adults without cannabis use disorders and among adults with moderate or more severe pain. Among adults with nonmedical prescription opioid use, cannabis use was associated with an increase in the level of nonmedical prescription opioid use at follow-up.

An independent prospective association between cannabis use and onset of prescription opioid use disorder extends results from previous epidemiological research concerning a link between cannabis use and other forms of problematic drug use (

15–

17). Previous work in this area has either been retrospective in design (

15) or focused on general associations between cannabis use and substance use disorders (

17) or problems (

16) rather than specifically nonmedical opioid use or opioid use disorder. Because in the present study the association was observed among adults with less than disorder-level of cannabis use and followed a dose-response pattern, it suggests that some increased risk extends to a relatively large population of adult cannabis users. If cannabis use tends to increase opioid use, it is possible that the recent increase in cannabis use (

30) may have worsened the opioid crisis.

Several factors may contribute to a tendency for individuals with cannabis use to develop opioid use disorder or increase the frequency of opioid use among opioid users. Heroin and Δ

9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ

9-THC) have similar effects on dopamine transmission through the μ

1 opioid receptor (

31). As compared with controls, adolescent rats exposed to Δ

9-THC have been shown to develop enhanced heroin self-administration as adults (

32). Also in relation to controls, rats exposed to Δ

9-THC have been found to have a greater behavioral response to morphine challenge (

33). These results are consistent with cross-sensitization between cannabis and opioids. In clinical research, cannabis use can lead to behavioral disinhibition, which can increase the risk of using other substances, including opioids (

34). Access to cannabis may also provide increased availability and social exposure to other drugs of abuse through peer affiliations (

35), although such environmental influences may be less powerful in recent years with increased prevalence of cannabis use and changing public attitudes.

Ecological studies reporting fewer opioid-related deaths (

8,

9) and decreased opioid prescribing following passage of medical marijuana laws (

10) have been interpreted in the media (

6) and scientific literature (

7) as supporting cannabis as a means of reducing opioid use disorder. Yet drawing inferences about the behavior of individuals from aggregated data can be misleading. It is possible, for example, that passage of medical marijuana laws increased local clinical awareness of opioid misuse, leading to earlier detection of high-risk patients or more cautious opioid prescribing practices. At the individual level, cannabis use appears to substantially increase the risk of nonmedical opioid use. Moreover, the general association between cannabis use and subsequent use of illicit drugs is not explained by the legal status of cannabis. An association of early cannabis use with increased subsequent risk of other drug abuse has been reported in prospective co-twin studies in Australia (

15), which has restrictive cannabis laws, and in the Netherlands, where cannabis is readily available (

36).

In accord with previous studies, several demographic and clinical covariates were associated with cannabis use (

17). These findings converge to highlight the wide range of factors that may influence initiation of cannabis. However, because cannabis use was not associated with significant pain at baseline, relief from pain does not appear to be a strong determinant of cannabis use in the general U.S. adult population, although we have no means of evaluating the analgesic effects of cannabis with NESARC data.

This study has several limitations. First, the NESARC sampled individuals age 18 and older. The relationship between cannabis and opioid use may differ in younger individuals (

16). Second, information on cannabis and opioid use was based on self-report and was not confirmed with urine toxicology, which may have led to underestimates. Third, the analysis was limited to two time points 3 years apart, which may have been too short an interval to observe delayed consequences of cannabis use on later risk of opioid use. Fourth, the data were collected over a decade ago, and the social context of cannabis use may have changed during this period (

30). Nevertheless, the NESARC remains the most recent nationally representative prospective cohort of U.S. adults with detailed information on substance use. Fifth, we were unable to distinguish recreational from medical marijuana use. However, typical medical marijuana participants have been reported to be young males with a history of recreational cannabis use (

37), and adults often combine medical and nonmedical cannabis use (

38). Sixth, some of the associations are based on a small number of individuals and should therefore be interpreted with appropriate caution. Seventh, the NESARC did not assess inmate populations, which may have a high prevalence of substance use disorders (

39). Finally, the assessment of nonmedical use of prescription opioids, although extensive, was not exhaustive and included two nonopioid medications (celecoxib and rofecoxib).

A long-standing controversy in drug research and policy concerns the extent to which use of cannabis predisposes to subsequent use of opioids and other drugs of abuse. We report that cannabis use, even among adults with moderate to severe pain, was associated with a substantially increased risk of nonmedical prescription opioid use at 3-year follow-up. Although the great majority of adults who used cannabis did not go on to initiate or increase their nonmedical opioid use, a strong prospective association between cannabis and opioid use disorder should nevertheless sound a note of caution in ongoing policy discussions concerning cannabis and in clinical debate over authorization of medical marijuana to reduce nonmedical use of prescription opioids and fatal opioid overdoses.