Such active substances as wine, opium, and other narcotics … possess a like property of effecting, when habitually indulged in to excess, a progressive change in the general system favorable to insanity … It appears, therefore, that intoxication may emulate almost every species of madness…; were the temporary state arising from intoxication to remain, after the immediate operation of the liquor had ceased, it would no longer be intoxication, but insanity. And this sometimes actually happens (

1, pp. 243–246).

—Thomas Arnold (1742–1816)

Substance-induced psychotic disorders have, as indicated by the above quotation, long been a focus of clinical and research interest in psychiatry. Kraepelin described, more than a century after Arnold, cases of alcoholic paranoia and hallucinosis and cocaine-induced delusional insanity, the latter often demonstrating bizarre schizophrenia-like delusions and passivity experiences (

2,

3), and Connell described amphetamine-induced psychosis in his classic 1958 monograph (

4). Kraepelin noted that although most patients recover quickly from cocaine-induced delusional insanity, delusions could persist long after cessation of use (

2, p. 144). More systematic modern studies suggest that an appreciable proportion of individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder go on to develop schizophrenia (

5–

8), with the best evidence coming from follow-up studies of epidemiological cohorts in Finland (

9) and Scotland (

10).

Clarifying the etiology of substance-induced psychotic disorder is of interest because it can provide insights generalizable to other psychotic syndromes (

11). Two etiologic questions are paramount. First, does the emergence of psychotic symptoms result solely from the pharmacological effects of the drug of abuse or also from the individual’s vulnerability to psychosis? Given the strong influence of familial and/or genetic factors in nonaffective psychoses (

12,

13), this question could be addressed by examining familial liability to nonaffective psychosis in individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder. If the psychosis resulted solely from drug exposure, familial risk for nonaffective psychosis would not be elevated in individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder. If, however, a psychotic diathesis played an important role in the emergence of the disorder, then such individuals would be expected to have an elevated familial liability to nonaffective psychosis.

Second, what is the etiology of schizophrenia that emerges after substance-induced psychotic disorder? Such cases could arise from 1) sustained pharmacologic exposure to drugs of abuse, 2) a mixture of drug exposure and modest individual liability to psychosis, or 3) a strong genetic diathesis where illness is simply precipitated by drug abuse. These three hypotheses predict, respectively, that the familial risk for nonaffective psychosis in individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder who develop schizophrenia should 1) not differ from control subjects, 2) have familial risk scores between those seen in healthy controls and typical individuals with schizophrenia, and 3) not differ from familial risk scores seen in typical individuals with schizophrenia.

Our analyses focused on three major questions. First, could we, using data from the Swedish national registries, obtain descriptive results for substance-induced psychotic disorder and its potential progression to schizophrenia, in line with the two previous registry-based longitudinal studies (

9,

10)? Second, could we clarify how familial risk scores, calculated from first-, second-, and third-degree relatives for nonaffective psychosis, drug abuse, and alcohol use disorder, distinguish those who develop substance-induced psychotic disorder from the general population and, among those who develop the disorder, distinguish between those who do compared with those who do not progress to schizophrenia? Third, could we develop a risk calculator from available data to predict development of schizophrenia in individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder?

Methods

In this prospective cohort study, we used several Swedish population-based registries with national coverage that were linked using each person’s unique identification number. To preserve confidentiality, this number was replaced by a serial number. We secured ethical approval for the study from the Regional Ethical Review Board of Lund University (no. 2008/409). All procedures complied with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

From the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register (national coverage between 1987 and 2015), the Outpatient Care Register (national coverage between 2001 and 2015), and the Primary Care Registry (based on primary health care visits in 18 county councils in Sweden with partial coverage from 1997 and onward), all of which used ICD-10 codes during these periods, we selected all individuals with a registration of substance-induced psychotic disorder defined with the following ICD codes: F10.5 (caused by alcohol), F11.5 (opioids), F12.5 (cannabis), F13.5 (hypnotics), F14.5 (cocaine), F15.5 (other stimulants), F16.5 (hallucinogens), F17.5 (tobacco), F18.5 (volatile solvents), and F19.5 (multiple/other drug use) between January 1, 1997, and December 31, 2015. We required that the individual be born in Sweden and have a first substance-induced psychotic disorder registration between ages 15 and 50. We included registrations for schizophrenia during the follow-up period, which extended from the date of substance-induced psychotic disorder registration until death, emigration, or end of study follow-up (December 31, 2015). Individuals with a registration of nonaffective psychosis prior to their substance-induced psychotic disorder were excluded from the sample. Schizophrenia was defined by the following ICD codes in the medical registers: ICD-10: F20.0, F20.1, F20.2, F20.3, F20.5, F20.9; ICD-9: 295.1, 295.2, 295.3, 295.6, 295.9; and ICD-8: 295.1, 295.2, 295.3, 295.6, 295.9. Nonaffective psychosis was defined in the same registers by the following ICD codes: ICD-10: F20, F22, F23, F24, F25, F28, F29; ICD-9: 295, 297, 298.3, 298.9; and ICD-8: 295, 297, 298.3, 298.9. For all individuals in the sample, we also included information on alcohol use disorder registrations, drug abuse registrations, and assignment of early retirement by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (for definitions, see the online supplement).

Using the Swedish Multi-Generation Register, we used data on first-, second-, and third-degree relatives (for details, see the

online supplement) to calculate a familial risk score for nonaffective psychosis. For our main analyses, we used Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to examine the cumulative hazard for schizophrenia for the different substance-induced psychotic disorder types. For comparison of familial risk scores between different groups, we used a nonparametric approach—van der Waerden scores (

14)—which ranks all values (the familial risk scores in the two groups) and then standardizes them (a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1). Next, we performed a Cox regression analysis with time to schizophrenia as outcome. As exposure variables, we used the different types of substance-induced psychotic disorders (with alcohol-induced psychosis as reference); the setting where the diagnosis of substance-induced psychotic disorder was made (primary care, outpatient specialist care, or inpatient care); and registrations for drug abuse, alcohol use disorder, or substance-induced psychotic disorder after the initial episode of substance-induced psychotic disorder. Among individuals registered in inpatient care, we constructed a separate model that also included length of hospitalization. In all models, we controlled for sex and age at registration for substance-induced psychotic disorder. Finally, we fitted a multivariate logistic regression model to a random half of the individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder as a training sample and then applied the results from that model to the second random half as a test sample. We divided the test sample into 10 risk groups and fitted a Cox regression model with time to schizophrenia as outcome and the 10 risk groups as exposure variables. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (

15).

Results

Table 1 summarizes the basic demographic and clinical characteristics of the 7,606 individuals born in Sweden between 1940 and 1995 who had a registration of substance-induced psychotic disorder between 1997 and 2015 and no prior recorded diagnosis of nonaffective psychosis as well as for the four forms of substance-induced psychotic disorder for which there were more than 1,000 individual registrations: alcohol, cannabis, stimulants, and multiple/other. The group was predominantly male (78%) with a mean age of 32.1 years at first registration for substance-induced psychotic disorder. The mean length of follow-up was 84 months. Substance-induced psychotic disorder registrations occurred most frequently in hospitals (59.5%) and outpatient specialty care settings (23.9%).

Before their first substance-induced psychotic disorder registration, 63% and 52% of the sample had been previously registered for drug abuse and alcohol use disorder, respectively. The mean age at registration for substance-induced psychotic disorder was earliest for cannabis (25.2 years) and latest for alcohol (39.4 years).

A total of 445 individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder received one or more diagnoses of schizophrenia during our follow-up. Of these, 314 (70.6%) had two or more schizophrenia diagnoses. The cumulative hazard for conversion to schizophrenia among individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder was 11.3% (95% CI=10.0, 12.8). Controlling for sex and year of birth, a diagnosis of substance-induced psychotic disorder carried a strong risk for a subsequent diagnosis of schizophrenia (hazard ratio=118.3, 95% CI=104.7, 133.7).

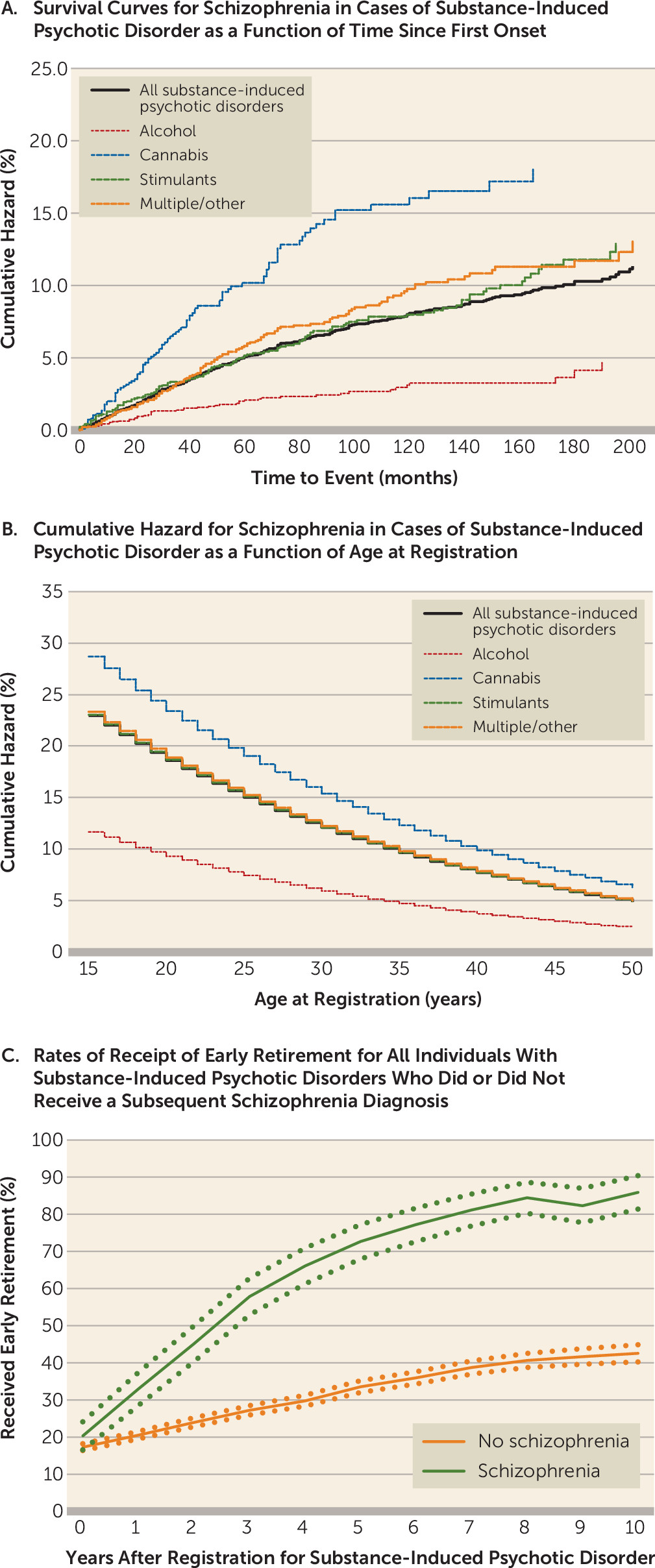

We examined the individual forms of substance-induced psychotic disorder and found that the cumulative hazard for schizophrenia was lowest for alcohol (4.7%, 95% CI=3.1, 7.1) and highest for cannabis (18.0%, 95% CI=14.5, 22.3). The cumulative hazards for schizophrenia onset for the four substance-induced psychotic disorder classes are illustrated in

Figure 1A. Because of differences in age at onset of substance-induced psychotic disorder across substance classes, we also examined the hazard ratio for schizophrenia, controlling for age at registration (

Figure 1B). A higher risk for schizophrenia onset for cannabis-induced psychosis was seen at all ages.

The mean time to schizophrenia conversion was 39 months. During the period between their first diagnosis of substance-induced psychotic disorder and first diagnosis of schizophrenia, individuals who developed schizophrenia had a mean of 2.86 drug abuse and 2.24 alcohol use disorder registrations. We examined the correlations between our three familial risk scores in the general population, which were as follows: drug abuse and alcohol use disorder, 0.34; drug abuse and nonaffective psychosis, 0.10; and alcohol use disorder and nonaffective psychosis, 0.09.

We evaluated differences in occupational competence between individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder who received a subsequent schizophrenia diagnosis and those who did not by examining rates of receipt of early retirement in the 10 years after the initial diagnosis of substance-induced psychotic disorder (

Figure 1C). Such status is awarded by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency to individuals whose work capacity is judged to be substantially reduced for a long-term period or permanently. The rates differed significantly within a year of the first substance-induced psychotic disorder diagnosis and diverged further over the subsequent decade.

Familial Risk Scores and Prediction of Substance-Induced Psychotic Disorder

As seen in

Table 2 (upper half), the standardized familial risk scores for drug abuse, alcohol use disorder, and nonaffective psychosis were significantly increased for all individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder. The elevation in familial risk score was greatest for drug abuse (mean standardized score, +1.09) and was significantly greater than the elevation for individuals in the general population with drug abuse but no substance-induced psychotic disorder (+0.82) (p<0.0001) (

Table 3). The elevation in familial risk score for alcohol use disorder in individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder was slightly lower (+0.98) but also significantly greater than that seen in individuals in the general population with alcohol use disorder but no substance-induced psychotic disorder (0.53) (p<0.0001). The mean elevation in familial risk score for nonaffective psychosis in individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder was more modest (+0.35) and significantly lower than that seen in individuals in the general population with schizophrenia but no substance-induced psychotic disorder (+0.77) (p<0.0001).

These scores differed significantly across the four common forms of substance-induced psychotic disorder that we studied. Individuals with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder and those with multiple/other substance–induced psychotic disorder had, respectively, the lowest and the highest familial risk for drug abuse. Individuals with cannabis-induced psychotic disorder and those with stimulant-induced psychotic disorder had, respectively, the lowest and the highest familial risk for alcohol use disorder. Individuals with alcohol- and cannabis-induced psychotic disorder had, respectively, the lowest and highest familial risk for nonaffective psychosis.

Predictors of Conversion to Schizophrenia

We first examined three nonfamilial risk factors for conversion to schizophrenia: the setting where the diagnosis of substance-induced psychotic disorder diagnosis was made, length of hospitalization among those hospitalized, and registrations for drug abuse, alcohol use disorder, or substance-induced psychotic disorder after the initial psychotic disorder episode. All these variables significantly predicted risk for subsequent schizophrenia after controlling for sex and age at registration of substance-induced psychotic disorder. Compared with registration occurring in a primary care setting, the hazard ratio for schizophrenia was 2.06 (95% CI=1.13, 3.76) for diagnosis in a specialist care setting and 2.77 (95% CI=1.57, 4.88) for diagnosis in a hospital. Among individuals hospitalized for substance-induced psychotic disorder (N=4,553), compared with those hospitalized for only 1 day, the hazard ratios for developing schizophrenia for those hospitalized for 2–3 days, 4–7 days, and ≥8 days were 0.87 (95% CI=0.62, 1.21), 1.00 (95% CI=0.71, 1.39), and 2.21 (95% CI=1.70, 2.87), respectively. Finally, risk for conversion to schizophrenia was increased by an additional registration, after the first substance-induced psychotic disorder diagnosis, for drug abuse (hazard ratio=1.60; 95% CI=1.27, 2.02), alcohol use disorder (hazard ratio=1.36; 95% CI=1.11, 2.65), or substance-induced psychotic disorder (hazard ratio=2.86; 95% CI=2.35, 3.47).

We then compared the standardized familial risk (

Table 2, lower half) for drug abuse, alcohol use disorder, and nonaffective psychosis among individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder who progressed to schizophrenia with those who did not. While these two groups did not differ significantly in their familial risk scores for drug abuse or alcohol use disorder, the familial risk scores for patients who converted to schizophrenia were twice as high (+0.67) as for those who did not develop schizophrenia (+0.33) (p<0.0001). No significant differences were seen in the familial risk scores for psychosis across the four forms of substance-induced psychotic disorder that we studied.

Table 3 provides a comparison, in the general population, of our familial risk scores for all cases of drug abuse, alcohol use disorder, and schizophrenia, with and without substance-induced psychotic disorder. Compared to individuals with drug abuse but without substance-induced psychotic disorder, those with drug abuse and substance-induced psychotic disorder had 15% and 68% elevations in their familial risk scores for drug abuse and alcohol use disorder and a 300% increased risk for nonaffective psychosis (all p<0.0001). Compared with individuals with alcohol use disorder but no substance-induced psychotic disorder, those with alcohol use disorder and substance-induced psychotic disorder had 180% and 75% elevations in their familial risk scores for drug abuse and alcohol use disorder and a 244% increased risk for nonaffective psychosis (all p values <0.0001).

Compared with individuals with schizophrenia but without substance-induced psychotic disorder, those with substance-induced psychotic disorder that developed into schizophrenia had significantly elevated familial risk scores for drug abuse and alcohol use disorder, but their risk scores for nonaffective psychosis did not significantly differ. In particular, the mean familial risk scores for nonaffective psychosis for individuals with alcohol-, cannabis-, and stimulant-induced psychotic disorder that developed into schizophrenia (respectively, +0.81, +0.79, and +0.78) are nearly identical to the observed mean familial risk scores for individuals with schizophrenia without substance-induced psychotic disorder (+0.77).

Development of a Risk Calculator

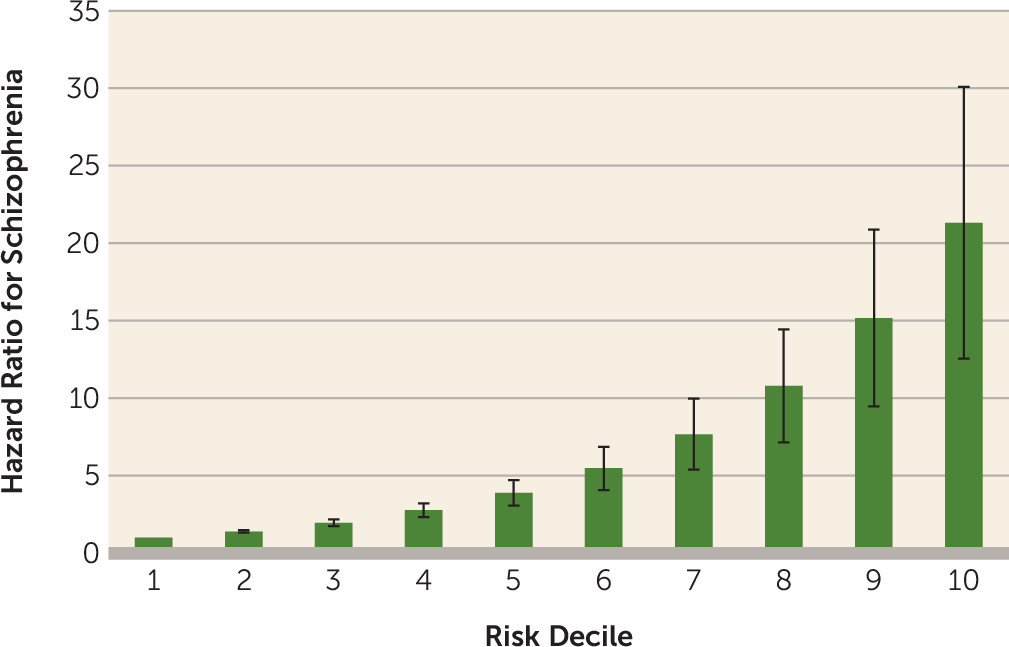

We fitted a multivariate regression model to a random half of the cohort as a training sample, including the setting where the diagnosis of substance-induced psychotic disorder was made; registrations for drug abuse, alcohol use disorder, or substance-induced psychotic disorder after the initial episode of substance-induced psychotic disorder; additional registrations for substance-induced psychotic disorder after the initial diagnosis; familial risk scores for drug abuse, nonaffective psychosis, and alcohol use disorder; age at registration for substance-induced psychotic disorder; sex; and type of substance-induced psychotic disorder. Results from that model were then applied to the second random half as the test sample. After dividing our sample into deciles, we obtained a hazard ratio for schizophrenia outcome per decile of 1.40 (95% CI=1.32, 1.49). The uniquely significant predictors in this model were male sex, early age at first registration, high familial risk score for nonaffective psychosis, first diagnosis taking place in a specialist or an inpatient care setting, and additional substance-induced psychotic disorder diagnoses.

Figure 2 displays the hazard ratios for these deciles compared with the lowest risk group. Compared with the first decile, individuals in the ninth and 10th deciles of risk had hazard ratios of 15.2 (95% CI=9.5, 24.3) and 21.3 (95% CI=12.6, 36.2), respectively. A receiver operating curve analysis provided an area under the curve of 0.74 (95% CI=0.71, 0.77) (see Figure S1 in the

online supplement).

Discussion

We had three major goals for this study. The first was to determine how well results in Sweden replicated the results of two previous longitudinal cohort studies of substance-induced psychotic disorder, from Finland and Scotland (

9,

10). Rates of conversion to schizophrenia differed widely (11.3% in this study, 17.3% in Scotland, and 46% in Finland), but much of this variation likely resulted from differences in follow-up time and breadth of definition, which varied from schizophrenia spectrum disorder in the Finland study to narrowly defined schizophrenia in our study. These three samples also produced a range of more convergent findings, including 1) alcohol-induced psychotic disorder having the latest age at onset of any substance-induced psychotic disorder type and the lowest conversion rate to schizophrenia; 2) cannabis-induced psychotic disorder having one of the lowest ages at onset and the highest conversion rate to schizophrenia; 3) male sex and younger age at diagnosis of substance-induced psychotic disorder predicting higher risk of conversion to schizophrenia; and 4) shorter hospitalizations for substance-induced psychotic disorder predicting lower risk of conversion to schizophrenia.

Our second goal was to use information about familial risk score to evaluate etiologic hypotheses about who develops substance-induced psychotic disorder and who then progresses to schizophrenia. Focusing first on substance-induced psychotic disorder, we could confidently reject the hypothesis that the disorder arises solely from the psychotogenic effects of the substances of abuse. Individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder had, on average, one-third of a standard deviation higher familial risk score for nonaffective psychosis than the general population—a highly significant difference. Our findings are congruent with previous evidence that among methamphetamine users, the risk for schizophrenia, assessed by family history, was significantly higher in those who developed methamphetamine-induced psychosis compared with those who did not (

16).

Our results, however, also support an effect of substances of abuse on substance-induced psychotic disorder. The mean familial risk scores for nonaffective psychosis differed significantly across our drug classes and were lowest for those who developed alcohol-induced psychotic disorder. Compared with the other substances studied, the psychotic symptoms emerging from heavy drinking are more likely to be influenced by direct pharmacologic effects and less by the individual’s liability to psychosis. Our analyses also clarify the impact of familial risks for drug abuse and alcohol use disorder on substance-induced psychotic disorder. Individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder had considerably higher familial risk for drug abuse and alcohol use disorder than they did for psychosis. Finally, the mean familial risk scores for drug abuse and alcohol use disorder in our cohort of individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder were higher than those seen in individuals with drug abuse or alcohol use disorder without substance-induced psychotic disorder. Thus, an elevated familial risk for drug abuse and alcohol use disorder plays an important etiologic role in substance-induced psychotic disorder.

Turning to the conversion of substance-induced psychotic disorder to schizophrenia, we also obtained clear results. Familial risk for drug abuse or alcohol use disorder had no impact on risk for schizophrenia in substance-induced psychotic disorder; the mean familial risk scores for drug and alcohol abuse did not differ among those with substance-induced psychotic disorder who progressed to schizophrenia compared with those who did not. However, familial risk scores for nonaffective psychosis were twice as high in those with substance-induced psychotic disorder who later received a schizophrenia diagnosis compared with those who did not. Finally, across all our cases, mean familial risk score for nonaffective psychosis did not differ between individuals with schizophrenia who had a previous substance-induced psychotic disorder diagnosis and those who did not. That is, with respect to familial risk for psychosis, patients with substance-induced psychotic disorder who develop schizophrenia are indistinguishable from patients with schizophrenia without a history of substance-induced psychotic disorder. These results support the hypothesis that in substance-induced psychotic disorder, drugs of abuse may precipitate the development of schizophrenia but do not typically have a strong causal role in the emergence of the chronic psychosis. If drug exposure caused the schizophrenia disorder, such affected individuals should, on average, have lower familial psychosis risk than typical individuals with schizophrenia, which they do not. Our findings are consistent with those reported by Tsuang et al. (

17), who found that risk for schizophrenia in the first-degree relatives of individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder closely resembled that observed in the relatives of a group of typical probands with schizophrenia.

We were able to validate our diagnostic results by comparing them with data on receipt of early retirement benefits among individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder. Individuals subsequently diagnosed with schizophrenia were twice as likely as those without the diagnosis to receive such benefits, and this difference emerged quite early in the course of their post-substance-induced psychotic disorder, in many cases before they received their schizophrenia diagnosis.

Our third goal was to develop a risk calculator to predict progression of substance-induced psychotic disorder to schizophrenia. We generated and then tested our model on random split-halves of our sample. The predictive power of our model was substantial; 47% of individuals who converted from substance-induced psychotic disorder to schizophrenia were found to be in the upper two deciles of risk, and our area under the curve results (74%) were substantial.

What can we learn from our analyses about the nature of the cannabis-schizophrenia association (

6,

18)? Cannabis-induced psychotic disorder stood out from the other forms in having the earliest age at onset, the highest risk for conversion to schizophrenia, and the highest familial risk for psychosis. Individuals with cannabis-induced psychotic disorder who developed schizophrenia had the same familial risk for schizophrenia as typical individuals with schizophrenia. In our multivariate prediction model, where familial risk scores for nonaffective psychosis were controlled for, cannabis use no longer predicted an elevated risk for conversion to schizophrenia. Our results suggest that the high conversion rate to schizophrenia in cannabis-induced psychosis is at least in part a result of high familial risk for nonaffective psychosis rather than solely a result of the pharmacological effects of cannabis. Our findings do not directly contradict claims for a causal relationship between heavy cannabis exposure and schizophrenia (

18). However, in accord with our previous findings from a co-relative study of cannabis abuse and schizophrenia in a Swedish national study (

19), our results suggest that the observed association between cannabis abuse and schizophrenia is not entirely causal but results in part from some sharing of familial/genetic risk for cannabis abuse and schizophrenia (

19).

Our results should be interpreted in the context of four potential methodological limitations. First, our findings are applicable only to the Swedish population and may or may not extrapolate to other countries. Second, although ascertaining cases of drug abuse, alcohol use disorder, and schizophrenia from registry data has important advantages, especially independence from subject cooperation and accurate recall, it also may have significant limitations. For drug abuse and alcohol use disorder, there are surely false negatives for individuals who abuse substances but avoid medical or police attention. However, the validity of our detection of these syndromes is supported by evidence for strong associations among cases detected in different registries. The mean odds ratio for case detection across our relevant registries was 52 for drug abuse (

20) and 33 for alcohol use disorder (

21). While diagnoses of schizophrenia were recorded by diverse clinicians, studies using record reviews (

22) and diagnostic interviews (

23) found that 96% and 94%, respectively, of individuals in Sweden with schizophrenia diagnosed in a hospital fulfilled DSM-IV criteria. Furthermore, our schizophrenia diagnoses were validated by showing strong associations with assignment of early retirement. Third, our analyses required only one schizophrenia diagnosis to consider an individual with substance-induced psychotic disorder a “converter” to schizophrenia. Because this may have been too weak a threshold, we repeated all our major analyses using a threshold of two separate diagnoses (see Figure S2 and Tables S1 and S2 in the

online supplement). The results did not change appreciably. Fourth, it is conceivable that the high conversion rate of cannabis-induced psychotic disorder to schizophrenia resulted from misdiagnosing cases of true schizophrenia as being cannabis-induced. If this were the case, however, then the individuals with cannabis-induced psychotic disorder should have had a higher rate of early disability than others with substance-induced psychotic disorder, and this result was not seen (see

Figure 1C; see also Figure S3 in the

online supplement).

Conclusions

Substance-induced psychotic disorder occurs in individuals with high familial liability to drug and alcohol abuse and a moderate familial vulnerability to psychosis (roughly midway between those seen in the general population and in schizophrenia). Thus, substance-induced psychotic disorder likely arises from both substantial drug exposure and elevated liability to psychosis. Only alcohol-induced psychotic disorder may differ in requiring less familial vulnerability to psychosis. A modest proportion of individuals with substance-induced psychotic disorder develop schizophrenia. The probability of this conversion can be predicted from a range of risk factors, including early age at first episode of substance-induced psychotic disorder, male sex, and further drug abuse, alcohol use disorder, or especially episodes of substance-induced psychotic disorder. Familial liability to psychosis, but not to substance abuse, strongly predicts this conversion. Indeed, the familial psychosis liability to typical schizophrenia and schizophrenia following substance-induced psychotic disorder are indistinguishable. Schizophrenia following substance-induced psychotic disorder is better explained as a drug-precipitated disorder in highly vulnerable individuals rather than as a syndrome predominantly caused by drug exposure.