Suicide is in a very marked and striking manner hereditary; and this is a strong ground for regarding it as constitutional… Dr. [Benjamin] Rush, M. Esquirol, and others have recorded instances of the hereditary transmission of this propensity. M. Falret has collected a variety of observations on the subject, and has concluded that, of all the kinds of insanity, the form distinguished by this tendency is probably that which the most frequently becomes hereditary (Prichard, 1837 [

1, p. 284]).

A long catalog could be given of all sorts of inherited … predisposition[s] to various diseases … [one example being that] several members of the same family, during three or four successive generations, have committed suicide (Darwin, 1868 [

2, p. 16]).

Psychiatry has long been interested in the familial transmission of suicidal behavior. Despite a substantial number of family and twin studies of both suicide attempt and death by suicide that have confirmed important familial and genetic contributions (

3–

5), we are aware of only two previous adoption studies specifically focused on death by suicide (

6,

7) and only one focusing on suicide attempt (

8). Schulsinger et al. (

6) examined only aggregated biological and adoptive relatives of adoptees who died by suicide, and Petersen et al. studied biological and adoptive siblings of adoptees who died by suicide (

7) and who had a history of suicide attempt (

8), respectively. To our knowledge, no previous study has examined rates of suicidal behaviors among the offspring of biological and adoptive parents who died by suicide and/or had a history of suicide attempt.

In this study, we explored the sources of cross-generational transmission of suicide attempt and suicide death. We utilized an expanded adoption design involving four family types: intact nuclear families, families with a not-lived-with biological father (who sired the child but never lived with or near his offspring), families with a stepfather, and adoptees and their biological and adoptive parents. From these four family types, we explored the resemblance for suicide attempt and suicide death among parents and offspring of parents who provided to their children both genes and rearing, genes only, or rearing only.

We began by asking three questions about suicide attempt:

1. What are the relative roles of genetic and rearing effects in the cross-generational transmission of suicide attempt?

2. Does parent-child transmission of suicide attempt differ as a function of the sex of the parent or the child?

3. What proportion of the cross-generational transmission of suicide attempt results from parental psychiatric or substance use disorders, and do these proportions differ across the types of parent-child relationships? We hypothesized that the contributions of these disorders to parent-child resemblance for suicide attempt will be stronger for genetic transmission than for rearing transmission.

Next, we examined two questions about suicide death:

1. What are the relative roles of genetic and rearing effects in the cross-generational transmission of suicide death?

2. What is the nature of the relationship between the transmitted genetic liability to suicide attempt and suicide death? What is their genetic correlation, and do suicide attempt and suicide death lie on a single dimension of genetic liability, with suicide attempt representing a milder form and suicide death a more severe form?

Methods

We collected information on individuals from Swedish population-based registers with national coverage linking each person’s unique personal identification number, which was replaced with a serial number by Statistics Sweden in order to preserve confidentiality. We utilized the following sources: the Multi-Generation Register, the Population and Housing Censuses, the Swedish Hospital Discharge Register (national coverage from 1987 to 2015 and partial coverage from 1969 to 1986), the Outpatient Care Register (national coverage from 2001 to 2015), and the Mortality Register (1969 to 2015). Ethical approval was obtained from the Lund University Regional Ethical Review Board.

Suicide attempt was identified in the Swedish National Patient Register Hospital Discharge/Outpatient (Specialist) Care Registry, and death by suicide was identified in the Mortality Registry using the following diagnostic codes: ICD-8/9: E95 and E98; ICD-10: X60–X89, Y10–Y34, Y87, Y90, and Y91. In the analysis of suicide attempt, individuals who died by suicide were excluded. We evaluated the hypothesis that suicide attempt and suicide death were disorders of differing severity on the same liability distribution in our largest sample of genetically informative parent-child correlations: not-lived-with fathers and their offspring.

The database was created by entering all individuals in the Swedish population born in Sweden from 1960 to 1990. The database also included the number of years (during ages 0–15) that individuals resided in the same household and geographical area as their biological mother, biological father, and stepfather when applicable. From 1960 to 1985, we used household identification from the Population and Housing Census to define family types available every fifth year, and thus there is a possibility that some errors in family assignment may have occurred. The household identification includes all individuals living in the same dwelling. For 1986 onward, we defined family type using the family identification from the Total Population Register, available yearly. The family identification is defined by related or married individuals registered at the same property. Additionally, adults registered at the same property who have common children but are not married are registered in the same family. We created family types by investigating with whom offspring shared the same household and family identification from ages 0 to 15. In the detection of stepparents during the period of 1986 onward for an offspring living with his or her mother, we included the stepfather only if he was married to the mother of the offspring and/or had a common child with her. For the years without this information, we approximated the household with the information from the closest year.

We thereby defined the following four family types: intact families (the offspring resided with the biological mother and father from ages 0 to 15), not-lived-with father families (the offspring never resided in the same household or near the biological father), stepfather families (the offspring did not reside with the biological father from ages 0 to 15 and during that age range resided ≥10 years with a nonbiologically related male 18 to 50 years older), and adoptive families (the offspring before age 5, with information available on both adoptive parents and at least one biological parent). Individuals who were adopted by biological relatives or an adoptive parent living with a biological parent were excluded. To maximize the number of adoptees, we included offspring born between 1955 and 1990. The not-lived-with fathers and stepfathers were delineated so that their relationship with the offspring maximally resembled that observed between an adoptee and his or her biological parent and adoptive parent, respectively.

We examined the tetrachoric correlation between all possible combinations of suicide attempt and suicide death in our parent-child pairs, because this measure of association is easy to interpret in genetic-epidemiologic terms (i.e., it equals the correlation of liability) and is insensitive to changes in base rates. We also report odds ratios for key results from logistic regression. In addition, we investigated sex-specific transmission for the suicide attempt to suicide attempt transmission.

Finally, we used a linear probability model to examine the degree to which the transmission of suicide attempt from parents to children resulted from the transmission of psychiatric illness. Because the base rates of suicide attempt were different in the four different family types, we opted for the linear probability model, where results are presented on the additive scale and are more comparable between family types. In the first model, we included suicide attempt in the parent, and in the second model we added occurrence in parents with major depression, anxiety disorders, drug abuse, alcohol use disorder, bipolar illness, and nonaffective psychosis (for a list of definitions, see the online supplement).

To combine results from the different samples, we used the Olkin-Pratt meta-analytical approach. We calculated the combined correlations and the p values for the heterogeneity tests that evaluated the null hypothesis that effects were similar across samples. We calculated the genetic correlation between suicide attempt and suicide death (see the

online supplement). Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (

9) and R, version 3.6.1 (

10).

Results

Sample and Results Presentation

Descriptive characteristics of the four family types (intact families, not-lived-with father families, stepfather families, and adoptive families) are presented in

Table 1. Intact families were the most common family type, followed by not-lived-with father families, stepfather families, and adoptive families. Suicide attempts were more common than suicide deaths among parents and offspring in all family types. Both forms of suicidal behavior were rarer among offspring and parents from intact families compared with other family types and less common among stepparents and adoptive parents compared with biological parents and not-lived-with fathers.

Separate results for all informative maternal-child and paternal-child correlations for both suicide attempt and suicide death and between suicide attempt and suicide death across the four family types are summarized in

Table 2. Comparison of results from the maternal-child and paternal-child relationships, including a weighted estimate (i.e., a parental-child correlation [

Figure 1]), is presented in

Table 3. Correlations across the four types of parent-child relationships (mother-daughter, mother-son, father-daughter, and father-son) are presented in

Table 4.

Transmission of Suicide Attempt

We report the tetrachoric correlation for suicide attempt to suicide attempt mother-offspring and father-offspring transmission across the four family types, as well as the weighted estimate across all informative families for parent-child pairs with a genes plus rearing relationship, genes-only relationship, or rearing-only relationship, including a heterogeneity test for these estimates (

Table 2). The estimates for mothers and fathers, their weighted estimates, and heterogeneity analyses are summarized in

Table 3.

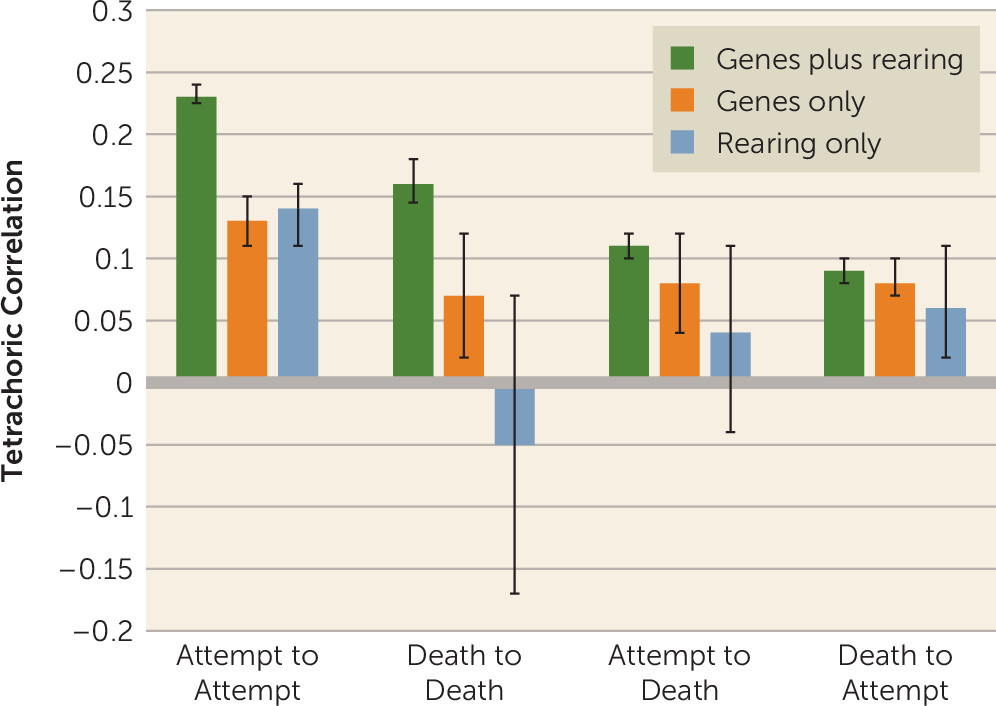

For suicide attempt to suicide attempt parent-child transmission, the overall estimates for genes plus rearing, genes-only, and rearing-only relationships were 0.23 (95% CI=0.23, 0.24), 0.13 (95% CI=0.11, 0.15), and 0.14 (95% CI=0.11, 0.16), respectively (

Figure 1). No heterogeneity of estimation was observed for genes-only and rearing-only relationships. For the genes plus rearing analyses, where larger samples were available, intersample statistical heterogeneity was observed, although the absolute difference in estimates was modest. The parallel odds ratios for these three associations were 3.28 (95% CI=3.21, 3.35), 1.76 (95% CI=1.66, 1.86), and 1.89 (95% CI=1.67, 2.13), respectively.

Effect of Sex on Suicide Attempt Transmission

Across the weighted estimates from the family types, we tested the heterogeneity of parent-child transmission of suicide attempt across mother-daughter, mother-son, father-daughter, and father-son pairs (

Table 4). Significant heterogeneity was found in genes plus rearing and genes-only relationships but not in the rearing-only relationship. To determine the origin of this heterogeneity, for both genes plus rearing and genes-only relationships, we compared the results for transmission to sons versus daughters and transmission from mothers versus fathers. In the genes plus rearing sample, both comparisons differed significantly. However, the difference was more significant and larger for transmission to sons versus daughters compared with from fathers versus mothers. For the genes-only relationship, the only significant difference was stronger transmission to sons than to daughters.

Effect of Psychiatric Illness on Cross-Generational Transmission

To examine the degree to which the transmission of suicide attempt from parents to children resulted from the transmission of psychiatric illness, we examined transmission of suicide attempt using a linear probability model across all family types and repeated these analyses controlling for the occurrence in parents with major depression, anxiety disorders, drug abuse, alcohol use disorder, bipolar illness, and nonaffective psychosis. We explored the degree to which the association for suicide attempt was attenuated by the addition of parental psychiatric disorders to the model. For the genes plus rearing relationship, the weighted raw and controlled betas were 6.14 (95% CI=6.04, 6.25) and 5.48 (95% CI=5.38, 5.59), respectively, producing a modest attenuation of 11% (

Figure 1). For the genes-only parent-child relationship, the parallel figures were 4.10 (95% CI=3.68, 4.52) and 2.48 (95% CI=2.02, 2.94), demonstrating a 40% attenuation. By contrast, for the rearing-only parent-child relationship, the parallel figures were 4.15 (95% CI=3.31, 4.98) and 4.18 (95% CI=3.31, 5.05), demonstrating no attenuation.

Transmission of Suicide Death

The tetrachoric correlations for suicide death to suicide death transmission in mother-offspring and father-offspring pairs are presented in

Table 2. For suicide death to suicide death parent-child transmission, the best estimates of the tetrachoric correlations across family types and mothers and fathers for the genes plus rearing, genes-only, and rearing-only parent-child relationships were 0.16 (95% CI=0.15, 0.18), 0.07 (95% CI=0.02, 0.12), and −0.05 (95% CI=−0.17, 0.07), respectively (

Figure 1). The latter two of these estimates were imprecisely known because of the rarity of suicide death. Modest statistical heterogeneity was found only for the genes plus rearing relationship, which was stronger for mother-child pairs compared with father-child pairs (

Table 2).

Transmission of Suicide Attempt to Suicide Death and Suicide Death to Suicide Attempt

Tetrachoric correlations for suicide attempt to suicide death transmission and suicide death to suicide attempt transmission from mothers and fathers to offspring across the four family types are presented in

Table 2. No statistical heterogeneity was detected across family types. When we compared the weighted estimates (

Table 3) in genes plus rearing analyses, the results were significantly stronger for mothers compared with fathers, but no differences were found for the genes-only and rearing-only relationships. Finally, we compared the aggregate estimates for suicide attempt to suicide death transmission and suicide death to suicide attempt transmission (

Table 3). For the genes plus rearing relationship, the estimate for the former was statistically greater than the estimate for the latter. Across family types, mothers and fathers, and suicide attempt to suicide death and suicide death to suicide attempt transmissions, the correlations for genes plus rearing, genes-only, and rearing-only parent-child relationships were 0.10 (95% CI=0.09, 0.11), 0.08 (95% CI=0.07, 0.09), and 0.06 (95% CI=0.02, 0.09), respectively.

From these results, the cross-generation genetic correlation of suicide attempt and suicide death was 0.84 (95% CI=0.74, 1.00), suggesting substantial sharing in the genetic risk factors for suicide attempt and suicide death. To test whether suicide attempt and suicide death were, from a genetic perspective, behaviors of differing severity on the same continuum of liability, we fitted a three-category multiple threshold model to results from not-lived-with fathers and their children that included no suicide attempt or suicide death, suicide attempt only, and suicide death only. The polychoric correlation was estimated at 0.13 (SE=0.01), close to that obtained for suicide attempt alone; however, the model fit poorly (χ2=40.26, df=3, p<0.001).

Discussion

We had five goals in this study. First, we sought to clarify the magnitude and nature of the cross-generational transmission of suicide attempt. We found substantial parent-child resemblance for suicide attempt estimated in intact families by a tetrachoric correlation and odds ratio of 0.23 and 3.28, respectively. Supporting the representativeness of our sample, this odds ratio is within the range from a meta-analysis of family studies of suicide attempt (odds ratio=2.77, 95% CI=2.22, 3.48) (

4). The cross-generational transmission of suicide attempt resulted, in nearly equal degrees, from genetic and rearing effects. Calculating heritability from an adoption study is straightforward, because it equals twice the tetrachoric correlations for genes-only parent-child relationships, here equaling 26% (95% CI=0.22, 0.30).

Our findings were internally consistent across multiple family samples, with one exception. Correlations from the mother-offspring genes plus rearing relationship in the not-lived-with father and stepfather families were moderately lower than that found in intact families. This introduced modest heterogeneity in the weighted average for the genes plus rearing relationship for mothers compared with fathers that was detectable as a result of our large sample sizes. The general similarity of our estimates for genes plus rearing, genes only, and rearing only across different family types (intact families, not-lived-with father families, stepfather families, and adoptive families) supports the assumptions underlying our extended adoption design.

While we are unaware of previous adoption studies of parent-child transmission of suicide attempt, Peterson et al. (

8) found marginally significant evidence of excess risk for suicide attempt in biological siblings of Danish adoptees with a history of suicide attempt. Our findings can also be usefully compared with those of three twin studies that examined self-reported suicide attempt (

11–

13). Estimates of the heritability of suicide attempt were variable and known imprecisely, ranging from 17% to 55%. Shared environment was estimated in two studies at 19% (

13) and 8% (

11).

Our second goal was to examine sex effects in the parent-child transmission of suicide attempt. We found such effects in genes plus rearing and genes-only relationships, and in both of these relationship types, the most prominent finding was that transmission was stronger to sons than to daughters. While there is a large literature on sex effects in suicidal behavior (

14), we have been unable to find previous comparable results.

Third, we sought to clarify the degree to which the parent-child transmission of suicide attempt resulted from the transmission of the liability to psychiatric and substance use disorders. Most importantly, in the genes-only parent-child relationship, adding six major psychiatric and substance use disorders to the model resulted in a 40% reduction in transmission of suicide attempt. This suggests that approximately two-fifths of the parent-child genetic resemblance for liability to suicide attempt can be accounted for by transmission of risk for psychiatric and substance use disorders. These findings are not congruent with those from the Danish sibling adoption study noted above, which found no reduction in resemblance for suicide attempt between adoptees and their biological siblings after controlling for psychiatric admissions (

8). However, a summary of twin studies of suicide attempt concluded that “the presence of genetic vulnerability to nonfatal suicidal behaviors cannot be fully explained by genetically influenced psychopathology” (

5, p. 266), and a similar conclusion was reached from family studies of suicide attempt (

3).

However, we found quite different results in our rearing-only parent-child pairs, where the addition of parental psychiatric and substance use disorders to the model produced no attenuation in the magnitude of transmission of suicide attempt. These results suggest qualitive differences in the nature of the risk for suicide attempt from parents who provide genes compared with those who only rear their offspring. For rearing-only parents, our results would be consistent with social learning as a prime mechanism for the cross-generational transmission of risk for suicide attempt (

15).

Our fourth goal was to examine the sources of parent-child resemblance for suicide death, a goal compromised by the rarity of suicide death in our study sample and the resulting low power of our analyses. Consistent with the two previous adoption studies of suicide death, which examined risk for suicide death in either all biological relatives of adoptees who died by suicide (

6) or their siblings only (

8), we found evidence of genetic transmission of risk for suicide death. However, the magnitude of the transmission, although imprecisely known, was smaller than that for suicide attempt. Our results are also consistent with a partial adoption study (

16), which examined resemblance for suicide death only between biological parents and their adopted-away offspring in an early Swedish adoptive cohort (born from 1946 to 1968 and thus overlapping by 14 years with our cohort members, born between 1955 and 1990) and reported a hazard ratio for suicide death that was slightly higher than the odds ratio obtained in our study.

Our direct estimates of rearing effects for suicide death were not statistically significant and were imprecisely known. However, rearing effects can also be indirectly assessed from the difference in the correlations estimated from genes plus rearing and genes-only relationships. For suicide death, this would be estimated at 0.09. In addition, there was weak evidence for rearing effects in our suicide attempt to suicide death analyses, with positive estimates that did not differ from zero. Overall, suicide death is too rare in these Swedish families for us to be confident about the sources of parent-child transmission. Genetic effects for suicide death clearly exist, but it remains uncertain whether cross-generational environmental effects exist.

Our final goal was to understand the relationship between the cross-generational genetic transmission of suicide attempt and suicide death. Adding to our information about the parent-child transmission of both suicide attempt and suicide death, we examined their cross-transmission—that is, from suicide attempt to suicide death and suicide death to suicide attempt. From the genetic correlations obtained from these four analyses, we could calculate a cross-generational genetic correlation between suicide attempt and suicide death. It was high (0.84) but short of unity. One way to identify why we found such a high correlation is to note that the genetic transmission from suicide attempt among parents to suicide death among offspring (0.08) was nearly the same as the genetic transmission from suicide death to suicide death (0.07). However, in not-lived-with fathers and their offspring, our study was well powered to test, from a genetic perspective, whether suicide attempt and suicide death could be assumed to reflect behaviors resulting from the same genetic liability, differing only in severity. We could reject this hypothesis, indicating important qualitative differences in the nature of the transmitted liability to suicide attempt and suicide death.

Limitations

These results should be interpreted in the context of four potentially important limitations. First, suicide attempt was ascertained from medical registries and likely represented, on average, more severe attempts than those obtained by self-report or interview-based methods. Approximately 40% of nonfatal suicide attempts do not involve medical attention (

17). Second, the quality of the diagnosis of death by suicide needs to be considered. In Sweden, unexpected deaths occurring outside of hospitals are all investigated through a forensic autopsy (

18). Additionally, the accuracy of diagnoses in the Cause of Death Register is evaluated every second year in an independent study of random samples (

19). A systematic review of the reliability of suicide statistics found three studies from Sweden among the 31 meeting inclusion criteria, all three of which supported the accuracy of the Swedish data (

20). Third, in our definition of suicide, undetermined deaths were included to minimize the possible effect of spatial and secular trends in the assignment of cases of suicide death (

21). Fourth, we studied individuals born across three decades, which also required our definition of stepfathers to differ slightly across cohorts, and our findings could mask large cohort differences. We investigated this by analyzing separately the first and second chronological halves of our cohort. Differences were small between the older and younger cohort, as shown in Table S1 in the

online supplement.

Conclusions

Suicide attempt is strongly transmitted from parents to their children, and this transmission arises nearly equally from genetic and rearing effects. While parental psychiatric and substance use disorders can explain almost half of the genetic transmission of suicide attempt across generations, these disorders had no effect on the impact of being reared by a nonbiological parent with a history of suicide attempt. Suicide death is modestly transmitted across generations, with genetic effects likely being more important than rearing effects. While suicide attempt and suicide death are substantially genetically correlated, a model that proposes that they reflect quantitatively different degrees of severity on the same continuum of liability can be ruled out.