In this issue of the

Journal, Vidal-Ribas and colleagues (

1) highlight many of the challenges in identifying biological markers that confer risk for suicidal behaviors in preadolescent youths. Lifetime suicidal thoughts and behaviors were assessed in a large sample (N=7,994) of children ages 9–10 years recruited through the Adolescent Brain Cognition Development (ABCD) project. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors were most closely associated with child psychopathology, family conflict, and parental psychopathology. The strongest neural correlate was an association between suicidal thoughts and behaviors and decreased thickness of the superior temporal gyrus. Psychosocial and neuroimaging findings only modestly discriminated between those with and without lifetime suicidal thoughts and behaviors. This study is timely, as the rate of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among preadolescents is increasing rapidly (

2), most notably among females, as well as Black youths, for reasons that are poorly understood. Despite recent efforts, no definitive neural correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors have been identified (

3).

Although the superior temporal gyrus is not a usual suspect in neural markers related to suicide risk, this study, as the authors note, is not the first to identify an association between structural integrity of this region and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (

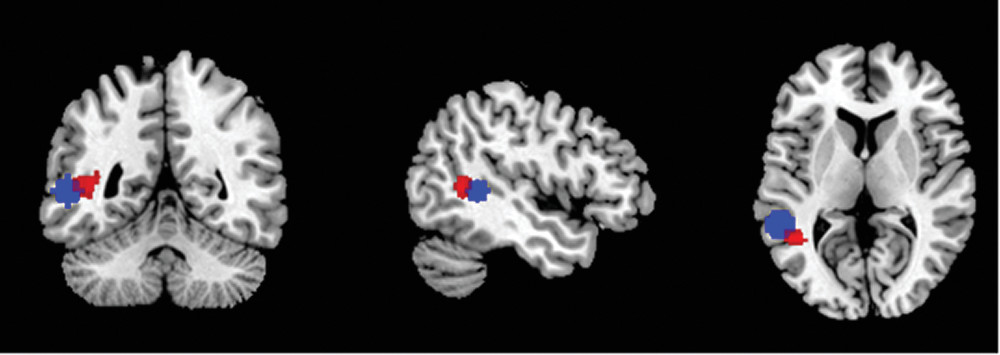

4). Alterations in resting-state functional connectivity have also been observed in a nearby region (

Figure 1) (

5). The authors’ stringent, unbiased approach greatly diminishes the likelihood that this finding is a false positive, while also ensuring that all regions of the brain received adequate attention. A conventional neurofunctional interpretation of the region does not lend itself to extant theories of suicide, as the region is mostly associated with language. There is, however, a growing body of functional and structural literature that also links the region’s function to social cognition (

6,

7). To provide a more comprehensive overview of the region’s functional role, we performed a decoding analysis using the BrainMap database implemented in Mango software (

http://ric.uthscsa.edu/mango) (

8). This approach can be useful for providing a broad overview of which cognitive domains might show a functional association with a region’s activity by identifying types of paradigms (e.g., language, sensorimotor, cognition, and emotion) that activate the region more often than would be expected by chance. This type of analysis is performed in volume rather than surface space, and thus the authors kindly provided the peak Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates (x=−54.34, y=−44.54, z=4.16) defining the regions of significant difference. We then created a spherical region of interest with a 10-mm radius centered on this peak and converted it into Talaraich space. As expected, language-related paradigms (speech/semantics: all z values >5.1) frequently activated the region. However, an intriguing finding was seen just below the standard threshold (z=3), namely for social cognition (z=2.93). With regard to suicide, an association between alterations in social behavior and suicide is in line with previous findings, as a common precipitant for preadolescent suicide is conflict with parents or peers (

9). At the very least, the present analyses provide justification for further targeted analyses of the left superior temporal gyrus in suicidal thoughts and behaviors, perhaps including seed-based functional connectivity analyses and paradigms designed to evaluate social behavior.

There are numerous strengths to this study. Vidal-Ribas and colleagues have been scrupulously careful to control for multiple comparisons and to indicate the clinical significance of statistically significant findings. This respectful and cautious approach to data analysis and interpretation should be a model for the field. In particular, their unbiased and comprehensive approach ensures that the significant finding they observed in the superior temporal gyrus is sufficiently strong (Cohen’s d=0.17) to warrant further attention. This state of affairs is not always the case in very highly powered studies, as rather modest findings can be statistically significant if the power is sufficiently high. Taking a step back from the current findings, however, the broader question is how we build on this and related work in suicide among youths. Herein, we offer tentative signposts to guide future work.

First, as the authors acknowledge, a key challenge in interpreting the present data is the temporal and phenomenological breadth of the primary phenotype, lifetime suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Prior research has shown that there may be core differences among youth suicide ideators and attempters (e.g., interpersonal stress exposure [

10], anhedonia and reward processing [

11], and familial transmission [

12]). Furthermore, there is evidence that functional connectivity and task-based neural activation are sensitive to whether suicidal thoughts and behaviors are current or more distal (

13). Accordingly, comparing current ideators with and without a history of recent suicide attempts may elucidate mechanisms that facilitate the transition from ideation to action. Relatedly, longitudinal studies that prioritize enrollment for ideators enriched with those at high risk of making a future suicide attempt—based on a prior attempt history, family history of attempts, or a risk calculator—may validate biological markers implicated in suicide attempts and deaths over time.

Second, suicide risk may be best understood through the identification of interactive, and potentially transactional, processes that shape the emergence of suicidal behaviors (

3). Biological diatheses may be a necessary but not sufficient predisposition to engage in suicidal behaviors. In the presence of specific environmental exposures, however, the likelihood of suicidal behaviors may increase. Previous work in adolescence has underscored the importance of peer-related interpersonal stressors often related to romantic attachments as it relates to suicidal behaviors (

10), whereas preadolescent suicide decedents often have conflict with family or peers (

9). Testing models that account for these developmentally salient environmental exposures and their interaction with biological vulnerability may clarify the pathway for suicidal behaviors among preadolescent youths.

Third, the ABCD project affords access to methodologically rigorous neuroimaging and clinical data. Critically, participants will be followed through preadolesence into early adulthood, a period characterized by a surge in depressive disorders and interpersonal stress exposure (

9,

14), which are known correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Repeated scans during a period of intense neuromaturation will provide an unprecedented opportunity to determine whether deviations in normative development are related to suicidal thoughts and behaviors, above and beyond contributions from underlying mental disorders. Enriching the overall ABCD design with ambulatory assessments may illuminate temporal patterns of risk factors leading up to suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Wearables (particularly for younger children) and smartphone apps collect real-time data that provide unique access to dynamic changes in sleep, emotional distress, and social interactions, risk factors repeatedly implicated in suicidal behaviors (

15). Coupled with ecological momentary assessment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, in-lab biological markers—including but not limited to structural and functional neural correlates, as well as event-related potentials—can be linked to real-time functioning in the service of clarifying longitudinal predictors of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. It is impractical to follow the entirety of the ABCD sample; however, focusing on an enriched subset of youths at high risk to make a transition from ideation to attempt (e.g., current suicidal ideation with plan and/or suicidal intent) could provide an important roadmap for clarifying central biological markers and associated socioemotional states that inform the timing of suicidal behaviors.

An open question in the field is to what extent neuroimaging—and what modality therein—will improve our understanding of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among youths. The relatively low discriminatory power of the suicidal thoughts and behaviors correlates may have prompted Vidal-Ribas and colleagues to be unduly pessimistic in the interpretation of their findings. Given their methodologically rigorous approach, the authors are well positioned for a longitudinal sequel, accounting for variations in neuromaturation and stress exposures during a critical period of neural and socioemotional development. Integrating these interactive and transactional processes may shed light onto the growing problem of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among preadolescent youths and perhaps motivate innovative treatments that reduce the needless loss of young lives.