People with mental disorders (schizophrenia spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder, and depressive disorders, among others) have poorer physical health than the general population (

1,

2), with a higher burden of risk factors for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), diabetes (

3), metabolic syndrome (

4), poor nutritional habits (

5,

6), more sedentary behavior (

7), and smoking (

1). Pharmacological treatment of mental disorders, including second-generation antipsychotics, also contribute to poor metabolic status (

8). According to a large-scale meta-analysis (

9), people with mental disorders have a high prevalence of CVD (9.9%), and among those with severe mental disorders, the incidence of CVD is roughly 80% higher than in the general population. Mental disorders appear to be independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease, and a variety of putative causal mechanisms may explain this (

10). This independent relationship has been best studied and established for depression (

11), although there is compelling evidence of independent associations, from prospective studies, of other mental disorders with cardiovascular disease and mortality, especially for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (

9,

12), and less so for the anxiety disorders (

10,

12).

Several medical conditions and CVDs contribute to a large extent to the reduction by 10–20 years in longevity among people with mental disorders (which is only partially due to suicide, which accounts for the largest relative mortality risk, but has lower prevalence than CVD) (

13–

17). Beyond increased incidence, the stage at which medical comorbidities are diagnosed and the quality and timeliness of care play a role in determining disease course and outcome. For instance, while the overall incidence of cancer in people with mental disorders is similar to that of the general population, mortality from cancer in both sexes is elevated in people with mental disorders (

18), with higher fatality rates for cervical, breast, and overall cancer compared with the general population (increased mortality risks of 100%, 23%, 50%, respectively) (

19,

20). Such increased cancer fatality among people with mental disorders might be explained by poor cancer screening, barriers to access to treatment, or lower-quality treatment. While access and treatment quality remain to be investigated, disparities in cancer screening have been demonstrated. A recent meta-analysis (

21) that included 4,717,839 individuals (501,559 of whom had mental disorders) showed that people with mental disorders are less likely to be screened for any, breast, cervical, or prostate cancer (odds ratios, 0.76, 0.65, 0.89, and 0.78, respectively), and women with schizophrenia in particular have lower screening rates.

A rigorous synthesis of the available evidence is paramount to determine whether disparities of this kind exist and to assess their type and extent. However, no recent comprehensive meta-analysis, without restriction in types of CVDs or types of mental disorders, has investigated disparities in CVD screening and treatment. To the best of our knowledge, the latest systematic reviews on disparities in medical prescriptions in people with mental illness compared with the general population was published by Mitchell et al., in 2012 (

23), with the last search conducted in 2010. Since then, a number of studies have been published, reporting alarming disparities in CVD screening and treatment between people with and without mental disorders (

27). Furthermore, assessing sources of bias in observational evidence is crucial (

28). Particularly, confounding by indication—that is, not accounting for the expected higher frequency of screening and treatment for CVD in groups with a higher base rate of CVD (i.e., people with mental illness)—can lead to underestimation of disparities in observational evidence (

29,

30). Conversely, given increased rates of undetected and untreated CVD in individuals with mental disorders, studies comparing CVD screening and treatment without restricting the selection criteria to people with underlying CVD might also underestimate screening and treatment disparities.

Based on the above, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies measuring disparities in CVD screening and treatment between people with and without mental disorders. Our hypothesis was that significant disparities exist, with both reduced screening and treatment of CVD, both across CVDs and mental disorder groups.

Results

Search Results and Study Characteristics

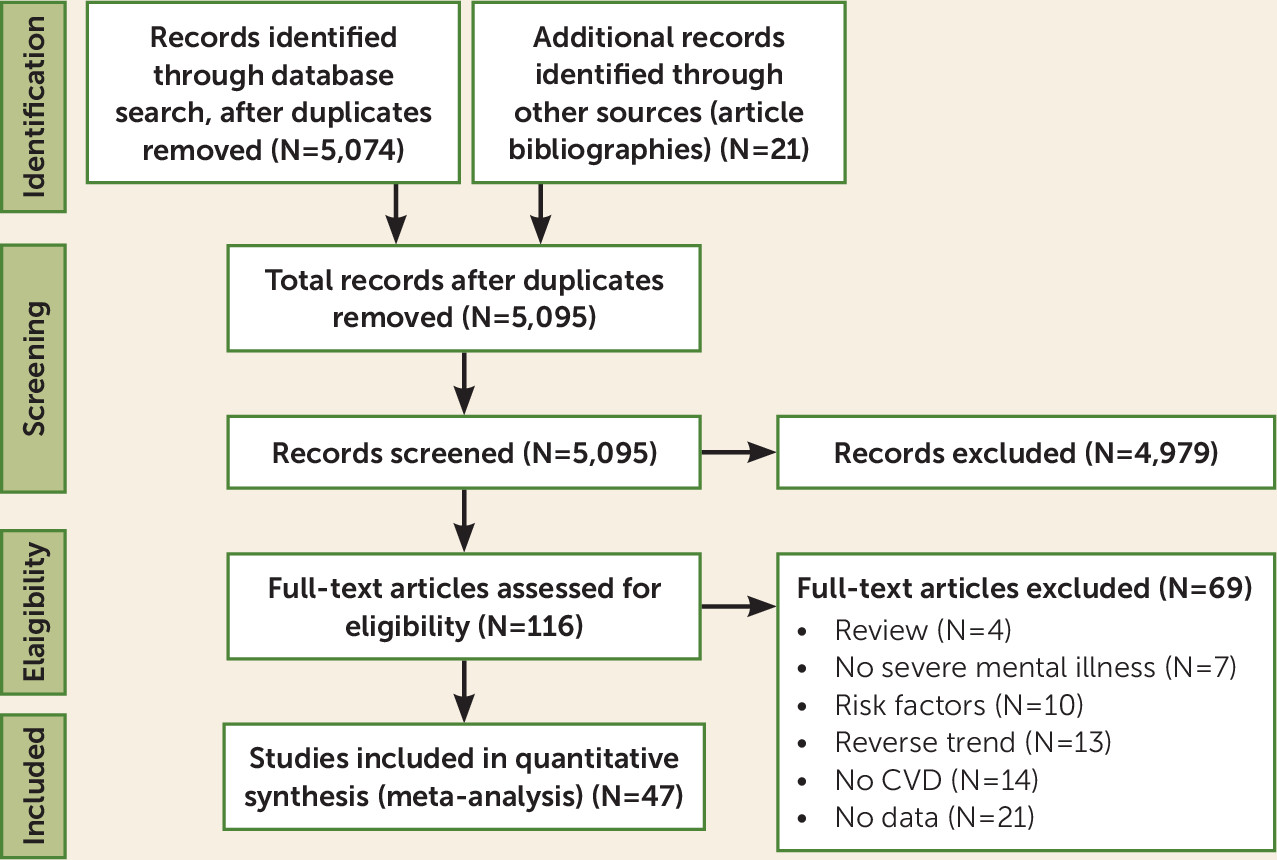

Search results and the study selection process are outlined in

Figure 1. Of 5,074 initial hits and 21 additional records identified through manual search, and after removing duplicates, we screened 5,095 studies at the title and abstract level, of which we selected 116 for full-text assessment. We excluded 69 studies after full-text assessment (see Table S3 in the

online supplement), and ultimately included 47 studies.

Detailed characteristics and references of included studies are reported in Table S4 in the online supplement. Overall, this meta-analysis reports data from 24,400,452 subjects, including 1,283,602 with mental disorders. The mean or median age was >65 years in 15 studies. Among people with mental disorders, 873,268 (68.0%) were diagnosed with mood disorders, 279,177 (21.8%) with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and 131,157 (10.2%) with other mental disorders (anxiety disorders, dementia, personality disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, and other, mixed disorders). Thirty studies (63.8%) included subjects with different disorders, 13 (27.7%) included subjects with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and four (8.5%) included subjects with mood disorders. Twenty-eight studies (59.6%) included subjects with CAD, including acute myocardial infarction, 15 (31.9%) with different CVDs, and four (8.5%) with cerebrovascular disease (CBVD), including stroke.

All populated continents except Africa and South America were represented. Twenty-one studies were conducted in the United States, seven in Denmark, five in Canada, three in the United Kingdom, two in Finland, two in Israel, two in Norway, and one each in France, Taiwan, Australia, Hong Kong, and the Netherlands. Overall, five studies were affected by confounding by indication. The quality of included studies was high (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale score ≥7) in 41 studies, with a median score of 8 (IQR=7–8) (see Table S5 in the online supplement).

Primary Outcome: Screening or Treatment for CVD

The main results for the primary outcome are reported in

Table 1. Patients with mental disorders had significantly lower rates of screening or treatment for any CVD (k=47, odds ratio=0.773, 95% CI=0.742, 0.805, p<0.001), for CAD (k=34, odds ratio=0.734, 95% CI=0.690, 0.781, p<0.001), for CBVD (k=8, odds ratio=0.810, 95% CI=0.779, 0.842, p<0.001), and for mixed CVDs (k=11, odds ratio=0.839, 95% CI=0.761, 0.924, p<0.001). Disparities were confirmed for patients with mood disorders for any CVD (k=19, odds ratio=0.842, 95% CI=0.786, 0.901, p<0.001), for CAD (k=13, odds ratio=0.827, 95% CI=0.750, 0.911, p<0.001), and for CBVD (k=4, odds ratio=0.811, 95% CI=0.768, 0.857, p<0.001), but not for mixed CVDs (p=0.397). Larger disparities emerged for patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders for any CVD (k=29, odds ratio=0.615, 95% CI=0.564, 0.671, p<0.001), for CAD (k=21, odds ratio=0.564, 95% CI=0.513, 0.620, p<0.001), for CBVD (k=5, odds ratio=0.717, 95% CI=0.626, 0.821, p<0.001), and for mixed CVDs (k=6, odds ratio=0.764, 95% CI=0.674, 0.866, p<0.001). Finally, for patients with mixed mental disorders, disparities were also confirmed for any CVD (k=25, odds ratio=0.836, 95% CI=0.787, 0.887, p<0.001), for CAD (k=18, odds ratio=0.819, 95% CI=0.760, 0.883, p<0.001), and for CBVD (k=4, odds ratio=0.849, 95% CI=0.808, 0.892, p<0.001), but not for any mixed CVDs (p=0.111).

Screening for Cardiovascular Disease

Meta-analyses on CVD screening disparities are reported in

Table 2. Regarding screening for any CVD, disparities emerged for any, mood, schizophrenia spectrum, and other mental disorders (odds ratios, 0.757, 0.877, 0.611, and 0.812, respectively; all p values <0.05). Similar results emerged for CAD in any, mood, schizophrenia spectrum, and other mental disorders (odds ratios, 0.718, 0.830, 0.552, and 0.856, respectively; all p values <0.05). For CBVD, a significant gap in CVD screening was confirmed in any mental disorder and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (odds ratios, 0.683 and 0.591, respectively; both p values <0.05), and only one study was included for mood and mixed mental disorders. For mixed CVDs, patients with any, schizophrenia spectrum, and mixed mental disorders had lower rates of CVD screening (odds ratios, 0.786, 0.775, and 0.730, respectively; all p values <0.05), while no difference emerged among those with mood disorders.

Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease

Meta-analytic results on CVD treatment disparities are summarized in

Table 3. Regarding treatment for CVD, across any, mood, schizophrenia spectrum, and mixed mental disorders, disparities emerged for any CVD (odds ratios, 0.765, 0.816, 0.597, and 0.843; all p values <0.05), for CAD (odds ratios, 0.728, 0.830, 0.556, and 0.816, respectively; all p values <0.05), and for CBVD (odds ratios, 0.811, 0.813, 0.719, and 0.849; all p values <0.05). For mixed CVDs, treatment was significantly less likely to be administered only for the any mental disorder category (odds ratio=0.837, p<0.05) and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (odds ratio=0.683, p<0.05), and not for mood disorders or other mental disorders.

Specific Procedures and Medications for CVDs

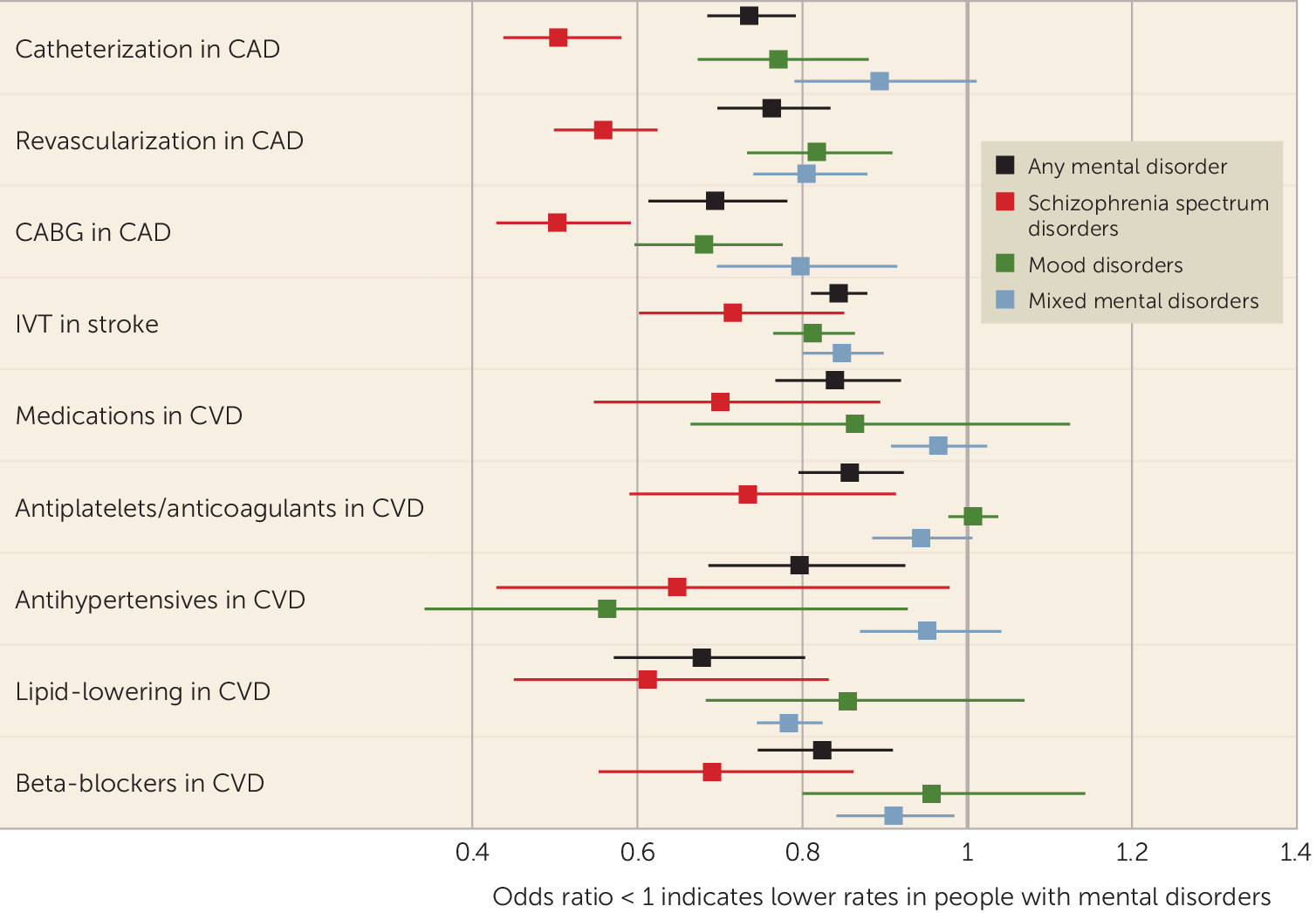

Disparities in specific procedures for CVDs across mental disorders are reported in

Figure 2. For catheterization in CAD, disparities emerged for any, mood, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (odds ratios, 0.736, 0.771, and 0.505, respectively; all p values <0.05), but not for mixed mental disorders. Similarly, in CAD, lower rates of revascularization emerged across any, mood, schizophrenia spectrum, and mixed mental disorders (odds ratios, 0.763, 0.818, 0.559, and 0.806; all p values <0.05), as well as lower rates of coronary artery bypass grafting (odds ratios, 0.694, 0.682, 0.504, and 0.798, respectively; all p values <0.05). A significantly lower frequency of intravenous thrombolysis in stroke emerged for any, mood, schizophrenia spectrum, and mixed mental disorders (odds ratios, 0.845, 0.813, 0.716, and 0.849, respectively; all p values <0.05). A gap in treatment with CVD-targeting medications emerged for any and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (odds ratios, 0.840 and 0.701, respectively; both p values <0.05), but not for mood or mixed mental disorders.

Notably, there was a significant gap for antiplatelet or anticoagulant treatment in any and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (odds ratios, 0.858 and 0.735, respectively; all p values <0.05), but not in mood and mixed mental disorders. Antihypertensives were less frequently used in patients with any and mood disorders (odds ratios, 0.797 and 0.649, respectively; all p values <0.05), but not in those with schizophrenia spectrum and mixed mental disorders. In any, schizophrenia spectrum, and mixed mental disorders, there was also less prescribing of lipid-lowering agents (odds ratios, 0.679, 0.613, and 0.784, respectively; all p values <0.05) and beta-blockers (odds ratios, 0.824, 0.691, and 0.911, respectively; all p values <0.05), but this was not the case in mood disorders.

Subgroup Analyses

Subgroup analyses (see Tables S6 and S7 in the online supplement) showed significant differences across countries regarding disparities in screening or treatment for any CVD (largest in Taiwan [odds ratio=0.384, 95% CI=0.289, 0.510], nonsignificant in France [odds ratio=1.163, 95% CI=0.979, 1.381]; subgroup comparison, p<0.001), for CAD (largest in Taiwan [odds ratio=0.384, 95% CI=0.289, 0.510], smallest in Finland [odds ratio=0.893, 95% CI=0.868, 0.919]; subgroup comparison, p<0.001), and for mixed CVDs (largest in the United Kingdom [odds ratio=0.289, 95% CI=0.150, 0.559], absent in France [odds ratio=1.163, 95% CI=0.979, 1.381]; subgroup comparison, p<0.001), but not for CBVD (p=0.505).

Meta-analytic estimates from studies vulnerable to confounding by indication failed to identify disparities in screening or treatment for any CVD, CAD, CBVD, and mixed CVD disorders. Subgroup differences emerged in screening or treatment for any CVD (p<0.05) and for CAD (p<0.05).

Meta-Regression

Higher study quality (beta=−0.018, standard error=0.009, p=0.046) and percentage female (beta=−0.003, standard error=0.001, p=0.004) moderated larger disparities. Age and sample size were not significant moderators (p values, 0.232 and 0.950, respectively).

Publication Bias

In main analyses on the primary outcome, publication bias was present in one association, and among sensitivity analyses in six associations. All associations remained significant after trim-and-fill analysis. The median fail-safe number was 364 in the main analysis (interquartile range, 163–3,666) and 476 in the sensitivity analysis (interquartile range, 171–2,652).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis investigated any CVD and specific CVD screening and treatment procedure disparities in more than 1.25 million people with mental disorders compared with more than 23 million people without mental disorders from four continents. The results indicate that people with mental disorders suffer from significantly lower screening for or treatment of any CVD, CAD, CBVD, and other CVD, including heart failure, and that these disadvantages extend across different mental disorders, being highest in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

These findings extend previous narrative reviews and confirm the hypothesis that people with mental disorders undergo fewer screening and treatment procedures for CVDs than the general population, although people with mental illness have a greater likelihood of having and dying from CVDs (

1,

9). The results are consistent with previous work from Mitchell and colleagues, who showed that people treated with antipsychotics (as a proxy indicator of having mental disorders) receive less metabolic screening than mandated by guidelines (

39) and that people with mental disorders receive lower metabolic quality of care for CVD in general (

40), less frequent revascularization in coronary artery disease (

25), and fewer prescriptions of medications for physical disorders (

23). However, our data expand these previous findings by including any mental disorder, any screening and treatment procedures, and for any CVD, in one quantitative evidence synthesis and by having a more than tenfold larger sample size. The results show that disparities in physical health care of people with mental disorders clearly and concerningly extend beyond cancer screening (

21), diabetes care (

41,

42), and treatment of metabolic syndrome (

43–

45).

There are many possible reasons for these disparities in the management of CVD in people with mental disorders. First, mental health professionals reportedly undertake physical examinations in less than 50% of people with mental disorders (

46). Second, mental health professionals often do not feel confident in prescribing physical health medications and leave the task to physicians in primary care, internal medicine, or specific medical specialties (

23). Third, family physicians spend less time with persons with mental disorders than with other patients (

40,

47), possibly because they have to deal with frequently overly busy schedules and the competing demands of other patients (

48,

49). Similarly, low mental health literacy among non–mental health professionals may result in stigma and barriers to offering treatment (

50). Indeed, overshadowing of mental disorders, limiting health care for physical disorders, frequently occurs. Fourth, symptoms and impairment in social functioning and in cognition, reduced illness insight, nonadherence to treatments, and financial or insurance problems may compromise health care access and utilization, especially when people with mental illness live in poverty or have no fixed address (

21). In this context, social withdrawal, avoidance behavior, and depressed mood, among other symptoms, could contribute to the patient’s reduced interest in self-care, including medical care (

21). Core symptomatology could be a determining factor in schizophrenia, as patients with schizophrenia reportedly have fewer medical visits and fewer documented medical problems compared with people with depression (

51). This factor could explain the fact that disparities in CVD screening and treatment are largest in schizophrenia. Patients with schizophrenia frequently also do not accept proposed treatments, after acute myocardial infarction, for instance (

52). Fifth, physicians may disregard physical complaints by patients with mental illness, as a result of diagnostic overshadowing (the assumption that the complaint results from the mental condition) (

53,

54). Sixth, physical and mental health care providers often deliver care in “silos,” limiting comprehensive care for both physical and mental illness (

55). Seventh, people with mental disorders tend to receive CVD care too late, when the disease is already well established, rather than receiving preventive care when risk factors, such as diabetes and hypertension, first appear. This problem has been shown in comparison with the general population according to data collected from Medicaid and Medicare in the United States (

55). Indeed, people with mental illness are less likely to receive blood glucose and lipid tests, hospital care, and medications for diabetes (

56).

Importantly, the present results suggest that disparities in CVD status between people with and without mental disorders are actually larger than previously reported (

9). If those with mental disorders are infrequently screened for CVD, many may die without their CVD ever being diagnosed or treated. Such a hypothesis is supported by evidence from a study reporting on 72,451 people who died from CVD, showing that individuals with schizophrenia and women with bipolar disorder were, respectively, 66% and 38% less likely to be diagnosed with CVD before their CVD-related death (

57). Conversely, timely pharmacological treatment of CVDs could substantially reduce the high premature mortality rates typically observed for people with mental disorders (

58).

Specific interventions should be tested in randomized clinical trials. A possible approach to avoid delaying CVD diagnosis and treatment could be to routinely offer a CVD risk assessment to patients accessing mental health services and to establish a close, efficient collaboration with cardiology services, where patients with elevated CVD risk can be referred (

59). Mental health professionals could then follow up with patients regarding cardiologists’ prescriptions, to promote treatment adherence. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of this pathway could be tested in cluster-randomized clinical trials, with centers randomly assigned to either CVD screening plus dedicated cardiologist referral (experimental arm) or treatment as usual (control arm). The experimental arm should be tailored to specific health care organizations across different countries, as well as to the magnitude of disparities in each country. Any rehabilitative treatment should aim to promote autonomy and recovery, ultimately leading patients with mental disorders to autonomously use health services, as the general population does. The real-world evidence included in the present work shows that this autonomy remains to be achieved and that specific adjustments to facilitate CVD screening and treatment are needed to counter both lack of prescription of and adherence to CVD screening and care in people with mental disorders.

Importantly, the need to improve screening and treatment for physical conditions in people with mental disorders extends to acute-setting health care service utilization (hospitalization, emergency department) for physical health (

60), suggesting that disparities in screening and treatment of physical disorders might go beyond CVD, despite effective options being available (

61). Finally, our findings are also important from a methodological standpoint. The results clearly show that studies biased by confounding by indication either underestimate the gap in CVD screening and treatment as a result of undetected CVDs in people with mental illness or overestimate screening and treatment as a result of higher frequencies of CVDs in people with mental illness compared with the general population, failing to find existing disparities in CVD screening and treatment for people with mental disorders. Additionally, studies with relatively lower quality reported relatively smaller disparities.

This work has several strengths. It is the largest and most comprehensive evidence synthesis on CVD screening and treatment disparities in people with mental disorders to date. It includes high-quality observational studies. It sheds light on mechanisms underlying poor CVD status, with considerable clinical and service organization implications. And it supports the research and evidence-synthesis recommendations from the

Lancet Psychiatry Commission’s “blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness” (

1).

The study is also not without limitations. First, virtually all analyses showed high heterogeneity. However, we identified moderators, which could be responsible for heterogeneous estimates, such as country, confounding by indication, and study quality. Second, observational studies are affected by several types of bias, which even high-quality meta-analytic methodology can only partially address (

28). Finally, scant evidence was available from low- and middle-income countries.