Exposure to adversity is a common childhood experience. In an early study examining adverse childhood experiences, 52.1% of adult respondents retrospectively reported exposure to at least one adversity (

1). Such childhood exposures have been associated with wide-ranging health risks in adulthood, including ischemic heart disease, alcohol use disorder, and depression (

2). Subsequent studies have used longitudinal designs and followed participants prospectively from childhood into adulthood with repeated assessments. These prospective studies have documented higher levels of exposure to childhood adversity than has been reported in the retrospective studies (

3,

4). These different strands of research document that childhood adversity exposure is common and that children exposed to such adversity have poor outcomes in adulthood.

Mental health problems are common as well. Only 12%–15% of youths have a mental illness at any given time (

5), but more than 40% of children have met criteria for a common psychiatric disorder by age 16 (

6,

7). This estimate fails to include children with subthreshold problems, which cause significant impairment in important aspects of life (

8,

9) and are associated with an increased risk of having psychiatric problems and serious impairment in adulthood (

6,

10). When children with subthreshold symptoms are included, it is clear that more children than not have experienced psychiatric problems at some point in childhood (

6).

If both childhood adversity and mental health problems are common childhood experiences, then what does this mean for our notions of resilience? Resilience is commonly defined as better-than-expected adaptation in the presence of risk (

11,

12). Children who are unaffected by mental health problems despite exposure to childhood adversity are commonly considered resilient. Studies that assess childhood adversity and mental health problems suggest that such resilience may be uncommon. Most studies of childhood resilience, however, focus on only one specific type of childhood adversity (e.g., maltreatment or peer victimization) and then link that exposure to one mental health outcome (e.g., depression or anxiety). Yet in reality, many children experience multiple forms of childhood adversity (

13–

17). Indeed, a cumulative measure of exposure to multiple adversities is among the best predictors of childhood psychopathology (

18–

20). Finally, studies of resilience are typically conducted within childhood or adolescence. Few studies have followed resilient children over the long term to observe how they fare as adults.

This study takes a comprehensive, long-term perspective on resilience from childhood into adulthood. We used up to eight childhood assessments of a broad range of adversities and summarized these experiences into an index of cumulative childhood adversity exposure. We also assessed mental health during childhood and adulthood. During childhood, we defined children as resilient if they were exposed to multiple adversities but remained free of any mental health problems (including subthreshold problems), as is common convention. We then investigated whether the children classified as resilient in childhood remained free of mental health problems during their early adult years (ages 25 and 30), and whether these individuals functioned well in important life domains. Our two main objectives were to determine how common childhood resilience is and to characterize how children who were defined as resilient during childhood fared in their early adult years.

Methods

Participants

This report follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines for cohort studies (

21). The Great Smoky Mountains Study is a longitudinal, representative study of children in 11 predominantly rural counties of the southeastern United States (see

22) that began in 1993. Three cohorts of children, ages 9, 11, and 13 years, were recruited from a pool of approximately 12,000 children, using a two-stage sampling design that resulted in 1,420 participants (49% female) (see also

23). Potential participants were randomly selected from the population in a household equal probability design; participants who screened high for risk of psychopathology were oversampled. American Indians were oversampled to constitute 25% of the sample. Sampling weights were applied to adjust for differential probability of selection and to allow results to generalize to the broader population. The participant selection process is summarized in Figure S1 in the

online supplement (see

22–

24 for additional details).

Annual assessments were conducted with the participants and their primary caregivers until participants turned 16 years old; thereafter, participants were interviewed alone at ages 19, 21, 25, and 30 (data from ages 25 and 30 are used here). An average of 83% of all possible interviews (N=11,233) were completed; by age 30, 39 participants had died. Before the interviews, all participants and their parents (up to age 18) signed informed consent forms approved by the Duke University Medical Center ethical review boards. Participants received compensation for their time ($100 in the most recent waves).

Childhood Mental Health Status

Psychiatric disorders were assessed with the structured Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) until age 16 (

25). A 3-month primary period was used to assess psychiatric symptoms. A symptom was counted as present if reported by the parent, the child, or both. Scoring programs implemented in SAS (version 9.4) combined information about the date of onset, duration, and intensity of each symptom to establish DSM-IV diagnoses. A 2-week test-retest reliability study of CAPA diagnoses in children ages 10–18 found kappa values ranging from 0.5 for conduct disorder to 1.0 for substance dependence (

26). Common childhood psychiatric disorders assessed included anxiety disorders, mood disorders, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and substance use disorders. Subthreshold problems were defined as impairments resulting from psychiatric symptoms that did not meet full diagnostic criteria. Childhood impairment was assessed in 17 domains of functioning (e.g., self-care, academic performance, and peer relations), using definitions and rules specified in the CAPA glossary and the interview schedule (

8,

27). The test-retest intraclass correlation coefficient for level of psychosocial impairment by child self-report was 0.77 (

27).

Childhood Adversities

A broad range of childhood adversities were assessed with the CAPA at assessments conducted between ages 9 and 16. Experiences of childhood adversity were categorized into five types: low socioeconomic status, unstable family structure, family dysfunction, maltreatment, and peer victimization. Table S1 in the

online supplement provides comprehensive details about each indicator, how they were defined, and their frequencies in the sample. A codebook for all individual risk items is available at

http://devepi.duhs.duke.edu/codebooks.html.

Assessments in Adulthood

Psychiatric disorders, substance use disorders, and functioning in important life domains were assessed at ages 25 and 30. All adulthood measures were aggregated across these two assessment points. Except where noted (e.g., official criminal records), the measures were assessed with the Young Adult Psychiatric Assessment (

28), an upward extension of the CAPA interview. The assessment of adult psychiatric disorders resembled that of childhood disorders but relied on self-report only. The assessed disorders included anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder, and illicit drug use disorders as defined in DSM. In addition, standardized scales were derived to provide a broad profile of functioning across four domains: health, risky or illegal behaviors, wealth (financial or educational functioning), and social functioning. The scale scores were summed from dichotomous indicators in each domain (e.g., college completion for wealth and smoking status for health). In some cases, indicators were coded positive if reported at any point in adulthood; in other cases (e.g., educational attainment), the last observation was used to determine status. Standardized scores were obtained by subtracting individuals’ scores from the group mean score and dividing the result by the standard deviation. Table S2 in the

online supplement provides additional details about the scales and each of the indicators.

Analytic Strategy

Sampling weights were applied in all analyses to ensure that the results represented unbiased estimates of the measures in the original sample population. This approach was implemented by using the WEIGHT option in SAS PROC GENMOD. Consistent with common conventions, all percentages provided in the Results section are weighted percentages, and the N and sample size values are unweighted. All weighted regression models used Wald tests implemented in PROC GENMOD, with robust variance (sandwich type) estimates derived from generalized estimating equations to adjust the standard errors for the stratified design. All models were adjusted for sex at birth.

Primary analyses involved comparisons of groups defined by their experience of childhood adversity and psychiatric problems. The three groups included participants exposed to multiple adversities in childhood who never displayed psychiatric problems (the resilient group), participants exposed to one or fewer adversities in childhood who never displayed psychiatric problems (the low-risk/no-disorder group), and participants who displayed psychiatric problems in childhood (the childhood-disorder group). Between-group comparisons focused on diagnostic and functional outcomes as adults. In the case of diagnostic status as an adult (e.g., dichotomous outcomes), Poisson regression was used, as recommended for common outcomes (

29). In the case of the functional scales, the distribution was either Poisson or negative binomial, if there was evidence of overdispersion. Means ratios are reported for Poisson and negative binomial models. All tests were two-tailed and assumed a significance threshold of 0.05. Because no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, p values should be considered nominal.

Missing Data

Of the living 1,381 participants, 1,266 participants (91.7%) were followed up at ages 25 or 30. Table S3 in the online supplement includes comparisons of sex, each adversity variable, and childhood psychiatric problems between the original sample (N=1,420) and the sample followed into adulthood (N=1,266). There was no evidence of differences between these groups. The follow-up sample (N=1,266) was also compared to the sample of participants who were not followed up (N=154). Although there were no significant differences, the group that was not followed up included more male participants (57.6% vs. 50.3%, p=0.09) and individuals from families with low socioeconomic status (40.8% vs. 33.2%, p=0.09).

Results

Of the 1,266 participants followed into adulthood, only 25.6% (N=325) had not met criteria for either a full psychiatric diagnosis or a subthreshold disorder (i.e., some symptoms but no psychiatric diagnosis) by age 16. Participants without childhood psychiatric problems had lower levels of all types of childhood adversities (

Table 1). Nevertheless, many individuals in this group had experienced at least one form of adversity during childhood.

Cumulative childhood exposure to adversity was estimated by counting the number of categories of adversity experienced (of the five that were assessed).

Figure 1 shows the relative proportions of participants with and without psychiatric problems, stratified by the number of exposures to childhood adversity. With each additional domain of childhood adversity experienced (i.e., treating number of adversities as a continuous variable), the risk for having a childhood disorder increased significantly (risk ratio=1.7, 95% CI=1.5–1.9, p<0.001). Risk was highest among individuals who experienced multiple forms of childhood adversity: only 12.2% (N=63 of 650) of individuals experiencing adversity in two or more domains were free of childhood psychiatric problems, compared with 52.4% (N=262 of 616) of participants experiencing adversity in one or fewer domains (p<0.001). Thus, most children without a psychiatric problem had exposure to fewer types of childhood adversity. The approximately 12% of children who did not have mental health problems despite a level of childhood adversity that is commonly associated with psychiatric problems would be considered resilient based on much of the literature (i.e., a high level of risk coupled with no psychiatric problems). Children in this resilient group did not significantly differ by sex (53.1% male, 46.9% female; p=0.74). Subsequent analyses compared this resilient group with two other groups: children without psychiatric problems and a low level of adversity exposure (low risk/no disorder) and children with psychiatric problems (childhood disorder). A comparison of these three groups in terms of childhood adversities is provided in Table S3 in the

online supplement.

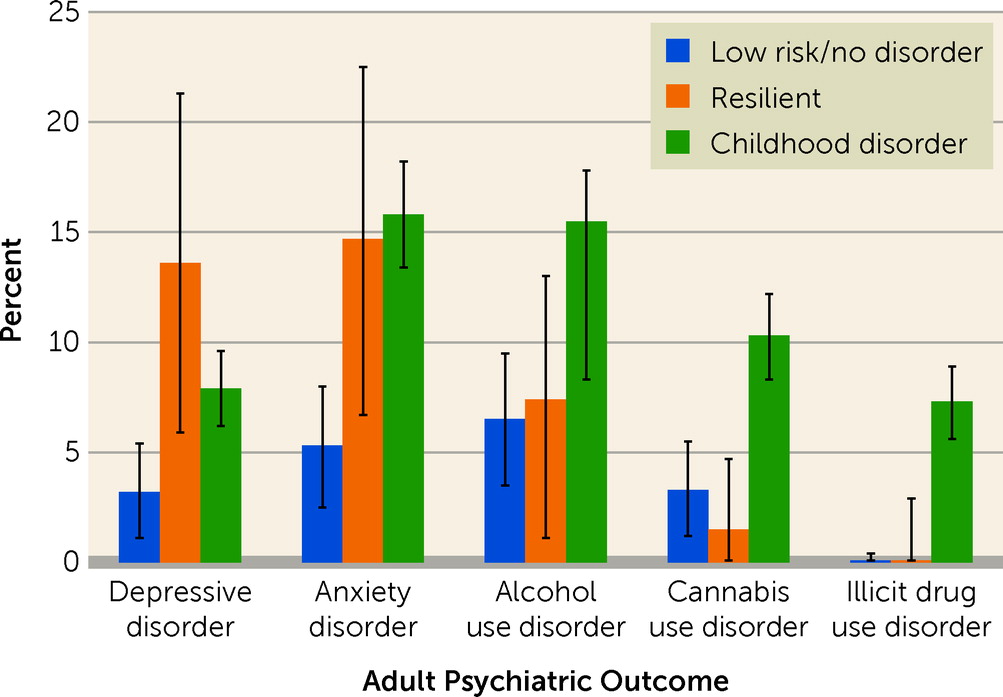

The next question was how these groups, defined by their childhood adversity coupled with their childhood psychiatric history, fared in adulthood. First, we looked at adult psychiatric status at ages 25 and 30 (

Table 2 and

Figure 2). Compared with the low-risk/no-disorder group, the resilient group was at greater risk of having an anxiety disorder (risk ratio=2.9, 95% CI=1.0–9.1, p=0.04) or a depressive disorder (risk ratio=4.5, 95% CI=1.1–16.7, p=0.03) in adulthood. There were no differences in risk of diagnosis of adult psychiatric disorders between resilient individuals and those with a childhood disorder. Findings differed for substance use disorders. The resilient group was not at increased risk for adult substance use disorders compared with the low-risk/no-disorder group (p values ranged from 0.96 to 0.34). The resilient group generally had lower levels of substance use diagnoses than the childhood-disorder group, although these differences did not meet conventional statistical thresholds. Thus, compared with the low-risk/no disorder group, the resilient group was at increased risk for adult emotional disorders but not substance use disorders.

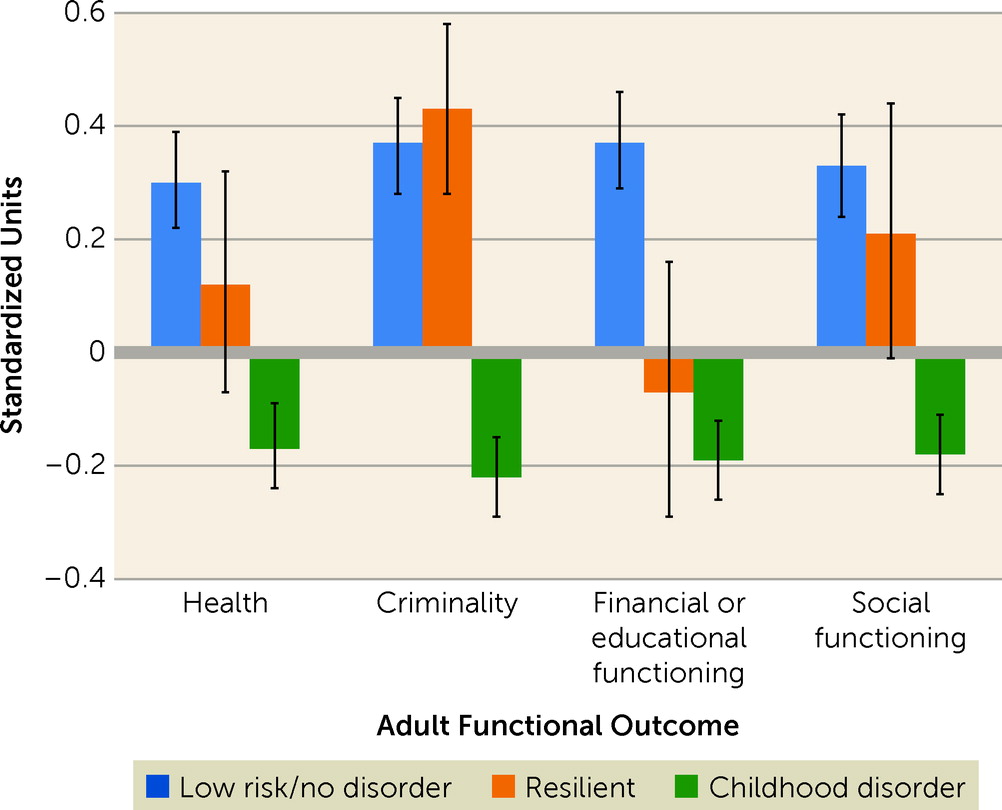

We also compared the groups in terms of four domains of adult functioning: physical health, criminality, financial or educational, and social functioning (

Table 2). Scale scores were standardized to facilitate comparisons, with higher scores indicative of better function (

Figure 3). The low-risk/no-disorder group had the highest level of adult functioning, with the exception of criminal behavior. Compared with the low-risk/no-disorder group, the resilient group had worse physical health (means ratio=0.7, 95% CI=0.5–0.9, p=0.008) and financial or educational functioning (means ratio=0.6, 95% CI=0.5–0.7, p<0.001); however, the groups were similar in the domains of criminality and social functioning. The resilient group had better functioning compared with the group of participants with childhood psychiatric problems in the domains of health (means ratio=1.4, 95% CI=1.2–1.8, p=0.001), criminality (means ratio=2.5, 95% CI=1.8–3.5, p<0.001), and social functioning (means ratio=1.5, 95% CI=1.2–1.9, p<0.001), but not financial or educational functioning. Thus, the well-being of adults who had been characterized as resilient children was better than that of the adults with childhood psychiatric problems but sometimes worse than that of adults exposed to less childhood adversity.

To test whether the results were robust to alternative group definitions, models were retested with a resilient group that was defined based solely on exposure to maltreatment, rather than a broader range of adversity variables (e.g., low socioeconomic status and family dysfunction). Thus, individuals in the resilient group had experienced childhood maltreatment (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect), but they had not met criteria for either a full psychiatric diagnosis or a subthreshold disorder. Results from this reanalysis are provided in Table S4 in the online supplement. All statistically significant associations in primary analyses were also observed in this sensitivity analysis.

Finally, one possible explanation for the observed pattern of results is that children in the resilient group continued to experience adversity at a high level in adulthood. To test this possibility, we compared adult exposure to traumatic events across the three groups. Exposure to trauma in adulthood was reported by 23.3% of participants in the resilient group (N=9 of 63), compared with 2.9% of those in the low-risk/no-disorder group (N=14 of 262) and 8.3% in the childhood-disorder group (N=81 of 941). The level of adult trauma exposure in the resilient group was higher than that in both the low-risk/no-disorder group and the childhood-disorder group (p values, 0.002 and 0.03, respectively). Inclusion of adult trauma in the primary analyses partially attenuated the association between childhood resilience and adult anxiety and depressive disorders.

Discussion

Although psychiatric problems are a common experience in childhood (

6,

7,

10), about one in four children in the Great Smoky Mountains Study failed to experience any such problems, even at a subthreshold level. The vast majority of children without psychiatric problems had limited exposure to the types of early childhood adversity that typically evoke such problems. Only about one in eight of the children exposed to multiple forms of adversity did not display subthreshold or fully diagnostic psychiatric problems in childhood, thus meeting common definitions of resilience. In other words, when comprehensively measuring exposure to adversity and psychological problems over longer periods of time within childhood, resilience to childhood adversity is uncommon.

But how does this small group fare in terms of their well-being in the long run? Children characterized as resilient had a greater risk of depression and anxiety in adulthood, but not substance use disorders, compared with children exposed to fewer forms of adversity and remained free of childhood psychiatric disorders. In terms of their everyday functioning, children characterized as resilient were doing much better than participants with childhood psychiatric problems, but these resilient children were doing more poorly in the domains of physical health and financial or educational functioning than participants who had been exposed to fewer types of adversity and did not experience childhood psychiatric problems. Thus, exposure to childhood adversity appears to have a significant long-term effect that is delayed among individuals who initially appeared to be resilient.

Persistent mental health was strongly associated with minimal exposure to adversity. These individuals are fortunate. The importance of being fortunate when it comes to experiencing few adversities has been reported frequently (

18,

20,

30). In this study, nine out of 10 children who never displayed psychiatric problems were exposed to adversity in only one domain or were free of exposure to childhood adversity. Indeed, childhood resilience was rare among individuals exposed to multiple forms of childhood adversity. There are a number of reasons for this finding. First, our analysis included children with subthreshold psychiatric problems, who are sometimes categorized as resilient in other studies. Second, to avoid misclassification, our analyses included only participants who had multiple assessments during childhood. Third, we used a cumulative measure across domains and time to define adversity status. In other words, adversity status in our study was based on many aspects of the childhood environment, including home and school settings, across several years (

17,

31). Failure to measure these adversities or focusing on a single form of adversity might lead to the misclassification of the child’s overall history of adversity and thus overestimate the number of children who do not develop psychological problems in the face of adversity.

Good mental health in the face of significant adversity (i.e., resilience), however, did not always persist into adulthood. This finding was anticipated by a previous study that discussed the potential for early adversity to have either “sensitizing” or “steeling” effects on individuals in response to challenges in their future (

32). Some authors have argued that resilience to childhood adversity could be advantageous: successfully overcoming significant adversity early in life could prepare individuals for facing adversity after reaching maturity. Conversely, lack of exposure to all forms of adversity could deprive children of opportunities to cultivate the coping skills necessary to navigate the vicissitudes of life. However, neither of these reasonable hypotheses was fully supported by our findings.

Exposure to multiple forms of adversity had long-lasting effects in some domains, even if the effect was not immediately apparent (i.e., sleeper effect [

33]), and these effects were not pervasive across all areas of life. Resilient individuals generally did better than individuals who had childhood psychiatric problems, particularly when it came to adult substance use disorders. This finding is particularly notable given the strong association between childhood adversity and subsequent substance use problems. This study suggests that some of the risk associated with childhood adversity may be mediated by childhood mental health problems. Potential “costs” of resilience have also been reported in a follow-up to the Kauai Longitudinal Study, with some of the children who were characterized as resilient experiencing stress-related health problems as adults (

12). More recently, physiological costs of psychosocial resilience have been identified by Brody and colleagues in their sample of at-risk children from the southern United States (

34). Although resilient individuals may escape their childhood relatively unscathed, the stress of maintaining psychological health despite adversity may catch up with them later in development. Additionally, adversity continues to occur throughout the lifespan. In our study, resilient children who had experienced multiple forms of adversity in childhood were at the greatest risk for exposure to trauma in adulthood.

This study included a sample of participants that was representative of the southeastern United States but not representative of the U.S. population. Compared with the U.S. population, African American and Latino people were underrepresented, and the American Indian population was overrepresented. However, the rates of childhood psychiatric disorders in this study are similar to those in other representative samples that included higher levels of Hispanic and African American youths (

7). Although our measure of early adversity included risk factors with strong evidence of association with multiple common childhood psychiatric disorders, the degree of adversity is often subjective, and other experiences with the potential to influence emotional and behavioral functioning may have been omitted. Whereas our cumulative childhood adversity scale provides a broad picture of environmental risk, a similar measure of genetic risk was not tested because of the lack of replicated variants of risk for common childhood diagnostic disorders (e.g.,

35). Finally, the group of interest (i.e., resilient individuals) was small, and these analyses need to be tested in other studies that have carefully assessed psychosocial functioning longitudinally from childhood to adulthood.

Conclusions

In this sample, resilience was uncommon, and for many, it did not last. Exposure to adversity had an influence, even if the effects were delayed. In the unlikely scenario that it were possible to identify all the factors that promote resilience, identify all the children at significant risk, and teach these children to implement resilience factors effectively, the public health effect would likely be modest at best, and the children might nevertheless develop subsequent problems. Alternatively, reducing childhood exposure to adversity could strongly promote long-term health and exert a more substantial and long-lasting impact on public health. For example, reducing childhood poverty—which is often viewed as a “risk of risk,” because it co-occurs with and spawns so many other forms of adversity—could be a promising approach, which might be implemented through, for example, the expansion of the child tax credit or a universal basic income (

36). This is not to suggest that resilience-based interventions do not have a role within comprehensive efforts to reduce the burden of mental illness. But such efforts should come only in the context of widespread public health efforts to minimize exposure to childhood adversity. Finally, an unintended consequence of the notion of resilience for individuals who eventually develop psychological problems is stigma. On this point, our findings are quite clear: the development of some level of mental health problems is the normative response to significant adversity. Individual resilience followed by persistent mental health is rare and may not be a reasonable goal. Public health efforts should prioritize reducing risk and treating individuals who are ill.