The benefits of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in the treamtent of pediatric anxiety disorders have been well documented in numerous randomized control trials (

1), but the effects are moderate at best (

2). Given the high rate of anxiety disorders, which typically emerge in childhood and adolescence, and the fact that a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder during adolescence is associated with an increased risk for depression and suicide (

3), there is a critical need to improve the efficacy of treatments for pediatric anxiety disorders. One strategy to optimize psychological treatments is to identify the active mechanisms involved and for whom such interventions may be most effective. The study by Haller et al. in this issue (

4) is a step in that direction.

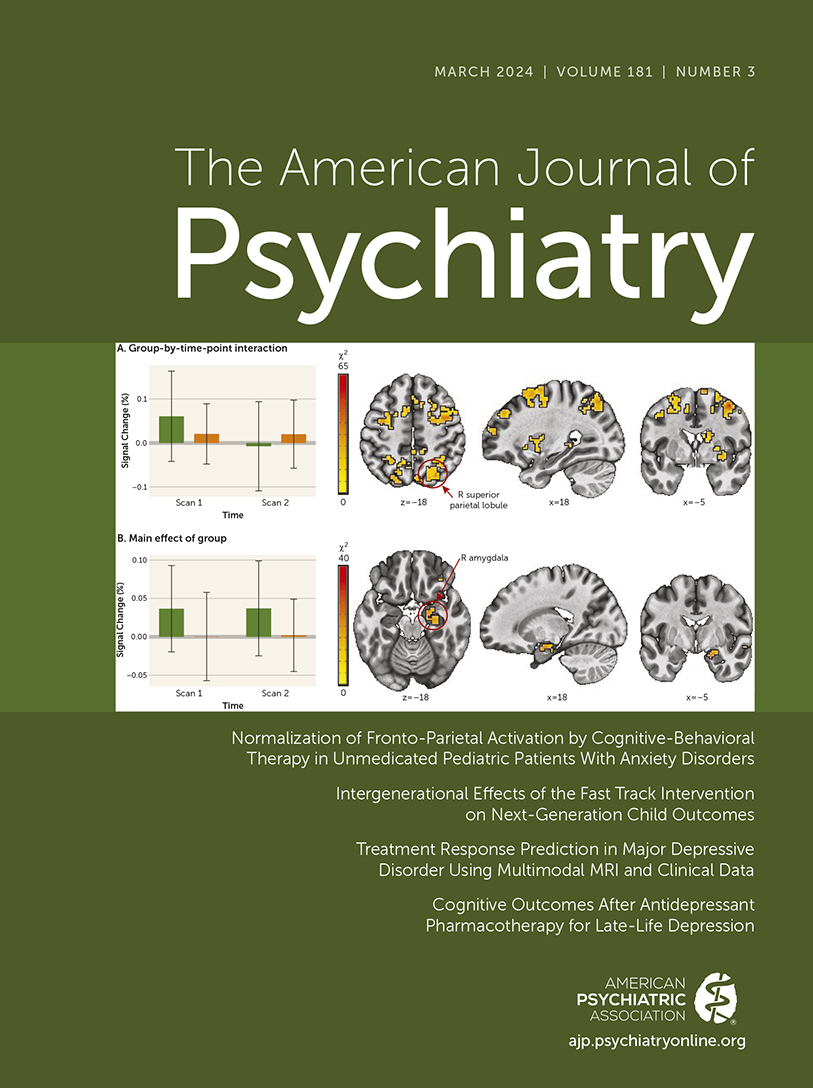

Haller et al. report that in a sample of unmedicated early adolescents diagnosed with a primary anxiety disorder (generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and/or separation anxiety disorder), neural activation in fronto-parietal networks (assessed during a dot-probe functional MRI [fMRI] task) normalized after 12 weeks of CBT, reaching levels in the range observed in the healthy comparison group. Interestingly, activation in several cortical and subcortical regions (e.g., motor cortex, amygdala/parahippocampal gyrus, and lateral anterior frontal regions) remained elevated in anxious youths after CBT, with some regions (e.g., temporal gyri, parietal lobule, occipital gyrus) increasing in activation, which was interpreted as indexing some form of compensatory processes. Surprisingly, although 66% of anxious youths were considered responders, there were no significant clusters of neural activation that predicted treatment response.

Despite the lack of a patient control arm, the authors nevertheless managed to establish that changes in fronto-parietal networks associated with CBT were treatment specific, and not an effect of time. They accomplished this by demonstrating persistence of elevated task-related frontal and parietal activation across the two time points, which was linked to increased anxiety in a separate, untreated adolescent sample at temperamental risk for anxiety. They also included an age-matched healthy comparison group to document alterations in neural functioning across time points, model the effects of time, and assess reliability of the dot-probe task conditions across these time points.

Role of Fronto-Parietal Networks in Pediatric Anxiety Disorders

The authors interpret the “normalizing” of fronto-parietal network activation as an indication that anxious youths became more efficient in engaging cognitive control networks after CBT. This is plausible, considering a recent review reporting normalization of prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortical regions associated with anxiety symptom improvement following CBT in youths (

5). These neural networks are also recruited when restructuring negative thoughts or reappraising negatively charged situations—core cognitive components of CBT. It is unclear, however, whether these patterns of change in neural activation would be different in those who responded to treatment (vs. nonresponders) since the authors did not test the group-by-time-by-response interaction, likely because of limited statistical power. Although there seemed to be some improvements in performance (i.e., faster reaction times) associated with treatment in the anxious group, it is unclear whether change in performance was linked to the decrease in fronto-parietal activation. Given evidence that age-related decreases in prefrontal recruitment (

6) from childhood to adolescence parallel improvement in performance (

7), demonstrating associations between decreases in fronto-parietal activation and improved behavior would provide stronger support for the interpretation of improved efficiency in engaging cognitive control with CBT (

8).

If CBT does indeed help youths become more efficient in engaging cognitive control networks, it is puzzling that activation in subcortical regions (i.e., amygdala) remained unchanged with treatment, considering that another core component of CBT involves extinction processes through guided exposure to increasingly anxiety-provoking situations. Perhaps the effects of change in subcortical activation are small and could have been detected using an fMRI task that included more motivationally salient stimuli than the ones used in this study (i.e., analyses were performed across threat and neutral trials to improve statistical power). It is also possible that changes in cortico-amygdala circuitry can be detected only later, once youths have practiced successfully approaching (rather than avoiding) anxiety-provoking situations or when connectivity between cortical and subcortical regions have matured.

Regarding treatment response, anxious youths did show reductions in anxiety symptoms, as measured by the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale, and improvement in functioning, as measured by the Clinical Global Impressions improvement scale, yet no pattern of activation predicted such improvements. This is in contrast to a 2021 study published in the

Journal documenting heightened activation to reward in corticostriatal regions associated with treatment response among 9- to 14-year-olds diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (

9). Using a randomized controlled trial design (CBT vs. active child-centered therapy), Sequeira et al. (

9) showed that greater response to monetary wins versus losses (similar to the healthy comparison group) in a region of the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex extending to the nucleus accumbens was associated with successful treatment response among early adolescents with anxiety disorders, regardless of treatment type. Interestingly, Sequeira et al. did not find any mediating effects of quantity or quality of exposures during CBT on the associations between neural activity and treatment response. Thus, it remains unclear what patterns of neural function may be associated specifically with response to CBT in unmedicated youths with anxiety. One strategy to address this issue may be to improve our prediction models by going beyond standard univariate analysis of fMRI data and using advanced multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA) techniques (

10). Briefly, unlike univariate analyses, which involve averaging the varying signals in each voxel within a region, these computational methods search for information in the patterns of neural responses across voxels. Such patterns could thus be used to predict treatment response at an individual level. These methods offer greater neural specificity, but they have their own set of limitations (e.g., sample size) (

11).

Early Adolescence as an Optimal Developmental Window for Psychosocial Treatment of Anxiety

Findings from the Haller et al. study, in light of translational research documenting the role of prefrontal cortical networks in pediatric anxiety disorders (

12) and their neurodevelopment (

13), urge us to consider the timing of interventions. Because age and sex at birth were included as covariates, it is unclear whether these factors could have played a moderating role in the changes in neural activation associated with CBT. Nevertheless, the age range of the study sample falls within early adolescence, a developmental period when prefrontal cortical networks and their connections with emotion-related subcortical regions begin to specialize (

8), along with a cascade of neurobiological changes (e.g., neural excitation/inhibition balance) that shape the plasticity of these networks (

13). Early adolescence, with the onset of puberty, is a period of transition from childhood to adolescence, when youths have an increased desire for autonomy, agency, and self-determination (

14). In addition to significant physical and neurodevelopmental changes, early adolescence is characterized by changes in socio-affective learning and motivational flexibility (

15), which is why we believe it is the ideal (or critical) period to harness the potential of neural plasticity and motivational learning to effectively change illness trajectories, promote resilience, and improve long-term outcomes (

16).

Conclusions

The Haller et al. study is an important step toward identifying potential neural mechanisms of change associated with CBT in unmedicated youths diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. What could be the next steps that build upon these novel findings? We could start by dismantling the active components of CBT, with pre–post multimodal neuroimaging approaches (e.g., resting-state fMRI, reward processing, functional magnetic resonance spectroscopy) and MVPA techniques, to clarify how to optimize treatments, in general and for specific patient groups. For instance, youths who present with more or less attentional control, generalization of threat to safety cues, and/or response to reward may benefit more from treatment that emphasizes different components of CBT. How can we get the biggest bang for the buck in terms of change with treatment? We need to gain a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of anxiety disorders and underlying neurodevelopmental mechanisms, as these could then serve as targets of treatment. Given the steep rise in anxiety symptoms, especially generalized anxiety and social anxiety disorders, in girls compared to boys during early adolescence, targeted treatments must take into consideration sex-specific neurodevelopmental mechanisms. Finally, we need to consider the developmental period during which CBT is being delivered. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that early adolescence represents an important inflection point during which targeted and neurodevelopmentally informed interventions could have the most long-term impact. Armed with this knowledge, it would thus be possible to test novel hypotheses about when and for whom CBT (or certain components of CBT and/or adjunctive interventions) may be most effective in improving long-term well-being for youths afflicted by anxiety.