One specific element of functioning is work ability. Reducing work disability can reduce indirect costs of schizophrenia and enable patients to be involved in gainful employment and to experience a sense of accomplishment, a structure for daily routine, and the possibility of belonging to a social group through interactions with coworkers (

5). Only scant evidence is available on work functioning from randomized controlled trials of antipsychotics. Of 167 placebo-controlled randomized controlled trials over 60 years, 10 studies measured functioning (

6). Moreover, real-world functioning can hardly be measured in randomized controlled trials, because of their short duration, narrow and nonrepresentative inclusion criteria, and experimental setting. Short duration of follow-up, small sample size, and selection bias can be overcome by the use of data from national registries, which include representative patient cohorts (

7) and follow them for decades (

8). Even in national registries, the impact of antipsychotics on work status among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders has seldom been studied. A Swedish national cohort study in patients with schizophrenia and their parents (

9) showed that long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics were associated with better work function among the parents (i.e., a lower risk of long-term sickness absence for the parents; odds ratio=0.34–0.47) compared with no antipsychotic use in the offspring. Another Swedish national cohort study (

10) in patients with delusional disorder (N=9,076) reported that the risk of work disability was lower during use of clozapine (hazard ratio=0.08), an LAI (hazard ratio=0.44), or oral aripiprazole (hazard ratio=0.52) compared with no use of antipsychotics.

Regarding how long antipsychotics should be continued after the onset of psychosis, the only available evidence on early discontinuation comes from a naturalistic follow-up study of a 2-year randomized controlled trial (

2), and methodological limitations call for cautious interpretation of the study findings (

11). Actually, since there is a close connection between symptoms and functioning, and antipsychotics improve symptoms (

12) and prevent relapse (

13), antipsychotics might be expected to improve work ability. Among other studies (

14,

15), a study following up patients with first-episode schizophrenia for up to 20 years showed that withdrawing antipsychotic treatment <2 years, 2–5 years, and >5 years after the first diagnosis was associated with 112%, 226%, and 628% increased risk of relapse (

1). However, real-world studies investigating the association between antipsychotics and work disability, overall and across different time windows after first diagnosis, are lacking.

Our aim in this study was to measure the effect of oral and LAI antipsychotics on work disability, namely, sickness absence (SA) and disability pension (DP), in a national cohort of patients with first-episode nonaffective psychosis. We hypothesized that taking compared with not taking antipsychotics would be associated with less work disability, using patients as their own controls in order to remove the impact of confounding factors.

Methods

We included in our analysis persons first diagnosed with nonaffective psychosis (ICD-10 codes F20–F29), ages 16–45 years, from 2006 to 2016 in Sweden. Subjects were identified in the first two of the following sources, and data were collected from all: the National Patient Register (including inpatient and specialized outpatient care); SAs and DPs recorded in the Micro-Data for Analyses of Social Insurance; the Prescribed Drug Register (dispensed medications); and the Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labor Market Studies (age, sex, educational level, country of birth, main occupational activity). All registers were linked by each individual’s unique personal identification number.

In Sweden, individuals from the age of 16 with income from work or unemployment benefits are covered by the public SA scheme and can claim SA benefits if their work capacity is reduced by at least 25% due to disease or injury. For employees, the first 14 days of an SA spell are paid by the employer, with the exception of the first qualifying (“waiting”) day, for which no benefit is paid. Thereafter, employees can receive SA benefits from the Social Insurance Agency, and SA benefits are also paid during hospital stays. For unemployed individuals, compensation can be granted from the second day and is paid by the Social Insurance Agency. All individuals 30–64 years of age can be granted permanent DP if their work capacity is permanently reduced due to morbidity. Individuals 19–29 years of age can be granted temporary DP if their work capacity is reduced by at least 25% or if compulsory or upper secondary schooling is not completed in due time. Both SA and DP can be granted full-time or part-time at 25%, 50%, or 75%; SA benefits cover 80% and DP 65% of lost income up to a certain level. Both SA and DP are based on assessments from a physician, after evaluation of work ability.

Exposures

Antipsychotic use was defined as use of medications classified under Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification code N05A, excluding lithium (N05AN01). Specific antipsychotics were categorized with oral formulations separately from LAIs. Medication use was separately modeled with the PRE2DUP method for different antipsychotics and their formulations (see the Methods section in the

online supplement) (

16). We analyzed the four most common second-generation oral antipsychotics in monotherapy (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and aripiprazole), grouped other oral antipsychotic monotherapies into the category “other oral antipsychotics” (including first-generation antipsychotics and clozapine because of relatively low numbers), and all LAIs into the category “any LAI antipsychotic.” Time periods when two or more antipsychotics were used concomitantly were categorized as polytherapy.

Outcomes

The main outcome measure was start of any SA or DP, regardless of level of compensation or diagnoses, which we categorized as any work disability. Only SAs exceeding 2 weeks are recorded for employees. The secondary outcome was long-term SA (>90 days) or DP, excluding shorter SA. Both outcomes mainly consist of SA, but DP was also included, as it represents more permanent work disability and ends follow-up for SA (that is, SA is not possible after DP is granted and the person is not “at risk” of having SA anymore).

Other Measures

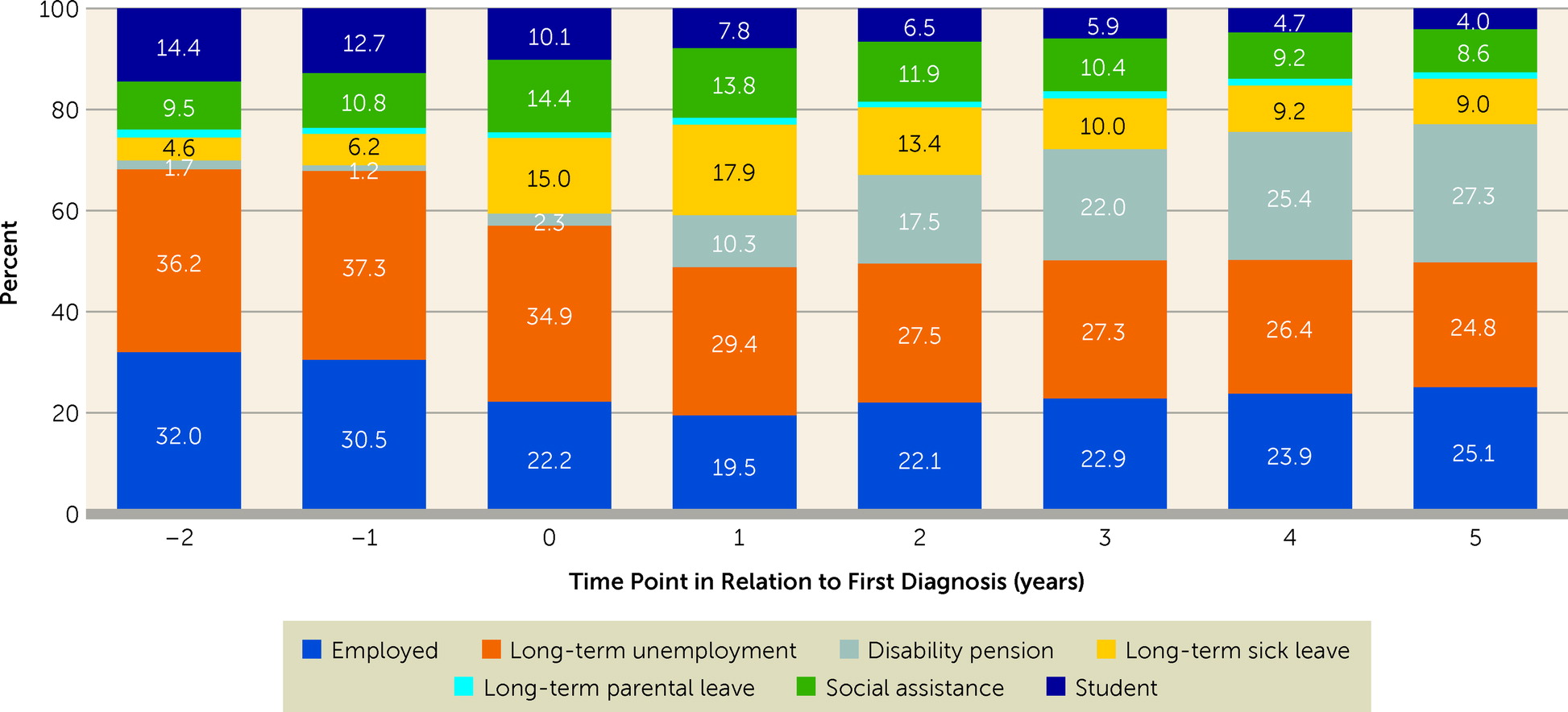

People were categorized yearly based on their main activity or source of income from 2 years before to 5 years after date of first diagnosis (

17). The starting point was categorization by Statistics Sweden, where people were categorized as employed or not employed based on income. Alternative activities and sources of income were evaluated by the number of days of receipt of social security benefits full- or part-time (including SA, parental leave, and DP) and the number of days registered as unemployed; people were assigned to the occupational activity generating income for more than 6 months yearly. Those who were not employed and had received social assistance or student benefits were classified into these categories if those generated more than half of their disposable annual income. These analyses were also stratified by antipsychotic use status during the follow-up. Of these categories, only SA and DP were analyzed as outcome measures.

Study Design and Statistical Analysis

Cohort entry was defined as date of first nonaffective psychosis diagnosis (or discharge from hospital for those who had their first diagnosis recorded in inpatient care). We excluded people who were already on DP at first diagnosis (N=5,144). The follow-up ended at death, emigration, DP, or the end of data linkage (December 31, 2016), whichever occurred first.

SA and DP were analyzed in a within-subject design where each individual acts as their own control (see Figure S1 in the

online supplement). Time periods when antipsychotics were used were compared with time periods when antipsychotics were not used within the same individual. Antipsychotic use or nonuse was the time-varying exposure; a person could contribute person-time to various exposure categories during follow-up. Time periods when the person was not at risk of having an outcome (during ongoing SA) and time periods when exposure status could not be defined (during hospital care) were counted neither as use nor as nonuse of antipsychotics. Because the impact of time-invariant factors, such as genetics, are eliminated by the design, only time-varying factors are adjusted for. These were temporal order of treatments (i.e., the sequence in which each individual trialed different antipsychotics and nonuse, as 1, 2, or 3 vs. >3), time since cohort entry, and time-varying use of other psychotropic drugs (antidepressants [ATC code N06A], mood stabilizers [carbamazepine (N03AF01), valproic acid (N03AG01), lamotrigine (N03AX09), lithium (N05AN01)], and benzodiazepines and related drugs [N05BA, N05CD, N05CF]). Within-individual analyses were conducted with stratified Cox regression models (stratified by individual), yielding adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted in subjects who did not use antipsychotics within 1 year before cohort entry to ensure that they were truly incident cases, as well as in those without SA at baseline (as previous SA increases the chances of having SA again), censoring the first 30 days of each exposure (to control the time period of suboptimal effect of antipsychotics), using SA only as an outcome, and in time periods of <2 years, 2–5 years, and >5 years after cohort entry. In addition to the main comparison (use versus nonuse of antipsychotics), we also compared specific antipsychotics to the most frequently prescribed antipsychotic, oral olanzapine. Moreover, we conducted sensitivity analyses considering only SA >90 days, representing longer-term disability. In addition, to investigate whether antipsychotic use also has an impact on work ability in a population with less severe functional impairment for whom DP was never granted, we conducted a sensitivity analysis within this latter population. Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses in those who were employed at cohort entry. Subgroup analyses by sex and baseline education level were also conducted.

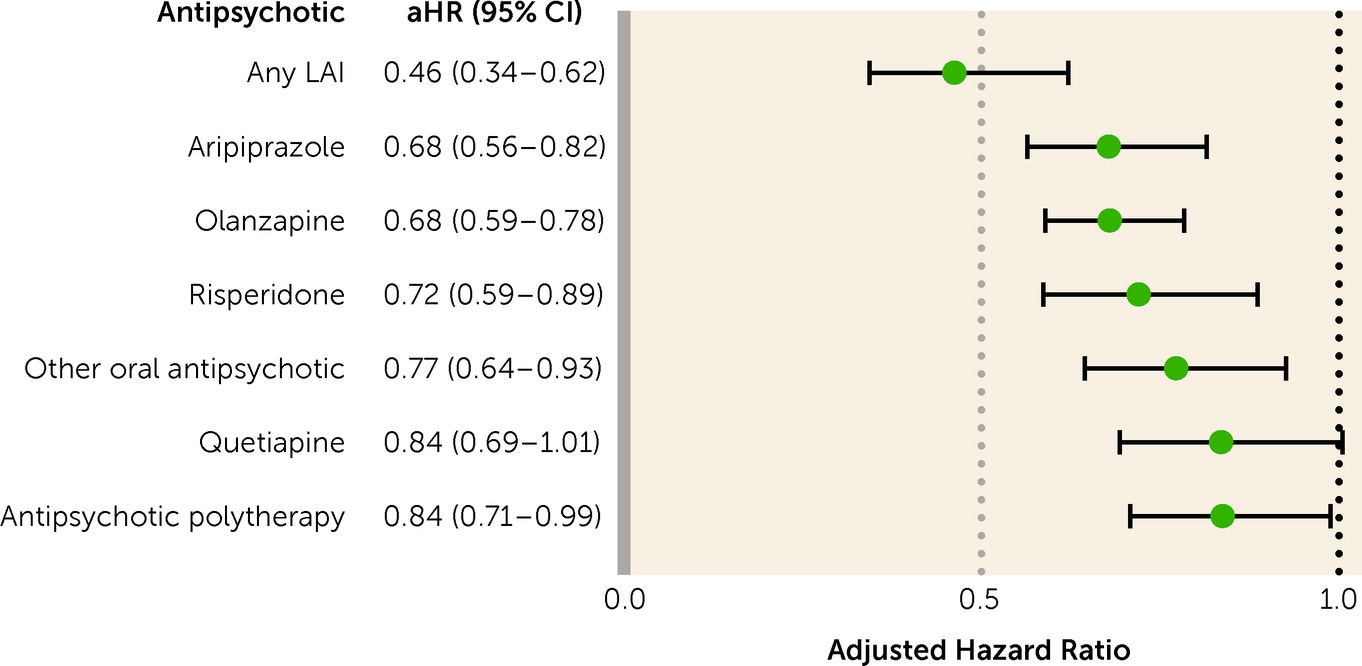

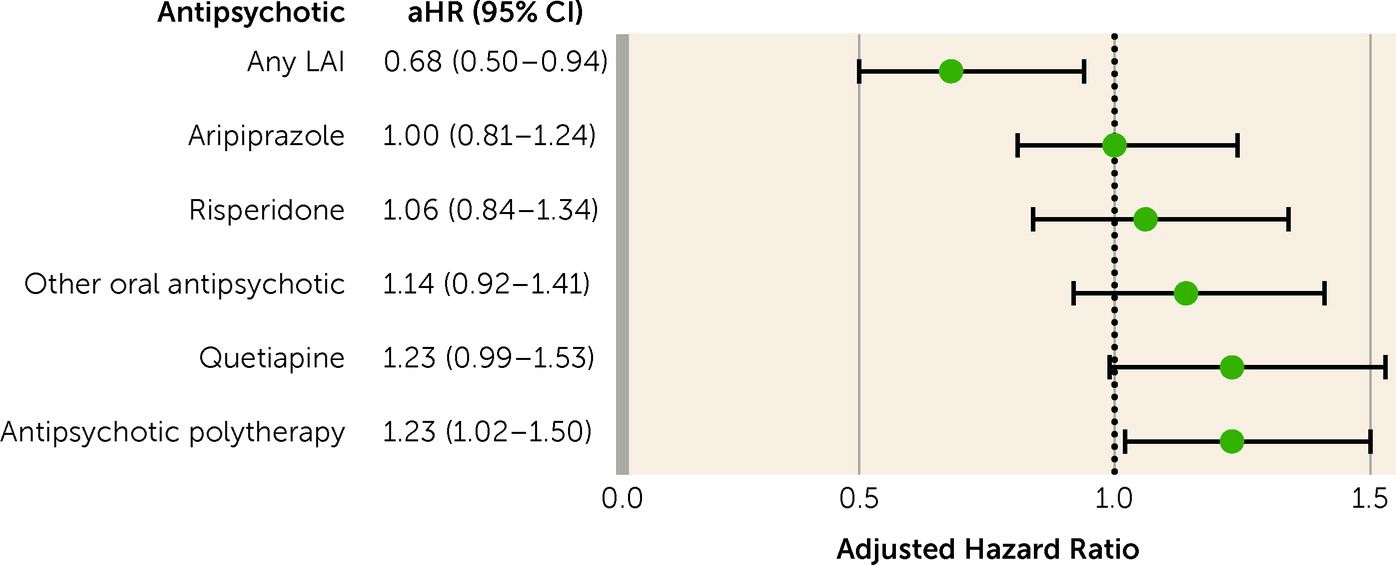

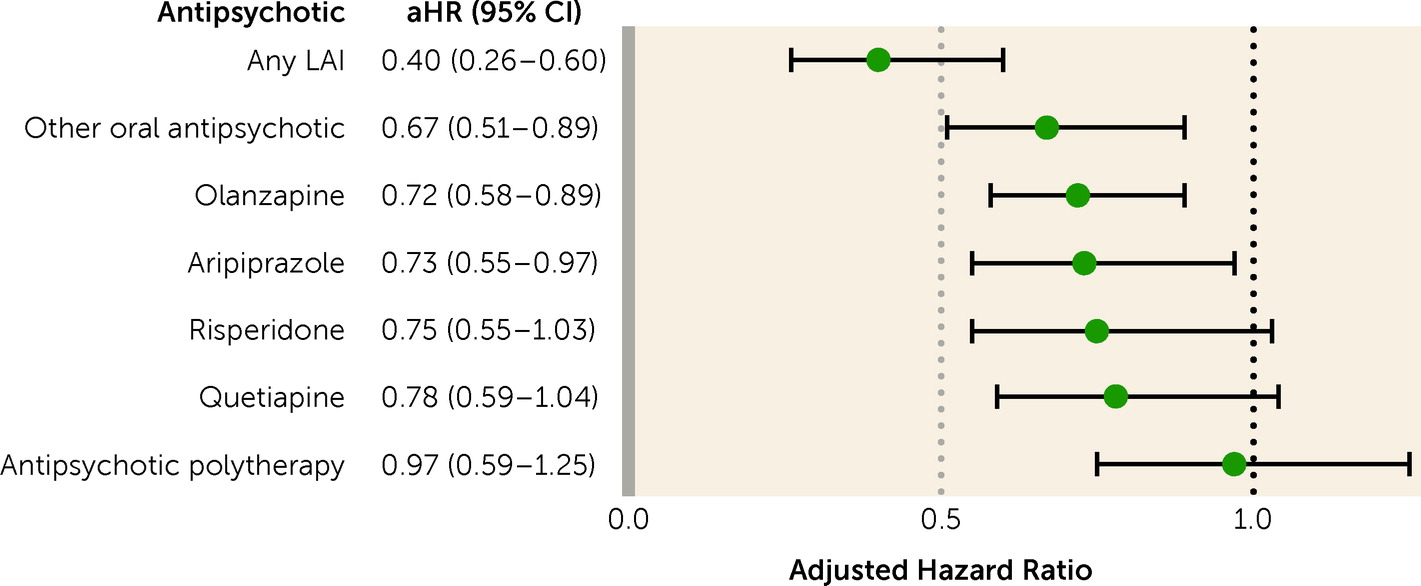

Discussion

The results of this nationwide register-based study show that patients with first-episode nonaffective psychosis had a lower risk of work disability when using antipsychotics compared with periods when not taking them. The risk was >50% lower with LAIs and around 30% lower with oral aripiprazole, oral olanzapine, and oral risperidone. When the inclusion criteria were narrowed, focusing on patients receiving prescriptions for antipsychotics for the first time, removing those with SA at baseline, censoring first 30 days of observation, considering long-term SA or only SA as an outcome, and restricting analyses to milder clinical pictures where DP was never received, the primary results were confirmed. Importantly, the association persisted beyond 5 years after first diagnosis. Also, the results largely held across sex and education level.

The mechanism through which antipsychotics are associated with better work functioning is currently unknown. We hypothesize that antipsychotics exert their action at least partially via their effect on positive symptoms, enabling psychosocial rehabilitation (

18) and/or return to functionality in a sizable subgroup of patients. Indeed, antipsychotics are particularly effective in treating positive symptoms, among other symptoms (

19), and symptomatic remission is a prerequisite of functional recovery for most patients (

20). Interestingly, while positive symptoms are not related to work skills at baseline (

21), positive symptoms are directly associated with poorer work skills at follow-up (

22). More specifically, in a network of clinical manifestations in 740 persons with schizophrenia, everyday skills and functional capacity (indirectly) had the strongest connection with work skills, while positive symptoms were not connected at all (

21). Conversely, when looking at the longitudinal association between positive symptoms at baseline and working skills at follow-up in 618 patients with schizophrenia, a significant association emerged (

22). The results of our study are in line with these latter findings, as reducing positive symptoms with antipsychotics is associated with better functioning at work over time. Our results advance the evidence on the association between continuous antipsychotic treatment and occupational functioning, since they go beyond the indirect evidence of the association between positive symptoms and work skills (

22), linking antipsychotics to an objective and tangible real-world outcome (work disability).

Importantly, the association with work ability was the largest for LAIs. A mounting body of evidence from randomized controlled trials has shown that LAIs are superior to placebo in treating symptoms, and in some aspects superior to oral antipsychotics (

23–

26). LAIs are particularly effective in the early phase of psychosis, according to both experimental and observational evidence (

27–

29). In a cluster-randomized controlled trial involving 489 participants with early-phase schizophrenia across 39 mental health clinics in 19 U.S. states, 19 centers were randomized to once-monthly aripiprazole LAI and 20 to provide treatment as usual. The results showed that aripiprazole LAI was largely superior to treatment as usual, improving time to hospitalization with a hazard ratio of 0.56 (95% CI=0.34–0.92) and a number needed to treat of 7 (

30). In a cohort study of 1,166 patients with ICD-10-defined schizophrenia starting on paliperidone LAI, those with the largest improvement were those with shorter duration of illness (

31).

The present results are also informative about the best clinical choice among oral formulations. Among oral antipsychotics, aripiprazole, olanzapine, and risperidone, which were the oral antipsychotics associated with better work functioning according to the real-world data of this study, have also been found effective in experimental settings in first-episode psychosis, without any clinical or statistical differences between them (

19,

32,

33). Notwithstanding individualized treatment choices that should account for patients’ symptomatic profile, comorbidities, and preferences, the metabolic safety of first-line antipsychotics should be taken into account (

32,

34,

35), given that the premature mortality in schizophrenia is largely due to cardiovascular diseases (

36,

37). In previous studies, antipsychotic polytherapy was associated with a relatively low risk of rehospitalization compared with antipsychotic monotherapy among patients with schizophrenia (

7). However, in the present study, focusing on work ability among patients with first-episode psychosis, antipsychotic polytherapy was not associated with a beneficial outcome compared with antipsychotic monotherapies. This finding may be attributable to the different type of patient population, the different type of outcome, or both.

Continuous antipsychotic treatment in the early phases of schizophrenia is crucial, given the results of this work (i.e., better job functioning), but also in light of the fact that once multiple relapses occur, medications tend to lose some (

14), but not all (

15), of their efficacy in preventing relapse compared to the larger effect they have in the early phase of the disorder. Our results show that the association between use of any antipsychotic and lower risk of work disability remained the same beyond 5 years after cohort entry. This result is of clinical value, as in addition to our previous results from a Finnish nationwide cohort (

1), it is the first real-world study providing evidence that might discourage antipsychotic discontinuation even 5 years after diagnosis of a nonaffective psychosis. This finding can provide useful information for clinicians, patients, and families, as well as guideline developers, given that guidelines vary in their recommendations. For example, in a systematic review of English-language schizophrenia practice guidelines, 17 of 19 (89.5%) guidelines commented on the treatment of first-episode patients (

38). Of these, one guideline each recommended antipsychotic treatment for 9–12 months, 12 months, or 18 months; two guidelines recommended 1–2 years; three guidelines recommended at least 2 years; and another two guidelines recommended continuing antipsychotic treatment after resolution of first-episode symptoms but did not recommend a specific duration of therapy. Furthermore, only five (27.8%) of the reviewed guidelines recommended LAIs for first-episode psychosis, although work disability was averted the most by use of LAIs in this nationwide cohort.

Strengths of our study include a nationwide sample of patients with first-episode nonaffective psychosis and follow-up of their medication use and sickness absence and disability pension through registers. For both sickness absence and disability pension, a medical certificate is necessary. Particularly in the process for deciding on whether a disability pension will be granted, a series of medical assessments is carried out. The study therefore uses data on medically certified sickness absence or disability pension, and not self-rated data. Moreover, the data used for this study are based on payments from the Social Insurance Agency, which undertakes thorough assessments of claimants. There is therefore a twofold rigid control of these outcome measures, making the data highly reliable. All residents of Sweden are covered by the social insurance scheme. Antipsychotic use modeling was conducted with the validated PRE2DUP method and was based on medications dispensed from pharmacies (

16). We utilized a within-individual design, which minimizes selection bias by comparing different exposure periods within the same individual. As the impact of time-invariant factors is eliminated by the design, we adjusted for time-varying factors, which were time since cohort entry, temporal order of treatments, and time-varying use of other psychotropic medications. Finally, the results were confirmed across several sensitivity analyses.

However, limitations of our study also call for cautious interpretation of the findings. First, we did not have information on other possible nonpharmacological treatments, such as vocational rehabilitation, as well as other within-subject factors that might change over time (e.g., alcohol use) which may have affected the ability to work. Only individuals who experienced the outcome event and had variation in exposure contributed to within-individual models. Also, the results on work disability are generalizable only to socioeconomic and health care systems resembling those of Sweden. Register data also do not indicate the severity or fluctuation of symptoms over time. Since medications are typically restarted when the symptoms get worse, it is probable that the beneficial effect of antipsychotic treatment is underestimated. However, this possibility was addressed in sensitivity analyses censoring the first 30 days of exposures, representing the period of high symptom levels before the full pharmacological effect has been reached, resulting in lower adjusted hazard ratios. Furthermore, data on sickness absence were not available from the first 14 days of a sick leave period among employees. Still, periods related to mental disorders are known to be considerably longer than 14 days (

39), and sensitivity analyses censoring the first 30 days also corrected for this timing issue. The associations also remained when we restricted analyses to long-term sickness absences (>90 days). Of note, this sample included a heterogeneous set of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. While this is a limitation in terms of specificity, it is also a strength in terms of generalizability. Also, the nonsignificant findings for polytherapy may have been a result of confounding by indication—that is, with periods with polytherapy indicating more severe clinical presentations that did not respond to monotherapy. As in all register-based studies, we cannot be sure whether dispensed medications have been taken as instructed. However, blood level analyses have shown that our drug use modeling method determines the actual medication use rather accurately (

40). Finally, this study does not account for dose-response relationships, which together with time consequentiality and plausible mechanism are needed to infer causality.

Taken together, the results of this study support the hypothesis that antipsychotic treatment might be continued for at least 5 years when considering work disability, and LAI formulations in particular. We acknowledge that this work needs to be considered in the context of broader evidence on the effectiveness and safety of antipsychotics to make recommendations on the need for long-term treatment, and also that more studies are needed to investigate the role of each specific LAI. Improving work ability is possible, and continuous treatment with antipsychotics, preferably LAIs, might play a role in preventing work disability in the early illness phases in individuals with nonaffective psychosis, beyond 5 years from first diagnosis, minimizing progression to disability pension and chronicity, in the context of an informed and shared decision-making process between patient and physician.