This book is intended to help an array of behavioral health stakeholders to better understand and improve the value of psychiatric care and, more broadly, health services in general. As will become clear in subsequent chapters of this book, emotional health and physical health are tightly intertwined, and the systems and interventions that address health issues in the population will affect both of these conditions. In seeking value from our systems of care, we will explore in this book a wide variety of complex topics, such as health care financing, prevention, clinical practice, and workplace wellness. But first, we must begin with a fundamental question: What is value? How is it defined? Who should define it? How can it be measured?

Although there are multiple formal approaches to defining and measuring value in health systems, they can all be distilled to the simple core definition of outcomes divided by cost (

V = outcomes/cost;

Porter 2012).

Value is sometimes referred to as cost-effectiveness or colloquially as getting the “biggest bang for the buck.” In a broad definition of value, cost may include time, money, social impact, and other resources that may be direct (monetary) or indirect (social disruption) in nature. This determination is often complicated when there is disagreement about what the best outcomes are. Key stakeholders—providers, purchasers, suppliers, payers, and patients/consumers—may deem different outcomes important. Disagreement about value is primarily a disagreement about which outcomes are most important and whether or not the resources necessary to achieve them can be justified. Therefore, whoever has the power to decide which outcomes will define success holds a significant amount of influence.

Another, less tangible but no less important, concept of value has more philosophical and soul-searching implications. All individuals have personal “values” related to beliefs and customs (i.e., kindness, power, security). Communities or organizations may have shared values (i.e., individualism, conservation, acquisition), which may extend to entire states or nations. These “values” will influence what outcomes a particular stakeholder group will choose or prioritize. For example, many of those who go into health care have a desire to make meaningful contributions to society. If recovery-oriented (person-centered, collaborative) care is selected to improve the lives of the people in the population, those involved will want to ensure that the care is being delivered consistently and comprehensively. They will choose outcomes that reflect well-being, such as client satisfaction, independent living, or employment. Another stakeholder, such as an insurer or other payer, may be motivated by profit. The outcome they choose might be reduced use of expensive services or products, such as inpatient care or expensive medications.

In many cases there are “social values” that almost all constituents of the community agree upon, such as reduced violence, incarceration or homelessness, or increased employment, nutrition, or education level. Even though these outcomes are agreed upon, the means for achieving them, as well as the acceptable level of cost (both direct and indirect) associated with any proposed solutions, may be controversial. An example of these conflicts might be the outcome of reduced gun-related violence. For some members of the community, an inexpensive solution might be restricting or banning the sale or private ownership of guns. To other members, that solution is unacceptably costly in terms of personal rights and self-protection; they might propose better gun safety education and further arming responsible members of society, which will be an unacceptably ineffective solution to the first group. These controversies are the meat of political discord and often stand in the way of progress toward these common interests.

Although stakeholders will have different motivations, regardless of their personal values, they will want to set goals and to know to what extent they are achieving them and at what cost. Ideal solutions to an identified opportunity to increase value will allow all stakeholders to improve their conditions. Any useful discussion of enhancing value must define quality through a consensus of stakeholders. Finding indicators of quality and cost parameters that everyone can agree upon can be very challenging, but when they are discovered, they enable an objective assessment of the value everyone is seeking. In health care, creating accountability by measuring adherence to the indicators of quality that are selected, and establishing acceptable expenses for the methods used to achieve them, will allow systems to move toward greater value in the services and interventions they provide. This will benefit both the health of the organizations and the individuals providing care, giving meaning to the hard work put in day after day, and the populations they serve.

In this chapter, we provide an overview of current approaches to defining and paying for value in health care and describe methods for measuring and improving behavioral health outcomes. We conclude with a discussion of the challenges and potential for future advancements in the measurement of quality, cost, and person-centered outcomes. Subsequent chapters delve into the details of creating, financing, and maximizing value. We hope this opening chapter will provide a foundation to help the reader keep sight of the ultimate goal, which is to build sustainable models of care that improve the health and well-being of populations and communities.

Cost of Mental Illness and Substance Use

In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that mental health and substance use disorders accounted for a loss of 183.9 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), or 7.4% of all DALYs worldwide (

Whiteford et al. 2013). Despite a relatively low contribution to overall years of life lost, mental health and substance use disorders are the leading cause of years lost to disability worldwide, with over 75% stemming from depression, anxiety, and illicit drug and alcohol use. Notably, the burden of mental health and substance use disorders increased by 37.6% between 1990 and 2010, an increase that was largely attributable to population growth and aging (

Whiteford et al. 2013). These estimates are likely conservative; because of a variety of factors (including the exclusion of personality disorders from disease burden calculations), the burden of mental illness may be underestimated by almost one-third (

Vigo et al. 2016).

In the United States, health spending is expected to grow at an average rate of 5.5% per year between 2017 and 2026, approximately 1% faster than the average expected growth in the gross domestic product (GDP). As a result, health spending as a percentage of GDP is expected to rise from 17.9% in 2016 to 19.7% in 2026, reaching $5.7 trillion annually (

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2018b). The United States spends the most on health care from a per capita basis than any other nation in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), at almost 2.5 times the average among the 35 member countries, and 25% higher than the next highest spending country, Switzerland (

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2017). Despite the higher level of spending, the people of the United States, on average, do not appear to enjoy improved access or quality on several metrics. For instance, the United States has the second highest rate of patients skipping physician consultation because of cost (22.3%) and by far the highest rate of patients forgoing prescription medication because of cost (18%), although wait times are less of a concern compared with some other OECD countries. From a quality metric perspective, the performance for the United States is mixed, with some metrics, such as 30-day mortality after acute myocardial infarction, being middle of the pack, and others, such as number of admissions to hospital for an exacerbation of congestive heart failure, trending toward the higher end. Even with high rates of spending, the United States does not have the best outcomes. Despite the prevalence and growing availability of evidence-based psychiatric treatments for mental illnesses, stigma at the individual and system levels plays a complex role in creating barriers to care at multiple levels (

Corrigan et al. 2014). In addition to the direct costs of care provision, it is likely that many costs associated with mental disorders are indirect, including costs incurred from reduced labor supply and earnings, public income support payments, and consequences such as homelessness and incarceration (

Insel 2008). With an emerging focus on mental health and concerted efforts to destigmatize mental illness, it is time for patients and providers to develop quality frameworks and demand value in mental health care.

The health care industry is facing many challenges in the United States. With increasing expenditures as compared with other high-income nations, there is no bigger challenge than reducing costs of services (

Anderson et al. 2003). One way to reduce costs is to provide accountable or value-based care. As mental health providers adapt to these challenges, they have to face the daunting task of coming up with ways to measure quality, cost, and benefits, and thus defining value in mental health care provided to consumers.

Health care costs in the United States are driven in large part by the high costs of services in acute care facilities, expensive pharmaceuticals, and administrative costs, primarily in medical settings (

Papanicolas et al. 2018). A 2015 report on utilization of Medicaid recipients noted that about 20% of the members have a behavioral health diagnosis but that this cohort accounted for 50% of total Medicaid expenditures (

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission 2015). Thus, when defining the value of mental health services, providers and policy makers need to assess the value of services in the interface between physical health and mental health. Mental health can cause significant effects on recovery from somatic illnesses; this has been widely studied in relation to access to care, compliance with treatment, and response to treatment. Patients with moderate to severe mental illness have a higher prevalence of physical comorbidities (

Parks et al. 2006). Mental illness and substance use comorbidities are also related to higher total cost of care. These findings are not unique to the United States. In the United Kingdom, the National Health Services has studied and confirmed high costs related to mental health comorbidities in patients with chronic medical illnesses (

Naylor et al. 2016). A landmark U.S. report commissioned by the American Psychiatric Association (

Melek et al. 2018) highlights an opportunity for significant savings if comorbid psychiatric conditions are effectively treated in individuals suffering from chronic medical conditions. Using data from insurance claims, the authors reported on total health care costs of individuals suffering from chronic conditions in cohorts with and without comorbid mental health and substance use conditions. Individuals identified as having comorbid conditions were noted to have significantly higher costs. Furthermore, it was noted that the increased costs were related to expenditures for treating physical illnesses.

There is growing acknowledgment of social determinants of health and their effect on health care outcomes and costs. WHO’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health has defined social determinants of health as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age” (

www.who.int/social_determinants/en). According to a national study on the modifiable factors that can affect health outcomes, such as life expectancy and quality of life, clinical care accounted for only 16% of the outcomes (

Anderson et al. 2003). Other factors, such as socioeconomic status and health behaviors, are deemed much more influential in affecting the health of communities (

Hood et al. 2016). As the awareness of social determinants of health grows, multiple stakeholders are starting to address them and at times are coming together to improve conditions in our communities to promote healthy behaviors and quality of life.

As part of New York State’s Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment program, large health systems and community-based organizations collaborated to develop programs to address unstable housing and food insecurity (

Feliciano and Romanelli 2017). Medicaid plans have introduced initiatives to screen for social determinants and reimburse for some social interventions (

Bachrach et al. 2018). With regard to seeking value in these efforts, an emerging theme is to how to leverage improvements in social determinants of health and align them in value purchasing arrangements. This can be both a welcome change and a challenge for mental health delivery service organizations. Although the increasing focus on social determinants of health is relatively new to both payers and large health systems, many mental health service delivery organizations have been contributing to this work for decades. The challenge lies in measuring work and effort in nontraditional sectors and quantifying its value; this will require investment in a robust infrastructure around use of data analytics to capture and properly attribute the benefits of the work done outside the traditional health care delivery model. Social determinants of health are considered in greater detail in

Chapter 4, “Social Determinants of Health.”

The broad trend of consolidation in the health care industry has increased our ability to invest in large-scale programs. Growth of technology has been another catalyst in bringing change to traditional ways of providing mental health care. Some of the new initiatives in this regard have been in areas of integration of mental health services with primary care, as well as wider implementation of electronic health records, digital therapy tools, and telepsychiatry. These new offerings bring with them challenges of developing models for reimbursement in the existing fee-for-service payment methodology. Hopefully, the move toward value-based payments will align incentives with models for innovative solutions that promote accessible and high-quality mental health care.

Current Approaches to Maximizing Value

There are multiple established value-based strategies that seek to maximize outcomes and reduce associated costs. To better understand these varied approaches, one needs first to consider the stakeholders within the health system who have an interest in these outcomes and associated costs (

Allen et al. 2017):

•

Providers, such as physicians, hospitals, and health systems, facilitate the delivery of health care services.

•

Purchasers include employers and government.

•

Suppliers include pharmaceutical corporations and medical equipment or specialty vendors.

•

Payers are the commercial and publicly available insurance plans.

•

Patients/consumers are the intended recipients of health care services.

Although the interests and desired outcomes for each stakeholder group may overlap, at times they might stand in opposition to one another. Established value strategies attempt, in various ways, to address the needs of each stakeholder. We explore some formal value strategies—value-based insurance design (V-BID), cost-effective analysis (CEA), value-driven population health (VDPH), and the Triple (or Quadruple) Aim—to broaden the understanding of value in mental health services.

Value-Based Insurance Design

V-BID is an approach to cost sharing between payer and service users that attempts to balance costs associated with a specific intervention with the expected outcome (

Chernew et al. 2014). Because almost all health-related interventions have associated risks in addition to potential benefits, clinicians and patients typically weigh these factors when making a decision about whether to proceed. Additionally, the risks and benefits will vary according to each patient’s individual clinical situation. In traditional insurance reimbursement systems, when accessing a service, patients may need to make a copayment, the amount of which is generally constant per service and does not take patient variables into account. V-BID attempts to factor the clinical outcomes of the intervention or service into the copayment, such that services that provide the greatest overall benefit for the health of a population (i.e., preventive or primary care services) would require a lower copayment from patients who receive them, whereas services that have limited benefit for the health of a client or overall population (i.e., cosmetic surgery or life-sustaining interventions at the end of life) would have higher copayments attached. V-BID insurance plans attempt to recognize clinical nuances of specific situations and to take into account that the benefit of an intervention depends on both patient and provider factors, including where and when the service is delivered in the course of the disease process (

Fendrick and Chernew 2017).

High-deductible health plans are another way that payers attempt to share costs with patients and discourage the overuse of unnecessary services. These plans, however, may also discourage the use of necessary services, thereby increasing the rate of cost-related nonadherence to evidence-based services. For example, a study reviewing the effect of these plans on diabetes mellitus management found that low-income patients experienced statistically significant increases in the number of visits to the emergency department for preventable acute complications of diabetes mellitus (

Wharam et al. 2017). High-value health plans, predicated on V-BID, make use of low deductibles and copayments for the proactive management of chronic diseases while requiring higher deductibles for services that are perceived as lower value. This approach attempts to control costs and improve outcomes through better disease management, requiring less high-expense tertiary care. Insurance can be tailored to encourage specific behaviors in persons with chronic diseases. For example, patients with diabetes mellitus would have a low or no deductible for routine eye examinations, given the relatively higher risk of developing diabetic retinopathy. Patients who do not have diabetes mellitus would have a higher copayment or deductible for a similar eye exam, because it is less likely to have a significant benefit. Clearly, the use of variable cost sharing based on evidence of which practices are most likely to be beneficial to a particular person would encourage prevention and reduce the usage of expensive acute care resources for patients further along the disease continuum.

Several barriers exist to the implementation of V-BID (

Chernew et al. 2014). From a payer or purchaser perspective, the reduction in copayments for higher-value and preventive services may result in increased access to these services, and thereby costs. Although in theory this could result in lower costs over the long term, it may result in increased costs in the short term. In addition, the selection of high-value services is predicated on two key factors: medical evidence to identify high-value interventions, and methods of determining which patients would receive the most benefit from them. Although there are certainly evidence-based treatments within mental health services, there is insufficient research to effectively identify or distinguish high- and low-value services. Data on patient characteristics and systems to manage these data are necessary to determine which patients would qualify for which services. Personal health information on risk factors and past medical history would be necessary to understand which patients would benefit from which services, and data infrastructure would be needed to store and meaningfully interpret this information.

Cost-Effective Analysis

CEA is an analytic tool that attempts to compare the costs and effects of alternative services for the same health concerns. It acknowledges the limited availability of resources and seeks to prioritize the achievement of the best health possible within those limitations (

Neumann and Sanders 2017). CEA uses a ratio of incremental cost to incremental effect, and is differentiated from other cost analyses by the use of health outcomes as a measure—such as the use of DALYs or quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), cases of disease prevented, or years of life gained—as opposed to monetary measures (

Sanders et al. 2016). CEA is applied by payers, suppliers, and providers as part of a focused inquiry into potential alternatives to determine which option would deliver the best health outcomes at the lowest cost.

QALYs represent a way of measuring quality and quantity of life and are calculated by multiplying a quality-of-life score (commonly referred to as the utility value) by length of time (

Prieto and Sacristan 2003). Perfect health is assigned a utility value of 1, death is 0, and the full range of human health experience lies in between. For example, a year of life lived in perfect health is equivalent to 1 QALY, and a year lived in less than perfect health would be worth less than 1. By combining gains from improved quality and quantity of life into a single measure, QALYs can then be calculated for different treatments and can be used to compare cost-effectiveness. For example, suppose treatment A and treatment B are both used to manage condition X. Treatment A provides 3 years of perfect health (3 QALYs) and costs $50 per treatment, and treatment B provides 2 years of perfect health (2 QALYs) and costs $100 per treatment. Treatment A has a cost per QALY of $16.70, whereas treatment B has a cost per QALY of $50, making treatment A more cost-effective in this oversimplified illustration.

Several techniques have been established for measuring QALYs and determining the quality-of-life score for various conditions, including the visual analogue scale, the standard gamble, and the time trade-off (

Knapp and Mangalore 2007). In the visual analogue scale, participants rate a state of ill health between 0 (worst health or death) and 100 (perfect health). The standard gamble is rooted in the

von Neumann and Morgenstern (1944) theory of preference measurement. In the standard gamble method, individuals are given a choice: they can either remain in a state of poor health for a defined time period or choose a medical intervention that has a certain probability of either restoring them to perfect health or ruining their health. The probability is varied until the individual has equal preference for both options, and the utility value is determined from this metric (

Bleichrodt and Johannesson 1997). In the time trade-off method, respondents are asked to decide between staying in a state of ill health (reduced utility) for a period of time, or returning to perfect health with a shorter life expectancy. The time is varied until there is no preference, and the utility value is calculated from this measure. In addition, established tools are available in the literature that can be used to generate QALY measures based on multiple health attributes (

Knapp and Mangalore 2007).

The concept of a QALY is not without controversy. In studies involving mental health, QALYs have been used as an outcome measure with mixed success; it is suspected that some of the aforementioned methods of measuring QALYs and utility scores may be more effective for physical rather than mental health and that standard QALY-generating tools are not sensitive for the symptoms, functional issues, and quality-of-life concerns relevant to people experiencing mental illness (

Knapp and Mangalore 2007). Even when QALYs are appropriately measured, health systems must address “willingness to pay.” In health care, this amounts to determining how much is appropriate to spend per QALY gained by a particular treatment. In the United States, many cost-effective analyses use a benchmark of $50,000 per QALY in the assessment of cost-effectiveness for medical interventions. The roots of the establishment of this number are unclear and thought to stem from a decision in the 1970s to mandate Medicare coverage for patients with end-stage renal disease, because the cost-effectiveness of dialysis was approximately $50,000 per QALY at the time (

Grosse 2008). However, determining a reasonable cost-effectiveness threshold for the QALY is a controversial and challenging process that necessitates an open discussion of the monetary value of human existence.

Part of the disagreement over the usefulness and validity of the $50,000 threshold derives from its adoption in the 1990s and the fact that inflation has not been taken into consideration since then. Some organizations, including WHO, have suggested that a threshold of two to three times the average per capita annual income may be more realistic; in the United States, this figure would be approximately $120,000–$180,000 based on a per capita average income of $60,000. The United States has legislated, through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, against the explicit use of cost-per-QALY thresholds, but the usage persists (

Neumann et al. 2014). Although a general threshold may be helpful as guidance for policy and decision makers, decisions about health care spending are complex and contextual. WHO has outlined limitations to the use of an explicit threshold, including the need to consider the spending in the context of other health system needs (

Marseille et al. 2015). Being below the cost-effectiveness threshold alone does not necessarily make a particular treatment option the best one for the overall health of the population. Other factors, such as the health care budget and other pressing health system needs, must be considered. Funding is not infinite, and decisions will still need to be made regarding which interventions to implement, even if multiple interventions are below the threshold. In addition, these thresholds are largely untested. Although social willingness to pay may be a conceptually appropriate way to define

social value, basing a cost-effectiveness threshold on a country’s per capita GDP blatantly discriminates against those who are poor and is an arbitrary threshold that is not usually grounded in evidence of overall social benefit.

Value-Driven Population Health

VDPH is a relatively new approach that combines a theoretical underpinning with management frameworks in an effort to maximize the value of every dollar spent on population health (

Allen et al. 2017). It aims to tackle the concurrent problems of high health care costs and mediocre aggregate health outcomes. It recognizes that contributions from five key stakeholder groups—providers, purchasers, suppliers, payers, and patients/consumers—play a role in the current problems facing health systems, and each group needs to manage outcomes and costs in combination to foster alignment. From a managerial perspective, VDPH provides a system of objectives, measures, and tools designed to improve stakeholder role performance.

Triple (or Quadruple) Aim

The Triple Aim is an approach that defines three key aims that are essential for the improvement of a health system: improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs of care (

Berwick et al. 2008). The approach recognizes that each aim is critical to sustainable health system success and that the three do not function independently of one another. Making change in one may affect the others positively or negatively. For example, reducing the misuse or overuse of a diagnostic test may reduce per capita costs of care and have a negligible effect on population health. Increasing access to publicly funded psychotherapy may improve the experience of care and the health of the population but potentially increase per capita costs. Recently, there has been an increased focus on a fourth aim—improved provider experience—as a missing component of the Triple Aim and something that is essential for sustained health improvement. Over 46% of U.S. physicians report symptoms of burnout, and a principal driver of provider satisfaction is the ability to provide quality care (

Bodenheimer and Sinsky 2014) (

Table 1–1). Care providers and their supporting teams are human. Patients want quality care, and their care teams want to provide it. Physician and staff turnover can lead to disruptions in care and cumbersome searches to find replacements. Provider job satisfaction is critical to the long-term sustainability of health system and care delivery.

Measuring and Improving Quality Outcomes

The scientific approach to quality improvement (QI) in medicine can be traced as far back as Florence Nightingale’s groundbreaking statistical analysis of the relationship between hygiene and mortality among soldiers wounded in the Crimean War in the 1850s (

Kudzma 2006). However, the importance of QI did not come to the full attention of the U.S. health care industry until a series of landmark reports published in 2000–2001 by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), since renamed the National Academy of Medicine.

To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (

Institute of Medicine 2000) exposed the troubling state of American health care, specifically the 45,000–100,000 annual deaths linked to preventable medical errors. A follow-up report,

Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (

Institute of Medicine 2001), concluded that health care lagged other industries in terms of quality and safety by at least a decade and called for a fundamental redesign of the entire health system rather than incremental or piecemeal attempts at addressing the problem. Together, these works heralded a national call to action and laid out a framework for health care to systematically approach quality and safety as a priority.

The

Institute of Medicine (1990) has defined quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (p. 21), and defined safety as “freedom from accidental injury” when interacting in any way with the health care system (

Institute of Medicine 2000, p. 4). It identified six aims to guide health care organizations in their improvement efforts (

Table 1–2).

Building on this work, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) introduced the concept of the Triple Aim in 2008 (

Berwick et al. 2008), and a fourth aim, focused on improving the work life of clinicians and staff, was added in 2014 (

Bodenheimer and Sinsky 2014) (see

Table 1–1). Subsequent work by the IOM, IHI, and other key organizations, such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Joint Commission, and CARF International, has further advanced the field of QI in health care. All have recognized a need to learn from and adapt advances in QI from other high-reliability fields such as manufacturing and aviation. A detailed discussion of applied QI methods (e.g., Plan-Do-Study-Act, Lean Six Sigma) is beyond the scope of this chapter, but these methods are considered further in

Chapter 2, “Evolution of Funding and Quality Control in Health Care.” For the purposes of this discussion, suffice it to say that a fundamental first step for any QI endeavor is the development of measures that reflect the quality of care being delivered. As Sir William Thomson, better known as Lord Kelvin, famously said, “If you cannot measure it, you cannot improve it.”

The Value of Quality Measurement

Quality measurement is often considered a necessary evil that one must undertake to meet regulatory requirements (and to get paid, as value-based contracting gains popularity). When designed and used effectively, however, quality measures reflect something more fundamental: they are the incarnation of value. Value in this context refers to both cost-effectiveness and the personal/social definitions of value discussed in the introduction to this chapter. This multifaceted definition of value is intertwined with the Quadruple Aim. Outcome measurement helps us determine how effectively we are using our resources to provide high-quality care that improves population health. Measuring adherence to personal and social values ascribes meaning and purpose for our work.

Aligning Metrics With Values

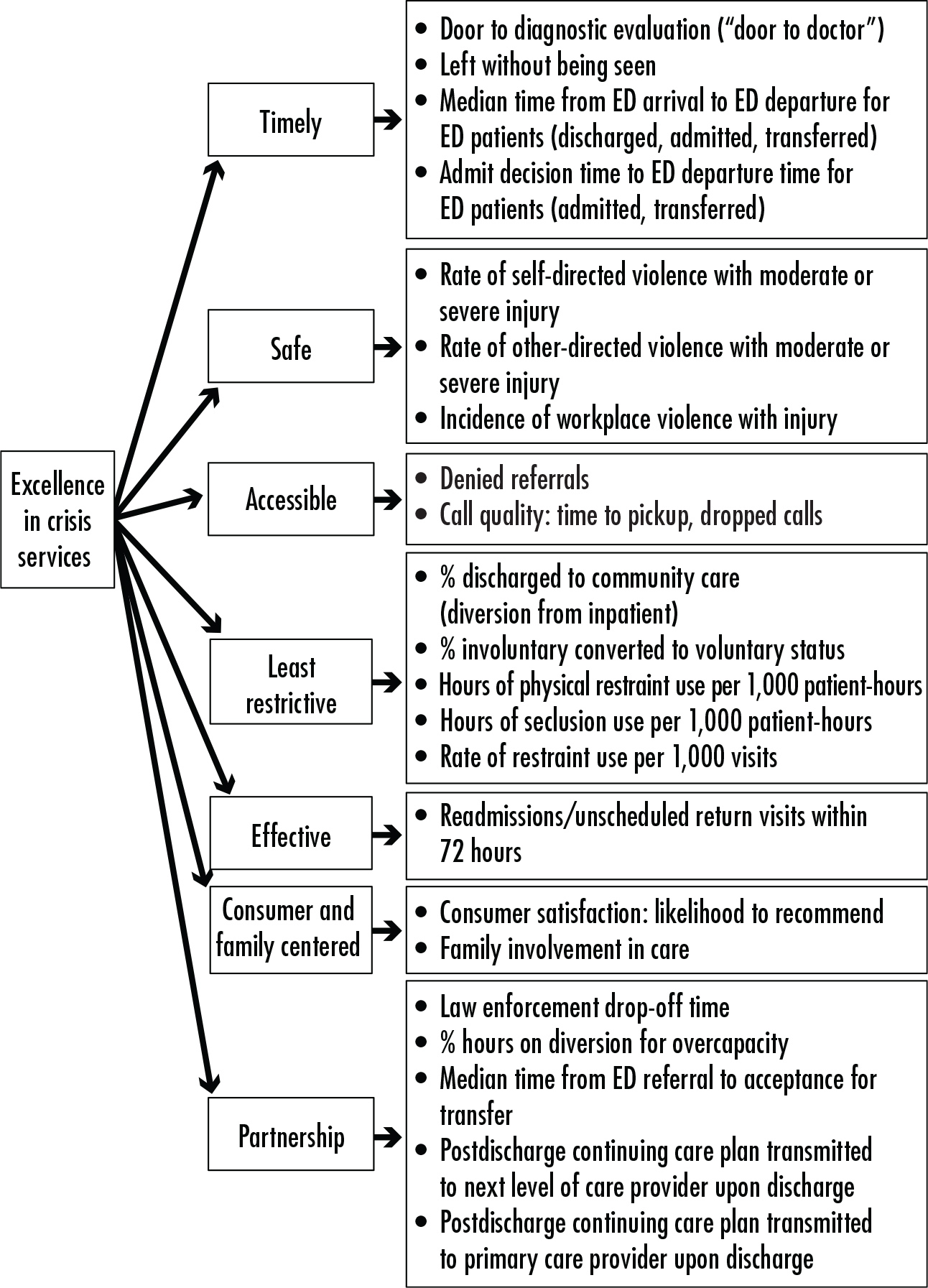

One technique to align quality measures with values is via the adoption of a Critical-to-Quality (CTQ) tree. This tool is designed to help an organization translate what the customer values into discrete measures (

Lighter 2013). This tool has been used in the development of a core measure set for behavioral health crisis services (

Balfour et al. 2016). A CTQ tree begins with a broad customer need. In the example shown in

Figure 1–1, the customers are key stakeholders (providers, purchasers, suppliers, payers, and patients/consumers) and the need is “excellence in crisis services.” This broad goal is broken down into quality drivers that the customer uses to determine whether or not the broader goal is met. In this example, the drivers representing the customer’s values were defined as timely, safe, accessible, least restrictive, effective, consumer and family centered, and collaborative (“partnership”). These are consistent with the IOM’s six aims for quality health care—that it be safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable (

Institute of Medicine 2001; see

Table 1–1)—while also focusing attention on goals unique to the behavioral health crisis setting. The final step is to define measurable performance standards for each driver. For example, measuring the percentage of patients discharged to the community (instead of a higher level of care) reflects performance for the driver “least restrictive.”

Types of Metrics

It is important to understand various types of measures and at what point their application is most effective to support improvement efforts. Dr. Avedis Donabedian—an early pioneer of quality measurement in health care—developed the commonly used Structure-Process-Outcome model (

Donabedian 2002):

1.

Structure: the environment in which care is delivered. Metrics may describe organizational structure, resources, or staffing (e.g., staff-to-patient ratios, presence or absence of on-site psychiatrist).

2.

Process: the techniques and processes used to deliver care. Metrics may describe the use of screening tools (e.g., percentage of patients screened for suicide risk) or the speed with which a specific intervention is completed (e.g., door-to-doctor time).

3.

Outcome: the result of the patient’s interaction with the health care system (e.g., injury, death, quality of life, change in symptom rating scales, readmissions).

Different types of measures are appropriate for different settings and purposes. Outcome measures are the most desirable. However, sometimes it is not feasible to collect outcome data, or it is not within the scope of an organization to change an outcome on its own. In these situations, a process or structure metric is more appropriate.

Considerations for Implementation

Many frameworks exist to inform the selection and implementation of individual quality measures. A simple and straightforward approach, described by

Hermann and Palmer (2003), requires that measures are meaningful, feasible, and actionable. The following list provides some key considerations regarding each of these requirements.

•

Meaningfulness: Does the measure reflect a process that is clinically important? Is there evidence supporting the measure? Compared with other fields, there is a less robust evidence base for behavioral health measures, so we must often rely on face validity or adapt measures for which there is evidence in other settings. When possible, measures should be selected or adapted from items that have been endorsed by organizations that set standards for quality measurement, such as the National Quality Forum, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Most of these organizations maintain online databases of measures available for use or adaptation.

•

Feasibility: Is it possible to collect the data needed to provide the measure? If so, can this be done accurately, quickly, and easily? Data must be produced within a short time frame in order to be actionable. An organization’s quality department staff should be able to spend most of its time addressing identified problems rather than performing time-consuming manual chart audits. With the advent of electronic health records, it is now possible to design processes that support automated reporting, making it feasible to quickly obtain data that were previously too complex or labor intensive to collect via chart abstraction.

•

Actionability: Do the measures provide direction for future quality improvement activities? Are there established benchmarks toward which to strive? Are the factors leading to suboptimal performance within the span of control of the organization to address? For example, a stand-alone behavioral health crisis program is in a position to identify many problems in the community-wide system of care (e.g., lack of housing, ineffective outpatient follow-up after discharge) and can be instrumental in collaborating with system partners to help fix these larger issues (

Balfour et al. 2018). However, the organization’s own core measures must be within its sphere of influence to improve, or else there is the tendency to blame problems on external factors rather than focus on the problems it can address.

Quality Measurement in Behavioral Health

Behavioral health has lagged behind the rest of the medical field in terms of quality measurement. Behavioral health systems have long existed in a silo apart from the rest of the house of medicine, partly due to financing structures. Many behavioral health services are financed by Medicaid and various locally administered funds and are thus beholden to local regulation as much as nationwide federal standards. In both public and private sectors, managed care organizations often “carve out” behavioral health services into a separate managing entity, further leading to fragmentation and silos. Even federally funded behavioral health systems such as Medicare often exclude behavioral health when developing their measurement systems. For example, the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS), a patient satisfaction survey required by CMS for all hospital inpatients, excludes psychiatric inpatients (

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2018a). Similarly, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act provided financial incentives for health care organizations to demonstrate “meaningful use” of electronic health records to improve quality outcomes but did not include psychiatric facilities (

Cohen 2015).

Currently, the most widely used behavioral health measures focus on inpatient psychiatric services, substance use screening, and outpatient depression care. The Hospital Based Inpatient Psychiatric Services core measure set was developed by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and adopted by CMS for its Inpatient Psychiatric Facility Quality Reporting program (

Joint Commission 2019). The measure set includes metrics related to seclusion and restraint use, substance use screening, antipsychotic polypharmacy, and care coordination. The CMS Merit-based Incentive Payment System for physicians includes several measures related to depression screening, metabolic monitoring for patients taking antipsychotics, and coordination of follow-up care (

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2019).

Fortunately, there is increasing momentum to develop additional standards and measures for behavioral health. The Interdepartmental Serious Mental Illness Coordinating Committee, an advisory committee created by the 21st Century Cures Act, recommended that federal quality and measurement initiatives include behavioral health in its initial report (

Interdepartmental Serious Mental Illness Coordinating Committee 2017). The American Psychiatric Association is supporting measure development via the PsychPRO registry (

American Psychiatric Association 2020) and has recently received grant funding from CMS to develop additional behavioral health measures for the Quality Payment Program (

American Psychiatric Association 2018).

The opportunity to guide our own measure development is a pivotal moment for psychiatry. Via the selection and endorsement of measures, professional organizations and regulatory agencies can incentivize improvement in strategic areas of behavioral health care delivery. For example, the increasing focus on the 25-year mortality gap (

Parks et al. 2006) between individuals with serious mental illness and the general population has increased emphasis on the value of whole-person health. This has led to the adoption of measures related to physical health and behavioral health integration. Physical health screening and disease management measures have become increasingly employed in behavioral health settings, and the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics demonstration program includes multiple measures related to preventive care and screening for diabetes and smoking cessation (

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2010). Conversely, measures related to depression and substance use screening are increasingly common in primary care settings, which support the adoption of integrated/collaborative care models and measurement-based care.

An important challenge will be to develop measures supporting the delivery of recovery-oriented care. The

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2012) defines

recovery as “a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential.” Thus, recovery is both a process

and an outcome, a fact that does not fit neatly into the frameworks described earlier in this chapter. However, application of the Critical-to-Quality approach (see earlier subsection “Aligning Metrics With Values”) would focus on the key attributes included in the above definition of

recovery to inform the development of more specific metrics. Improved health, wellness, and reaching one’s full potential can be captured in quality-of-life measures. Self-direction is more complex, but a promising place to start is with measures of consumer satisfaction and shared decision making, both of which have been correlated with better treatment engagement and outcomes (

Joosten et al. 2009;

Lanfredi et al. 2014). Measuring recovery in this way reflects a more holistic concept of value that includes not only

what care we as psychiatrists deliver, but also

how we do so.

Conclusion

As the personal and economic burden of mental illness increases, there is a clear need to understand value in the context of mental health services. As a profession, psychiatry must participate in discussions and decision making surrounding the question of value.

Value can be broadly defined as outcomes divided by costs, but the negotiations surrounding which outcomes are most important and how much should be spent are complex and challenging to navigate. There are multiple facets to value in mental health beyond the quality over cost equation in delivery of services. Mental health conditions are often unrecognized and undertreated in our communities (

Kessler et al. 2005). Improving access—and beyond that, focusing on preventive care—is a new frontier for demonstrating the value of mental health services in our communities.

As noted earlier in this chapter (see “The Cost of Mental Illness and Substance Use”), costs for care are high for patients with mental health conditions because of the high prevalence of physical comorbidities. Thus, as new payment models develop that focus on shared savings programs, we see a great opportunity for increasing value by expanding access and improving the mental health care delivery models. Another area of value that needs further exploration is the interface of social services and health care delivery. Mental health service providers are well suited to guide this work because they have the most experience in working with the biopsychosocial model and have been working collaboratively with social service agencies for decades.

No discussion on improving value is complete without addressing the waste and inefficiencies that exist in the current system. It is estimated that in the United States, about 30% of health care costs are attributed to waste in the system (

Berwick and Hackbarth 2012). Our field needs to analyze the true costs of our practices and invest in the comparative research of effectiveness of various treatment modalities. Among the various areas of waste that have been identified in health care, improving preventive care, enhancing care coordination, and reducing fragmented care are significant areas of opportunity in mental health services.

As experts in mental health, psychiatrists can play a unique role in defining value by working to bridge differences in perspectives between the various stakeholders involved in mental health care. Psychiatrists are often poised at the interface of the major stakeholder groups—providers, purchasers, suppliers, payers, and patients/consumers—and can link the evidence and clinical perspectives to the broader systems organization. The various stakeholder groups may have differing opinions on the outcomes that are most important and what they are worth. Psychiatrists have an opportunity to lead educational initiatives and foster a shared understanding of the biopsychosocial approach to managing patients appropriately. It is critical that psychiatrists remain engaged in administrative processes and focused on leading system change. One must be involved in order to influence, and we psychiatrists can use our collective voice to advocate for systems that deliver high-value care for all.