Chapter 1. An Internist’s Approach to the Neuropsychiatric Patient

Mr. A reported that he had experienced sudden onset of visual hallucinations 1 month earlier. He described the visual hallucinations as a face covered with a white mask that appeared in front of him from time to time. He reported that the face also talked to him and that he heard a male voice telling him that he would be harmed. He reported that he felt that his house was possessed by demons and that they were coming to get him.

What Is Diagnosis?

Cognitive Psychology Approaches to Diagnosis

A Theory of Nonanalytic Reasoning

(1) high-level, precompiled, conceptual knowledge structures, which are (2) stored in long-term memory, which (3) represent general (stereotyped) event sequences, in which (4) the individual events are interconnected by temporal and often also causal or hierarchical relationships, that (5) can be activated as integral wholes in appropriate contexts, that (6) contain variables and slots that can be filled with information present in the actual situation, retrieved from memory, or inferred from the context, and that (7) develop as a consequence of routinely performed activities or viewing such activities being performed; in other words, through direct or vicarious experience. (Custers 2015, p. 457)

Traditions of Medical Analytic Reasoning

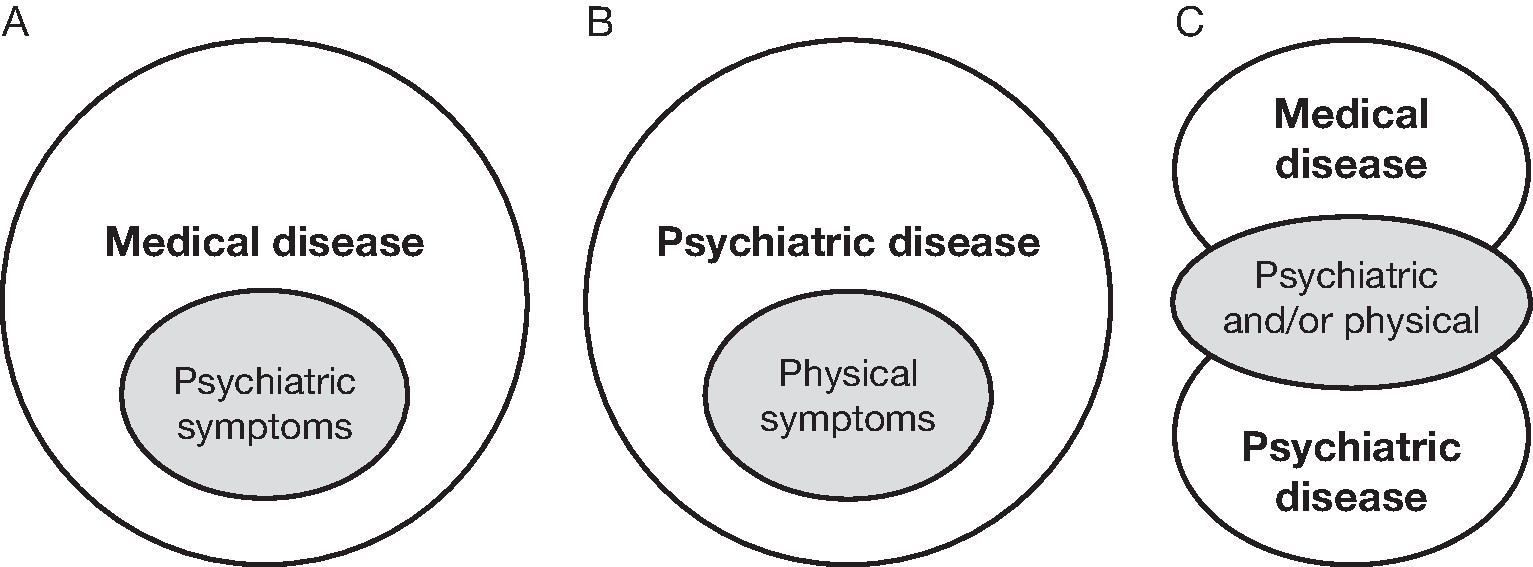

Neuropsychiatric Diagnosis

The Challenge of Medical Causes of Psychiatric Illness

Strategies for Minimizing Medical Misdiagnosis

New-onset psychiatric symptoms after age 45 years or new onset of psychotic illness at any age |

Advanced age (≥65 years) |

Abnormal vital signs |

Cognitive deficits (decreased level of awareness) |

Delirium, severe agitation, or visual hallucinations |

Focal neurological findings |

Evidence of head injury |

Evidence of toxic ingestion |

aAny one of these findings would merit a comprehensive medical examination.

Source. Adapted from recommendation 2 (p. 643) in Wilson MP, Nordstrom K, Anderson EL, et al.: “American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Task Force on Medical Clearance of Adult Psychiatric Patients. Part II: Controversies Over Medical Assessment, and Consensus Recommendations.” The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 18(4):640–646, 2017.

1. Choose a diagnosis based on your intuition or “gut feeling.” |

2. List the findings in the case presentation that support this diagnosis, the findings that speak against it, and the findings that would be expected to be present if this diagnosis were true but that were not obtained in your patient evaluation. |

3. List alternative diagnoses as if your initial intuitive diagnosis had been proven to be incorrect and proceed with the same analysis for each alternative psychiatric and medical diagnosis. |

4. Draw a conclusion about the most likely diagnosis for the case. |

Source. Adapted from “Reflection for the verification of diagnostic hypothesis” subsection (p. 20) in Mamede and Schmidt 2017 |

A Theory-Based Diagnostic Strategy to Reduce Medical Misdiagnosis

Case 1

Case 2

Conclusion

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).