Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, readers will be able to:

•

Define the role of the physician-advocate

•

Provide historical and recent examples of advocacy by physicians

•

Describe why psychiatrists are needed as advocates in this era of rapidly changing mental health care systems

Physicians as Advocates: Defining Advocacy in Medicine

All physicians can be advocates.

In recent years, advocacy as a professional responsibility has begun to gain widespread recognition in the “house of medicine.” In 2001, the American Medical Association adopted the “Declaration of Professional Responsibility: Medicine’s Social Contract With Humanity,” which states that physicians should “advocate for social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being” (

American Medical Association 2001, p. 195). Advocacy is generically defined as “the act or process of supporting a cause or proposal” (

Merriam-Webster 2019). Applied specifically to health care, advocacy can be defined as

the public voicing of support for causes, policies, or opinions that advance patient and population health.

When we consider this health care–specific definition and terminology, we can understand advocacy as a broad term that encompasses a wide variety of actions physicians can take to improve the health of patients and the health care systems that serve them—or fail to serve them. We can define physician-advocates as physicians who strive to enact changes that will be beneficial to patients and crucial to the continued improvement and even survival of our health care systems. Furthermore, physician-advocates consistently strive to act in the best interests and according to the values of the patients, communities, and populations served. Although such advocacy may require that we take stances on political or legislative issues, it does not provide an opportunity for us to express our personal political beliefs (which is more appropriately accomplished by advocating as private citizens). Any stances we take as physicians should reflect our informed medical opinions on how best to advance the health care that our patients receive and the health of the communities in which they live, in accordance with their values and best interests.

Advocacy may not be formally taught during medical training, but it is a ubiquitous part of physicians’ daily work. (New efforts to teach advocacy in psychiatry residency training programs are described in

Chapter 8, “Education as Advocacy.”) For example, a physician may advocate by calling an insurer repeatedly for authorization of health care coverage that has been unfairly denied to a patient or by pointing out discriminatory practices in medical settings against individuals who have mental illness and/or who are members of other historically marginalized groups (

Chapter 5, “Patient-Level Advocacy”). An organizational physician-advocate may join a hospital task force that is aimed at improving care for chronic conditions by assisting with logistical barriers to attending appointments (

Chapter 6, “Organizational Advocacy”). Advocacy at the population level, such as with local, state, and federal governments (

Chapter 7, “Legislative Advocacy”), can spur critical changes to the system of health care. Writing op-eds and posting on social media our professional opinions about health care topics are forms of advocacy (

Chapter 10, “Engaging the Popular Media”), as are educating medical trainees to be attuned to inequities in the health care system (

Chapter 8, “Education as Advocacy”) and producing high-quality research that helps to shape more informed and humane public policies (

Chapter 9, “Research as Advocacy”).

Although we began this chapter with the statement that all physicians can be advocates, as you can see, most of us already are physician-advocates—perhaps without even realizing it.

Psychiatrists as Advocates: A Call to Action

The field of psychiatry is in need of physician-advocates. Mental health disorders, including substance use disorders, affect a large proportion of the U.S. population: an estimated 1 in 5 adults, or 46.6 million people, suffer from mental illness in a given year (

National Alliance on Mental Illness 2019). Among youth, approximately 1 in 5 American adolescents ages 13–18 have experienced mental health problems during their lives (

National Alliance on Mental Illness 2019). In fact, the

World Health Organization (2011) attributes a full 30.9% of the global burden of disease in the United States to psychiatric disorders. Mental health disorders are well known to contribute to decreased quality of life and premature death, including from suicide but also from treatable medical conditions such as cardiovascular disease (

Brown et al. 2010). In addition, the economic cost of mental illness is enormous; the

World Economic Forum (2011) estimates that mental illness accounts for the largest share of global economic burden among noncommunicable diseases.

Despite the prevalence and individual and societal toll of mental illness, less than half of individuals with mental illness received any treatment during the past year (

National Alliance on Mental Illness 2019). Access to care is a pressing issue, especially given the shortage of psychiatrists nationwide and the lack of enforcement of mental health parity laws in many jurisdictions (

Douglas et al. 2018). Stigma against mental illness, including substance use disorders, also looms large and prevents many individuals from seeking necessary treatment.

Moreover, patients with mental illness may be less able to effectively advocate for themselves than are patients with nonpsychiatric diagnoses. This is in part because their psychiatric symptoms may interfere. For example, they may be too disorganized or too depressed to be able to effectively advocate for themselves. Even when they are able to advocate, societal stigma, bias, and discrimination against individuals with mental illness may still limit the extent to which their voices are heard. For example, other people may not believe legitimate concerns voiced by an individual with mental illness, on the assumption that the illness is affecting the person’s judgment. These factors mean that individuals with mental illness are less likely to have social and political capital, and their needs and wishes are more likely to be ignored or unknown.

Psychiatrists are uniquely equipped to provide medical leadership beyond clinical issues toward larger societal issues pertaining to mental health. As physicians, we receive extensive training in the biology of the body and mind during medical school and then during residency gain deep expertise in the diagnosis of the full range of mental illnesses as well as their treatments, both psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic. Some of us undertake even more subspecialty training during fellowships prior to entering practice. We are critical to the functioning of the mental health care system and have a broad view of its workings. As physicians, our job title and medical expertise also give us a place of respect within society. For these reasons, we are ideally positioned to lead the way in advocacy for mental health.

Psychiatry is also arguably the most controversial specialty in the house of medicine, which only increases the need for advocacy in this field. Because the illnesses we treat are often “invisible” (both physically and in terms of diagnostic testing) and because they can profoundly alter the way individuals experience and are experienced by the world, they are imbued with a mystique that can quickly escalate to fear and judgment, especially during times of political turmoil. Across nations and across time, psychiatric labels and treatments have been particularly vulnerable to being used as tools of social control. Among medical diagnoses, mental illness diagnoses are especially prone to being influenced by changing societal attitudes about what is behaviorally “normal” or “abnormal.”

These factors contribute to a variable and at times hostile perception of psychiatry in modern popular culture. There is no “anti-pediatrics” or “anti-nephrology” movement, but there is an active and vocal anti-psychiatry movement. Chemotherapy, which has both lifesaving properties and potentially severe side effects, is not generally considered to be a barbaric and unnecessary treatment, but electroconvulsive therapy, which also has lifesaving properties and potentially severe side effects, sometimes is. Given the historical background and the current atmosphere surrounding psychiatry, our field urgently needs ethical, effective, and humanitarian advocates at its helm, both to promote the fair and equal treatment of individuals with mental illness and to guard against potential future injustices against our patients and our profession.

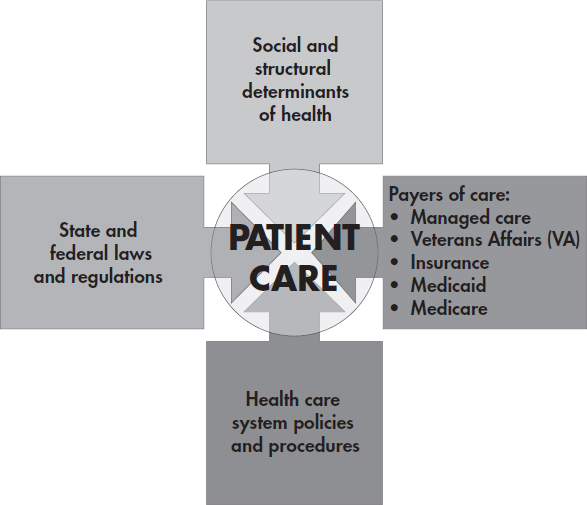

In addition, before the advent of the medical-industrial complex and today’s complicated health care systems, the quality of care that a patient experienced depended primarily on factors within the provider-patient dyad. Today, however, the provider and patient are no longer truly autonomous when they make mental health care decisions, and multiple factors now impact the type and quality of care that a patient receives. These include the payers who finance the care, the health care systems where the care is received, and the state and federal regulations that govern the care. Also, we now understand the powerful role that social and structural determinants of health play in contributing to health care outcomes, including mental health outcomes, and these must also be considered whenever we as physicians engage in advocacy. Given this complex interplay of factors influencing mental health care in the modern era (

Figure 1–1), psychiatrist-advocates are needed now more than ever to ensure high-quality, equitable care for our patients.

Finally, our mental health care system is in the process of undergoing enormous transformation. The decisions made in the next few years will impact the way health care is organized and delivered for generations to come. Understanding how to advocate for a better mental health care delivery system is critical to ensuring that patients have access to quality mental health care services.

All of these various considerations boil down to one point: we, as psychiatrists, must advocate for our patients. In some cases, such as when patients are incapacitated by symptomatic mental illness, we must advocate on behalf of our patients, by acting in their best interests when they have a diminished capacity for effective advocacy. In other cases, such as when they do have the agency to advocate for themselves but need a physician’s help to navigate the complexities of the health care system, we must advocate in support of our patients and lend our voices and our expertise to the causes they believe will have the greatest positive impact on their well-being. In still other cases, such as when patients and psychiatrists are both stakeholders who would be impacted by proposed legislative changes, our role is to advocate alongside our patients, joining with them in solidarity to ensure a health care system that will benefit both their care and our ability to deliver it. Our clinical work as psychiatrists already improves the mental health of patients—and our advocacy work as psychiatrists will improve the mental health of patients, populations, and nations.

Health Advocacy: Historical Context and Recent Trends

There is no single, unified history of health advocacy, in part because what we consider advocacy in this book and in these times has been, and still is, known by various names. That being said, the field of social medicine offers a useful example of an academic medical discipline that contains components of advocacy at its core (

Geiger 2017). German physician Rudolph Virchow (1821–1902), a foundational figure in social medicine, wrote, “Medicine is a social science, and politics nothing but medicine at a larger scale” (

Mackenbach 2009, p. 181). It has been argued that this oft-quoted statement is a summary of “public health’s biggest idea: human health and disease are the embodiment of the successes and failures of society as a whole, and the only way to improve health and reduce disease is by changing society by, therefore, political action” (

Mackenbach 2009, p. 181). In this spirit, social medicine looks beyond the health of individuals to the health of populations and holds that physician involvement in shaping what are known today as the social and structural determinants of health is necessary for healthy individuals, populations, and societies. This involvement can take place through public health efforts and, of course, through political and other forms of advocacy.

The history of medicine contains many examples of advocacy, at both the individual and the collective levels, by both physicians and nonphysicians. In the area of mental health, perhaps one of the best-known historical examples of advocacy is that of Dorothea Dix (1802–1887), whose vigorous and steadfast advocacy efforts on behalf of impoverished individuals with mental illness led to the opening of the first mental asylums in the United States. Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), the founder of modern nursing, also led multiple advocacy efforts that resulted in social reform, including for improved hospital sanitation and for increased acceptance of women in the workforce, especially as nurses. Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865), a Hungarian physician, advocated for the practice of handwashing prior to contact with obstetric patients in order to reduce infection; although he was ridiculed for this advice and died years before his practice was validated, we remember him today as a pioneer of germ theory who saved the lives of numerous mothers. Examples of more recent advocacy efforts in medicine, including by physicians, are the promotion of seat belt use in vehicles, the placement of health warning labels on cigarette packs, the removal of homosexuality as a DSM diagnosis, and health education campaigns about the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Many more examples of recent and current advocacy efforts by physicians, especially psychiatrists, ranging from the everyday advocacy associated with individual patient care to collective advocacy efforts for sweeping changes in health care, can be found throughout the pages of this book.

As these examples show, health advocacy can take many forms and span many health concerns. Furthermore, physician health advocates need not limit themselves to speaking out only about issues directly related to health care (e.g., cigarette smoking, seat belt use); there are precedents in which physicians have sought to, and succeeded in, advocating on larger societal issues that are likely to impact health (e.g., nuclear warfare, climate change). Finally, not all of the examples we discuss in this book feature what are universally considered to be forms of advocacy, but we argue here, and throughout this book, that they really are forms of advocacy. We believe that this more inclusive approach democratizes the idea of advocacy, encourages more engagement in advocacy, and allows previously unacknowledged ways of impacting meaningful change to be named and appreciated as the acts of courage and vision that they are.

Traditional medical training is not known for producing advocates. In fact, if we consider advocacy to be an act of enlarging our view beyond the problems of individual patients to the problems of populations and societies, traditional medical training does the exact opposite: it finely hones our ability to understand health and disease in individual patients, while largely ignoring how societal contributions influence those states of health and disease. One factor underlying this educational omission can be attributed to the need to prioritize basic competency in the care of individual patients, which, of course, is required in order to be a physician. Another factor may have to do with prevailing attitudes about the physician’s proper role in society.

There are those who assert that advocacy beyond the level of the individual patient falls outside of a physician’s professional concerns because “political advocacy is detached from the doctor-patient relationship” (

Huddle 2011, p. 380). However, this assertion is based on the underlying belief that there is such a thing as “pure” medicine untouched by the “toxins” of the social and political contexts in which that medicine is practiced—a belief we argue is both erroneous and detrimental to our patients and our profession because it allows sociopolitical interest groups, often financially motivated, to capitalize on our inaction. As the saying goes, “If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.” If we as psychiatrists, the physician leaders in mental health care, do not advocate for our patients, then who will? Silence on our part would mean putting our patients at risk for even greater disenfranchisement and discrimination. Psychiatrists must advocate to block actions, programs, and legislation that could potentially harm patients or worsen the systems in which patient care is embedded, as well as to advance those that serve our patients’ best interests and improve their health and well-being.

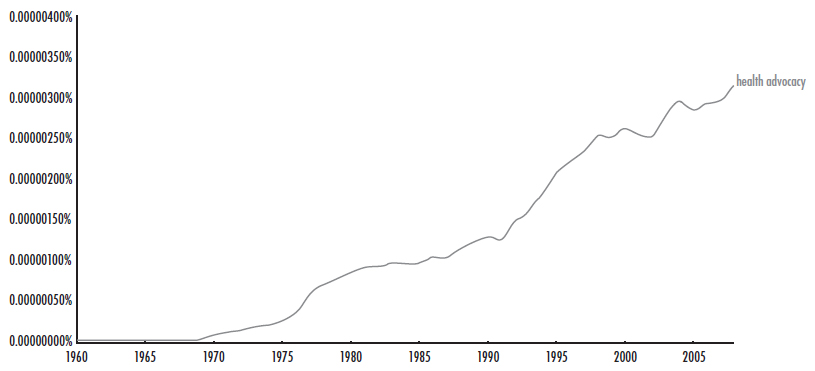

Fortunately, over the past several decades, the medical profession has come a long way in confronting the reality of the social and political factors that influence our patients’ health and the health care system. Interest in health advocacy among physicians and other health care professionals has increased substantially, in concert with rising concerns about the sustainability of the current health care environment and the efficiency, quality, and value of the health care that is currently delivered. As a rough demonstration of this burgeoning interest, entering the term “health advocacy” into Google Ngram Viewer (a search engine that charts the frequencies of words and phrases found in printed sources over time) shows a dramatic and continuing increase in the use of the term since the late 1960s (

Figure 1–2).

Advocacy as Professional Responsibility

Both professional societies and medical training organizations have increasingly acknowledged advocacy as a core professional responsibility among physicians. As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, in 2001, the AMA listed advocacy as a fundamental responsibility of physicians in its Declaration of Professional Responsibility (

American Medical Association 2001). Similarly, the medical training framework of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada includes the “health advocate” role as one of seven essential competencies to be addressed in medical education (

Frank et al. 2015).

Psychiatry has followed suit in this trend toward increased recognition and teaching of advocacy. In 2002, the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA’s) Board of Trustees officially endorsed the AMA’s Declaration of Professional Responsibility, including its clause on advocacy (

American Psychiatric Association 2002). In terms of advocacy teaching, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in psychiatry now considers “advocating for quality patient care and optimal patient care systems” to be a competency under the domain of “systems-based practice” (

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education 2019). The Psychiatry Milestone Project, a joint effort of the ACGME and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN), also mentions advocacy as a competency under multiple domains, including those of medical knowledge, systems-based practice, and professionalism (

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology 2015).

Still, compared with some other medical specialties, psychiatry has a less robust tradition of advocacy teaching and lags behind in terms of advocacy engagement and effectiveness (for more information, see

Chapter 8, “Education as Advocacy,” and

Chapter 11, “Advocacy for Children and Families”). Because psychiatry is a specialty with a high need for advocacy, encouraging a greater culture of advocacy among our fellow psychiatrists is of paramount importance if we are to effect broad and lasting changes for our patients and our profession. This attention to advocacy as one of our core professional responsibilities should begin in medical school, continue throughout residency and fellowship, and last over the entire course of a psychiatrist’s career. However, that is easier said than done because advocacy remains a “frontier” in medical education and practice. Achieving a strong and sustained culture of advocacy in the field of psychiatry will require a mass paradigm shift in the way we think about our professional responsibilities to our patients, our profession, and our society as a whole—which begins by clearly conceptualizing what advocacy is and defining its boundaries, norms, and best practices.

About This Book

It is our hope that this book will lay the foundation for how we can all embrace our role as psychiatrist-advocates, by providing both a theoretical understanding and a practical toolkit for mental health advocacy in its myriad forms. We firmly believe that there are many ways to advocate, and therefore we have devoted chapters to multiple types and levels of advocacy and to the specific advocacy concerns of particular populations. We further firmly believe that at all stages of our careers, we as psychiatrists can be effective advocates and that each generation of psychiatrists contributes its own unique and critical advocacy voice and vision. To reflect our conviction, we have invited psychiatrists from a wide variety of career stages to author chapters in this book, and the book contains guidance that is relevant to new and seasoned advocates alike, from medical students to late-career psychiatrists.

To this point in the chapter, we have defined

advocacy as it applies to health care; argued for the importance of advocacy, especially in psychiatry; and given historical and recent examples of health-related advocacy. In the rest of Part I, “Understanding Advocacy,” we address how to think about advocacy conceptually and outline general ethical principles to consider when engaging in advocacy (

Chapter 2); describe several seminal advocacy issues within psychiatry that impact both our patients and our profession, as well as ways we might tackle them (

Chapter 3); and provide an overview of the skills and knowledge needed to become an advocate (

Chapter 4).

We then shift from discussing the theoretical aspects of advocacy in psychiatry to discussing its practical aspects—that is, how to actually do the work of advocacy in multiple contexts. In Part II, “Practicing Advocacy,” we consider advocacy engagement at several of the different levels of advocacy (Chapters 5–7) as well as within several of the different types of advocacy (Chapters 8–10). Although we cannot exhaustively cover all of the possible levels and types of advocacy, we believe that the chapters in this part of the book provide a foundational introduction to some of the most common ones.

In Part III, “Advocacy for Special Populations,” we home in on the unique advocacy needs of certain special populations (Chapters 11–20). Again, this part of the book is not an exhaustive catalogue of all the patient populations that may have unique advocacy needs. However, it aims to be a starting point for conversations about how we can best advocate for these and other patients whose specific concerns and social and structural determinants of health must be taken into account both in clinical care and in advocacy.

Finally, Chapters 3, 4, 6, and 10 include short interviews with advocacy role models. These are real psychiatrist-advocates at different stages of their careers who come from a variety of backgrounds and have dedicated themselves to addressing different advocacy issues through various methods of advocacy. We hope that the advocacy success stories of these psychiatrists will inspire and motivate you and other current or budding psychiatrist-advocates who are reading this book to keep sharpening your advocacy skills and to stay confident that our efforts do make a difference.

All psychiatrists can be advocates, and more psychiatrists are becoming advocates every day. By sharing our experiences, encouraging each other, and fostering a culture of advocacy within our profession, we will become an organized, impassioned, and effective group of psychiatrist-advocates at the front lines of shaping the future of mental health care.