Books published by American Psychiatric Association Publishing represent the findings, conclusions, and views of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the policies and opinions of American Psychiatric Association Publishing or the American Psychiatric Association.

Names: Joshi, Shashank V., editor. | Martin, Andrés, editor. | American Psychiatric Association Publishing, Publisher.

Title: Thinking about prescribing : the psychology of psychopharmacology with diverse youth and families / edited by Shashank V. Joshi, Andrés Martin.

Description: First edition. | Washington, DC : American Psychiatric Association Publishing, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021040735 (print) | LCCN 2021040736 (ebook) | ISBN 9781615373888 (paperback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781615373895 (ebook)

Subjects: MESH: Mental Disorders—drug therapy | Child | Psychopharmacology—methods | Cultural Diversity

Classification: LCC RM315 (print) | LCC RM315 (ebook) | NLM WS 350.33 | DDC 615.7/8—dc23

A CIP record is available from the British Library.

CONTENTS

Contributors

Uncovered

Prescriber, Prescribe Thyself (By Way of Introduction)

Andrés Martin, M.D., M.P.H., and Shashank V. Joshi, M.D.

Part I: Principles

1 Think Again About Prescribing: The Psychology of Psychopharmacology

Kyle D. Pruett, M.D.

2 The Many Facets of Alliance: The Y-Model Applied to Child, Adolescent, and Young Adult Pharmacotherapy

Magdalena Romanowicz, M.D., Sarah Rosenbaum, M.D., M.P.H., and Carl Feinstein, M.D.

3 Psychodynamics of Medication Use in Youth With Serious Mental Illness

Barri Belnap, M.D., Erin Seery, M.D., John Azer, M.D., and David Mintz, M.D.

4 “What’s in It for Me?”: Adapting Evidence-Based Motivational Interviewing and Therapy Techniques to Adolescent Psychiatry

John J. DiLallo, M.D.

5 Providing Psychoeducation in Pharmacotherapy

Srinivasa B. Gokarakonda, M.D., M.P.H., and Peter S. Jensen, M.D.

Part II: Partners

6 #KeepItReal: The Myth of the “Med Check” and the Realities of the Time-Limited Pharmacotherapy Visit

Max S. Rosen, M.D., and Anne L. Glowinski, M.D., M.P.E.

7 Pharmacotherapy or Psychopharmacotherapy: When Therapist and Pharmacologist Are Different People—or the Same Person

Mari Kurahashi, M.D., M.P.H., Elizabeth Reichert, Ph.D., Nithya Mani, M.D., and David S. Hong, M.D.

8 The Pharmacotherapeutic Role of the Pediatrician, Advanced Practice Clinician, and Other Primary Care Providers

Katherine M. Ort, M.D., and Amy Heneghan, M.D.

Part III: Settings

9 The Pharmacotherapeutic Alliance in School Mental Health

Andrew Connor, D.O., and Shashank V. Joshi, M.D.

10 When Time Is Tight and Stakes Are High: Pharmacotherapy, Alliances, and the Inpatient Unit

Andrea Tabuenca, Ph.D., Jung Won Kim, M.D., and Shih Yee-Marie Tan Gipson, M.D.

11 Telepsychiatry Goes Viral: Psychotherapeutic Aspects of Prescribing Via Telemedicine Amid (and After) COVID-19

Jeff Q. Bostic, M.D., Ed.D., Sean Pustilnik, M.D., and David Kaye, M.D.

Part IV: Populations

12 Alliance Issues to Consider in Pharmacotherapy With Transition-Age Youth

Jennifer Derenne, M.D., Farrah Fang, M.D., and Anthony L. Rostain, M.D., M.A.

13 The Pharmacotherapeutic Alliance When Working With Diverse Youth and Families

Takesha Cooper, M.D., M.S., Michelle Tom, M.D., and Erin Fletcher, M.D., M.P.H.

14 The Psychopharmacotherapeutic Alliance When Resources Are Limited

Arthur Caye, M.D., Ph.D., Brandon A. Kohrt, M.D., Ph.D., and Christian Kieling, M.D., Ph.D.

Part V: Research

15 Building a Therapeutic Alliance in Psychopharmacology During Clinical Trials: Ethical and Practical Considerations

Manpreet K. Singh, M.D., M.S., and Janice Cho, M.D.

16 The Power of Placebo

Jeffrey R. Strawn, M.D., Jeffrey A. Mills, Ph.D., Tara S. Paris, Ph.D., and John T. Walkup, M.D.

Part VI: Becoming

17 The “Good Enough” Pediatric Psychopharmacotherapist: Practical Pointers in Six Parables

Ian Tofler, M.B.B.S.

18 Teaching and Mentoring the Next Generation of Pediatric Psychopharmacotherapists

Dorothy Stubbe, M.D., Isheeta Zalpuri, M.D., Mandeep Kaur Kapur, M.D., and Donald M. Hilty, M.D., M.B.A.

Gratitude

Shashank V. Joshi, M.D.

Index

CONTRIBUTORS

John Azer, M.D.

The Austen Riggs Center, Stockbridge, Massachuseutts

Barri Belnap, M.D.

The Austen Riggs Center, Stockbridge, Massachuseutts

Jeff Q. Bostic, M.D., Ed.D.

Department of Psychiatry, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, D.C.

Arthur Caye, M.D., Ph.D.

Division of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre; Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Janice Cho, M.D.

Resident Physician in Psychiatry, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California

Andrew Connor, D.O.

Ohana Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of Monterey Peninsula, Monterey, California

Takesha Cooper, M.D., M.S.

Program Director, Psychiatry Residency Training Program; Vice-Chair of Education; Equity Advisor; and Chair, Admissions Committee, Department of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, University of California, Riverside School of Medicine, Riverside, California

Jennifer Derenne, M.D.

Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford, California

John J. DiLallo, M.D.

Psychiatrist in Private Practice, Dobbs Ferry, New York

Farrah Fang, M.D.

Staff Psychiatrist, Stamps Health Services, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia

Carl Feinstein, M.D.

Clinical Professor and Vice Chair, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, University of California, Riverside School of Medicine, Riverside, California; Emeritus Professor of Psychotherapy, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California

Erin Fletcher, M.D., M.P.H.

PGY 3 Psychiatry Resident, Department of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, University of California, Riverside School of Medicine, Riverside, California

Shih Yee-Marie Tan Gipson, M.D.

Instructor, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Anne L. Glowinski, M.D., M.P.E.

Weill Institute for Neurosciences, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco, San Fransisco, California

Srinivasa B. Gokarakonda, M.D., M.P.H.

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas

Simone Hasselmo, A.B.

Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut

Amy Heneghan, M.D.

Pediatrician in Private Practice, Palo Alto, California

Donald M. Hilty, M.D., M.B.A.

Professor and Vice Chair of Veteran’s Affairs, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California Davis School of Medicine, Sacramento, California

David S. Hong, M.D.

Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California

Peter S. Jensen, M.D.

Board Chair, The REACH Institute, New York, New York; Adjunct Professor of Psychiatry, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas

Shashank V. Joshi, M.D.

Professor of Psychiatry, Pediatrics, and Education, Stanford University School of Medicine and Graduate School of Education; Director of Training in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Director of School Mental Health at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, Palo Alto, California

Mandeep Kaur Kapur, M.D.

Administrative Chief Fellow, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California

David Kaye, M.D.

Professor of Psychiatry and Vice Chair of Academic Affairs, Department of Psychiatry, Jacobs School of Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, University of Buffalo, Buffalo, New York

Christian Kieling, M.D., Ph.D.

Division of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre; Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Jung Won Kim, M.D.

Faculty, Department of Psychiatry, Boston Children’s Hospital, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

Brandon A. Kohrt, M.D., Ph.D.

Division of Global Mental Health, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, George Washington University, Washington, D.C.

Mari Kurahashi, M.D., M.P.H.

Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California

Nithya Mani, M.D.

Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California

Andrés Martin, M.D., M.P.H.

Riva Ariella Ritvo Professor, Child Study Center, Yale School of Medicine; Medical Director, Children's Psychiatric Inpatient Service, Yale New Haven Health, New Haven, Connecticut

Jeffrey A. Mills, Ph.D.

Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, Lindner College of Business, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio

David Mintz, M.D.

The Austen Riggs Center, Stockbridge, Massachuseutts

Katherine M. Ort, M.D.

Clinical Assistant Professor, Departments of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Pediatrics, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, NYU Langone Health, New York, New York

Tara S. Paris, Ph.D.

UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, Los Angeles, California

Kyle Pruett, M.D.

Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Yale Child Study Center, Northampton, Massachusetts

Sean Pustilnik, M.D.

Department of Psychiatry, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, D.C.

Elizabeth Reichert, Ph.D.

Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California

Magdalena Romanowicz, M.D.

Program Director of Child and Adolescent Fellowship Training, Mayo School of Graduate Medical Education, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester, Minnesota

Max S. Rosen, M.D.

Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri

Sarah Rosenbaum, M.D., M.P.H.

Clinical Instructor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California

Anthony L. Rostain, M.D., M.A.

Chair, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Cooper University Health Care; Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, New Jersey

Erin Seery, M.D.

Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina

Manpreet K. Singh, M.D., M.S.

Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, and Director of the Stanford Pediatric Mood Disorders Program and the Pediatric Emotion and Resilience Lab, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California

Jeffrey R. Strawn, M.D.

Professor of Psychiatry, Pediatrics, and Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati, College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio

Dorothy Stubbe, M.D.

Associate Professor and Program Director, Child Study Center, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut

Andrea Tabuenca, Ph.D.

Clinical Assistant Professor, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California

Ian Tofler, M.B.B.S.

Kaiser West Los Angeles; Visiting Faculty, Department of Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, UCLA, Los Angeles, California

Michelle Tom, M.D.

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Fellow, Department of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, University of California, Riverside School of Medicine, Riverside, California

John T. Walkup, M.D.

Margaret C. Osterman Professor of Psychiatry, Pritzker Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital, Chicago, Illinois

Isheeta Zalpuri, M.D.

Clinical Associate Professor and Associate Program Director, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California

DISCLOSURE OF COMPETING INTERESTS

The following contributors to this book have indicated a financial interest in or other affiliation with a commercial supporter, a manufacturer of a commercial product, a provider of a commercial service, a nongovernmental organization, and/or a government agency, as listed below:

Peter S. Jensen, M.D.—Book publishing royalties: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; Guilford Press, Ballantine Books

Jeffrey A. Mills, Ph.D.—Support: Yung Family Foundation.

Tara S. Paris, Ph.D.—Research support: National Institute of Mental Health; TLC Foundation for Body-Focused Repetitive Behavior; Royalties: Oxford University Press.

Elizabeth Reichert, Ph.D.—Advisory board: Little Otter

Manpreet K. Singh, M.D., M.S.—Research support: Stanford Maternal Child Health Research Institute and Department of Psychiatry; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Aging; Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute; Johnson & Johnson; Allergan; Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; Advisory board: Sunovion; Consultant: Limbix; Past consultant: X, Moonshot Factory, Alphabet LLC; Book publishing royalties: American Psychiatric Association Publishing

Jeffrey R. Strawn, M.D.—Research support: Allergan, National Institutes of Health (NIMH/NIEHS/NICHD), Neuronetics, Otsuka; Yung Family Foundation. Material support and provision of consultation: Myriad Genetics; Book publishing royalties: Springer (two texts); Author: UpToDate; Associate Editor: Current Psychiatry.

John T. Walkup, M.D.—Royalties: Guilford Press and Oxford University Press (for multiauthor books published about Tourette’s syndrome); Wolters Kluwer (for CME activity on childhood anxiety). Unpaid advisor: Anxiety Disorders Association of America, Trichotillomania Learning Center; Board director: Tourette Association of America; Paid speaker: American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, American Psychiatric Association.

The following contributors have indicated that they have no financial interests or other affiliations that represent or could appear to represent a competing interferes with their contributions to this book:

Jeff Q. Bostic, M.D., Ed.D.

Janice Cho, M.D.

Takesha Cooper, M.D., M.S.

Jennifer Derenne, M.D.

Farrah Fang, M.D.

Carl Feinstein, M.D.

Erin Fletcher, M.D., M.P.H.

Srinivasa B. Gokarakonda, M.D., M.P.H.

Simone Hasselmo, A.B.

Shashank V. Joshi, M.D.

Nithya Mani, M.D.

Andrés Martin, M.D., M.P.H.

Magdalena Romanowicz, M.D.

Sarah Rosenbaum, M.D., M.P.H.

Michelle Tom, M.D.

PRESCRIBER, PRESCRIBE THYSELF

By Way of Introduction

It may seem unbecoming to open a book on children’s mental health on a surgical note. But there are at least two good reasons to do so. First, there is the answer to that old chestnut “Why did some of us become psychiatrists?” Because surgery wasn’t invasive enough. Surgery simply did not go sufficiently deep for some of our sensibilities. Second, and to learn from our colleagues in surgery and not just use them as strawmen for a tired quip, let’s give them this: Surgeons don’t for a second forget that scalpels are instruments, base metals at that. If only we psychiatrists had a similar mindset when prescribing our own pills. Alas, we forget all too often that our potions are partly instruments, base salts at times.

This volume is an invitation—an entreaty—to make good on the fact that our remedies are only as good as the way in which we dispense them, that prescribing psychotropic medications to developing children is as much the cold facts of molecules as it is the warm way in which we envelop them for delivery. It is a reminder that no matter how accurate said delivery may be, it all goes to naught—molecules be damned—if there is no one on the receiving end; a psychotropic not taken is perfectly inert and useless. But our goal should not end at mere “compliance” (an unfortunate term that reeks of power dynamics and hierarchical paternalism); ingesting a pill and letting its molecules fulfill their job description is but the start of a therapeutic process.

Simple conceptualizations of depression as a low serotonin condition or of stimulants as dopamine enhancers are as incomplete today as they are misguided. A chemical’s docking, Apollo-like, onto a receptor’s site to right a neurotransmitter’s tenuous balance is as romantic a throwback as a 1960s moon shot. Advances in molecular psychiatry over recent decades have made it clear that psychotropics are more than simple “keys” to neurotransmitter “locks.” The contact of molecule and receptor may be a start, but it is the secondary, tertiary, and subsequent messengers where the action truly lies. It is these elusive messengers that get in deep, that get closer to the actual machinery of the cell, that get the job done.

In a similar way, we should be not mere prescribers, the holders of key rings on our proverbial tool belts. We are—or should be, or aspire to be, or reclaim being—pharmacotherapists. Our own job description gets started well before molecules reach their targets; we are cognizant that the moment of chemical bonding is but another start; we remain humble in our commitment, recognizing that to deliver on the full potential of our treatment, we, too, must become and remain secondary, tertiary, and subsequent messenger systems. In his paraphrasing of Donald Winnicott in the book’s opening chapter, Kyle Pruett reminds us that “there is no such thing as just a prescription.” The prescription, the prescriber, and the prescribed are inherently intertwined; we ignore such bondings (chemical or otherwise) at our own therapeutic detriment.

Entering the Time Frame Continuum

By focusing too narrowly on the dosing of milligrams or the number and class of psychotropic medications, we can easily come to forget that time is that other key aspect of our posology. Time is perhaps our most valuable resource, and we would all do well to remember, after Cayer, Kohrt, and Kieling’s math (14), that “in psychiatry’s measure of time, more is more.” For example, in contemplating a patient who does not get better in the way or at the speed that we would hope for, we are comfortable—arguably too comfortable—increasing the milligrams or the number of psychotropics prescribed, and often both at the same time. We can capitulate in a similar fashion when facing some of the many outside influences that can intrude into the confines of our therapeutic relationship: unrealistic expectations for quick fixes or perverse incentives for “biological” treatments, as well as the pervasive influence of the pharmaceutical industry and the tentacular reach of its oversized advertising budget.

This volume is an invitation—an entreaty—to resist being pushed to, yielding to, or (banish the thought) opting for the circumscribed role of “medication prescriber.” Our first and best defense against such a misguided interpretation of our role is to remember the centrality of time within and across clinical encounters, to reclaim the dosing of ourselves, of the number and frequency of our visits, of our presence and therapeutic engagement within them. If these words seem too idealistic and removed from the daily realities of a child psychiatrist, contributions in this volume may help move clinicians away from “the myth of the ‘med check’ ” into the reality of the pharmacotherapy visit (6) to bridge the divide between what may be aspirational for some and what is possible for many. Milligrams dispensed are easy; time well spent is hard.

In pediatric psychopharmacology, establishing an appropriate frame is the yang to the yin of its time management. Pruett (1) again provides the pithy prescription for the task: “How you

are with your patient is as important as what you

do with your patient.” Three very different yet complementary chapters in this edited collection help establish a robust frame through which to be with our patients. Romanowicz, Rosenbaum, and Feinstein (2) have adapted to pharmacotherapy with children and adolescents the “Y-model” first posited by

Plakun and colleagues (2009), in which the therapeutic alliance, as the “stem of the Y,” provides a common point of entry for any clinical approach. In its original description, that stem bifurcates into psychodynamic and behavioral arms. Belnap, Seery, Azer, and Mintz apply psychodynamic principles to the context of pediatric psychopharmacology in their

chapter (3), a task that DiLallo takes on for cognitive-behavioral and motivational interviewing approaches in his (4). As appealing as such a neat tripartite model may sound, it only begins to tell the story when working with children and their families. The “stem” may instead be construed as more akin to a tree trunk and the two arms as but two of the many branches in a complex canopy. Indeed, a multitude of synergistic approaches is what we are routinely called on to muster as pharmacotherapists.

There is an additional and more recent connotation to the “frame” under discussion. And that is the virtual frame through which more of our visits are taking place these days. What started as telepsychiatry in the 1990s, designed to reach remote and particularly underserved locations, has rapidly evolved and made major inroads into routine pediatric psychopharmacology. The COVID-19 pandemic that started in March 2020 did in just a few months for the uptake of “virtual frames” what two decades of telepsychiatry educational efforts could not. Bostic and Kaye (11) have been pioneers and early settlers of these erstwhile barren virtual lands. They are also effective guides, enriching our vocabulary with terms such as tele-alliance, protection of the virtual space, telerapport, Freudian blips, screen empathy, and webside manner. What once was “treatment not as usual” has by now become second nature. We should not envision a future devoid of physical visits but rather embrace this new and complementary way of hitting the clinical target as but an additional arrow in our therapeutic quiver. As we embrace e-prescribing over paper scripts (remember those?), and as we swoon over the powers of the pixel, we should not lose sight of the fact that many areas of the world do not have e-prescription capabilities (14), or that families within even high-income nations like ours do not have access to adequate bandwidth or face inequities and barriers to care, including those entrenched through structural racism (13).

At Least Three (Though It Can Still Take Two to Tango)

Pharmacotherapy with adults is largely a dyadic affair between a patient and a prescribing clinician, an approach that at times works in the pediatric realm, particularly with adolescents and transition-age youth (12). However, the vast majority of time, prescribing psychotropic medications to children and adolescents involves other stakeholders—at times several of them—each with competing priorities or agendas to boot. For starters, given the enduring shortage of child psychiatrists, prescriptions often come from partners in a multidisciplinary team, including pediatricians or advanced practice registered nurses (8). In another common approach, treatment may be complemented and synergized among prescribing and nonprescribing clinicians (“split treatment,” the commonly used term for this arrangement, is another unfortunate misnomer because it emphasizes the potential divide rather than the intended cohesion) (7). The potential for cooperation and for different vantage points on children, including on their interactions with other children, is multiplied in schools or in congregate care settings such as inpatient units and residential facilities. Two chapters in this collection address the unique challenges and opportunities for pediatric pharmacotherapists working in schools (9) or inpatient environments (10).

In navigating what can be such tricky shoals, we’d all do well to heed the aphoristic advice by Gokarakonda and Jensen in their

chapter (5) that “the messenger may be ‘wrong’ even if the message is ‘right.’” To be the best possible messengers and to maximize the odds of our thoughtfully selected treatments to be consumed, Gokarakonda and Jensen go on to emphasize the role of psychoeducation and cooperation as part of a partnership with common goals. This partnership, when working with children and adolescents, most commonly involves parent(s) or legal guardians. Establishing a caring and trusting relationship with them can be as critical to the success and longevity of our treatment as making the youngster feel at ease with us—and with our psychotropic stand-ins, which we ask them to faithfully ingest.

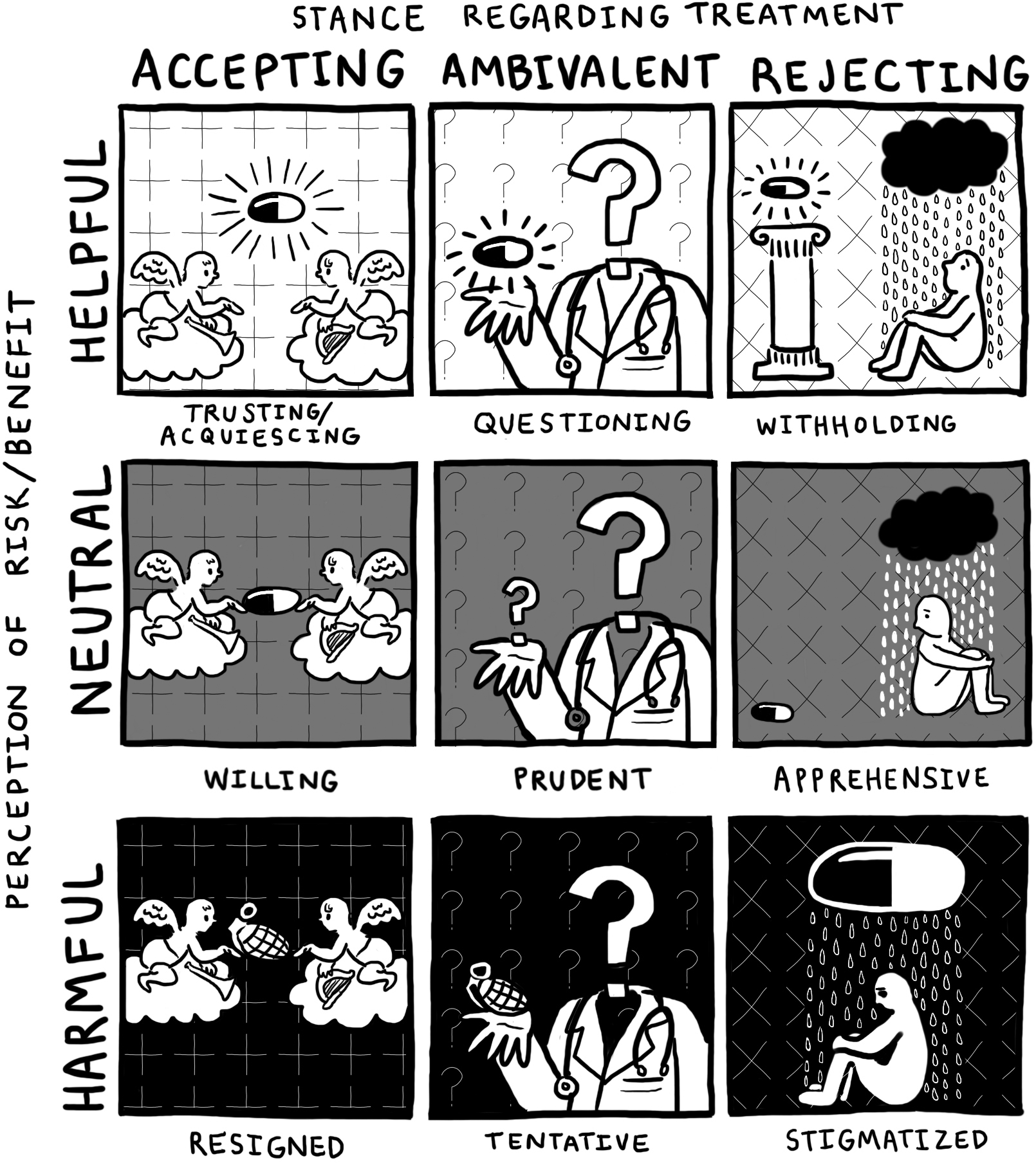

The richness of our work is in no small measure a reflection of the wide array of ethnoculturally diverse individuals and families we get to work with on a daily basis. And even as we respect their uniquely defining characteristics, we have found it helpful to approach clinical encounters—especially those involving the initial prescription of a psychotropic—through a framework that incorporates the perceived utility of the treatment on the one hand and the stance regarding treatment on the other. We depict the intersection of these two axes in the figure below and go on to provide examples from our clinical practice that exemplify some of the cells in the resulting matrix.

Stance Regarding Treatment

In an optimal situation, if an admittedly idealized one, a child has no preconceived notions about the potential utility of a medication: It is neither helpful nor harmful; it just is. By contrast, when the stance regarding treatment is not entirely neutral but rather ambivalent because ingesting a foreign substance is, if nothing else, a change, at least a modicum of questioning serves a role toward self-preservation. We think of this central cell as prudent, one in which a parent (or a child, or the two combined) wants to know more in order to make a well-informed decision. The underlying but often unspoken request may be as simple as this: Help me gain trust (in you, in the pill, in whoever you are and whatever this is).

Our hand should tremble (just a bit) before we write a prescription for a young child; a parent should tremble (just a tad more) before first dispensing the medication. The upper-left corner of our proposed matrix is not without its challenges. For starters, there is a fine line between trusting and acquiescing, and children or parents can be too willing to agree to a treatment without “reading the fine print” first. A lack of tremors on either side suggests the possibility of idealization at best, of recklessness at worst.

Children and parents rarely come to us as blank slates, devoid of memory or expectation, or without fears and desires. We face the willing when the prescriber is perceived in a better light than the prescription. When faith in a potion prevails over that in its prescriber, the questioning may stick around to accept a trial: not the medication trial so much as our own. The tentative may be willing to tolerate psychotropics deemed potentially risky or harmful as long as they can have enough of our trust to go on. We meet the apprehensive when it is we who are the ones in question while a psychotropic is given an opportunity to prove its worth.

Moving from any of these contiguous quadrants toward the elusive top-left corner of the matrix—the one in which a predominantly helpful mediation is embraced within an informed and connected treatment relationship—can be as challenging as it is rewarding and conducive to good outcomes. Toward that end, the words we choose in pediatric pharmacotherapy are every bit as critical as the milligrams we dispense. As psychiatrists, we cherish words, though at times we overuse them. Prime examples of such verbal prolixity include the explanation of arcane and outdated mechanisms of action, an emphasis on encyclopedic side effect lists, and a penchant for the legalese of informed consent. To make matters worse, these words have a way of morphing into reams of electronic boilerplate content.

Surely there is a way to reclaim the healing power of pithier wordsmithing. And there is. First, go for the object. And the object in this instance is not the medication (it’s the child, stupid!). Second, when addressing how treatments work, realize that “chemical imbalance” and the neurotransmitter hi-lo index are more helpful in binding our own anxieties than those of our patients. Accept the fact that we don’t really know how our medicines work and step off the podium already. When talking to kids, call the things “medicines” while you’re at it, not “medications” or (the horror!) “psychotropics.” A “pill” can be “candy,” and children do well to take neither one from a stranger. By contrast, a “medicine” is a known entity, and one that generally helps kids feel better.

When addressing side effects, beware of unleashing terms such as “sudden death” and “suicide risk”; these horses are hard to put back in their barns. Not that you should elide them completely; follow instead your own advice to “start low and go slow.” Start in fact at the lowest, a truism that often goes unsaid: the most common side effect is no side effect. And build up from there: there are the relatively common side effects that tend to be minor and well tolerated, and there are the more infrequent and serious ones. Address the ones that are more likely to be pertinent, and remember that some things can’t be unheard. After a few minutes, only the most salient words are likely to be heard. You don’t have to build Rome in a day—or, by frightening your audience away, demolish it in a day either. Obtain informed consent but stop from making patients and their families feel part of an informed coercion process. And finally, did we mention going for the object? It is right there, staring you in the face. So stop yapping already.

Placebo, Nocebo, No Dice

The placebo effect gets a bad rap, what with all of its muddying of the clinical trials we base so much of our evidence base on (15 and 16). But the placebo effect deserves a closer look as more than methodological noise. The nonpharmacological powers vested in a medication, and the positive meaning and healing expectations attributed to it, can be powerful allies in leading to positive change. By contrast, placebo’s younger cousin, the nocebo effect, can be a force to reckon with because it can taint with its negative messaging, dashed hopes, and harmful attributions. When expectations are not only the patient’s but those of their parents or guardians, of their schoolteachers or coaches, as well as of their social-media-frenzied feeds, we need to pause to consider the interlocking effects of what

Grelotti and Kaptchuk (2011) initially conceptualized for adults, and

Czerniak et al. (2020) later refined for children and adolescents, as the

placebo by proxy or the

nocebo by proxy effects. We may think of our consulting rooms as a confidential sanctum of privacy, but conversations about treatment rarely end at our doorstep; they are more likely to only get started there, and we risk enlarging our blind spots if we sidestep this chorus of informative or inflammatory influences.

The impact of the placebo (and of the placebo by proxy) is highest in the top row of our proposed matrix. How can we approach its right-most cell, withholding, in which a treatment perceived as mostly beneficial is rejected? A self-defeating adolescent in the throes of depression may resist a medication she considers herself unworthy of taking or that may threaten to alter distorted views deemed by then integral to her personality. Gentle yet goal-directed motivational interviewing may permit us to close the gap and “get to yes.” A parent or guardian may resist giving a psychotropic out of an understandable abundance of caution, but there are times when untoward hesitation or repeated instances of abandoned treatment may require the involvement of child protective services. No one can force a child to take a medication, and the instance of involuntary administration (as in the case of an intramuscular injection) should remain a (very) last-resort measure within an emergency department or inpatient setting (10). Long-acting depot antipsychotics don’t have a safety record in minors to warrant their regular use. In short, protective services, the courts, and injectable medications do have a role in contemporary psychiatry. But they are rarely invoked or useful beyond an acute emergency situation in the case of pediatric pharmacotherapy.

By contrast, the impact of the nocebo (and the nocebo by proxy) is most relevant in the bottom row of the matrix. Resigned patients and families may be accepting of treatment that they perceive as potentially hazardous. For many of these all too common scenarios, we provide concrete suggestions we have found helpful in our own practice.

First, it is often our oversharing of details—in the spirit of being transparent and comprehensive—that can corner us into this resigned quadrant. We do not advocate for the outright omission of side effect discussions, but do make a case for being less meticulous and defensive. Take as an example suicide risk in the context of starting an antidepressant. Time and again we hear necessary and well-meaning conversations about the relative risk of emergent suicidal ideation among children taking antidepressants compared with those who are unexposed. So far so good. But what we all too rarely hear is the more relevant comparison—that of higher rates of death by suicide among the untreated. Our cathartic confessionals scare away more often than they meaningfully engage patients and their families: we should resist clinching defeat (in the form of losing a patient to follow up, or tragically, to suicide) out of the jaws of victory (in the form of starting a potentially life-saving medication embedded within a therapeutic relationship).

Second, and relevant to all cells in the matrix, is a reminder that our task is in no small measure one of shared meaning-making. Romanowicz et al. (2) are direct and aphoristic in their advice: “The parent and patient most often seek consultation to receive help with the patient’s symptoms, not to receive a DSM diagnosis. Help them co-create meaning and make sense of their symptoms.” In an important article, David

Mintz (2019, p. 237) expands this notion, alerting us to attend to the meaning of medication, particularly given that “[w]hile all people who take medications may attach pathogenic meanings to them, children and adolescents may be particularly vulnerable, because such effects can be amplified when incorporated into unfolding developmental processes.” Moreover, “when harm occurs at the level of meaning, the problem will be most usefully addressed at the level of meaning. Far too often, however, medicated children receive little or no psychological treatment.”

A Bitter Pill to Swallow: Stigma

In a sad parallel, the cell relegated to the very end of our conceptual matrix is the stigmatized confluence of treatment resisted on the basis of perceived harm. Or so we may be told. In fact, side effects (for example) may be the manifest excuse to turn down treatment, when closer listening may reveal that it is the stigma of mental illness that is the more relevant latent message. To take (or to give) a medication may be seen as tacit endorsement of an unwelcome diagnosis, of “otherness,” of frailty or fallibility we would rather ignore. As if the stigma of mental illness was not bad enough, the stigma on psychotropics can increase feelings of exclusion and isolation, of being “broken” and in need of “repair.”

There is much that we can do in our daily fight against the stigma of mental illnesses and the medications we often rely on to treat them. Psychoeducation is certainly prominent on the to-do list (5). But there is something else worth considering. It will sound radical, provocative, or boundary-breaking to some, and we respect those views. But for some others, being a bit radical, a tad provocative, a pinch boundary-breaking, and a whole lot legitimate and human, can be game-changing. Specifically, we have used as a tool for good the careful, selective sharing of our own diagnoses, treatments, medicines, family struggles, and recoveries. Whenever we have done this with the patient’s wellbeing in mind, when the sharing has been genuine and caring, when we have met with patients and their families in full shared humanity, at those moments, we have been pediatric pharmacotherapists, physicians, and humans at our very best. We are not alone in this endeavor, and we embrace the words of the courageous and pathbreaking Stephen

Hinshaw (2017, p. 250) in his sage insight that “fostering humanization may be the single most important weapon in the fight against stigma for . . . [m]ental disorders don’t afflict

them—a deviant group of flawed, irrational individuals—but

us: our parents, sons and daughters, colleagues and associates, even ourselves.” In short, we have nothing to disclose, but we have much to share.

In Closing—and in Dual Dedication

There is much that this volume will demand of its readers. Our intention is to inform and educate so as to elevate our practice rather than to raise expectations that may make us feel inadequate. To the contrary, the penultimate chapter addresses a serious matter in a lighter note; it is, after all is said and done, more than sufficient to be “good enough” pharmacotherapists. By reading these words, you are already proving your good enough–ness. Our aim and our hope is to take you to a place of “good enough +1.” That is the goal that as educators of the next generation of practitioners we have dedicated our professional lives to fulfilling (18).

As we look to a future generation—of newer psychotropic agents one day, of children with lessened burdens well before that, and of trainees emerging as inspiring colleagues and friends each and every year—we must thank the generation that preceded and nurtured us. They are conceptually bilingual exemplars, with fluency in both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy: they embody the principles of psychopharmacotherapy we are hoping to instill in a new generation. Our hope is for this volume to serve as a salve against clinical monolingualism.

This project was first inspired by conversations with two beloved mentors, one in each coast. The chats that Andrés first had in the East Coast in the early aughts led to a chapter in which he was the understudy to Kyle Pruett’s visionary thinking and writing (

Pruett and Martin 2003). As our thinking evolved, we widened the learning circle, with Shashank joining as a fellow contributor (

Pruett et al. 2011). In the West Coast, Shashank learned from, and emulated, another towering figure, Carl Feinstein. Their conversations were not only influential; they were also career-determining and went on to inform an entire new line of thinking and writing (

Joshi 2006). The two of us have been blessed by knowing and learning from these two special mentors and friends. They are far from the only mentors we have been fortunate to have, and we cherish the lessons from so many other colleagues, several of whom have contributed to this collective effort.

In their chapter in this volume (2), Carl and his coauthors riff off another giant:

As Leston

Havens (2004) said, “The first goal is for the clinician to find the patient, and the patient to find the clinician.” We have shown . . . it is not an easy process. Sometimes the clinician gets lost; sometimes the patient is difficult to find.

We concur and can add that finding mentors and inspiring teachers is not easy, either. We are grateful for having found this dynamic duo and learned from the best. We lovingly dedicate this book to them.

This volume is an invitation—an entreaty—to follow in their lead, to be our best professional selves and to do so in order to ease the suffering of the children and families we are privileged to serve. Kyle and Carl have given it their all throughout their careers. We emulate their example each day and invite you to do as well. In short, we invite you, dear fellow prescriber, to prescribe thyself.

Andrés Martin, M.D., M.P.H.

Shashank V. Joshi, M.D.

Illustrations by Simone Hasselmo, A.B.

References

Czerniak E, Oberlander TF, Weimer K, et al: “Placebo by proxy” and “nocebo by proxy” in children: a review of parents’ role in treatment outcomes. Front Psychiatry 11(March):169, 2020 32218746

Grelotti DJ, Kaptchuk TJ: Placebo by proxy. BMJ 343:d4345, 2011 21835868

Havens L: The best kept secret: how to form an effective alliance. Harv Rev Psychiatry 12(1):56–62, 2004 14965855

Hinshaw SP: Another Kind of Madness: A Journey Through the Stigma and Hope of Mental Illness. New York, St. Martin’s Press, 2017

Joshi SV: Teamwork: the therapeutic alliance in pediatric pharmacotherapy. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 15(1):239–262, 2006 16321733

Mintz D: Recovery from childhood psychiatric treatment: addressing the meaning of medications. Psychodyn Psychiatry 47(3):235–256, 2019 31448987

Plakun EM, Sudak DM, Goldberg D: The Y model: an integrated, evidence-based approach to teaching psychotherapy competencies. J Psychiatr Pract 15(1):5–11, 2009 19182560

Pruett K, Martin A: The psychology of psychopharmacology: thinking about prescribing, in Pediatric Psychopharmacology: Principles and Practice. Edited by Martin A, Scahill LS, Charney D, Leckman JF. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003, pp 417–425

Pruett K, Joshi S, Martin A: The psychology of psychopharmacology: thinking about prescribing, in Pediatric Psychopharmacology: Principles and Practice, 2nd Edition. Edited by Martin A, Scahill LS, Kratochvil C. New York, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp 422–433