Advance Praise for Race and Excellence: My Dialogue With Chester Pierce

“At once deeply intimate and broad in scope, Ezra Griffith’s project to capture the life and accomplishments of Chester Pierce shares profound personal reflections on life, race, psychiatry, and beyond by both men. Nearly 25 years after its first publication, Race and Excellence remains a sensitive, insightful, and impactful contribution to understandings of race, privilege, and profession at this pivotal time of psychiatry’s—and society’s—reckoning with dismantling structures and institutions of racism. The life and lessons of Dr. Pierce shared through the lens of his accomplishments and choices about where to focus his extraordinary talents and energy challenge us all to be both deliberate and aspirational in our lives, work, relationships, and commitments.”

Rebecca Weintraub Brendel, M.D., J.D., DFAPA, President-Elect, American Psychiatric Association

“In Race and Excellence: My Dialogue With Chester Pierce, Ezra Griffith deftly combines elements of biography and autobiography to present us with a picture of the complex man that was Chester Pierce. Most readers may know that Pierce was a famous Black psychiatrist, but it is likely that few are aware of the breadth and depth of his unique personal and professional experiences. Here we learn about many of Pierce’s singular accomplishments, including being the first Black player on a segregated college football field south of the Mason-Dixon line, the first Black psychiatrist to become director and president of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, and the founding president of the Black Psychiatrists of America. In response to probing from Griffith that is both gentle and persistent, Pierce discusses everything from his important research on extreme environments such as Antarctica to his consultation with the creators of Sesame Street to his observations about the microaggressions endured day in and day out by Blacks and other minorities. In the process of their conversations, Griffith uncovers not just facts about Pierce’s life but also subtleties in his personality and strategies that helped him either avoid or overcome obstacles to his success. This well-written book would certainly be valuable even if it only documented the trailblazing life of Chester Pierce. I believe it is even more important, however, for what it reveals about how one might rise above an environment of tension and conflict to create a life of excellence and achievement.”

Larry R. Faulkner, M.D., President and CEO, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology

“In his biography of African American Harvard psychiatrist Chester Pierce, Ezra Griffith, a gifted storyteller and psychiatrist, provides the reader a window into the life of a great man at close psychological range. Born in 1927, Pierce was influenced by the quiet support of his mother and the entrepreneurial determination of his father, once a shoe shiner in Harlem. By age 25, he had graduated from Harvard Medical School. Pierce was an intellectual with wide-ranging scholarship and professional achievements, including consultancy to Sesame Street and NASA. However, he was not immune to the racial affronts ever present in the United States. Such encounters highlighted the fabric of racial prejudice—the microtraumas and macrotraumas—against Blacks. He cofounded the professional association Black Psychiatrists of America as a pathway for positive impact. Griffith writes, “I never wanted just to tell Chet’s story; I wanted to work his story out, to measure it, to try it on, to figure out which parts are good for me and for other blacks so earnestly seeking heroes.” Griffith most certainly achieves this goal. Race and Excellence is as contemporary in its relevance today as it was when first issued in 1998.”

Shoba Sreenivasan, Ph.D., Adjunct Professor, Keck USC School of Medicine, Institute of Psychiatry, Law and Behavioral Sciences; Forensic Psychologist—Forensic Services Division, California Department of State Hospitals

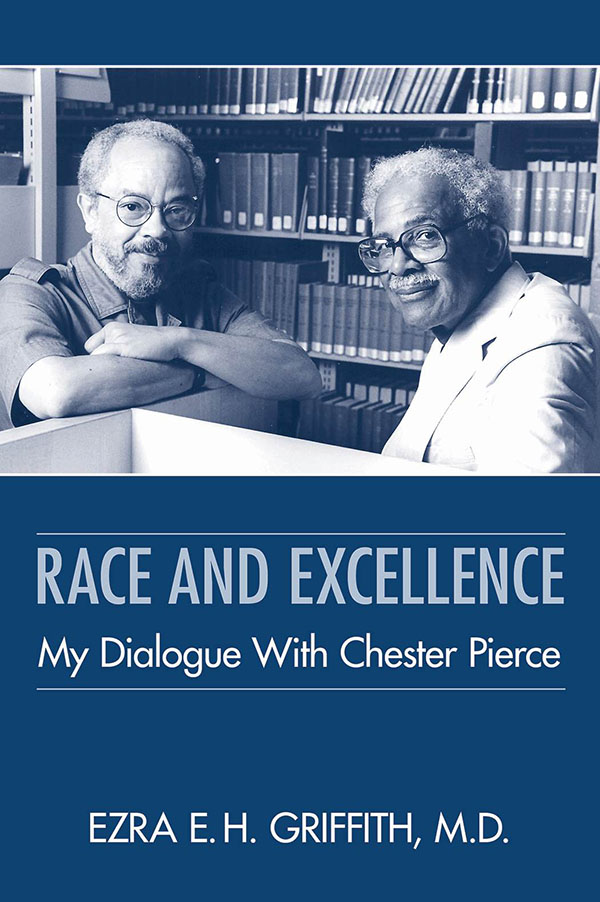

EZRA E.H. GRIFFITH, M.D.

Books published by American Psychiatric Association Publishing represent the findings, conclusions, and views of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the policies and opinions of American Psychiatric Association Publishing or the American Psychiatric Association.

Reprint edition with bonus material; University of Iowa Press edition published 1998

A CIP record is available from the Library of Congress.

A CIP record is available from the British Library.

Preface

Over the past two decades, I have been a serious student of the Black life. I have been unceasingly curious about how African American men and women tell the stories of their lives, recount their successes and failures, explain their way of coping with everyday trauma, and joyously announce their celebrations. Such storytelling has held special fascination for me because I have viewed it as a window on thinking and problem-solving by African Americans. Specialists from other disciplines have been quick to see the literary, historical, and cultural significance of the Black life story. But the psychological insights offered in those texts also have very special value, especially because the stories are from men and women who come from varied socioeconomic, historical, educational, religious, color, and work backgrounds.

The personal story is a helpful document about life at a given time because it tends to put flesh on the bones of a historical period that may be captured only incompletely by statistics and other summary data. What slave narrators, for example, say about their lives as slaves is worth hearing, even if their narratives evoke more questions about the inner lives of slaves than the stories ultimately answer. But think what our contemplations about slavery would be like if they were not informed by the personal ruminations of slaves themselves.

Still, recounting a life history isn’t free of complexity. The autobiography, for example, cannot be expected to escape the critical analysis given to other art forms. That is why the careful reader wants to know the reason for the author’s decision to tell his story: whether the author is seeking to set the record straight about some particular set of facts, whether the author’s recall is being subjected to psychological or other duress, what the author may be deliberately or unconsciously including or excluding. In reading the personal stories of others, we should not be expected to suspend all our critical faculties.

I have always wanted to know what Malcolm X believed was his own version of the truth, even if I would then have trouble accepting it. By any measure, Malcolm was one of the important Black leaders of this country’s Civil Rights movement in the 1960s and a major figure in one of the new African American religious movements of the twentieth century. The autobiographical explication of his relationship with his mentor, Elijah Muhammad, like the description of his parents and his early love of White women, had to be made by him. Even if, under later scrutiny by readers, the story would seem to spring holes, it still serves as Malcolm’s version and no one else’s. It is Malcolm’s reality, which deserves serious consideration no matter what one’s standards are for determining historical or psychological truth. But I still have questions about his story and would continue to have them even if the story had been related by a historian, anthropologist, sociologist, or other professional. It is obvious and accepted that even apparently objective professionals can be found guilty of grinding some distinctly personal axe. So storytelling is not without its problems.

One can hardly forget Erik Erikson’s brilliant reminder, articulated in Gandhi’s Truth, about the complexity of delineating clearly a particular individual’s version of the truth. It was one thing to have Gandhi talk about his idea of nonviolence and quite another to have Erikson subject Gandhi’s claims to concentrated psychological scrutiny. Gandhi’s inner fears, once bared and examined, leave him looking more violent than one might at first have expected.

Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot has demonstrated, in her collection of stories titled I’ve Known Rivers, another genre for shedding light on the accomplishments of African Americans. In that format, Lawrence-Lightfoot is the medium through whom other actors talk about themselves. They relate the stories to her, and she takes the responsibility for structuring the tale and retelling it in her own words. One distinct advantage of this technique is that it avoids the wait until the subject decides to relate the story in autobiographical form. In addition, the intermediate medium may bring expertise and energy to the task that actually facilitate explication and understanding of complex individuals and their achievements.

Still, I can readily see that this form of telling stories has some apparent problems. The intermediary storyteller can easily approach the task with prejudice and then order, emphasize, or diminish events in the subject’s life in a way that ultimately distorts the original version of the individual’s story. There is, as far as I can tell, no way of correcting perfectly the lens through which an individual autobiographer sees the world or the hearing aid through which the storyteller first hears the facts from his subject. That is why there is a natural temptation to use witnesses to buttress certain crucial aspects of another individual’s story, to add external support and weight to the idea that the story is in some way verifiable. Of course, the task is not to overdo it and then recount competing or multiple stories. But there is an unsuppressible urge to know what key bystanders, such as relatives and the spouse, think of an individual’s version of reality. This third genre is what I call storytelling with extra precautions, although it is not clear whether this cautious form of storytelling is necessarily more accurate than other techniques. After all, does anyone seriously believe there is such a thing as an objective spouse?

James Comer’s Maggie’s American Dream and James McBride’s The Color of Water are recent examples of another attempt at recounting the complete tale. Both of these authors tell at least part of their own personal story while relating what they have been told by their mothers. In each case the result is a mesmerizing collage of intersecting and interactional views of two different witnesses to a longitudinal family drama that really has no beginning or end. This fourth genre of telling the individual story certainly has its advantages. If nothing else, it is a shorthand way of getting at roots, at background, while a principal witness to the story is still around to give testimony. The work of these authors definitely makes it clear how truly difficult it is to reconstruct the life story when the major witnesses are all dead. Indeed, their contributions suggest to me that we ought to find some name other than biography to describe the process of storytelling from textual data, from reconstructed artifacts that lack the living human voice.

It is my hope that the methodological weaknesses of each genre of storytelling can be at least outweighed, if not completely overcome, by the achievement of having a story delineated in enough detail to fill the void created by the story’s nonexistence. In other words, when the story’s telling is over, we ought to feel that we are better off for having heard the story and for having enhanced our knowledge of the story’s subject. This is a case where a half loaf is surely better than nothing at all.

It is that feeling of discontent about a missing story that has so drawn me to recount the life of Chester Pierce, an African American psychiatrist who has had a profound effect on American psychiatry and on the thinking of African American psychiatrists and professionals from other mental health disciplines, particularly during the past two decades. Although he has authored substantive scholarship on the task of coping with extreme environments, such as the South Pole, Chester Pierce is probably best known among psychiatrists and other mental health professionals for his theories about how Blacks cope with racist behavior in the United States.

I first met Pierce around 1976 when he was giving a lecture at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. He sat in a chair and talked extemporaneously for almost an hour, in an exquisitely ordered fashion that brought to mind the lectures I had so often experienced during my stay in Europe. He obviously followed the outline he had made in his mind, and his performance prompted one of my Einstein teachers to remark to me that Pierce had done what was expected of distinguished Harvard professors. Obviously, he had performed brilliantly. He had held his audience.

Pierce’s own accomplishments are singularly striking, especially when viewed in their historical context. He was born in 1927; by 1952, he was a graduate of the Harvard Medical School, having already taken his undergraduate degree at Harvard College. He went on to become president of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology in 1978 and president of the American Orthopsychiatric Association in 1983, and he was appointed during his career to the editorial boards of 22 publications and elected to the world-famous Institute of Medicine at the National Academy of Sciences in 1971. In 1969, he was the founding national chair of the Black Psychiatrists of America, and in 1988 the National Medical Association named an annual research seminar after him. By any measure, Pierce has emerged as one of the true lights in twentieth-century American psychiatry, one of the few individuals with substantive standing in both the Black and White mental health communities.

I do not believe there is another American psychiatrist whose theoretical musings about racism are more commonly used in the everyday workplace of mental health clinicians. It is Pierce who has caused so many of us to talk about the constant microtraumas that the racially oppressed individual must endure, of racism as an environmental pollutant, of the state of defensive thinking that so characterizes the oppressed, and of the offensive mechanisms employed by the racist oppressor.

A number of questions naturally emerge when one thinks about Chester Pierce. How has he managed to pull together in his professional thinking so many disparate themes? How, for example, are extreme environments linked to questions of racism? But on a more personal level, who is this man who has managed to graduate twice from Harvard? What is his wife like, and how has he raised his children? How has he personally coped with the microtraumas and macrotraumas of everyday racist actions? What are his views on religion, and for what particular accomplishment would he like to be remembered? I do not believe that a recitation of Pierce’s academic writings would really tell very much about the man. Discussing his life story and excluding his profound thinking in the psychiatric arena would be equally unsatisfactory. I wish to meld together the man and his work and emerge with a cohesive and coherent story about the person everybody likes to call Chet.

I have repeatedly turned over in my mind the question of why I wanted to tell his story and not someone else’s. Certainly, one aspect of the answer has to do with the complicated reasons we all choose our heroes. But another part of the answer relates to the inherent nature of telling other people’s stories—and leads me to the conclusion that I want to do more than tell Chet Pierce’s story. In recognizing that, I’ve come to understand my lack of satisfaction with using any of the other techniques I’ve just described to talk about Chet. They do not allow me to get into Chet’s story, to delve below the words.

It finally dawned on me that I wanted the chance to carry on a sort of argumentative dialogue with him. I recognize that I am seduced by the task of having to hold his feet to the fire, so to speak. For a long time I have contemplated having the opportunity to urge Chet to clarify his positions; and I have so earnestly wanted to explore his logic and question him about whatever contradictions might be found in his thinking. In a way, I have carried out this dialogue so consistently in my mind over the years with no other intellectual in American psychiatry. This has, of course, persuaded me that Chet’s story ultimately has something to do with helping me better conceptualize my own.

After all is said and done, I cannot help noting that in stark Levinsonian terms, that is to say, in the framework so artfully constructed by Daniel Levinson and his colleagues in The Seasons of a Man’s Life, I am entering the culmination of middle adulthood and struggling to complete my age-fifty transitional period. Chet, having been born in 1927, is well into late adulthood and obviously contemplating the age-seventy transition. He must therefore have something to teach me about modification of my own life structure, and I want to discuss it with him. So yes, it’s evident that I never wanted just to tell Chet’s story; I wanted to work his story out, to measure it, to try it on, to figure out which parts are good for me and for other Blacks so earnestly seeking heroes.

Continuing My Dialogue With Chester Pierce

INTRODUCTION TO THE REVISED EDITION

Chester Pierce called me his “biographer,” and sometimes he used the term in introducing me to others. He and I both laughed on occasion when he said it. However, composing the narrative of his life from our exchanges gradually became more important than I had imagined it would be. I found myself in a sustained relationship that lasted until a short time before his death. That is when he became more introspective, and we talked less frequently. I concluded that he wished to be left to contemplate quietly the outcome of his illness. Once the book was finished, and until his withdrawal, we spoke regularly by telephone. He had a long life. Born in 1927 in Glen Cove, New York, he retired at age 70 from his professorship at the Harvard Medical School and the Harvard Graduate School of Education. He died on September 23, 2016, at 89.

I believe Pierce and I first met when he came to deliver a lecture at New York’s Lincoln Hospital around 1976. My training director had arranged for Pierce and me to chat. The encounter was a significant event in my life and the beginning of an excursion with an extraordinary man.

Our telephone discussions, after publication of Race and Excellence and commencement of Pierce’s retirement, were wide-ranging. They swung from the personal to considerations of regional, national, and international issues. He was always interested in family matters, both his and mine. He dwelled often on the good fortune that he had experienced. There was no looking back with regret or disgust. He had no time to chat negatively about individuals who had not been friendly toward him. In that spirit, he often guided the conversation to questions of administrative import related to my activities at work. He had been an academic for many years. This allowed him to get quickly to the crux of problems. He understood transactions and context, the connection of personality structure and power dynamics, and the influence of discrimination of all sorts on systemic structures.

Background

In talking about Race and Excellence, I often emphasize that I was the sole narrator in the project. I formulated the story of the interactions between Chester Pierce and me. The accounts and his voice came through my pen, although I did my best to preserve the authenticity of what he recounted. The promise to be accurate was important. I have always had profound respect for him as mentor, colleague, and friend. He welcomed me as a participant in his civil rights and human rights struggles. We constantly discussed the different geographies in which we operated. I spent extensive time in Barbados between 1980 and 2020 carrying out scholarly projects. I enjoyed constructing life stories of individuals from that island. I saw the people I met there as witnesses to the act of living life in their communities, in their times, in a postcolonial context. (Chester Pierce would be interested to know that a few days ago, Barbados became a democratic republic with a Barbadian president. The ties to Great Britain and its queen have been cut.) Sometimes, we moved in and out of each other’s lives as the years went by. I used a similar approach in my discussions with Chester Pierce, although I was more systematic in talking to him regularly in his Harvard University office for a couple of years. He was in his late sixties at the time, as I remember interviewing him about his impending retirement at age 70.

After years of doing biographical and autobiographical work, I acknowledge my love and respect for the human voice. I have written about narrative for at least the past 25 years. After the 1998 publication of Race and Excellence, I wrote a 2005 family memoir (I’m Your Father, Boy) that was set in Barbados, so influenced by the historical context of British colonialism. In 2010, I published Ye Shall Dream on the life of a deeply religious modern prophet who founded a faith group new to Barbados. These forms of narrative scholarship evolved from courses I taught in African American studies at Yale University. One course focused on Black autobiographies from different social, professional, and psychological perspectives. We discussed slave narratives and stories from pastors, politicians, musicians, dancers, actors, and others. The second course addressed biographical storytelling among Caribbean authors. I melded the themes I cultivated in those two sets of curricula with principles and attitudes acquired in the practice of social and community psychiatry. In addition, I borrowed heavily from anthropological discourse in developing my approach to narrative employed in psychiatry.

In looking at storytelling techniques used by writers, it is evident that authors make use of a variety of aesthetic approaches and structures. Consider briefly, as examples, just three books in the past 25 years from psychiatrists who used narrative as a fundamental structural and communicative platform: City of One: A Memoir by Francine Cournos (Norton, 1999); Women in Psychiatry: Personal Perspectives, edited by D.M. Norris, G. Jayaram, and A.B. Primm (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2012); and The Soul of Care: The Moral Education of a Husband and a Doctor by Arthur Kleinman (Viking, 2019). Cournos issued a fascinating and personal story of her life, characterized by the early loss of both parents and her struggle to adjust and adapt psychologically and socially. It is a compelling example of the classic case history. Women in Psychiatry is an edited collection of stories from female psychiatrists. The thematic emphasis is on the female voice, cultivated in a single profession, although varying in cultural perspective. Kleinman, a psychiatrist-anthropologist, reported on his experience of caring for his wife, who progressively deteriorated functionally and cognitively at the hands of dementia. It is a thoughtful narrative focused on the intricacies of caring for a human being; the horror of witnessing, up close, the systematic deterioration of a loved one; and the absence of compassion in modern medicine. The three books are important and present themes that demand reflection from members of our discipline. Race and Excellence is conceptually different from the texts I have just mentioned. It also contrasts appreciably with my later work in terms of both structure and content. It extended my early thinking about narrative in terms of geography, culture, politics, and social relations. It encompasses two intertwined single lives, more than one unique culture, and more than a single theme. Race and Excellence relies on both biographical and self-portraiture approaches.

Writing about Chester Pierce, I wanted to focus on his individuality. One reader of an early draft of the book wanted me to highlight context more and to dwell on my interpretation of his life. However, I wanted the meaning to emerge from his voice and our interactive discourse. I wished to have him discuss his struggles and the techniques he employed to cope with the displeasures. Then, I would react. I concentrated on capturing his accounts and exploring his conceptualizations of home, work, and leisure; on hearing about who and what he wanted to become, about what blocked or facilitated his dreams. I was interested in his quest to put his stamp on different aspects of public policy. I took pleasure in recounting what he said about understanding the major landscapes he occupied, his relationship with God, the regrets in the life he lived. I could then examine his ideas from different angles. I did my best to focus the light on two Black men, professors of psychiatry, from geographies miles apart, just talking.

Contextualizing the New Edition

It is now more than two decades since the original version of Race and Excellence was published in 1998. The turn into the twenty-first century has been, at least to me, surprisingly eventful, especially in the past few years. That is when events started to push relaxing, mundane matters to the side. Professor Hazel Carby, in a January 2021 essay (“The Limits of Caste,” London Review of Books) talked of the “material and symbolic anxieties of the present” that began around 2016 with the change in the presidency of the United States. Then, “a sense of emergency, of imminent threat” became palpable. Carby described the following 4 years as characterized by “increasing authoritarianism and the rampant spread of White supremacist hatred and violence.”

However, the new Republican president’s rhetoric and actions from 2016 to 2020, while certainly important, did not cause all of the turmoil. We also had the ongoing problem of race relations melded with new discussions of what caste meant. Isabel Wilkerson fueled some of those conversations with publication of her text Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents (Random House, 2020). The question followed: How can we make things better between dominant group members and those lacking fiscal resources and human dignity, the ones at the bottom of the caste ladder? Even the American Psychiatric Association, my main professional group, held meetings over months seeking to contend with the caustic interactions of race and organizational making of policy. I have been stunned, too, by the open political strife and violence in the countries I know best. It seems widespread, this mocking of others on the basis of ethnicity, skin color, social standing, and impoverished socioeconomic resources. There are also the powerful effects of the coronavirus pandemic on the unfolding of this new century. It taught us about our inherent powerlessness in the face of certain natural events and the need to depend on each other at times when selfishness and competition seem embarrassingly useless and irrelevant.

The Reprinted Text

I believe that happenings of the past few years have partly influenced the decision to reprint Race and Excellence. Chester Pierce’s work has illuminated the connection between racial/ethnic discrimination and much of what has been taking place around us. Even recent events, such as the upheaval in Afghanistan and the devastating effects of the earthquake in Haiti, have a connection to the theorizing of Pierce. Both geographic spaces are remarkably obvious extreme environments. In both contexts, physical and mental health are at risk because of the aggravated caste systems operating in the two cultures. The dialogues between Pierce and me that characterize Race and Excellence highlight the linkages between psychiatry and richly racialized national and international cultures. The dialogues have also contributed to increased recognition of Chester Pierce’s contributions to American psychiatry and to common cultural discourse about matters of race and justice. Certainly, his concept of mundane microaggressions as a significant manifestation of discrimination is now in common use. Similarly, we understand better how oppression is manifest in efforts to control another’s space, time, and energy.

The appearance of the new text may coincide with a resurgence of interest in and endowment of the American Psychiatric Association’s Chester M. Pierce Human Rights Award. The award recognizes the extraordinary efforts of individuals and organizations and sheds light on their efforts to promote the human rights of populations with mental health needs. It was originally established in 1990 to raise awareness of human rights abuses but was renamed in 2017 to honor Dr. Pierce. It highlights his dedication as an innovative researcher on individuals living in extreme environments; his advocacy against stigma, discrimination, and disparities in health; and his strong commitment to the concept of global mental health.

Constructing a new introduction for this edition of Race and Excellence helps me to see the influence of Pierce on my own work. At the time I decided to write about his life, I was interested in the connection between life stories and the Black community in the United States, as well as the place of Blacks in organizations such as universities. I thought that focusing on him was, to some extent, opening a window onto Black life and culture. The melding of his biography with certain features of my own story was a unique way, I thought, of testing certain ideas about Black life cross-nationally. Those interests of 20 years ago remain. However, they are now linked to other sociocultural experiences, such as the effects of climate change, the raucous presence of the coronavirus, and the persistent problems provoked by ethnicity and class in America and elsewhere.

Imagining a Continuing Dialogue

Chester Pierce and I should be discussing current matters now, periodically, say, once a month. I would mention how friends were coping in Barbados or France. He would theorize more broadly about how the Turks were doing and why the Chinese were strategically making their moves to outfox the Western politicians. Chet, which was my term of endearment for him, would point out that the COVID-19 pandemic, with its isolation and death, provoked reactive responses of institutions to its dominance. He would perhaps suggest that the coronavirus has taught us anew about reordering our social and economic priorities. It has forced us to think about the meaning of mundane rituals and values we have long taken for granted.

I have wondered what he would think of my being troubled by the renewed reliance on the public lie and the enhanced emphasis on disinformation all around us. I am not accustomed to this use of mendacity for all to see. I am familiar with the hesitant use of deceit and sleight of hand in private discourse, under wraps, so to speak. However, I am not friends with the technique of publicly promoting demonstrably false concepts such as the notion that the coronavirus is easily controlled and a mere passing annoyance. I also mention here the problem of monster stories. I borrow the term from Gwen Adshead, a British psychiatrist-friend of mine who worries about its currency and ubiquity. She referred to these stories in her work on serious crimes committed by people living with severe mental illness. Some observers paint these individuals as concentrated villains, evil and destructive. The person lacks even a scintilla of redeeming possibility, and the portrait is intended to frighten the community. It is sad when one uses the monster story to demean the other and to gain advantage over the individual who is portrayed as almost less than human. Monster portraits are especially obnoxious when linked with fake news about an individual. Chester Pierce was concerned about these techniques and recognized their use at times against minority groups. I was familiar with their use against migrants, especially when I heard tales about Caribbean friends trying to make a new life in London or New York. I also saw the phenomenon up close when serving as a soldier in Vietnam. Then, the image of the Vietnamese as monsters was at the core of American rhetoric.

I would tell Chet about having attended a 2021 reception in Birmingham, one of the United Kingdom’s most diverse cities. I had the good fortune to meet a member of the worldwide Quaker movement. We discussed his religious group’s tenets and basic rituals. Then he summarized his belief that humanity is now at a “point of great turning.” He saw the possibilities of cooperatively confronting the major challenges of climate change; race-based, gender-based, and class-based injustice; general inequality; and violence. He maintained that his views were undergirded by the biblical text from Micah 6:8: “He has shown you, O man, what is good. And what does the Lord require of you but to act justly, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God?”

Chet and I could easily emphasize the religious dimension of my new friend’s ideas. However, it seemed to me that one could see religion as representing a thin patina on notions of living. I am thinking here of Greg Epstein, the humanist chaplain at Harvard University, and his provocative text, Good Without God (William Morrow, 2009). The point is that one can accomplish good in life by seeking constructive purpose, treating others with compassion, and building community. Similarly, my British friend saw the problems around him as existing across all the continents, irrespective of citizens’ religious beliefs. He offered an open, collaborative approach to the solutions that, in his view, demanded cooperation from each of us. Similarly, Chet talked about the principles by which we could live, without framing things in a religious context. He was preoccupied with the implementation of justice in multiple domains. Furthermore, those who knew him spoke easily of his humility and remarkable generosity. He and I focused, from time to time, on his churchgoing, and he encouraged my research on Black church rituals and the role of the Black church as a healing community. I also had the impression that his spiritual life was private and rarely advertised. Nevertheless, he had little patience for religious ideas that divided people from their neighbors, promoted our vanity, increased competition, and visibly left one group or another at the bottom of the caste ladder. I recognized that the failings of organized religion did not stop him from appreciating the inherent therapeutic value of faith-based communities.

Reflecting on these points, I gradually understood that Chet visualized greater breadth in the portrait of the world around him than I appreciated at first. He liked the combination of narratives from different cultures, products of dialogue between him and others sometimes, and related to others he was observing. He enjoyed the focus on individuals’ reactions to experiences and events in their lives. The contextual background was the cultural fabric weaved around people. On an international scale, powerful forces influence the formation of our backgrounds. Some examples are racialized and class-based political disputes, identity politics that defy easy resolution, and pervasive feelings of individual disenchantment. There is also the search for a sense of human dignity and personal worth and uncertainty about the future in terms of health and security. The pandemic has turned those catalysts upside down and produced extensive dislocation in the general culture. Chet did not know of this latest plague, but he was ahead of most of us because of his interest in extreme environments and the challenge to control climate’s independence.

Readers and the Text

I hope that, regardless of one’s vantage point, the interactive dialogue between Chester Pierce and me appeals to readers and leads to reflection about our conversations. We discuss our life experiences and engage in quiet meaning-making. Our exchanges may require some concentration and a commitment to the adventure of reading about our lives that unfolds in contrasting times and places. The two lives have some similarities and intriguing differences. There is, too, the privilege of seeing how we have confronted Eriksonian events in our lives and then agreed to recount our experiences through the power of stories. Borrowing language from Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub in their popular text, Testimony (Routledge, 1992), the life stories I narrate “cover a whole spectrum of concerns, issues, works, and media of transmission, moving from the literary to the visual, from the artistic to the autobiographical…to the historical” (p. XV). Stories always have the potential to serve as models for contemplation of reactions to turmoil and dislocation. They also serve well as a culture-based way of framing future developments in public policy. People’s life stories and experiences chart a course for political and legislative decision-making about race and health, race and education, race and criminal justice. Readers of Race and Excellence will confront the written experiences of others and also think about whether the accounts make sense in their imagination. Readers will think about their own lives and whether the stories usefully fit them or are just temporary fantastical flights away from their realities.

A colleague recently spoke to me of an early speech given by Chet to a group of educators that was published in 1972 under the title of “Becoming Planetary Citizens” (Childhood Education 49:58-63, 1972). In the piece, Chet tackled the problem of preparing young students for the twenty-first century, to live in a world as planetary citizens. He envisaged their being mindful of interacting with others beyond national geographic boundaries and being acutely aware of the need to be collaborative rather than simply competitive. That would, he thought, require a higher level of general knowledge about the world and its nations. This would produce more supergeneralists seeking the status of planetary citizenship. He argued it would augment the pursuit of hope in the place of selfish and destructive competition. With this objective in mind, Chet saw the need for educators to focus on such matters as conflict resolution, decision-making, the international spread of infectious diseases, and the effects of technology on life everywhere.

The characteristic features of this speech, published 50 years ago, were based on thinking broadly about the dignity of individuals. One sees in it the imperative of understanding how local action produces repercussions across the globe. Chet argued in this article that racism is the pernicious impediment to achieving the desired objective of collaborative citizenship. Racism is a pollutant that interferes with interactive and productive fellowship. Seeing people in your neighborhood as the other, that individual you do not know and whom you fear and see as different and inferior, automatically makes it harder to establish global interactions that are mutually beneficial. That is why Chet talked repeatedly of seeing travel as a way of exploring mutual humanity. I believe, too, that there is a connection between these futuristic, inter-nation ideas of Chet and the hope that we will eventually deal with each other nonviolently.

Unfinished Business

I confess that I have had some misgivings about unfinished business with Chet. There are two matters that I have turned over in my mind on repeated occasions. The first concerns his tenacious and repetitive conclusion that a sense of belonging at Harvard always eluded him. This was perhaps the most problematic claim that emerged in our discussions. I took note of facts and incidents that seemed to establish his grounding at Harvard. He had obtained his bachelor’s degree there, played on its varsity football team, attended its medical school, held a professorial appointment in the School of Education and the Medical School for many years. He and I had walked around Cambridge, dined at the small city’s numerous ethnic restaurants, and encountered other faculty members in the street who greeted him deferentially. He had taken me to the Harvard Faculty Club, where the rituals and architecture combine to make its users feel they have certainly arrived, even if they are uncomfortable in its precincts. He had also told me about the portrait of him that Harvard had commissioned, to be hung within some university space.

Surrounded by such evidence, I found it hard to grasp the legitimacy of his assertion. It felt like the statement of a military strategist who has spent years planning the effort to take a city only to state, after winning the war and taking up residence in the land he has conquered, that he could never enjoy living there. Chet was interred without our having returned to this conversation. We also did not review my latest book, Belonging, Therapeutic Landscapes, and Networks (Routledge, 2018), in which I articulated my hesitancy in making claims about belonging at Yale, after teaching there for almost 40 years. In the interim, I had read the important essay-letter “To Sit at the Welcome Table” by Harvard’s former president, Drew Faust (Harvard Magazine, July 2014). Faust documented Harvard’s efforts over centuries to make minority group members feel tolerated and barely welcome at the university. She pointed out the changes wrought in recent years to change that aspect of Harvard. She referred to the inspiration in Langston Hughes’ poem “I, Too,” and she conjured up the image of Harvard as a welcome table. She promised sustained renewal of the efforts to guarantee everyone at Harvard an honored seat at the table. It is of considerable interest, too, that Yale and other universities have recently been discussing publicly their considerable participation in the institution of slavery. Chet would have had much comment to make about this happening, had he lived to witness it.

The writings of scholars at these distinguished institutions often ring with sincerity of purpose and commitment. It is easy to believe them. On the other hand, those a little lower on the totem pole of university administration can make decisions that convey a surprising lack of compassion and concern for their charges’ dignity. I was concerned about the virulence of competition and emphasis on self-interest at Yale. I understood that the idea of planetary citizenship, fueled by collaboration and mutual respect within a community of individuals with common interests, was not popular in the spaces I frequented. Having said that, it is a pleasure to note that changes have been made, and progress is in the air. The national conversation about race matters has left its mark in the ivory tower of academia.

The second piece of unfinished business that I have pondered from time to time in connection with Chester Pierce has been the subject of self-exile. Black people have been energetic participants in the phenomenon of geographic migration over many generations. Scholars have discussed, for example, the early- and mid-twentieth-century movement of Southern Blacks in the United States to cities in the North and West. Similar consideration has been given to Caribbean Blacks and their relocation to the United Kingdom and the United States during the 1950s and 1960s. The 2021 reissue of William Gardner Smith’s The Stone Face by the New York Review of Books has rekindled interest in the self-exile of Black artists and other intellectuals from the United States to France in the twentieth century. It is of some note, too, that one of the critics of my scholarship once labeled me a Caribbean exile. I have always assumed that the label conveyed some unexplained meaning about my having settled in North America from Barbados and later studying medicine in France. In his scholarly introduction to the new edition of The Stone Face, Adam Shatz focused on the exile of people such as Richard Wright, James Baldwin, the cartoonist Ollie Harrington, William Gardner Smith, Josephine Baker, and Sidney Bechet. Shatz commented that Paris offered to these individuals a refuge from segregation and discrimination and opened a more normal everyday life to them. Part of the mundane normalcy included opportunities to interact with everybody, to enjoy acceptance by shopkeepers and police officials, and to cultivate a strong ethnic and personal identity.

Shatz was quick to point out that this common exile to France, which occurred between the 1920s and the American Civil Rights years, had its own dangers. American Blacks’ welcome by French authorities did not mean that France had no caste-based discrimination in operation. Indeed, France was shown to operate a caste ladder effectively, with Algerians and Black Africans on the bottom. The other problem was that leaving the United States behind did not efface the American problem. All it possibly meant was that those who departed U. S. shores relinquished civil rights efforts to those who remained at home. The issue became a serious difficulty, in terms of philosophy, policy, and ethics, for the group of exiles. That is why several of them returned home to participate in the civil rights activities and clear their names of any suspicion that they had abandoned the struggle to others.

I did not directly discuss the self-exile question with Chet. Nevertheless, we did talk about whether participation in resolving these moral dilemmas was mandatory. As a general principle, he affirmed the obligation to give something back to the society in which one was reared. He stated that doctors, because they had received so much in terms of esteem, prestige, and salary, should contribute some of their time, energy, and money to those who were less fortunate. He lived by example in these matters. So, in his terms, he put a brick regularly toward construction of civil rights and human rights efforts. He did so without fanfare. The unwelcome noise distracted him.

He often reminded me that evaluating the reasons others give for their decisions assumed that the critics had complete and accurate knowledge of what drove the actions of those under scrutiny. Chet believed that those evaluations were often wrong. So he affirmed his commitment to struggling against the oppression of Blacks, both at home and abroad. He defined the struggle in international terms, or in global terms, as is now the preferred terminology. We never discussed the matter of searching for Zion outside the United States. However, I did not believe that he saw some other country as the proverbial land of milk and honey, at least as far as race relations were concerned. In Search for Zion (Atlantic Press, 2013), Emily Raboteau, for example, takes the reader around the globe and returns to the possibility that home is within oneself. Certainly, some of the Paris self-exiles reached the same conclusion and found home back in the United States or in some other country. A colleague did ask me whether Chet’s extensive traveling to fulfill his scholarly commitments may have represented a form of respite or self-imposed distancing from the stress of the unceasing struggle against injustice. On reflection, I must accept the possibility of such a hypothesis. These days, it comes under the heading of self-care. I can confirm that Chet was very concerned about the heavy price paid by the Black body and mind in daily racialized living.

Adam Shatz points to an important finding in the work of William Gardner Smith: the rootlessness that often accompanies self-exile. I observed how Chet participated vigorously in civil rights work at home. I concluded easily that such activity, coupled with his clinical and intellectual efforts in medicine, provided a solid identity base for him. This was reinforced by his family and marriage ties. What may one make of his stated lack of belonging at Harvard, an institution that provided him so much pleasure and honor? Is this a form of rootlessness that comes from the chronic pain inflicted in the struggle on behalf of the oppressed? I ask because I know that the small incremental successes achieved in the years-long civil rights struggles can be hard to take. Chet mentioned that idea to me on several occasions in his neurophysiology theorizing about the stress on those in the struggle. The grand victory is the rare conclusion, and it is shared by only a few. I wish I had been able to explore this matter in greater depth with Chet. Such thoughts do keep him alive.

Ezra E.H. Griffith, M.D.

December 2021