Psychosomatic medicine/consultation-liaison psychiatrists are routinely asked to perform evaluations and make treatment recommendations in challenging medical and ethical situations. This often includes but is not limited to life-threatening and emotionally charged scenarios such as refusal of recommended treatments, assessment of dangerousness, conflicts among involved parties in an end-of-life situation, and medical futility issues. Even in the hospitals where ethics consultation is routinely available, psychiatric consultation is commonly requested either before or in conjunction with evaluation by a medical ethics consultant.

In some cases, a true ethical dilemma is disguised as a consultation request for psychiatric evaluation for suspected psychopathology, or vice versa (

1).

In addition, psychiatrists consulted in general hospitals are often perceived to be well versed in ethics and may be asked to serve on the hospital bioethics committee or institutional review boards (

2). While most psychiatrists are not formally trained in bioethics, it is essential for psychiatrists who work in the medical setting to become familiar with the common ethical principles and framework used to assist the ethical analysis of commonly encountered ethical dilemmas.

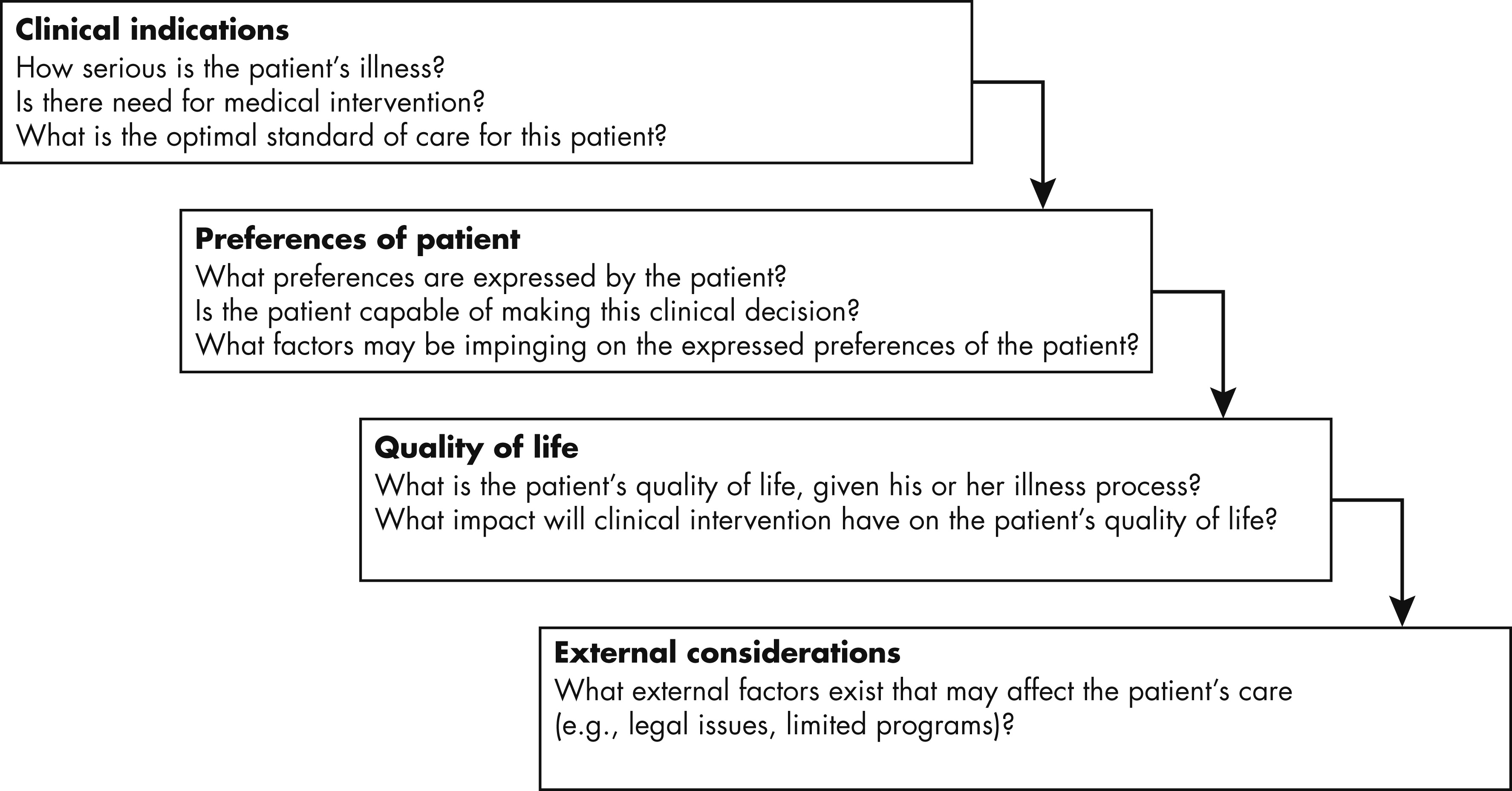

Wright and Roberts (

3) advocate the use of Four Topics Method (

4) to help with ethical decision-making strategy for patients in medical settings (see

Figure 1). In this method, each case is approached through the analysis of 1) medical indications, 2) patient preferences, 3) quality of life issues, and 4) contextual features. It is important to note that the medical indications criterion has precedence over other considerations to ensure that patients are offered an appropriate standard of care, free from prejudice or contextual factors that may be threatening to the patient’s well-being. Other ethical principles, such as Beauchamp and Childress’ four cardinal principles of biomedical ethics (autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice [

5]), are applied to issues as they arise in the analysis (

3). In fact, in the Four Topics Method, through eliciting and understanding patient preferences, the clinician applies the principles of autonomy and respect for persons to the case conceptualization.

Perhaps the most common ethical issue with which psychiatrists working in the medical setting are called upon to consult is an evaluation of patient’s capacity to refuse care. Decisional capacity has been defined to consist of four standards:

1.

Ability to communicate preference;

2.

Ability to understand information necessary for the specific decision at hand;

3.

Ability to appreciate the implications and significance of the provided information or the choice being made; and

4.

Ability to reason by weighing and comparing options as well as consequences of the potential decision (

5).

Much has been written on this specific topic (

5,

6), but it is worth emphasizing that “informed consent” is comprised of three critical elements: information supervision, decisional capacity, and voluntarism capacity (

5). Roberts et al. (

3) have recommended Drane’s “sliding scale” model as a potential tool to help determine the patient’s decisional capacity, especially when the decision potentially carries some risks. According to the sliding scale model, the patient’s capacity varies according to the potential risk/benefit ratio of the decision (i.e., a procedure with high risk and questionable benefits would require a more rigorous “threshold” of decisional capacity).

In the following sections, we will describe three case scenarios adapted from actual cases using the Four Topics Method described earlier.

Case 1: Refusal of Care and Capacity Evaluation

Ms. Y was a 30-year-old Hispanic female with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus and chronic abdominal pain who was admitted for the evaluation and treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis. A conflict arose when Ms. Y requested intravenous hydromorphone that the medical team did not feel was indicated and thus declined. Ms. Y then threatened to leave against medical advice. Psychiatry was consulted emergently to evaluate whether the patient had the capacity to make that decision and to “put her on a psychiatric hold” if she did not have the capacity. The patient refused to talk with the psychiatrist at bedside but agreed to stay for treatment after the team provided her with some pain medication and agreed to call for consultation with a pain specialist. During that time, an ethics consultation was also obtained. Ms. Y was seen by the ethics consultant a few hours later, who determined that she had capacity to leave against medical advice if that was her choice. The patient agreed to see a psychiatrist the following day for depression provided that the psychiatrist was female, but she subsequently refused any recommended psychiatric treatment for depression or possible substance abuse. She was discharged from the hospital the following day when her blood sugar normalized.

Ethical Formulation

Medical indication: This is a patient who has type 1 diabetes mellitus currently complicated with diabetic ketoacidosis that is expected to fully resolve with treatment. She has possible depression and history of chronic pain as well as possible narcotics misuse.

Patient preferences: Patient understands her diabetes and the need for diabetic ketoacidosis to be treated. She would not talk to a psychiatrist because she was very upset and was offended that “people were treating me like I'm stupid.” She also reports that because of prior abuse in her life, she is more comfortable talking with women than men (the initial psychiatric consultant was a male resident). Since reaching agreement and receiving some pain medication, she agrees to cooperate with treatment. She no longer has plans to leave against medical advice but is very reluctant to speak with a psychiatrist again.

Quality of life considerations: She lives with family, works as a waitress, does not want to miss work, and wishes to take care of her family.

Other contextual issues: Her history of pain medication use or misuse was not well documented because she normally received care elsewhere.

This case illustrates the common resolution of the issue of a patient threatening to leave against medical advice. Often this resolves when the treating team and staff members attempt to communicate with the patient in a nonjudgmental manner, and at the same time address and empathize with the patient’s needs. In this particular case, the situation deescalated when the team agreed to include a pain evaluation and provide the patient with medication to relieve her acute pain during the evaluation. In the event that conflict arises, attempts should be made to educate and persuade the patient to remain in the hospital. However, it is important to note that when the patient is deemed capable of making a decision to leave against medical advice and not in acute danger to self from mental disorder, psychiatric hold should not be used as a means to keep the patient in the hospital for medical treatment, however tempting this might be for the treating physicians. Beneficence, an obligation to benefit patients and to seek their good, requires an appreciation of a patient’s preference and best interests. However, the good of the patient may be different from the medical good (

1).

Case 2: Conflicting Roles of the Psychiatrist: Beneficence Versus Justice

Ms. N was a 23-year-old woman with a history of extensive polysubstance abuse in remission and cystic fibrosis for which she received her first lung transplant. During her pretransplant psychosocial evaluation, she signed an abstinence contract. Two years after her transplant, she was referred to a psychiatrist affiliated with the lung transplant program for treatment of her anxiety disorder and interpersonal issues. Her treatment plan included anxiolytic medication and psychotherapy. Six months after establishing her care with the psychiatrist and engaging in weekly psychotherapy, Ms. N developed a chronic rejection and quickly deteriorated. It came to light that although adherent with her immunosuppressant medications, Ms. N. had been using edible marijuana “to boost her appetite” and had several binges of alcohol “to deal with relationship stress.” Her treating psychiatrist was asked to comment on the patient’s psychosocial suitability for another transplant. The psychiatrist explained to the lung transplant team with which he was affiliated as a consultant that he could not remain unbiased in this case, since he felt that his duty was to advocate for the patient. However, he also objectively stated his concerns about substance relapse and reminded the team that this is a poor prognostic factor. Her psychiatrist indicated that if a formal and unbiased opinion was needed, a separate party should be consulted.

Ethical Formulation

Medical indication: Patient with worsening rejection needs a second transplant. Contributing psychiatric history includes an anxiety disorder and history of polysubstance abuse with recent relapse possibly contributing to her organ failure.

Patient preference: The patient would like to be listed for a second transplant. She expresses her apologies for the relapse and promises not to use any recreational substances again.

Quality of Life: Patient’s quality of life is severely compromised by her worsening health and her only true hope for improving her quality of life and prolonging her life is a second transplant. Her prognosis without the transplant is at most a few months.

Other contextual issues: There is a limited supply of organs. Most programs list substance relapse as an absolute contraindication for a second transplant. Psychiatrist is torn between his role of advocating for the best interests of the patient and the role of consultant to the transplant team, evaluating psychosocial risk of the patient.

This case demonstrates conflicts between psychiatrist’s dual roles, one as the patient’s therapist who has the patient’s best interests in mind and the other as a consultant to the transplant team where his role is to make the best evidence-based psychosocial recommendations, given limited supply of a much needed resource. Careful medical and psychosocial criteria are in place to ensure fairness, justice, and maximum benefit for the individual and society at large. Psychosocial factors, such as nonadherence, social support, psychiatric comorbidities, and substance abuse, have been shown to correlate with posttransplant outcomes (

7). This might become an especially poignant dilemma in situations where few individuals can provide particular expertise in a specialized area of psychiatry or medicine. It is important to recognize and acknowledge these conflicting roles and if possible, extricate the provider from this dilemma, making clear which role the provider will be acting in.

Case 3: Helping a Patient Make the Best Decision According to His Values

The patient was a 34-year-old single man of Pacific Island origin with severe heart failure complicated by renal failure who was being maintained on multiple inotropes. Psychiatry was consulted to evaluate the patient’s candidacy for ventricular assistive device implantation and potentially a heart transplant. Specific concerns included the patient’s ambivalence about these interventions, his significant anxiety with regard to care associated with the ventricular assistive device, and possible visual hallucinations. Patient was initially diagnosed with delirium for which he was successfully treated, then later demoralization which was addressed with psychotherapy and symptomatic medication management. As the patient’s mental status cleared and he became engaged with the psychiatric team, he was able to express his ambivalence about life-saving procedures that seemed not to be consistent with his own values. Patient shared that the only life that he saw worth living was one free of physicians, full of work and family life, back in his home country, and not restrained by life-long restrictions on diet, drink, and medications. This was clearly not an option if he were to undergo ventricular assistive device placement and eventually heart transplantation. Thus, he did not think that ventricular assistive device placement would return the quality of life he sought. After multiple discussions with the psychiatry and primary cardiac team aimed at elucidation of his values and principles, he was found to have full capacity to decline ventricular assistive device placement and his care was transitioned to comfort care measures. Patient was able to spend his last days in emotional peace, physical comfort, and the company of his family as well as enjoying activities of eating and drinking with no restrictions, both luxurious and gratifying to him.

Ethical formulation

Medical indication: Patient is a young man with end-stage heart failure, unable to be weaned off of inotropic support, with the only chance of survival being implantation of a ventricular assistive device or heart transplant.

Patient preference: Patient expresses that the requirements of taking care of the ventricular assistive device or a heart transplant are not consistent with what he considers a good quality of life and thus he does not see the benefit of these invasive procedures for him.

Quality of life issues: Patient has been on disability for many years, unable to work, consumed by doctors’ appointments. He does not see a life full of doctor visits and orders as a quality existence.

Other contextual considerations: Involved physicians have strong counter transference when taking care of a young person who can medically benefit from invasive interactions but rejects them. Patient had strong pressure from his family to consider the ventricular assistive device and heart transplant.

This case highlights the common conflict between patient’s autonomy and physician duty to beneficence. In this case, although the initial question to the consulting psychiatrist was to address psychiatric symptoms and to evaluate the patient for psychosocial candidacy for the invasive intervention, the real goal of the consult became helping the patient elucidate and articulate his life values and goals and help advocate these goals to the treatment team, even if these values led to the decision conflicting with the physician’s urge “to save the patient.”

Conclusions

Psychiatrists who practice in medical settings are often asked to provide not only psychiatric recommendations but also suggestions for ethical issues involving medical-surgical patients. Becoming familiar with core ethical principles and ethical decision-making strategy such as the Four Topics Method will help the clinician and other providers in providing high quality care grounded in medical ethics principles.