Anxiety and depressive disorders are highly prevalent (

1,

2) and are associated with a substantial loss of quality of life for patients and their relatives (

3,

4), high levels of service use, substantial economic costs (

5-

7), and a considerable disease burden for public health (

8). Effective treatments are available for these disorders, including several types of psychotherapy and antidepressant medication (

9-

11). Although psychotherapy and antidepressants are about equally effective for most anxiety and depressive disorders (

12), there is some evidence that combined treatments may be more effective than each of these treatment alone (

13-

15). At the same time, however, an increasing proportion of patients with mental disorders in the past decade have received psychotropic medication without psychotherapy (

16,

17). It is important, therefore, to examine whether this has negative effects on the quality of care.

We conducted a meta-analysis of studies comparing pharmacotherapy alone with combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Although some earlier meta-analyses have examined this question, these were all aimed at one disorder, especially depression (

13-

15) and panic (

18,

19). For some other disorders – e.g., social anxiety disorder (SAD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) – several primary studies have been conducted, but these have not yet been integrated into meta-analyses. The main goal of this paper, therefore, is to provide an overall meta-analysis of studies comparing antidepressant medication with combined treatment for anxiety and depressive disorders. We also examined whether differences between combined treatment and placebo only were larger than those between combined treatment and pharmacotherapy, in order to determine the relative contribution of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy to the effects of combined treatments.

Methods

Identification and Selection of Studies

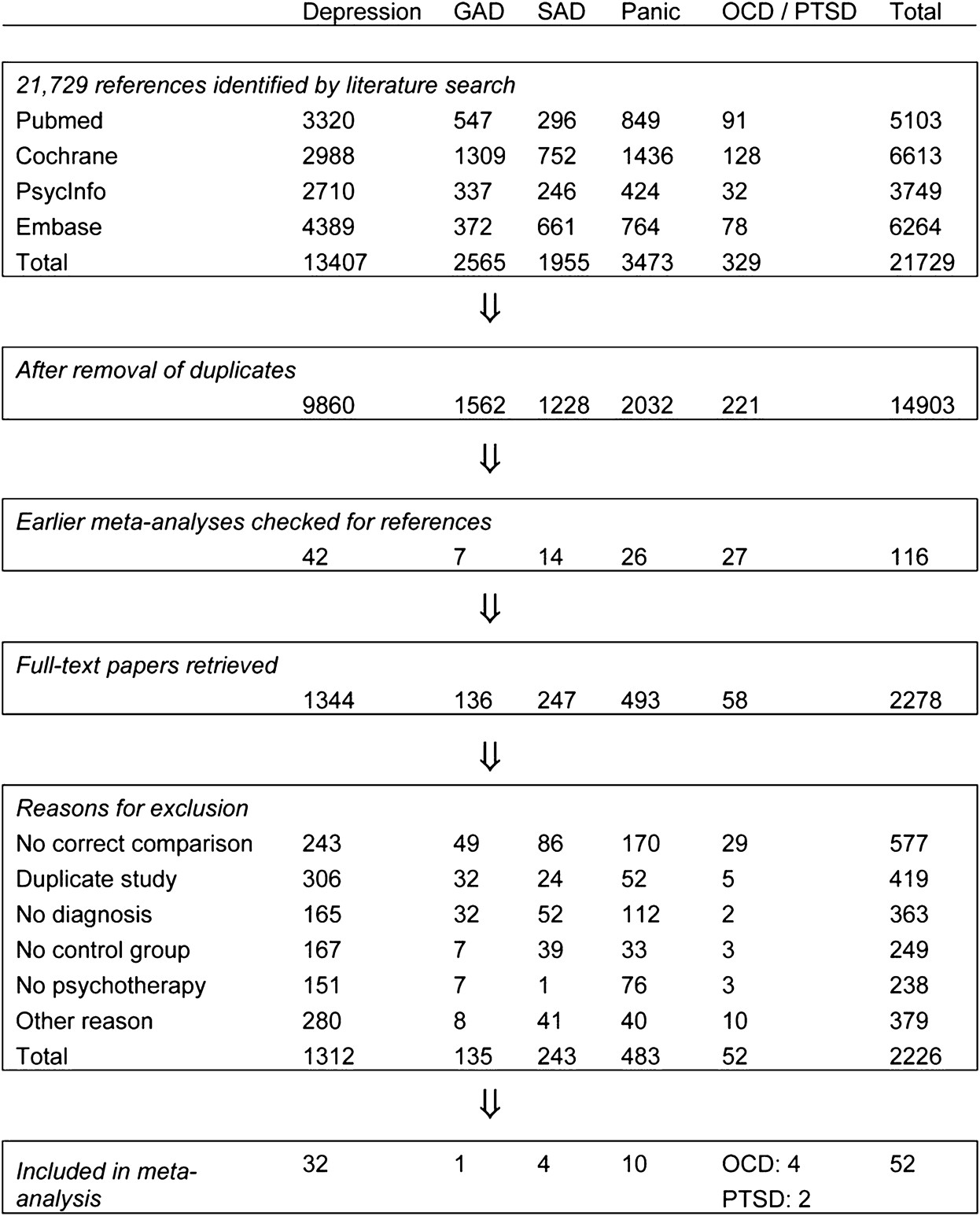

We used several strategies to identify relevant studies. We searched four major bibliographical databases (PubMed, PsycInfo, Embase and the Cochrane database of randomized trials). We first developed a search string for psychotherapy with text and key words indicating the different types of psychotherapy and psychological treatments. This search string was combined with search strings indicating each of the disorders we included: major depression; dysthymia; generalized anxiety disorder (GAD); SAD; panic disorder; OCD; post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We limited our search to randomized controlled trials. We also checked the references of 116 earlier meta-analyses of psychological treatments of the disorders (

Figure 1).

We included randomized trials in which the effects of treatment with antidepressant medication were compared to the effects of a combined antidepressant medication and psychological treatment in adults with a depressive disorder, panic with or without agoraphobia, GAD, SAD, OCD or PTSD. Only studies in which subjects met diagnostic criteria for the disorder according to a diagnostic interview – such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), or the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) – were included. Studies on inpatients, adolescents and children (below 18 years of age) were excluded. We also excluded maintenance studies, aimed at people who had already recovered or partly recovered after an earlier treatment. Studies in English, German, Spanish, and Dutch were considered for inclusion.

Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

We assessed the validity of included studies using the “Risk of bias” assessment tool, developed by the Cochrane Collaboration (

20). This tool assesses possible sources of bias in randomized trials, including the adequate generation of allocation sequence; the concealment of allocation to conditions; the prevention of knowledge of the allocated intervention (masking of assessors); and dealing with incomplete outcome data (this was assessed as positive when intention-to-treat analyses were conducted, meaning that all randomized patients were included in the analyses). Assessment of the validity of included studies was conducted by two independent researchers, and disagreements were solved through discussion.

We also coded participant characteristics (disorder; recruitment method; target group); type of antidepressant that was used (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, SSRI; tricyclic antidepressant, TCA; serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SNRI; monoamine oxidase inhibitor, MAOI; other or manualized treatment including several antidepressants); and characteristics of the psychotherapies (format; number of sessions; and type of psychotherapy). The types of psychotherapy we distinguished were cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), and others. Because most CBT therapies used a mix of different techniques, we clustered them together in one large family of CBT treatments. We rated a therapy as CBT when it included cognitive restructuring or a behavioral approach (such as exposure and response prevention). When a therapy used a mix of CBT and IPT, we rated it as “other”, along with other therapeutic approaches (such as psychodynamic therapies).

Meta-Analyses

For each comparison between a pharmacotherapy and the combined treatment group, the effect size indicating the difference between the two groups at post-test was calculated (Hedges’ g). Effect sizes were calculated by subtracting (at post-test) the average score of the pharmacotherapy group from the average score of the combined treatment group, and dividing the result by the pooled standard deviation. Because some studies had relatively small sample sizes, we corrected the effect size for small sample bias (

21).

In the calculations of effect sizes in studies aimed at patients with depressive disorders, we used only those instruments that explicitly measured symptoms of depression. In studies examining anxiety disorders, we used only instruments that explicitly measured symptoms of anxiety. If more than one measure was used, the mean of the effect sizes was calculated, so that each study provided only one effect size. If means and standard deviations were not reported, we used the procedures of the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (version 2.2.021) to calculate the effect size using dichotomous outcomes; and if these were not available either, we used other statistics (such a t-value or p-value). To calculate pooled mean effect sizes, we used the above-mentioned software. Because we expected considerable heterogeneity among the studies, we employed a random effects pooling model.

Because the standardized mean difference (Hedges’ g) is not easy to interpret from a clinical perspective, we transformed these values into the number needed to treat (NNT), using the formulae provided by Kraemer and Kupfer (

22). The NNT indicates the number of patients that have to be treated in order to generate one additional positive outcome (

23).

We also calculated the relative risk (RR) of dropping out from treatment in pharmacotherapy compared with combined treatment. To compare the long-term effects of the two treatments, we calculated the RR of having a positive outcome at follow-up.

As a test of homogeneity of effect sizes, we calculated the I

2 statistic, which is an indicator of heterogeneity in percentages. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and larger values indicate increasing heterogeneity, with 25% as low, 50% as moderate, and 75% as high heterogeneity (

24). We calculated 95% confidence intervals around I

2 (

25), using the non-central chi-squared-based approach within the Heterogi module for Stata (

26).

We conducted subgroup analyses according to the mixed effects model, in which studies within subgroups are pooled with the random effects model, while tests for significant differences between subgroups are conducted with the fixed effects model. For continuous variables, we used meta-regression analyses to test whether there was a significant relationship between the continuous variable and the effect size, as indicated by a Z-value and an associated p-value.

We tested publication bias by inspecting the funnel plot on primary outcome measures and by Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure (

27), which yields an estimate of the effect size after the publication bias has been taken into account. We also conducted Egger’s test of the intercept to quantify the bias captured by the funnel plot and test whether it was significant.

Results

Selection and Inclusion of Studies

After examining a total of 21,729 abstracts (14,903 after removal of duplicates), we retrieved 2,278 full-text papers for further consideration. We excluded 2,226 of the retrieved papers. The flow chart describing the inclusion process, including the reasons for exclusion, is presented in

Figure 1. A total of 52 studies met inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis (

28-

79). Selected characteristics of the included studies are reported in

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

In the 52 studies, 3,623 patients participated (1,767 in the combined treatment conditions and 1,856 in the pharmacotherapy only conditions). Thirty-two studies were aimed at depressive disorders (22 on major depression, including one that was aimed at patients with both major depression and OCD; 5 on dysthymia; and 5 on mixed mood disorders) and 21 at anxiety disorders (10 on panic disorder with or without agoraphobia; 4 on OCD; 4 on SAD; 2 on PTSD, and one on GAD). Most studies (n = 32) recruited patients exclusively from clinical samples, and were aimed at adults in general instead of a more specific population (such as older adults or patients with a comorbid somatic disorder).

Most psychotherapies belonged to the family of cognitive and behavioral therapies, while nine studies examined IPT, and the remaining 10 examined other therapies (including psychodynamic therapies). The number of treatment sessions ranged from 5 to 56, with most therapies (n = 36) having between 10 and 20 sessions. The antidepressants that were examined in the studies included SSRIs (n = 22), TCAs (n = 13), SNRIs (n = 3), MAOIs (n = 4), and treatment protocols with different types of antidepressant medication (n = 10).

Most studies were conducted in the US (n = 20), or Europe (n = 19). Two papers were published in German, the rest in English.

Quality Assessment

The quality of the studies varied (

Table 1). Twenty-one studies reported an adequate sequence generation, while the other 31 did not. Nineteen studies reported allocation to conditions by an independent (third) party. Thirty-nine studies reported blinding of outcome assessors or used only self-report outcomes, whereas 13 did not report blinding. Thirty-one studies conducted intention-to-treat analyses (a post-treatment score was analyzed for every patient even if the last observation prior to attrition had to be carried forward or that score was estimated from earlier response trajectories). Thirteen studies met all four quality criteria, another six studies met 3 criteria, while the remaining 33 studies met two criteria or less.

Effects of Combined Treatment Versus Antidepressants Only

The overall mean effect size indicating the difference between pharmacotherapy only and combined treatment of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy at post-test for all 52 studies was 0.43 (95% CI: 0.31-0.56) in favor of the combined treatment. This corresponds to a NNT of 4.20. Heterogeneity was moderate to high (I

2 = 64; 95% CI: 52-73). After exclusion of three possible outliers with extremely large effect sizes (g > 1.5;

Table 2), the effect size was somewhat smaller (g = 0.37; 95% CI: 0.27-0.47; NNT = 4.85), but heterogeneity was reduced to a moderate level (I

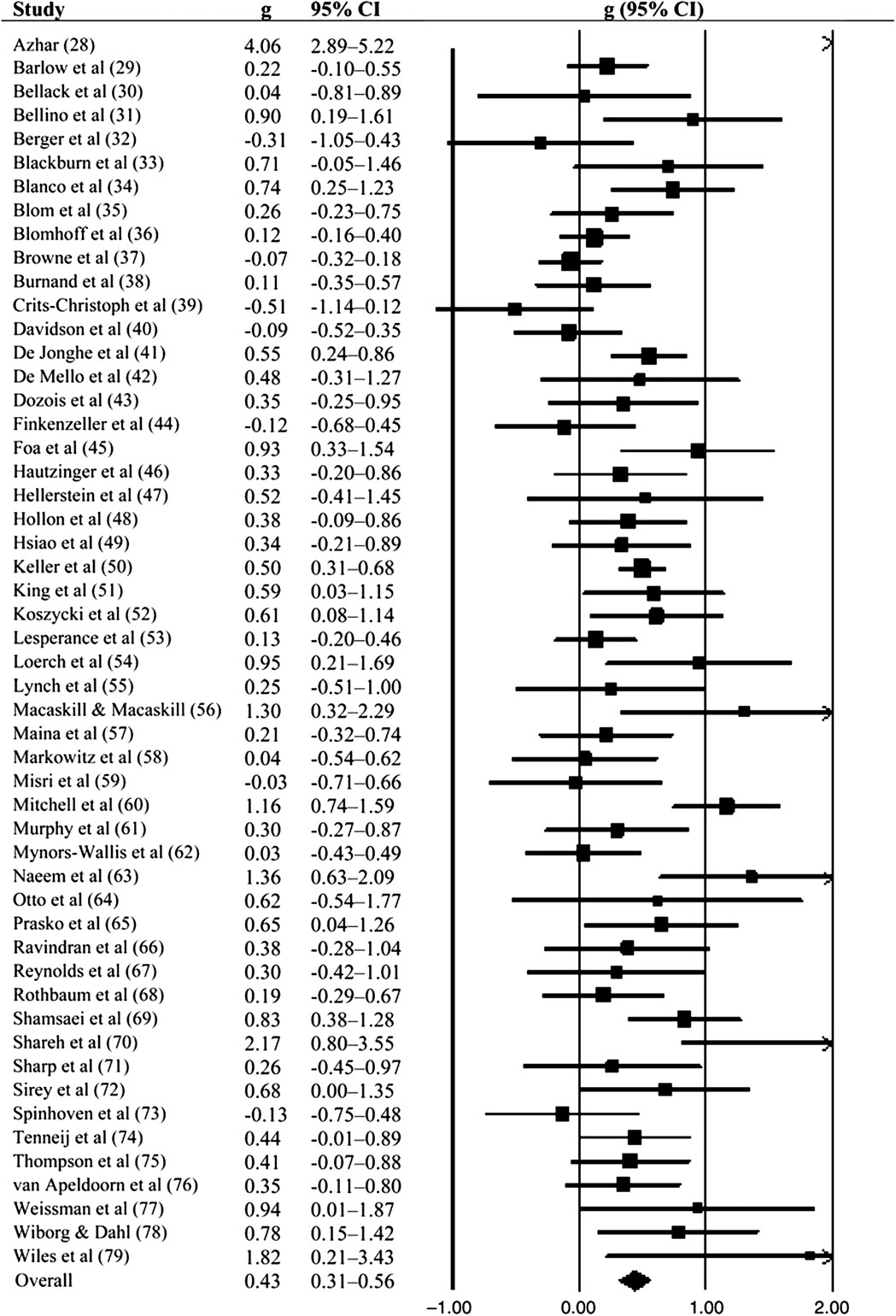

2 = 48). The results of these analyses are reported in

Table 2. A forest plot of the studies and their effect sizes is given in

Figure 2.

For specific disorders, we found evidence that combined treatment was more effective than pharmacotherapy alone in major depression (g = 0.43; 95% CI: 0.29-0.57; NNT = 4.20), panic disorder (g = 0.54; 95% CI: 0.25-0.82; NNT = 3.36), and OCD (g = 0.70; 95% CI: 0.14-1.25; NNT = 2.63). We also found some indication that combined treatment may be more effective than pharmacotherapy in SAD (g = 0.32; 95% CI: −0.01-0.71; NNT = 5.56), although this was not significant (p<0.1). Insufficient evidence was found for dysthymia, PTSD, and GAD.

Inspection of the funnel plot and Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure pointed at some risk of publication bias. After adjustment for possible publication bias, the overall mean effect size was reduced from g = 0.43 (NNT = 4.20) to g = 0.29 (95% CI: 0.15-0.43; NNT = 6.17; number of imputed studies: 10). Egger’s test of the intercept also indicated significant publication bias (intercept: 1.33; 95% CI: 0.24-2.42; p<0.01).

We found no indication that combined treatment resulted in lower dropout from treatment than pharmacotherapy alone. The RR of dropping out of treatment, in the 35 studies in which dropout was reported, was RR = 0.99 (95% CI: 0.95-1.03; I2 = 24; 95% CI: 0-50).

Subgroup analyses indicated no significant differences between the effects sizes of depressive and anxiety disorders, between the different depressive disorders (while excluding anxiety disorders), and between the different anxiety disorders (while excluding depressive disorders) (

Table 2). We also found no indication that the effect sizes differed according to the type of medication (SSRI; TCA; other or protocolized), target group (adults in general or more specific target group), psychotherapy treatment format (individual or group), type of therapy (CBT; IPT; other), number of treatment sessions (5-9; 10-12; 13-18; >19); and quality of the studies (meeting 3 or 4 criteria versus less than 3 criteria). We did find a trend (p<0.1) indicating that the effect size may be higher in clinical samples (g = 0.49) compared with samples that included patients recruited from the community (g = 0.27).

We examined whether baseline severity was associated with outcome in the 20 studies examining depressive disorders. Mean baseline severity according to the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) was moderate in 16 of the 20 studies (score 18-24), severe in three studies (score >24), and mild in one study (score <18) (

80). In a meta-regression analysis, we did not find any indication that the effect size of difference between pharmacotherapy and combined treatment was associated with baseline severity of depression (slope: 0.007; 95% CI: −0.022-0.038; p = 0.63).

Combined Treatment Versus Placebo

In 11 of the 53 studies, the combined treatment could be compared to a pill placebo control group. All of these studies also included a psychotherapy-only condition (with or without a pill placebo), as well as a pharmacotherapy-only condition. This allowed us to calculate the effect sizes indicating the difference between pharmacotherapy and placebo, psychotherapy (with or without a pill placebo) and placebo, as well as between combined treatment and placebo. With these effect sizes we could estimate the contribution of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy to the effects of combined treatment.

The results of the analyses are presented in

Table 3. The effects of combined treatment compared with placebo are large (g = 0.74; 95% CI: 0.48-1.01; NNT = 2.50), with moderate to high heterogeneity (I

2 = 65; 95% CI: 33-82). In these 11 studies, the effect size of pharmacotherapy compared with placebo was g = 0.35 (95% CI:0.21-0.49) and that of psychotherapy compared with placebo was g = 0.37 (95% CI: 0.11-0.64). This suggests that the effects of psychotherapy and those of pharmacotherapy are largely independent of each other, and each add about 50% to the overall effects of combined treatment. The independence of the effects of the two kinds of treatments is further supported by the effect sizes of pharmacotherapy versus combined treatment (g = 0.37 in this sample), and those of psychotherapy versus combined treatment (g = 0.38).

Long-term Differences Between Pharmacotherapy and Combined Treatment

Long-term differences between pharmacotherapy and combined treatment were reported in 19 studies, with follow-up periods varying from 3 to 24 months. Because the way positive outcomes were defined differed from study to study, we have reported the definition of a positive outcome at each of the follow-up points in

Table 4.

The RR of having a positive outcome for all follow-up periods together was 1.48 (95% CI: 1.23-1.78; NNT = 4.29), and ranged from RR = 1.40 to 1.51 (NNTs: 3.41 to 6.90) for the four follow-up periods we distinguished. In each of the four follow-up periods, combined treatment was significantly more effective than pharmacotherapy alone (

Table 5).

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we found clear evidence that combined treatment with psychotherapy and antidepressant medication is more effective than treatment with antidepressant medication alone. This difference was significant for major depression, panic disorder, and OCD. A trend indicated possible superior effects in SAD. We did not find sufficient evidence for a significant difference in dysthymia, PTSD and GAD, but this could be due to the small number of studies and associated lack of statistical power for these disorders. The superior effects of combined treatment remained significant at one to two-year follow-up.

We found that the superior effects of combined treatment may have been overestimated by publication bias, which is in line with earlier research on pharmacotherapy (

81) as well as psychotherapy (

82), showing evidence of publication bias in both fields. However, even after adjusting for publication bias, the superiority of combined treatment was still statistically significant.

We also found some indications that the difference between pharmacotherapy and combined treatment was especially high in clinical samples compared with samples that were (in part) recruited from the community. Although this difference was only marginally significant (p<0.1), it does suggest that patients actively seeking treatment may benefit more from combined treatment than people who are recruited from the community.

Research up to now has not been able to answer the question of how large the effects of combined treatment are compared with pill placebo only. We found indications that the effects of combined treatment compared with placebo only were about twice as large as those of pharmacotherapy compared with placebo only.

Until now it has not been established well whether the effects of pharmacotherapy and those of psychotherapy are complementary to each other, whether they have effects independent from each other, or whether combined treatments lead to higher effects than the sum of the two treatments alone (

83,

84). The present study indicates that the effects of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy may be largely independent from each other and additive, not interfering with each other, and both contribute about equally to the effects of combined treatment.

From a clinical point of view, this paper suggests that combined treatment should be used in more patients than is currently done in clinical practice. Most patients receive either pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy (

16,

17), and only a minority receives combined therapy. Combined treatment is especially given to more severe and chronic cases. Our data suggest that the superior effects of combined treatment are not associated with baseline severity, at least in depression. Because the effects of the two treatments seem to be largely independent from each other, combined treatment may also be beneficial in less severe cases.

This study has some limitations. First, it is not possible to blind comparisons of pharmacotherapy to combined treatment and this may have introduced a bias in the outcomes. Second, because patients refusing antidepressants may not have been willing to be enrolled in trials, there may have been a sampling bias that could limit the generalizability of these findings. Third, we found considerable levels of heterogeneity among the studies, which could not fully be explained by moderator analyses. Another limitation was the relatively small number of included studies for some disorders. A final limitation is that we considered psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy as monolithic treatments, while in fact several different treatments were used in the included studies.

In sum, the present study found superior effects of combined treatment over pharmacotherapy alone, which are significant and relevant up to two years after treatment. These results thus support the use of combined treatment for common mental disorders rather than monotherapy with psychotropic medication without psychotherapy.