Epidemiology

Both Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies are age-related diseases, although onset before age 65 years is not uncommon and both diseases are more common in men than in women.

The point-prevalence of dementia is roughly 25% in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

6 The risk of dementia increases with duration of disease and reaches 50% 10 years after diagnosis.

7 Most patients who survive for more than 10 years will develop dementia.

8 The incidence of dementia is roughly 100 per 1000 person-years; however, it is much lower during the first years after diagnosis.

9,10 Increasing age is a risk factor for the development of dementia in patient’s with Parkinson’s disease, and thus the time to dementia decreases with increasing age at onset of Parkinson’s disease.

11There are fewer prevalence and incidence data for dementia with Lewy bodies. In a systematic review, estimates of the proportion of individuals with dementia with Lewy bodies ranged from 0 to 23% among people with dementia.

12 The mean prevalence of probable dementia with Lewy bodies was 4⋅2% in community-based studies and 7·5% in clinic-based studies. These values are probably underestimates, because the three studies that focused on identifying dementia with Lewy bodies and included a neurological examination showed higher proportions with the disease (16–24%).

12 In a population-based study, 7·6% of dementia cases were diagnosed as dementia with Lewy bodies.

13Dementia with Lewy bodies seems to be under-diagnosed in clinical practice.

14,15 Standardised scales focusing on the core features should be used. Furthermore, dopamine transporter imaging

16 and screening for rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder (RBD)

17 also increase the accuracy of diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Studies incorporating these methods suggest that 10–15% of people with dementia have dementia with Lewy bodies.

18,19In a study in the USA, the incidence of probable dementia with Lewy bodies was 3⋅5 per 100 000 person-years overall, and 31⋅6 per 100 000 person-years among people older than 65 years.

20 By contrast, a study in France estimated an incidence of 112 per 100 000 person-years in people aged 65 years and older.

21 One explanation for the difference is that the US study

20 included only patients who had a medical record diagnosis of a parkinsonian disorder, so people with mild or no parkinsonism would have been excluded. In the French study,

21 all participants were screened for symptoms of parkinsonism and cognitive impairment. In both studies, core features of dementia with Lewy bodies were sought retrospectively, based on records, and presence of RBD was not assessed systematically, probably leading to underdiagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies.

Pathogenesis

The hallmarks of Lewy body dementias are α-synuclein neuronal inclusions (Lewy bodies, and Lewy neurites), accompanied by neuronal loss. It is unclear whether Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites have a neuroprotective or neurotoxic role and to what extent they contribute to the clinical picture because some individuals have severe α-synuclein pathology at autopsy but no clinical symptoms of Lewy body dementia.

22 The underlying pathological cause of Lewy body dementias is probably multifactorial with factors that increase or decrease neural reserve also playing a part.

Braak and colleagues proposed a pathological staging of Parkinson’s disease (with or without dementia) with Lewy body pathology starting in the dorsal IX/X motor nucleus or adjoining intermediate reticular zone, and spreading rostrally in the brainstem (substantia nigra, basal ganglia) then to the limbic system and subsequently to the neocortex.

23 The mechanism of the spread of the disease process is unknown but evidence suggests that α-synuclein pathology can spread from cell to cell.

24 However, some patients with dementia with Lewy bodies do not follow the caudorostral progression, suggesting that alternative patterns of spread are possible.

22 The proposed Braak staging excluded patients with dementia with Lewy bodies, and so the applicability of caudorostral progression to the disease is not established.

The pathological substrate of dementia in Lewy body dementias is also debated. Dementia can be present in patients with pure cortical α-synuclein pathology but the underlying pathology is often mixed.

25,26 Cortical α-synuclein pathology is the strongest candidate substrate for Parkinson’s disease dementia, whereas amyloid β has a more prominent role in dementia with Lewy bodies.

27 However, even in Parkinson’s disease dementia, the presence of cortical tau-containing neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid β pathology leads to more advanced dementia, implying that the two pathologies work together.

28 There is little evidence that cerebrovascular pathology contributes substantially to cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease dementia. Vascular pathology often co-occurs with Alzheimer’s disease pathology in dementia with Lewy bodies but the contribution of cerebrovascular disease to dementia with Lewy bodies has not been established.

29Genetics

The genetics of dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson’s disease dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease overlap.

30 Most cases of Lewy body dementia seem to be sporadic but rare autosomal dominant inheritance has been reported, including mutations in the

SNCA and

LRRK2 genes.

31 The mutations can manifest as Parkinson’s disease, Parkinson’s disease dementia, or dementia with Lewy bodies, suggesting that the different clinical phenotypes are on a spectrum of one underlying genetic–pathological entity.

There is evidence of familial aggregation of dementia with Lewy bodies.

32 Several studies, including one large multicentre study,

33 have shown that mutations in

GBA are a significant risk factor for dementia with Lewy bodies and that carriers of mutations in

GBA develop dementia with Lewy bodies at an earlier age than non-carriers, although another large study

34 did not confirm this finding. That study showed an association between

SNCA and

SCARB2 and dementia with Lewy bodies.

The

APOE ε4 allele, a strong risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, is also over-represented in sporadic Lewy body dementias compared with controls, but it is less common than in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

35 The

APOE ε2 allele (the least common allele) might reduce the risk of developing dementia with Lewy bodies.

36Diagnosis and Clinical Symptoms

Panel 2 shows the diagnostic criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia. The biggest challenge in the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies is early diagnosis and differentiation from Alzheimer’s disease. In Parkinson’s disease dementia, the main challenge is prediction and timely identification of cognitive impairment in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

The current consortium criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies have been criticised for poor sensitivity. In 2861 patients from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, sensitivity of clinical diagnosis against autopsy was 32% and specificity was 95%.

38 The revised criteria of dementia with Lewy bodies

2 increased the proportion of cases fulfilling probable dementia with Lewy bodies criteria by 24%

39 by including suggestive features with additional diagnostic weighting. Diagnostic accuracy is higher when α-synuclein pathology is extensive, lower with increasing neuritic plaque pathology, and not affected by amyloid β load.

40Nevertheless, diagnostic accuracy is still only moderate in research and poor in clinical settings. Dementia with Lewy bodies is most often misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease. Including RBD as a core feature of disease improves sensitivity without sacrificing specificity.

17 Antipsychotic challenge should never be used for diagnosis because of associated morbidity. About half of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies react adversely to antipsychotics.

41 Fluctuating cognition is a particularly difficult clinical feature to elicit accurately. Fluctuation scales can be helpful but more studies of their reliability and validity are needed to standardise them.

42,43 In cases of dementia without parkinsonism, dementia with Lewy bodies is less likely to be considered, even though many patients with dementia with Lewy bodies never develop parkinsonism.

The sensitivity of the revised criteria could be improved by increasing the diagnostic weighting of some features, although this could lessen specificity. Upgrading visuospatial impairment to a core criterion could improve sensitivity because most patients with dementia with Lewy bodies have visuospatial impairment.

44 The specificity for dementia with Lewy bodies of visual hallucinations, parkinsonism, and fluctuating cognition is adequate only in mild-to-moderate dementia because these features are also common in late-stage Alzheimer’s disease.

38 Visual hallucinations are typically well formed and usually feature people, children, or animals. Low dopamine transporter uptake on single photon emission CT improves the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing dementia with Lewy bodies compared with Alzheimer’s disease, but does not distinguish other parkinsonian dementia syndromes such as progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration.

16,45The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

4 recognises dementia with Lewy bodies, termed “major neurocognitive disorder with Lewy bodies”. Criteria are similar to the consortium criteria but the suggestive feature of low dopamine transporter uptake has been omitted, which is likely to compromise sensitivity. Investigations are listed separately, termed “suggestive features”. However, they are subsumed under the heading “diagnostic markers” with unclear diagnostic weight.

The initial clinical presentations of Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies are distinct. Once dementia develops in Parkinson’s disease; no clinical or biological differences can reliably distinguish it from dementia with Lewy bodies.

Prodromal and Early Lewy Body Dementias

Cognitive impairment also occurs in patients with Parkinson’s disease without dementia, termed mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease (MCI-PD).

3 In cross-sectional samples, 20–25% of patients with Parkinson’s disease without dementia can be classified as MCI-PD,

46 and MCI-PD is present in 15–20% of patients at diagnosis. This syndrome is associated with some degree of functional impairment and is a risk factor for incipient dementia,

47,48 although this risk might depend on the profile of cognitive impairment.

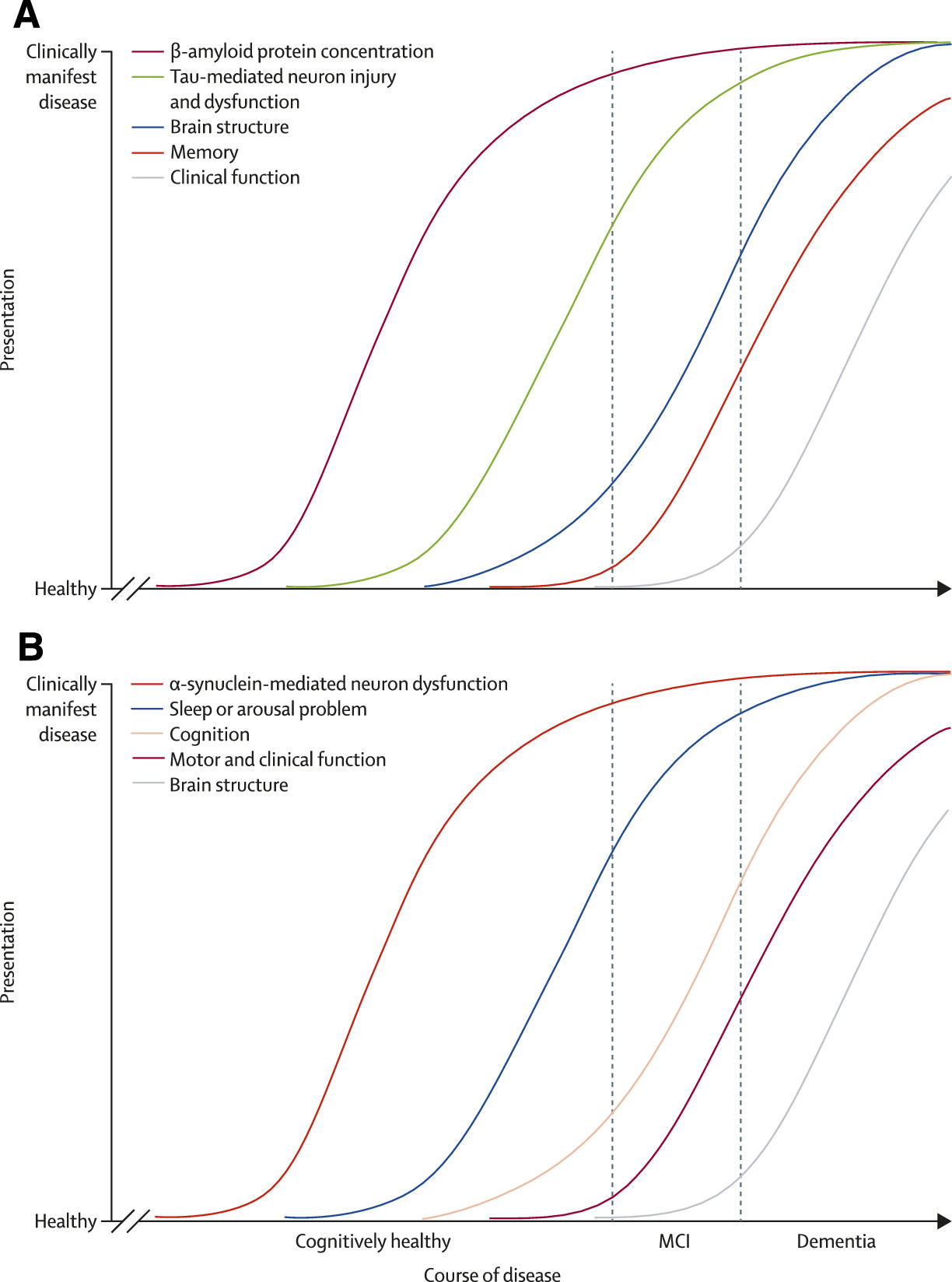

There is no consensus on how pre-dementia dementia with Lewy bodies should be defined. Given the complex clinical phenotype, the prodromal phase is probably heterogeneous.

49 Figure 1 shows a hypothetical model for the development of dementia with Lewy bodies. In patients with mild cognitive impairment, those with non-amnestic cognitive profile,

53 with parkinsonism or fluctuations,

54 with slowing on electroencephalography,

55 or problems with pentagon drawing

56 have an increased risk for developing dementia with Lewy bodies. In addition, patients with idiopathic RBD,

57 primary autonomic dysfunction,

58 and frequent delirium have increased risk of dementia with Lewy bodies.

59 Visual hallucinations in early or prodromal dementia are highly specific for a pathological diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies.

15 This finding is consistent with a study of patients with autopsy-confirmed dementia with Lewy bodies. Although few had visual hallucinations (22%), parkinsonism (26%), or both (13%) at the stage of mild dementia, visual hallucinations were the most specific feature differentiating dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer’s disease.

44Parkinsonism, visual hallucinations, olfactory dysfunction, constipation, increased salivation, and RBD are more common at the onset of dementia with Lewy bodies than of Alzheimer’s disease.

60,61 19 risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease were studied as potential risk factors for dementia with Lewy bodies.

62 A history of anxiety and depression was more common in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies than in cognitively healthy controls.

Neuropsychological Aspects of Lewy Body Dementias

Panel 3 shows the neuropsychological domains and tests pertinent to Lewy body dementias. Characteristically, visuospatial and executive deficits with fluctuations in cognition and arousal are present in Lewy body dementias. Visuospatial or constructional impairment is present in 74% of patients with early-stage pathologically confirmed dementia with Lewy bodies compared with 45% of those with Alzheimer’s disease,

44 and rarely in frontotemporal dementia.

77 The presence of early, severe visuospatial deficits in patients with suspected dementia with Lewy bodies predicts rapid decline and the development of visual hallucinations, and might identify patients whose clinical syndrome is due to Lewy bodies rather than Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

78 The cognitive profile of MCI-PD is heterogeneous, with many patients having executive, memory, or visuospatial impairments.

79 Executive dysfunction (deficits in selective attention, working memory, mental flexibility, planning, and reinforcement learning) can be prominent, and is primarily linked to nigrostriatal dopaminergic loss causing disruption of dorsolateral prefrontal–striatal circuitry.

80 Deficits on tests with a posterior cortical basis, specifically semantic fluency and figure copy, might herald subsequent dementia, whereas frontal-type executive deficits do not.

7 Once patients develop dementia, executive deficits are common and disabling, but of little use for differential diagnosis.

81,82Memory impairment does not preclude a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies: patients with pure Lewy body disease have similar free recall but better delayed recognition memory than those with pure Alzheimer’s disease or mixed pathology, suggesting impaired retrieval mechanisms.

83 Neocortical Lewy body pathology is related to yearly fluctuations on cognitive testing.

84 Mixed pathology complicates the neuropsychological profile, making it difficult to distinguish mixed Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies from pure Alzheimer’s disease.

Cerebrospinal Fluid and Electroencephalography Biomarkers

There is a drive to use biomarkers to enable preclinical, prodromal, and accurate clinical diagnosis and to monitor progression of disease and treatment effectiveness. Although Parkinson’s disease, Parkinson’s disease dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies are synucleino-pathies, authors of a systematic review

85 concluded that neither plasma nor cerebrospinal fluid α-synuclein are reliable biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease. However, the concentration of α-synuclein in cerebrospinal fluid could be useful in dementia with Lewy bodies. A meta-analysis of 2728 patients showed that the mean cerebrospinal fluid α-synuclein concentration was significantly lower in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies than in those with Alzheimer’s disease. No significant difference was recorded between dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease or other neurodegenerative disorders.

86 Findings of a large longitudinal study of patients with Parkinson’s disease

87 showed that lower baseline cerebrospinal fluid α-synuclein concentration predicted better preservation of cognitive function at follow-up.

Compared with Alzheimer’s disease, for which cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers have been shown to have good sensitivity and specificity, the evidence for Lewy body dementias is insufficient for amyloid β 40–42, amyloid β 38, and amyloid β 42:amyloid β 38 ratio. Although amyloid β 1–42 concentrations cannot distinguish dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer’s disease, the amount of concomitant Alzheimer’s pathology in dementia with Lewy bodies correlates with amyloid β 1–42 but not with total tau concentrations in neuropathologically defined patients.

88 Similarly, reduced amyloid β 1–42 concentrations also occur in Parkinson’s disease dementia

89 and MCI-PD, and in prospective studies, amyloid β 1–42 concentrations predicted future cognitive decline and early dementia.

90,91Additional markers might also have relevance. For example, plasma concentrations of epidermal growth factor can predict cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease.

92 Low background rhythm frequency ascertained with quantitative electroencephalogram is associated with cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease and can also predict the development of dementia in Parkinson’s disease.

93 Similarly, slow wave activity is common to all dementias but it is most prominent in dementia with Lewy bodies,

94 and characteristic abnormalities can even precede the appearance of distinctive clinical features.

95Imaging

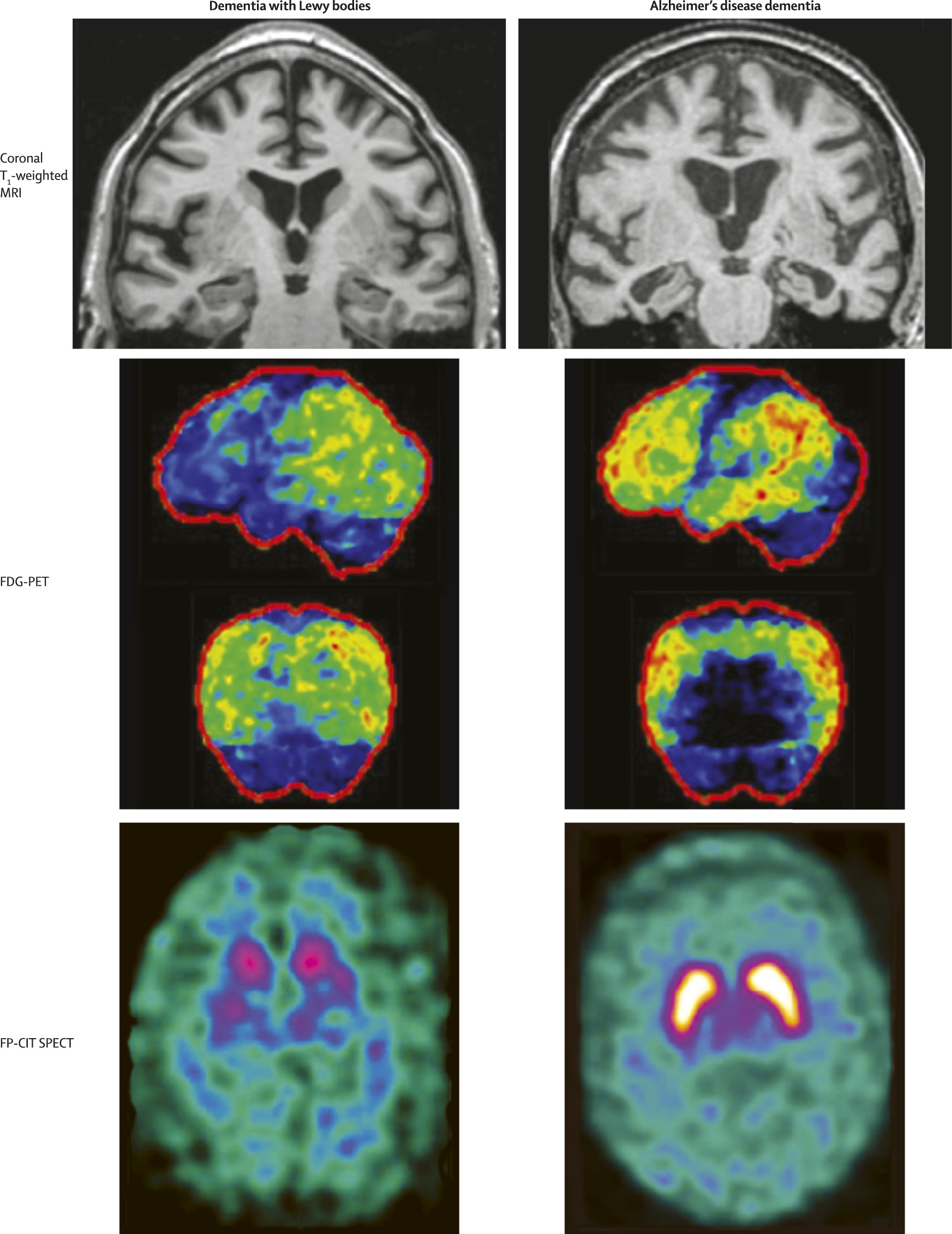

Most patients with suspected dementia with Lewy bodies or Parkinson’s disease dementia will have a CT or MRI scan as part of basic clinical investigations. But the number of imaging techniques that can be used in the diagnostic assessment is growing.

In both Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies, a structural MRI has little value for the differential diagnosis from other dementias (

table 1). Other techniques include perfusion single photon emission CT and metabolic PET. Occipital hypometabolism is the most distinct finding in dementia with Lewy bodies compared with Alzheimer’s disease and healthy controls (both Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies show temporoparietal hypometabolism). Reduced occipital metabolism and perfusion are supportive features in the 2005 consensus criteria

2 for dementia with Lewy bodies, and occipital hypometabolism can distinguish dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer’s disease and healthy controls with high sensitivity and specificity.

103,104 Kantarci and colleagues

105 reported an association between occipital hypometabolism and the frequency of visual hallucinations. However, occipital hypometabolism is not always present in neuropathologically confirmed disease.

106 The posterior cingulate island sign, which reflects relatively preserved metabolism in the posterior cingulate region, is sensitive and specific for dementia with Lewy bodies.

107,108 Patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia also have hypometabolism in frontal, parietal, and occipital regions.

109123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy, a marker of postganglionic cardiac sympathetic innervation, shows promise as a biomarker of dementia with Lewy bodies. A meta-analysis

110 of 46 studies involving 2680 patients with neuropsychiatric and movement disorders showed that it reliably distinguished between patients with Lewy body dementias and patients with Alzheimer’s disease. A large Japanese multicentre study

111 using consensus diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies showed good sensitivity and specificity, similar to dopamine transporter imaging. Patients with substantial cardiac disease or poorly controlled diabetes were excluded. Clinicians should be aware that the presence of cardiac disease and diabetes needs to be taken into consideration when

123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy is done to avoid false positives.

Low dopamine transporter uptake in basal ganglia is a suggestive feature in the consensus criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies. The ligand most often studied is

123I-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl)-N-(3-fluoropropyl) nortropane (FP-CIT) in single photon emission CT. It has high sensitivity and specificity for dementia with Lewy bodies in both clinically (consensus panel) and pathologically diagnosed cases, and possible dementia with Lewy bodies.

16,112–114 A meta-analysis

115 of four studies with 419 patients showed high diagnostic accuracy of FP-CIT, and a Cochrane review

116 concluded that semiquantitative analysis of scans seemed to be more accurate than visual rating. However, some caution is needed. Although a normal FP-CIT scan does exclude a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease dementia, it does not exclude a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. 3–9% of patients who have dementia with Lewy bodies have cortical and limbic pathology without nigrostriatal pathology (false negative). Rarely, diagnoses will be false positive. About a third of patients with frontotemporal dementia have an abnormal (positive) FP-CIT scan and could therefore be mistaken for dementia with Lewy bodies.

117 Also, most patients with progressive supranuclear palsy and cortico-basal degeneration have abnormal (positive) FP-CIT uptake. However, it should be possible to separate dementia with Lewy bodies from frontotemporal dementia, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration on clinical grounds. Therefore, FP-CIT imaging might be particularly useful when the typical clinical features of frontotemporal dementia, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration are absent and the primary diagnostic consideration is dementia with Lewy bodies or Alzheimer’s disease.

Figure 2 shows examples of findings on MRI, FDG-PET, and FP-CIT single photon emission CT.

In the past 5 years, amyloid imaging studies have proliferated. Most used

11C-Pittsburgh compound B but

18F-labelled ligands are also available. Overall, patients with dementia with Lewy bodies have higher amyloid retention than do patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia and healthy controls but lower than patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

102 The presence of amyloid deposition has little value in separating dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer’s disease,

118 but increased amyloid load is associated with the development of dementia in Parkinson’s disease and with faster cognitive decline in dementia with Lewy bodies.

101 Testing for amyloid load in Lewy body dementias might be important when treatments that target specific pathology become available.

RBD

RBD is a parasomnia characterised by abnormal vocalisations, motor behaviour, and dream mentation, in which patients seem to act out their dreams by yelling, screaming, flailing limbs, punching, and kicking.

119,120 Such dreams typically involve a perceived attacker such as a human, animal, or insect, towards which the vocalisations and limb movements are directed. While a formal diagnosis needs confirmation of increased electromyographic tone with or without dream enactment behaviour on polysomnography, a strong suspicion of RBD can be ascertained by history, and several simple and accurate questionnaires are available.

121RBD is relevant to Lewy body disease for many reasons. It is strongly associated with α-synucleinopathies. The presence of RBD increases the diagnostic likelihood of synucleinopathy-spectrum disorders compared with Alzheimer’s disease and the primary tauopathies.

122 Prospective analyses have shown that 70–90% of patients with RBD develop dementia (usually dementia with Lewy bodies) or parkinsonism (usually Parkinson’s disease) within 15 years.

123–125 RBD arises from pathology in the brainstem circuitry involved in the control of rapid eye movement sleep. Although the pathophysiology of human RBD remains unclear, degeneration of the sub-coeruleus region or magnocellular reticular formation (or both) has been proposed to be responsible. These regions are affected by Lewy body disease and, according to the Braak staging, are involved earlier than the substantia nigra, limbic system, and neocortex.

126 This pattern of development of pathology would explain why RBD often precedes the typical motor, cognitive, and neuropsychiatric manifestations of Lewy body dementias by years or decades.

127,128Management

Management of patients with Lewy body dementias is challenging. There are no disease-modifying drugs so treatment is directed towards symptoms; however, very few randomised controlled trials of treatments exist. The range of problematic manifestations of Lewy body dementias, along with high sensitivity to drug-induced adverse events and the likelihood that some drugs might improve one symptom but worsen others, contribute to the difficulties of management. One needs to be extremely cautious with all forms of treatment for patients with Lewy body dementias. Despite these challenges, comprehensive management is feasible by identifying and prioritising target features and then applying evidence-based measures (

table 2).

129,131–133 In general, careful dosing and monitoring schedules are recommended.

The acetylcholinesterase inhibitor rivastigmine moderately benefits cognition, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and activities of daily living in patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia,

134 whereas donepezil showed mixed results in a large randomised controlled trial.

135 In dementia with Lewy bodies, rivastigmine improved attention and memory in a small study,

136 but did not affect Mini-Mental State Examination score or clinical impression. More convincing findings were reported in two large placebo-controlled studies,

137,138 which showed efficacy both on Mini-Mental State Examination score and clinical global impression of change after 12 weeks on 5 mg and 10 mg donepezil. These improvements were maintained for 52 weeks in both studies.

139,140 A Cochrane review

132 concluded that acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are beneficial for patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia. Gastrointestinal side-effects were common, but no overall worsening of motor symptoms was noted. Thus, we recommend that acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, in particular rivastigmine and donepezil in standard doses, are used in Lewy body dementias.

132Some

141 but not all

142 studies have shown that memantine is modestly efficacious for overall impression of change, including for RBD, in patients with Lewy body dementias.

143 Mixed results have been reported in smaller studies, but a meta-analysis suggested that there is an overall improvement with memantine in Lewy body disorders.

144,145 Drugs with substantial anticholinergic properties are discouraged because of the risk of cognitive worsening and delirium.

Dopaminergic antiparkinsonian drugs can worsen visual hallucinations and other neuropsychiatric features, and thus reducing the dose of such drugs should be the first consideration. If this is not successful, there is good evidence that clozapine can reduce visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. However, severe dementia is a common exclusion criterion in these studies

146 and only two studies

147,148 included patients with Parkinson’s disease and cognitive impairment but did not report data on the subgroup of patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia. The use of clozapine is limited because of its potential to induce agranulocytosis and the necessity for regular blood monitoring.

Several open-label studies have suggested that quetiapine is useful in dementia with Lewy bodies, but the only placebo-controlled study was small and reported no effect on agitation and psychosis.

149 There were no differences on a psychosis scale between quetiapine and placebo. The authors noted a large effect in the placebo group. Quetiapine was generally well tolerated.

Severe hypersensitivity reactions to antipsychotics with motor and cognitive worsening can occur in all forms of Lewy body dementias. In addition, strokes and other risks associated with the use of antipsychotics are more likely in elderly people with dementia. Although little positive evidence supports the use of antipsychotics for Lewy body dementias, many clinicians still use clozapine or quetiapine to treat psychotic symptoms. One promising new drug is pimavanserin, a selective serotonin 5-HT

2A inverse agonist, which significantly reduced psychotic symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease and was well tolerated in a randomised controlled trial.

150 Patients had a mean Mini-Mental State Examination score of 26, and thus most patients did not have dementia.

There is no systematic evidence that acetylcholinesterase inhibitors can improve visual hallucinations in patients with Parkinson’s disease, although they might be particularly effective in patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia who have visual hallucinations.

151 Incident visual hallucinations were less common in patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia receiving rivastigmine than in those receiving placebo,

134 suggesting a possible preventive effect. In dementia with Lewy bodies, rivastigmine reduced a summary scale of four neuropsychiatric symptoms (delusions, visual hallucination, apathy, and depression) by 30% compared with placebo.

136 These symptoms also improved with donepezil.

139 However, these studies did not specifically recruit patients with troublesome visual hallucinations; therefore, new, safe, and effective treatments for psychotic symptoms in patients with Lewy body dementias are needed. To conclude, for patients with visual hallucinations, if reducing dopaminergic drugs is not feasible, a practical option would be to start treatment with an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. If symptoms do not improve and treatment is strongly indicated, low doses of quetiapine or clozapine (12⋅5–50 mg per day) could be considered (while waiting for results of pimavanserin trials), but need to be carefully monitored and withdrawn if no response occurs or troublesome adverse events occur.

Antidepressants might improve depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease,

152 but people with dementia are usually excluded from trials and no evidence from randomised controlled trials is available in patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies. Antidepressants with prominent anticholinergic effects should be avoided. Psychostimulants (eg, methylphenidate, dextroamphetamine) and wake-promoting drugs (eg, modafinil, armodafinil) are used in clinical practice, but their effectiveness for apathy and drowsiness in patients with Lewy body dementia is unknown.

Although dopamine replacement treatment for Parkinson’s disease is well established, no trials have focused on Parkinson’s disease dementia, and it is generally considered to be less effective and have more side-effects in this group than in patients with Parkinson’s disease who do not have dementia. Similarly, no trials have been done in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies, but levodopa has been reported to improve parkinsonism in uncontrolled studies of dementia with Lewy bodies, although the response varies compared with that in Parkinson’s disease.

153 Even less is known about dopamine agonists. Side-effects (especially exacerbation of visual hallucinations or delusions) restrict their usefulness in dementia with Lewy bodies. Nevertheless, in patients with clinically significant parkinsonism, levodopa slowly titrated from 50 mg per day up to 300–600 mg per day should be considered, with close monitoring of side-effects.

Improving safety is the mainstay of management of RBD, including moving sharp objects away from the bed and placing a foam mattress on the floor next to the bed to minimise injury from falling or jumping off the bed. When necessary, low doses of clonazepam or melatonin, or both, can be effective.

154 Memantine or acetylcholinesterase inhibitors improve RBD in some cases.

143 Hypersomnia is also common in patients with Lewy body dementias, due to varying degrees of nocturnal sleep fragmentation, sleep apnoea, periodic limb movements and associated arousals, and alterations in the intrinsic sleep–wake physiology. Treatment of these causes of hypersomnia should be considered, including nasal continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea and dopaminergic or other drugs for management of periodic limb movements. Wake-promoting drugs such as modafinil can be used for hypersomnia, but they have not been tested in randomised controlled trials. Insomnia can be treated with low doses of melatonin, sedatives or hypnotics, or mirtazapine (but mirtazapine can aggravate RBD).

For management of autonomic dysfunction, non-pharmacological treatments include increasing salt in the diet, use of compression stockings or an abdominal binder for orthostatic hypotension, elevation of the head of the bed during sleep to promote vasomotor tone while minimising supine hypertension, and increasing fluid intake and fibre in the diet for constipation. Dopaminergic drugs and atypical antipsychotics can exacerbate orthostatic hypotension; dose decreases are sometimes needed. Antihypertensive drugs can be withdrawn. Cholinergic stimulation in the gut from acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, which can cause diarrhoea in some patients, can ameliorate constipation in patients with Lewy body disease. Many drugs prescribed for urinary incontinence have anticholinergic activity and the potential benefit needs to be weighed against risk of cognitive worsening and delirium.

Despite no systematic evidence for the use of non-pharmacological strategies, cognitive behavioural therapy is effective for depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

155 However, cognitive impairment probably reduces feasibility of this treatment and is an exclusion criterion in many studies. Coping mechanisms for visual hallucinations might help some patients. Education and support to caregivers are important.