Clinical Presentation, Signs, and Symptoms

Individuals with anxiety disorders are excessively fearful, anxious, or avoidant of perceived threats in the environment (eg, social situations or unfamiliar locations) or internal to oneself (eg, unusual bodily sensations). The response is out of proportion to the actual risk or danger posed. Fear occurs as a result of perceived imminent threat whereas anxiety is a state of anticipation about perceived future threats.

3 Panic attacks feature prominently as a particular type of fear response. Avoidance behaviours range from refusal to enter situations to subtle reliance on objects or people to cope.

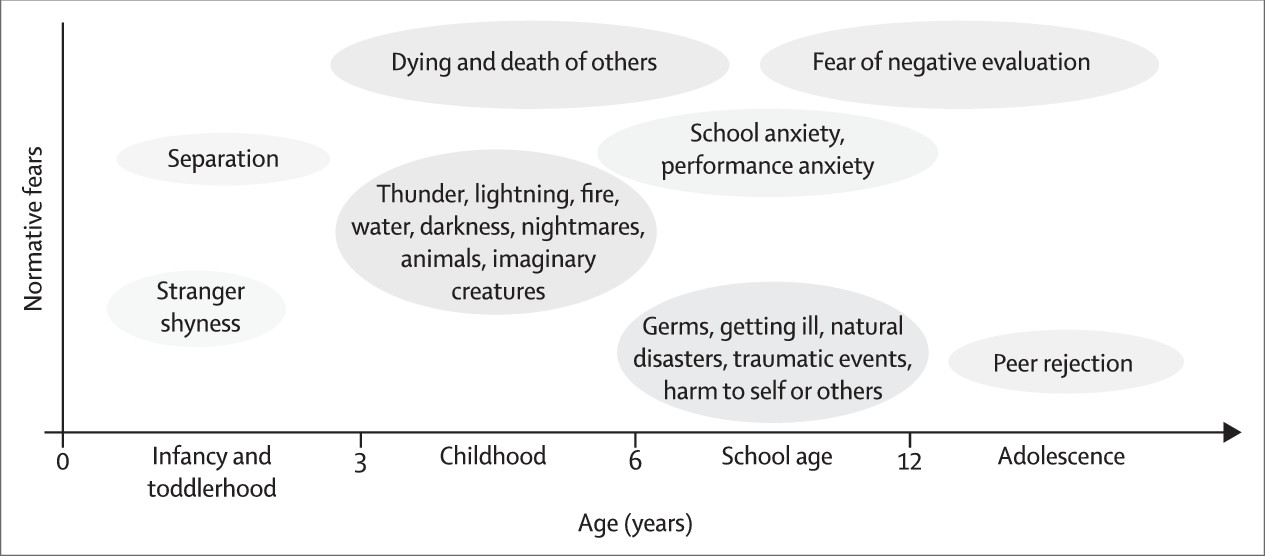

Fear and anxiety are common in everyday life. To be diagnosed as an anxiety disorder, the fear and anxiety are marked (excessive or out of proportion to the actual threat posed), persistent, and associated with impairments in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Most fears throughout childhood and adolescence are developmentally normative (

figure)—only around 23% represent anxiety disorders.

5 Throughout adulthood, transient fear or anxiety can emerge around periods of life stress, but these symptoms are not diagnosed as anxiety disorders unless they persist (eg, for at least 6 months) and interfere with functioning.

The panel summarises the essential symptoms for the major anxiety disorders as specified in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

6 (DSM-5) and the tenth edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10).

7 The gist of each disorder is highly similar between DSM-5 and ICD-10, and in both, the fear or anxiety is marked, persistent, and impairing. Revision to ICD is underway, with ICD-11 expected to be published in 2018. Early indications are that clinical use will be emphasised in ICD-11.

8Although categorical diagnostic criteria can be clinically useful, anxiety is a dimensional construct, and the distinction between what is normal and abnormal rests on clinical judgments of severity, frequency of occurrence, persistence over time, and degree of distress and impairment in functioning.

Moreover, the anxiety disorders can be thought of as sharing common dimensions, such as acute fear, anticipatory anxiety, or sustained threat response, which form part of the negative valence construct outlined in the Research Domain Criteria initiative from the National Institute of Mental Health.

9,10 Such dimensions could explain the common comorbidity between anxiety disorders.

Differential Diagnosis

Although the various anxiety disorders share many clinical features (hence their grouping together), they can be distinguished from one another by their defining diagnostic characteristics. Different anxiety disorders can have identical or very similar behavioural manifestations (eg, avoidance), but enquiries about associated beliefs (ie, cognitions) usually allow discernment of the prevailing diagnosis. For example, an individual might describe fear of being in crowds, such as shopping centres. The underlying anxiety disorder could be agoraphobia (if the fear is of incapacitation or being unable to escape from such situations), social anxiety disorder (if the fear is of scrutiny and assessment by others in such situations), panic disorder (if the fear is of panic attacks), separation anxiety disorder (if the fear is of separation from an attachment figure), or specific phobia (eg, if the fear is of lifts).

However, inquiry into cognitive ideation might not be sufficient. Selective mutism, for example, can be very difficult to distinguish from social anxiety disorder. This overlap is an artifact of the diagnostic criteria, in which most children with selective mutism are acknowledged to also meet criteria for social anxiety disorder (at least in DSM-5).

6 Many experts see these conditions as the same underlying disorder, although the DSM-5 Anxiety Work Group thought that evidence was insufficient to unify the diagnoses.

11 Another example is fear of driving, for which the differential diagnosis includes agoraphobia (defined by the presence of several characteristic fears, one of which could be driving in some situations) and specific phobia (defined by the presence of a specific fear, which could be driving in general or driving on bridges specifically). Inevitably, such diagnostic conundrums are resolved over time as the clinician and patient become more cognisant of the motivations for (if not always the origins behind) the fears and related behaviours.

Importantly, panic attacks—although prototypical of panic disorder when they occur unexpectedly or without an obvious cue or trigger—occur in association with many other mental disorders. Individuals with social anxiety disorder might have panic attacks in anticipation of imminent exposure to a horde of strangers at a business event. Those with post-traumatic stress disorder might have panic attacks when exposed to reminders of their traumatic events. Patients with depression can have occasional panic attacks, which might connote a severe and difficult course of depressive illness.

12Many mental and physical health conditions have symptoms that overlap with and yet can be differentiated from anxiety disorders. Major depression and bipolar disorder are frequently accompanied by anxiety symptoms: depression with anxiety symptoms can be considered the modal presentation of such disorders in most clinical settings.

13 Although depressive disorders are typified by features such as anhedonia and hopelessness, which are not inherent in anxiety disorders, many patients with depression are also anxious. This dual presentation of anxiety plus depression might reflect true comorbidity (eg, co-occurring major depression and generalised anxiety disorder), so-called anxious depression (codified in DSM-5 as depression with anxious features, which might or might not reflect true comorbidity), or possibly even mixed anxiety and depressive disorder: a combination of subsyndromal depressive and anxiety symptoms.

7,14 Anxiety symptoms are myriad in association with alcohol and other substance-use disorders, during both use (eg, cocaine) and withdrawal (eg, alcohol;

table 1).

Epidemiology

Anxiety disorders as a group are the most common class of mental disorders.

1 In a systematic review

2 of prevalence studies across 44 countries, the global prevalence of anxiety disorders was estimated at 7·3% (95% CI 4·8–10·9), suggesting that one in 14 people around the world at any given time has an anxiety disorder. Furthermore, roughly one in nine (11·6% [95% CI 7·6–17·7]) will have an anxiety disorder in a given year. Worldwide, women are twice as likely as men are to have an anxiety disorder; adults aged 55 years or older are 20% less likely to have an anxiety disorder than are those aged 35–54 years. Notably, prevalence estimates for anxiety disorders vary across countries, with 12 month prevalence ranging from 2·4% in Italy to 29·8% in Mexico. Controlling for variations in characterisation and methods, prevalence in the USA and European countries tends to be higher than that in other areas of the world. Although no data exist for prevalence of anxiety disorders across generations, some evidence suggests increasing endorsement of anxiety symptoms,

15 which could reflect increased exposure to threat-relevant information (eg, via the internet) or improved methods of detection.

Findings from epidemiological surveys from various countries consistently show specific phobia to be the most common anxiety disorder, with lifetime estimates in the range of 6–12%.

2 Most individuals have more than one specific phobia, and multiple specific phobias are associated with increased severity and impairment.

16 The next most common is social anxiety disorder, with a lifetime prevalence as high as 10%.

2 Social anxiety disorder tends to be higher in North America than in western Europe.

1 The discrepancy in prevalence between women and men is not as great for social anxiety disorder as it is for other anxiety disorders.

17 The other anxiety disorders are less common than is social anxiety disorder, with estimated lifetime prevalences of 3–5% for generalised anxiety disorder, 2–5% for panic disorder, 2–3% for separation anxiety disorder, and 2% for agoraphobia.

2 Among young age groups, spanning childhood and adolescence (typically to age 19 years), the most common anxiety disorders are specific phobias, social anxiety disorder, and separation anxiety disorder.

4 Selective mutism is rare (around 0·7–0·8%).

18Comorbidity among anxiety disorders is common, with as many as half of individuals with one anxiety disorder having another at some time in their lives, according to the National Comorbidity Survey–Replication (NCS-R) in the USA.

19 Anxiety disorders frequently co-occur with depression. The association with major depression is particularly strong for generalised anxiety disorder and moderately strong for panic disorder, agoraphobia, and social anxiety disorder.

19 Alcohol disorders

20 and other substance-use disorders are also comorbid with anxiety disorders, although to a lesser extent than they are with depression.

19 Comorbidity with personality disorders is also extensive.

21 High levels of comorbidity between anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive and stress-related disorders (eg, post-traumatic stress disorder) are recognised nosologically by being grouped together in the “Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders” section of ICD-10,

7 and by being placed in adjacent chapters in DSM-5.

According to the Global Burden of Disease study,

22 anxiety disorders are the sixth leading cause of disability in high-income and low-income countries, with the highest burden between age 15–34 years. Even subclinical forms of anxiety (eg, subthreshold panic disorder) are associated with distress and impairment.

23,24 Impairment and disability associated with anxiety disorders might be greater for women than for men.

25 Academic impairments are commonly noted in youth (aged 7–17 years) with anxiety disorders.

26In retrospective studies, most separation anxiety and specific phobias develop in childhood, most social anxiety disorder develops in adolescence or early adulthood, and age of onset for panic disorder, agoraphobia, and generalised anxiety disorder is typically later and with greater dispersion of distributions than in other forms of anxiety.

1 Prospective studies of children and adolescents often show even younger ages of onset of the disorder.

2 That said, cases of adult-onset separation anxiety disorder have been reported,

27,28 as has late-life onset of generalised anxiety disorder.

29 If untreated, anxiety disorders tend to be chronic, with a waxing and waning pattern of recurrence across the lifetime.

1,30Risk Factors and Pathophysiology

Childhood maltreatment (eg, childhood sexual abuse),

31 physical punishment in childhood,

32 parental history of mental disorders, low socioeconomic status,

20 and an overprotective or overly harsh parenting style

4 are all associated with increased risk of anxiety disorders. These risk factors are non-specific—they increase risk for many mental disorders. By contrast, behavioural inhibition, a trait identifiable in early childhood (eg, a clinging to familiar others in the presence of strangers), is more specifically predictive of social anxiety disorder (odds ratio 7·59, 95% CI 3·03–19·00).

32 Women are at an increased risk of each anxiety disorder

33 for reasons that remain unclear. Findings from genetic epidemiological studies

34 show moderate familial aggregation for anxiety disorders, with heritability estimates in the range of 30–50%. Specific genetic susceptibility loci have yet to be convincingly replicated, although several candidates, including

CAMKMT, which encodes the CAMKMT on chromosome band 2p21, have been identified in a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of anxiety disorders.

35 A meta-analysis

36 of genome-wide association studies for neuroticism, which is substantially more common among people with anxiety or depression than in those without anxiety or depression, has shown that a single-nucleotide polymorphism in the

MAGI1 gene is a new locus for that trait. Investigators of future studies should examine single-nucleotide polymorphisms in

MAGI1 and in other newly discovered neuroticism loci

37 for their possible association with anxiety disorders.

The pathophysiology of anxiety disorders is poorly understood. Overgeneralisation of conditioned fear

38,39 and deficits in the extinction of conditioned fear

40 are hypothesised to contribute to the development of anxiety disorders. Brain imaging studies,

41–44 in which use of functional MRI is increasingly prominent, tend to suggest overactivity in limbic regions, such as the amygdala and insula, during the processing of emotional stimuli, and aberrant functional connectivity between these regions and each other and other presumptively inhibitory regions in the brain, such as the medial prefrontal cortex.

Tools and Methods for Diagnosis

Aside from medical testing for differential diagnosis, anxiety disorders in adults are typically diagnosed on the basis of structured clinical interviews, such as WHO’s Composite International Diagnostic Interview,

45 the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview,

46 and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5.

46 Diagnosis of anxiety disorders in young children is usually dependent on interviews with parents, caregivers, or teachers.

Anxiety disorders can be screened for with self-report questionnaires, such as the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7)

47 or the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale.

48 Several self-report scales map onto the diagnostic criteria and can provide provisional diagnosis—for example, the child and parent versions of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale

49,50 and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire IV for adults.

51 Other self-report scales measure important dimensions that are useful for assessment of severity and treatment-related changes. Examples include the number of agoraphobic situations that are avoided,

52 fear of situations and activities associated with panic attacks,

53 belief that symptoms of anxiety are harmful,

54 intensity of fear, avoidance and physiological arousal in social situations,

55 excessive and uncontrollable worry (a pivotal feature of generalised anxiety disorder),

56 and fear and avoidance of a large array of objects and situations relevant to specific phobia.

57Psychological Treatment

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the most empirically supported psychological treatment for youth and adult anxiety disorders. CBT is a short-term (eg, 10–20 weeks), goal-oriented, skills-based treatment that reduces anxiety-driven biases to interpret ambiguous stimuli as threatening, replaces avoidant and safety-seeking behaviours with approach and coping behaviours, and reduces excessive autonomic arousal through strategies such as relaxation or breathing retraining.

58 Several meta-analyses

59–64 show that CBT is an efficacious treatment for anxiety disorders, with effect sizes largest when it is compared with no treatment (

table 2). Effect sizes relative to psychological placebo and active psychological treatment are smaller than are those relative to no treatment. For the comparison between CBT and active psychological treatment, effect sizes do not significantly favour CBT in late-life and childhood anxiety.

Computer-assisted and internet-based treatments (e-interventions) have grown rapidly over the past decade, and can provide care to those who do not otherwise have access (eg, people who live in rural locations or areas with long waiting lists for CBT, people with economic limitations) or prefer anonymity.

65 Most e-interventions for anxiety disorders are CBT. Findings from meta-analyses substantiate the efficacy of e-interventions for adult and youth anxiety, at least in comparison with no treatment, although study quality is often judged to be low to moderately low (

table 2). Although CBT seems to be effective for youth anxiety, very few randomised controlled trials have been done to assess CBT for selective mutism.

66–67 The added benefit of inclusion of family members or parents in the treatment of older children (eg, aged 8–13 years) with anxiety disorders remains uncertain.

61–68 For very young children (eg, aged 5–7 years), parent training alone could be sufficient.

69Findings from a review

70 of 87 studies of CBT for anxiety disorders in adults showed proportions of patients who achieved symptom reduction to within normative levels) of 52·7% for specific phobia, 45·3% for social anxiety disorder, 53·2% for panic disorder or agoraphobia, and 47·0% for generalised anxiety disorder. CBT also results in moderate improvement in measures of quality of life compared with waiting-list, placebo, and active treatments (n=21; Hedges’ g 0·56, 95% CI 0·32–0·80).

71 In children, evidence-based treatments (ie, CBT or drugs) are associated with improvements in academic performance as perceived by parents.

26Early prevention promises to be very cost-effective by offsetting functional impairments associated with anxiety disorders

22 and other mental disorders, such as depression and substance-use disorders.

1,72 CBT interventions for youth who are at risk of anxiety disorders by virtue of factors such as parental anxiety or a behaviourally inhibited temperament reduce symptoms of anxiety and risk of onset of anxiety disorder.

73–75The evidence base for other psychological treatments is much less robust than that for CBT. Interest in training programmes for cognitive bias modification (eg, training attentional bias away from threat-relevant stimuli or training neutral or positive interpretations of ambiguous material) has been challenged by small effect sizes in terms of anxiety symptoms (eg, Hedges’ g 0·13 to 0·27) in clinical samples.

76–78 Mindfulness and acceptance-based approaches are growing in popularity, but conclusions are hampered by the low quality of the studies and paucity of randomised controlled trials. Nonetheless, a meta-analysis

79 of six randomised controlled trials of mindfulness-based approaches compared with no treatment, placebo, or active controls showed a Hedges’ g of –083 (95% CI –1·62 to –0·04). Very few randomised controlled trials of psychodynamic approaches have been done. CBT was more effective than was interpersonal therapy (a short-term derivation of psychodynamic therapy) for panic disorder with agoraphobia.

80 In three studies with low risk of bias, alternative therapies had larger effect sizes for anxiety symptoms than did interpersonal therapy (Hedges’ g –0·33, 95% CI –0·59 to –0·06), although three studies have shown interpersonal therapy to be more effective for anxiety symptoms than inactive comparison conditions (0·89, 0·22 to 1·56) .

81 Panic-focused psychodynamic therapy fared well in comparison with CBT in another study,

70 although CBT showed the most consistent results across a complicated set of findings that differed by site.

Findings from a Cochrane review

82 showed that aerobic exercise results in small improvement in symptoms of anxiety in children and adolescents who were not in treatment, but no studies of the effects on anxiety for children who were in treatment were found. For adults with anxiety disorders, the evidence does not support the efficacy of aerobic exercise compared with control conditions, although research remains scarce.

83Pharmacological Treatment

Drug therapies are available for all of the anxiety disorders.

84 Reduction in anxiety symptoms with drugs yields meaningful improvement in health-related quality of life and reduced disability.

85 Antidepressants are the first-line pharmacological treatment for most anxiety disorders (with the exception of specific phobias), on the basis of evidence of efficacy from randomised controlled trials, overall safety, and absence of misuse potential.

86 Additionally, because many patients with anxiety disorders also have depression,

72 use of antidepressants enables joint treatment. Among the antidepressants, the most commonly used are the selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-noradrenaline-reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

Whereas not all the SSRIs and SNRIs have regulatory approval from the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency for each anxiety disorder, one or more drugs from within each of these categories is effective for anxiety disorders in adults, adolescents, and, to a lesser extent in terms of the body of evidence, children.

87 Importantly, no evidence exists that any SSRI or SNRI is better than is any other in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Accordingly, selection of a particular drug is based on previous response (if previously treated successfully), the patient’s preference (which might be based on what they hear from family, friends, and the media), and the physician’s familiarity with the drug.

Non-psychiatrists need not be familiar with every antidepressant. Rather, familiarity with a few (eg, one SSRI and one SNRI), being comfortable with their dosing, and anticipating and managing their side-effects will stand most doctors in good stead in the treatment of anxiety (and major depressive) disorders.

The main difference between treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders is the starting dose. Patients with anxiety tend to be sensitive to most drug side-effects, so the recommended starting dose is half that recommended for depression. That dose should be maintained for 1–2 weeks and, if tolerated, subsequently doubled. Although the starting dose is lower than that for depression, the therapeutic dose for treatment of anxiety disorders is the same or higher. A common error is failure to titrate the antidepressant dose to reach a therapeutic dose. Underdosing is one of the contributors to the low proportion of guideline-concordant treatment of anxiety in primary care settings.

88 Once a good therapeutic response is achieved, that therapeutic dose should be maintained for 9–12 months,

84 after which a trial of discontinuation can be considered. Such discontinuation should be done slowly, at a rate of not more than a quarter of the dose each month, to minimise withdrawal symptoms (eg, nausea, dizziness, which occur commonly when stopping SSRIs and SNRIs) and reduce the likelihood of relapse.

Tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors have a historically strong evidence base for efficacy in many anxiety disorders, but their safety profiles now largely limit their use. Moclobemide, a reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase A that is not available in the USA, has proven efficacy in social anxiety disorder,

89 but has not been well studied for other anxiety disorders. Other antidepressant types have not been well studied or have not shown efficacy (eg, bupropion, vortioxetine) for most of the anxiety disorders, with the possible exception of vilazodone

90,91 and agomelatine

92 (both for generalised anxiety disorder), both of which have several randomised placebo-controlled trials to support their efficacy, although neither has regulatory approval for that indication. In the absence of data showing that vilazodone, agomelatine, or other new antidepressants are more efficacious or better tolerated than are marketed SSRIs or SNRIs for anxiety disorders, physicians are advised to prescribe SSRIs or SNRIs—particularly those available in generic (and therefore less expensive) form.

Controversy continues to surround use of benzodiazepines, which some experts think are over-used

93 and associated with potentially dangerous outcomes with regard to long-term risk of dementia.

94,95 Nonetheless, the efficacy of benzodiazepines for anxiety disorders is unequivocal and robust, both for short-term (eg, of new-onset panic disorder) and long-term (eg, of chronic generalised anxiety disorder) treatment.

96 Most expert guidelines continue to recommend use of benzodiazepines as second-line or third-line agents—either as monotherapy or in conjunction with antidepressants

97—for patients without current (or, ideally, past) alcohol or other substance-use disorders.

98–100Other drugs that could be used to treat anxiety disorders (often as an alternative to benzodiazepines) are gabapentin and pregabalin. Pregabalin has good evidence of efficacy in generalised anxiety disorder.

101 Atypical antipsychotics, such as quetiapine, also have good evidence in generalised anxiety disorder,

102 but their metabolic adverse effects should limit their use to patients refractory to other treatments.

103 Buspirone, an azapirone, non-benzodiazepine anxiolytic, is an effective treatment for generalised anxiety disorder, but probably for none of the other anxiety disorders.

86 β blockers, such as propranolol or atenolol, have some evidence of efficacy in acute prevention of performance anxiety (a circumscribed form of social anxiety disorder), but not in other anxiety disorders.

84 We are not aware of meta-analyses or systematic reviews in which the proportion of patients responding to different drugs for the different anxiety disorders are assessed.

Outstanding Research Questions

Treatment development is dependent on greater understanding of the neural, biological, cognitive, environmental, and other factors that contribute to anxiety disorders. With this knowledge in hand, treatments can be honed to target specific mechanisms and possibly different mechanisms for different individuals. As noted, fear generalisation is thought of as a hallmark feature of anxiety disorders, explaining why the same aversive experience can lead to pervasive and persistent fears of related stimuli in some individuals and yet have few effects in others. The role of the hippocampus in contextualisation of fear memories has been elucidated in rats.

115,116 However, how to enhance specific neuronal activity within the hippocampus to increase contextualisation and thereby reduce generalisation of initial fear acquisition,

117,118 or conversely to decrease contextualisation and thereby increase generalisation of fear extinction,

119 remains poorly understood.

Similarly, although advances have been made in understanding of the neural correlates of deficits in extinction learning,

40 understanding of the causal pathways remains poor. An association between early-life adversity and risk of anxiety disorders (and other mental disorders) has been established, but, again, the mechanisms through which early-life adversity confers such risk is unknown.

120 Large-scale longitudinal studies with granular measurement of adversity type and severity are needed to clarify these relations. Until that knowledge is gained, attempts at early prevention and intervention will remain blunted.

A substantial proportion of individuals relapse after psychological and pharmacological treatments and extant efforts at maintenance remain non-targeted (eg, continuation of drugs or CBT). Close assessment across multiple methods of response (eg, neural, immunological, behavioural, cognitive, self-reported) throughout and after treatment could detect early signs that predict relapse, which could suggest for whom maintenance strategies are most needed and the pathways through which relapse occurs, which, in turn, could highlight specific targets of intervention.

New drugs to treat anxiety disorders need to be developed. No mechanistically new drugs for anxiety disorders have reached the market in the past two decades. Much interest exists in use of pharmacological means to enhance retention of what is learned during psychotherapy, particularly exposure therapy. The best studied so far of these pharmacological augmenting drugs has been d-cycloserine, a partial glutamatergic NMDA agonist. However, a Cochrane review

121 of 21 studies showed no evidence of benefit of d-cycloserine augmentation of CBT for anxiety disorders, although the drug’s effects appear greatest when the effects of CBT are strongest, which could explain the limited effects when weak and strong CBT effects are combined in reviews.

122 Research is needed into other drugs that might enhance the acute and long-term effects of CBT. Another area of interest is methods for interruption of reconsolidation of fear memories to erase them. Early work has shown some promise, with both pharmacological (eg, propranolol) and behavioural methods for interruption of reconsolidation,

123 although the results are inconclusive and criticisms have arisen around the concept of disruption of memory consolidation.

124Additional research into new ways to enhance the effects of CBT is also needed. For example, one-session behavioural treatments are effective for specific phobias in children

125,126 and adults.

127 More research is needed to extend these benefits to patients with other forms of anxiety disorder. Another question pertains to the role of lay providers of CBT: some evidence suggests that non-professionals can deliver effective and cost-effective outcomes for several anxiety disorders.

128,129