Motivated by this theory, researchers have begun to develop methods (

7–

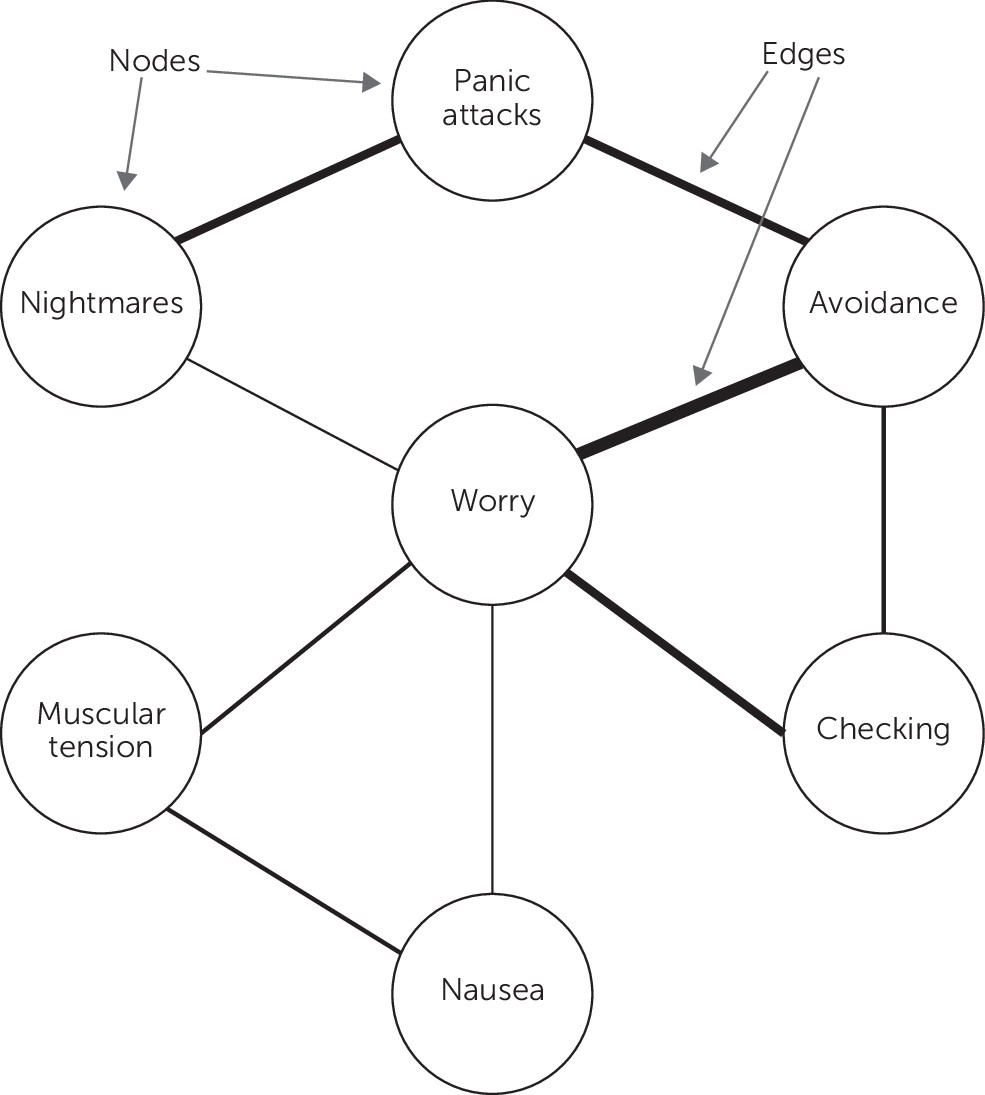

12) for investigating networks of symptoms and other psychological characteristics. In these network psychometric methods, the signs, symptoms, and other psychological problems are called “nodes,” and the relationships between these nodes are called “edges” (

Figure 1). Most commonly, edges represent statistical associations between two symptoms. The merits of various network psychometric methods, however, are distinct from the merits of network theory itself. No single statistical method is sufficiently informative to address the complexities of a psychological theory, which must be tested through multiple lenses. That said, network psychometric methods allow for a visualization of relationships that helps illustrate how mental disorders are conceptualized by network theory in its most basic form. With the aid of this visualization, we can review the implications of network theory for each of the three common assumptions that we have argued are prominent in psychiatric research.

Assumption 1: Mental Illnesses Exist Independently of Their Signs and Symptoms

Network theory posits that the set of psychological problems traditionally referred to as “mental illnesses” do not exist independently of their signs and symptoms. Instead, the relationship is mereological: whole to part. To illustrate, consider a school of fish. A school of fish does not exist independently from the fish. Whereas an independent disease entity (e.g., a cancerous tumor) can exist without the presence of any symptoms, a school of fish cannot exist without fish. In a similar way, network theory claims that mental disorders arise from a set of components (e.g., thoughts, emotions, behaviors, somatic experiences, and other relevant biological, psychological, or social factors) and the causal relationships among these components. The components of the network include the experiences we commonly refer to as symptoms. In other words, a pattern of pervasive worry is not caused by generalized anxiety disorder, the pattern of pervasive worry (and accompanying features) is generalized anxiety disorder.

This idea is illustrated in

Figure 1. In this figure, there is no independent panic disorder node that causes panic attacks, avoidance, and worry. Instead, panic disorder is a state that the network can be in: a state characterized by the presence of these specific experiences. The stable, concurrent presence of panic attacks, avoidance, and worry is panic disorder. In other words, network theory provides an explanation for the observation that some symptoms tend to cohere as syndromes that obviates the need for an independent underlying cause. In doing so, it challenges the assumption that mental illnesses must necessarily exist independently of their signs and symptoms.

Notably, when taken literally, the term “symptom” itself is incompatible with network theory. The word “symptom” denotes a surface-level indicator of an underlying cause. Network theory asserts that most things that have traditionally been called symptoms (e.g., worry) are not indicators of underlying diseases, but are nodes in a causal web. This idea—that many “symptoms” are in fact causal players—is a key concept in network theory. Moreover, some things that have not traditionally been called symptoms (e.g., the belief that bodily sensations associated with arousal are dangerous) fit nicely as nodes within these networks (e.g., panic disorder) (

13–

14). Therefore, we prefer the terms “nodes” or “elements” rather than “symptoms” when speaking of the constituent parts of networks, because these terms clarify that these parts can be understood not as passive indicators, but rather as active causal components that constitute the mental disorder.

Assumption 2: Classification of Psychological Problems Should Follow the Medical Model

Many medical conditions can be summarized by a classification system that simultaneously describes both cause and consequence. When a certain medical symptom pattern arises (dizziness, shakiness, sweating), physicians are tasked with providing a differential diagnosis to determine which disease entity has led to the symptoms (influenza or hypoglycemia). By identifying the presence of the disease entity (which, together with the symptoms, constitutes a cause-consequence pair), the physician can typically rule out the presence of other disease entities. Such classification systems can be used to great effect when specific causes (i.e., diseases) reliably lead to the same general consequences (i.e., symptoms), when some consequences are unique to a given cause (e.g., pathognomonic symptoms, such as Koplik spots), when the different causes are mostly independent of one another, and when the consequences do not feed back into the causes (e.g., dizziness from hypoglycemia does not cause the flu). We will here refer to such cause-consequence classification systems as a medical model of classification, although we note that this phrase is fraught, defined in different ways by different sources, and an oversimplification of the actual practice of modern medicine.

The network perspective challenges the assumption that classification should follow this simple medical model. Most fundamentally, as we argued in the previous section, it does so by demonstrating that there need not be an independent underlying cause that gives rise to symptoms and, thus, there need not be an underlying disorder to which the symptoms can be attributed. However, there are other characteristics of psychopathology that further argue against a simple cause-consequence classification system. First, the boundaries between our diagnostic categories are fuzzy, with many symptoms appearing across multiple disorders. Second, equifinality (a given end state can be reached by many different starting points) and equipotentiality (many given end states can be reached from the same starting point) tend to be the rule, rather than the exception, in psychiatry. A given component in psychiatry (e.g., impaired sleep) can have diverse consequences (e.g., poor concentration, mania), and a given consequence may have many potential causes (e.g., poor concentration may arise not only from impaired sleep, but also from anhedonia, preoccupying worry, or intrusive memories of trauma). Third, symptoms in psychiatry are often causal agents with their own set of effects. In an idealized medical model, observable symptoms are the endpoint of the causal system: dizziness arising from hypoglycemia does not cause the flu, allowing diagnosticians to confidently rule out the flu if they attribute dizziness to hypoglycemia. In practice, things are perhaps not so simple (e.g., dizziness may not cause the flu, but it may lead to nausea, falls, or other health consequences), but this general framework holds well enough to make informative diagnostic decisions.

In psychiatry, the complex web of causality is even more dense. For example, anxiety about social situations can (and frequently does) result in problematic patterns of alcohol use, which may give rise to feelings of worthlessness, loneliness, and depression. Similarly, intrusive memories following a trauma may evoke physiological reactivity and, in turn, fatigue, social disconnection, anhedonia, and irritability. In other words, symptoms are not the end of the causal story; they frequently result in consequences that do not respect diagnostic boundaries. Together, these commonly observed features of psychopathology present significant obstacles for a medical model of classification.

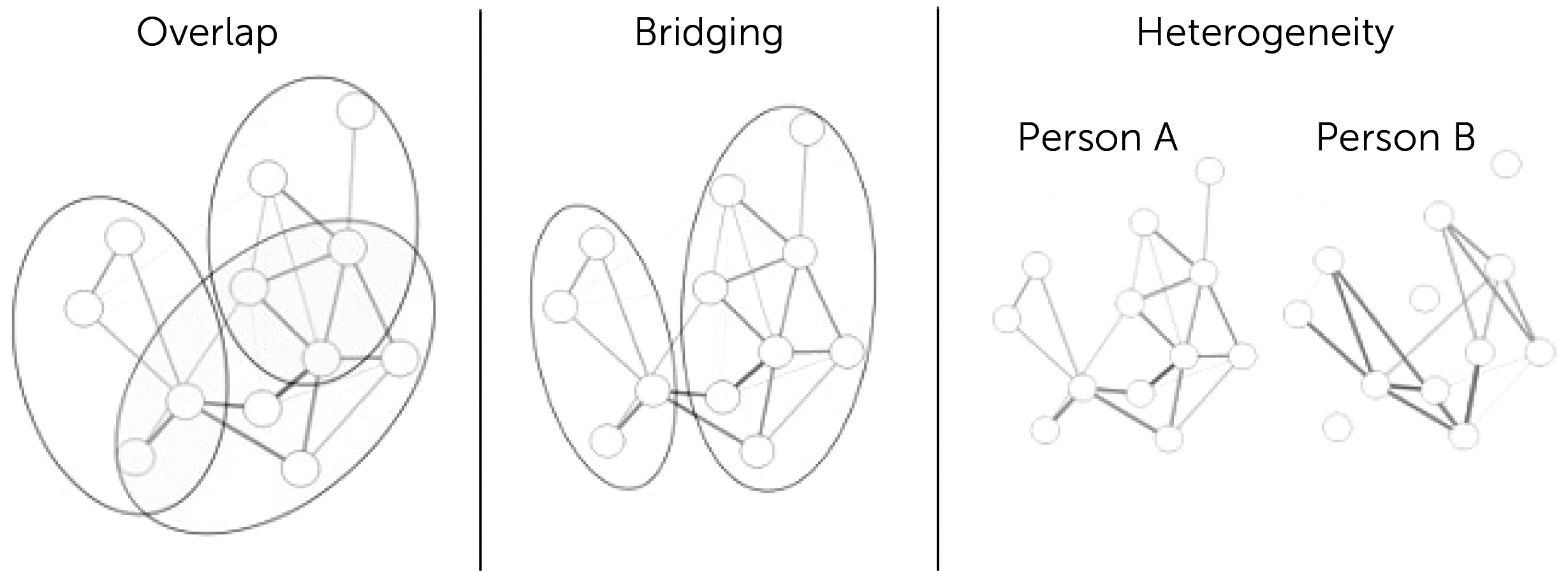

Viewing psychopathology from a network lens provides a new perspective on these obstacles. As depicted in

Figure 2, the fuzziness among diagnostic categories arises because mental disorders are overlapping communities of causally interacting components, not discrete disease entities. For example, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms overlap considerably with the symptoms of depression, a substantial challenge for diagnosticians working from a medical model, but an expected state of affairs when viewed from a network perspective, where individual symptoms can have a range of causal effects. Even in the absence of syndromic overlap, syndromes may bridge to each other if the symptoms of one disorder cause symptoms of another (e.g., persistent social anxiety may lead to problematic alcohol use). In addition, network theory allows that similar components may have divergent effects, thereby producing considerable heterogeneity across individuals in symptom presentation.

To be clear, our argument is not that classifications are useless in the context of network theory or that these classifications should be avoided altogether. Even rough, messy, and imprecise classification systems can be useful for quickly summarizing and communicating information in a

lingua franca (

15). For example, knowing that a patient has a diagnosis of panic disorder provides us information about potential causal relationships among panic attacks, worry, and avoidance that may produce this pattern of symptoms. However, it is important that the diagnoses in our classification systems are treated as rough shorthand and not as established independent disease entities.

In situations where classification is complex, it is often beneficial to have multiple systems of classification depending on one's goals (e.g., one classification system for treatment and another for etiology) (

16). Indeed, multiple classification systems have been used productively in biology, and such a system could readily apply to clinical psychology (

16,

17). As an example, consider that treatments for depression show different efficacy for different people, and this does not seem closely linked to the depression diagnosis as defined by its

DSM signs and symptoms. Indeed, the treatments with the best evidence for depression (antidepressant medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy) are not even specific to depression at all (

18–

20). In developing a treatment-focused classification system, other variables might be more important than the same symptom patterns we have relied on for years. For instance, one study (

21) has found that marital status (being married or cohabiting) predicts an advantage of cognitive-behavioral therapy over antidepressant medication among individuals with depression. In a treatment-focused classification system, marital status might be an important variable to consider (perhaps more important than the specifics of the symptom patterns). Classification systems could also rely on the within-person temporal dynamics of variables and relationships between variables, rather than just on the presence or absence of the variables (

22). In sum, there may be advantages in departing from psychiatry’s traditional view of classification.

Assumption 3: Psychological Problems Are Caused by Diseases or Aberrations in the Brain

Perhaps most controversially, the network theory challenges the idea that psychological problems are caused by illnesses in the brain. Borsboom, Cramer, and Kalis (

23) have presented three arguments for why a network view is incompatible with a reductive explanation of mental illnesses as brain disorders. Their first argument juxtaposes the “many causes” network model with a “common cause” brain disorder. If all symptoms are simultaneously dependent on a common latent variable, then one can accurately describe the system in terms of a common cause (in the brain). However, if a network model is correct, and there are many interacting causes, this type of reduction is blocked. Second, they argue that it is implausible that neurobiological causes could be a simultaneous explanation for all symptoms, because many symptoms are rational in the context of the specific content of other symptoms (e.g., hand washing is rational when one believes one has been contaminated). The specific content of thought is therefore necessary to explain the full symptom pattern. The fact that many symptoms are “intentional” (i.e., about something) means that there are an infinite variety of possible symptom manifestations. A small difference in thought content could lead to radical differences in behaviors or other symptoms. Third, they argue that specific connections in symptom networks rely on cultural and historical contexts, again blocking the idea that mental illnesses can be reduced to a single common cause in the brain invariant to context.

Critically, this does not mean that psychological problems cannot result from insults to or impairments in the brain—history is replete with such examples, from syphilitic insanity to postconcussive syndrome. Rather, it provides a plausible alternative to this model that may apply to some specific types of problems. Equipped with this alternative account, we can begin to ask which type of theoretical framework offers the best explanation for a particular syndrome. Given the lack of progress in identifying reliable brain markers of most mental problems over the past century, we believe there is good reason for us to devote greater energy to alternative accounts, such as network theory.

We would again emphasize that our call to further investigate alternative accounts need not be an inflammatory position—network theory does not assert that structural or functional abnormalities in the brain are irrelevant. Within the framework of network theory, brain processes can be viewed as a separate level of analysis that can help explain the connections among nodes (

6). Alternatively, these processes could be directly incorporated as components that play an important role within the network, providing a biopsychosocial network that accounts for the complex interplay among components across separate levels of analysis (

13). Ultimately, we suspect that an integration of network theory with research on the genetic and neurobiological factors that contribute to psychopathology will be the most fruitful path toward meaningful progress in psychiatric research and practice.