INTRODUCTION

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe and persistent mental illness with a lifetime prevalence of 2%–3%.

19,22,23 Unfortunately, treatment outcomes remain poor, particularly for depressive episodes, with over one-third of patients failing to adequately respond to multiple first-line treatments (i.e., treatment-resistant bipolar depression; TRBD).

7,11,20,38 Lithium has been shown to reduce suicide rates; however, BD continues to be associated with extremely high rates of suicide (primarily during depressive and mixed episodes) with 23%–26% attempting suicide and 5%–10% completing suicide.

28,36 Pharmacotherapy (e.g., conventional mood stabilizers and antipsychotics) remains the primary treatment for BD, however, there remains high rates of treatment resistance, relapse, and problematic adverse effects, including metabolic effects, sedation, cognitive dysfunction, and renal impairment.

43,44 Therefore, novel treatments are urgently needed for BD, with a focus on treatments that will have greater antidepressant and anti-suicidal effects with less adverse effects, including considerations for treatment-emergent manic symptoms.

8,19,22,23,41Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic with growing evidence to support acute antidepressant effects at sub-anesthetic doses (e.g., 0.5–1.0 mg/kg infused over 40–60 min).

19,21,22,23,24,25,35 Ketamine primarily targets the glutamate system, rather than the more conventionally targeted monoamine systems.

34,46 Over the past two decades, growing evidence has supported rapid and robust antidepressant effects of sub-anesthetic doses of intravenous (IV) ketamine for treatment-resistant depression (TRD).

3,4,19,22,23,48 However, the majority of IV ketamine randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been single-dose, proof-of-concept studies, primarily in major depressive disorder (MDD) samples.

2,4,19,22,23,48 More recently, the importance of repeated doses of IV ketamine (twice or thrice weekly over 2 weeks) has been demonstrated to have greater antidepressant effects compared to a single dose, approximately doubling the antidepressant response rate and sustaining antidepressant effects longer.

1,18,19,22,23,37,39 However, no RCT has evaluated the effects of repeated doses of IV ketamine specifically for TRBD, as previous studies were either exclusively with MDD samples, or mixed MDD/BD samples with only a small proportion of BD participants.

18,19,22,23,29As summarized in recent reviews, results from completed RCTs primarily support the effect of IV ketamine in MDD samples, with minimal research in BD samples.

4,16,18,19,22,23,29 Only small, single-dose IV ketamine RCTs were identified in BD samples with no completed repeat dose BD RCTs (neither IV ketamine nor intranasal (IN) esketamine).

4,16,18,29 While ketamine is not FDA-approved for any mental disorder, its isomer, esketamine, is the first FDA-approved non-monoamine-based psychotropic agent for adults with TRD. The FDA approval of the intranasal esketamine was based on results from replicated, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials.

15 In addition to the proven efficacy of esketamine, the short-term efficacy of intravenous (IV) ketamine is established.

3,4,5,17,27,30,39,42 Currently, ketamine is recommended in select medication treatment guidelines for MDD as a treatment option when two prior antidepressants are insufficient.

14,26Two small, proof-of-concept, crossover RCTs in BD samples found that a single ketamine infusion (0.5 mg/kg over 40 min) was associated with rapid and robust antidepressant effects, with reductions in depression severity observed within hours and effects lasting for 3 days, with moderate to large effect sizes (

d = 0.6–1.1).

6,48 An additional proof-of-concept RCT demonstrated rapid reductions in suicidal ideations in TRBD with a single ketamine infusion.

10 Notably, the generalizability of these findings in the real-world setting remains unclear given the higher degree of complexity and comorbidity of TRBD in clinical settings.

The objective of the present study is to evaluate the real-world effectiveness of repeated ketamine infusions for TRBD in a community clinic setting. Our group has previously published effectiveness studies for TRD and various subgroups from our clinical sample

19,22,23,32,33; however, the present analysis is the first comprehensive report focused exclusively on our TRBD sample. These realworld effectiveness studies may complement RCT data to provide a more well-rounded understanding of the clinical utility of ketamine for TRBD.

45METHODS

Participants and study design

All of the data presented herein were obtained from patients who were referred to the Canadian Rapid Treatment Center of Excellence (CRTCE) in Mississauga, Ontario, Canada. The CRTCE is the first Canadian clinic offering IV ketamine to adults (i.e., age ≥18 years) with TRD as part of MDD or BD outside of clinical trials. Eligibility criteria to receive IV ketamine and the protocol for the CRTCE have been previously described (

19,22,23). In brief, patients must have failed at least two adequate medication trials and not have any medical (uncontrolled hypertension, pregnancy) or psychiatric contraindications (active psychosis or current substance use disorder).

Current ketamine administration guidelines

21,24,25 suggest that patients begin by receiving a series of two to three infusions per week over 2–4 weeks followed by maintenance infusions. Prior to their first infusion, all patients were medically cleared by CRTCE staff anesthesiologists that evaluated patients for any unstable medical disorder contraindicated against IV ketamine (e.g., malignant hypertension, supraventricular tachycardia, etc.). All CRTCE patients started with two infusions of ketamine hydrochloride 0.5 mg/kg diluted in 0.9% saline solution infused over 40 min, with a potential to increase dose up to 0.75 mg/kg for the 3rd and 4th infusions if inadequate response (i.e. ≤20% reduction in total depression symptom severity as measured by the QIDS-SR

16) is observed at the starting dosage. To this end, patients at the CRTCE received four infusions delivered across 8–14 days based on their availability/scheduling. For each patient, a post-treatment assessment visit was scheduled 1 week after the fourth infusion.

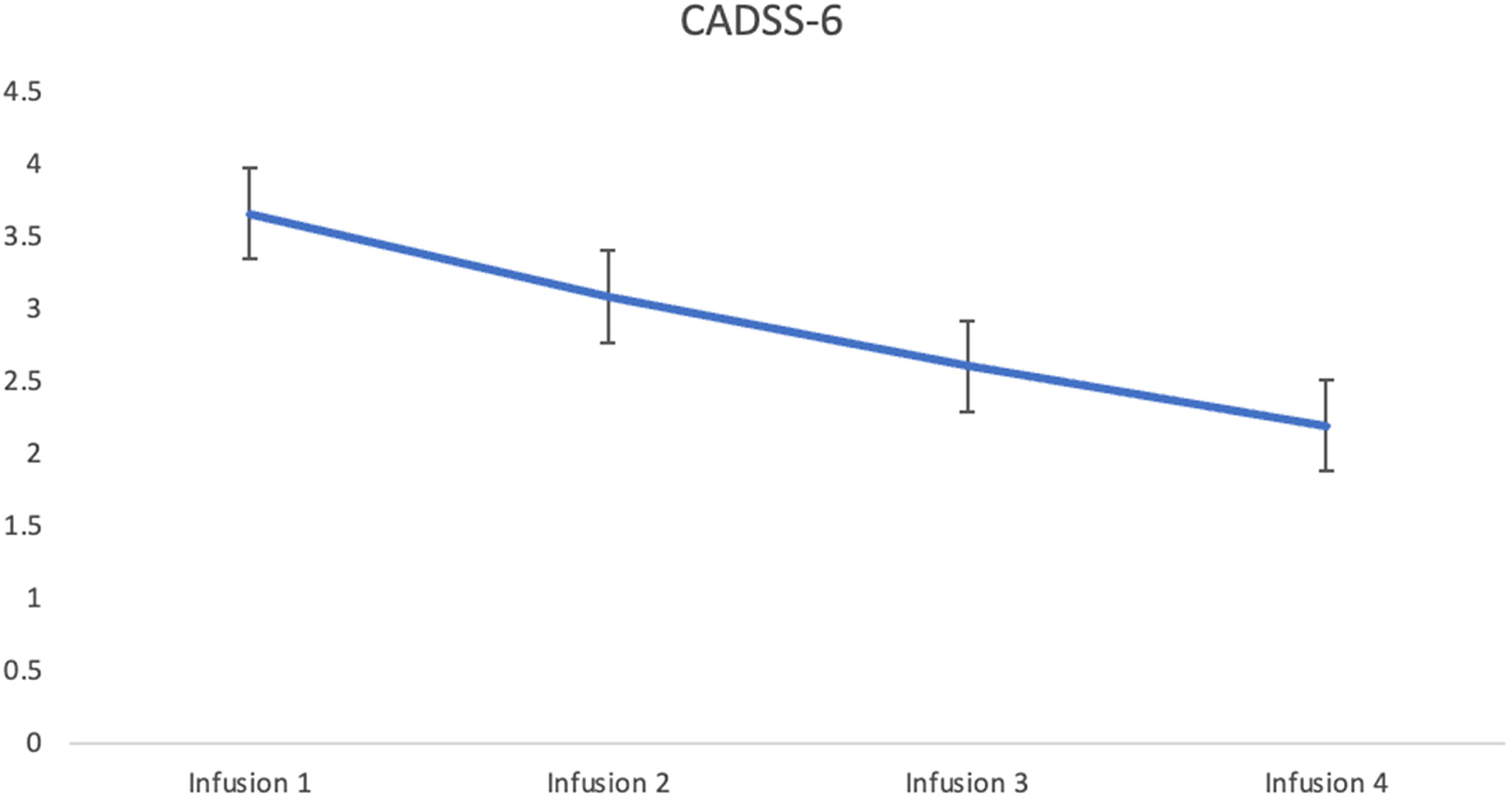

Tolerability and safety were assessed during, and immediately following each infusion. The CRTCE anesthesiologists and nurses assessed safety by measuring vital signs, oxygen saturation, and pulse oximetry. Tolerability to ketamine was assessed through reported treatment-emergent adverse events (e.g., nausea, dizziness, depersonalization, etc.). Lastly, dissociative symptoms from ketamine were evaluated by the 6-item Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS-6) 5–10 min immediately after infusion.

33The primary clinical measure obtained in this study was the Quick Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report 16-Item (QIDS-SR16). The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7), Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) were also used as secondary measures. Participants completed the QIDS-SR16 prior to their first infusion (i.e., baseline infusion), at each subsequent infusion during the initial protocol, and finally during the follow-up with the clinic psychiatrist (i.e., post-treatment assessment visit). Participants completed the GAD-7 and SDS at baseline, post-infusion 3, and posttreatment assessment visits.

Herein, we report on 66 outpatients (Mage = 45.7, age range: 22–77) from the CRTCE who received care from July 2018 to November 28, 2019, with either TRBD type I or II. This analysis was approved by a community Institutional Review Board and registered under NCT04209296 on the clinicaltrials.gov website.

Data Collection, Reporting, and Analysis

The primary outcome was the change in the total QIDS-SR

16 score from baseline to the post-treatment assessment visit. Secondary outcomes were changes from baseline to the post-treatment assessment visit in the QIDS-SR

16 suicidality item, total GAD-7, and SDS scores. Psychosocial functioning was measured using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). The CADSS-6 was used and developed from questions 1, 2, 6, 7, 15, and 22 from the full-length CADSS.

31Missing data and unequal timing between study visits were managed by a one-way mixed model. The covariance matrix that was used was autoregressive based on a lower Akaike's Information Criterion (AIC). Sex and age were used as covariates in the mixed model analysis to evaluate GAD-7 scores, SDS work, social, and family item scores, and mean QIDS-SR SI scores. Baseline depressive severity was also taken into account in evaluating specifically the QIDS-SR16 total scores. Lastly, a two-way mixed model was used to evaluate the differences between BD1 and BD2.

Pairwise comparisons were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method. A responder/remitter analysis was then conducted to ascertain our results. The response and remission rates were calculated as follows: QIDS-SR16 total score reduction from baseline ≥50% for response and QIDS-SR16 total score ≤5 for remitter.

RESULTS

Sample

A total of 66 patients received IV ketamine at the CRTCE when this analysis was conducted. Seven patients were excluded from the responder/remitter analysis due to the absence of baseline and post-infusion QIDS-SR

16 scores. Of the total sample of 66 patients, 28 were BDI, 35 were BDII, and we were unable to stratify the remaining 3 due to lack of clarity in reviewed medical records. Demographic information, including patient sex, age, BMI, mean number of prior and current psychotropics and the number of patients that received a dose increase are reported in

Table 1 for the total sample and BDI/ BDII samples.

Depressive Symptom Severity

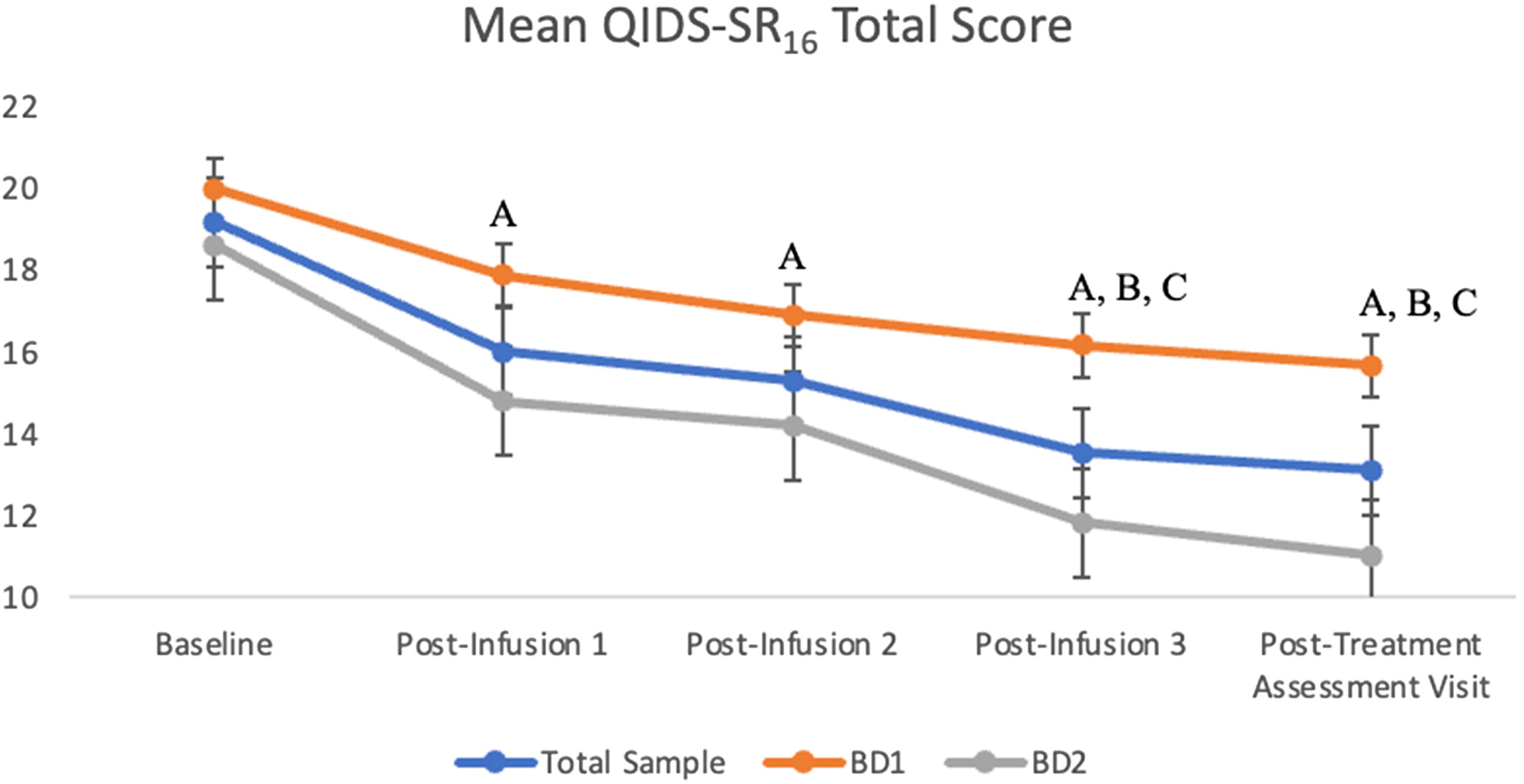

The first set of analyses consisted of the combined analysis of the BDI and BDII subgroups. Overall, there was a significant main effect with a moderate effect size of infusion on QIDS-SR16 total score: F(4, 197.9) = 16.8, p < 0.001, Cohen's f = 0.56. There was a significant reduction in QIDS-SR16 score from baseline to all subsequent timepoints (ps < 0.001). Moreover, there was a significant reduction in QIDS-SR16 score from post-infusion 1 to post-infusion 3 (p < 0.001) and post-treatment assessment visit (p < 0.05). There was also a significant reduction in depression score in the post-infusion 2 score compared to the post-infusion 3 and post-treatment assessment visit (ps < 0.05). There were no significant differences in scores between post-infusion 1 to post-infusion 2 and also no significant differences in scores between post-infusion 3 to post-treatment assessment visit (ps >0.05).

A separate two-way model with group and time as independent variables was completed. Initially, we found a significant main effect of BDI versus BDII subgroups on QIDS-SR

16 total scores: F(1, 64.36) = 5.14,

p = 0.027, η

p2 = 0.074. However, the effect was lost when controlling for baseline depression severity: F(1, 61.11) = 2.50,

p = 0.12, η

p2 = 0.039. Nevertheless, it is important to note that there was a trend toward better outcomes in BDII. The results of the mean QIDS-SR

16 score of the overall sample of patients and of the BDI and BDII subgroups are presented in

Figure 1.

The results of the responder and remitter analysis are presented in

Table 2. At follow-up, 16 (35%) patients achieved a response of ≥50%; and 21 (46%) patients improved by at least 25%. Lastly, 9 (20%) patients met remission criteria.

Suicidality

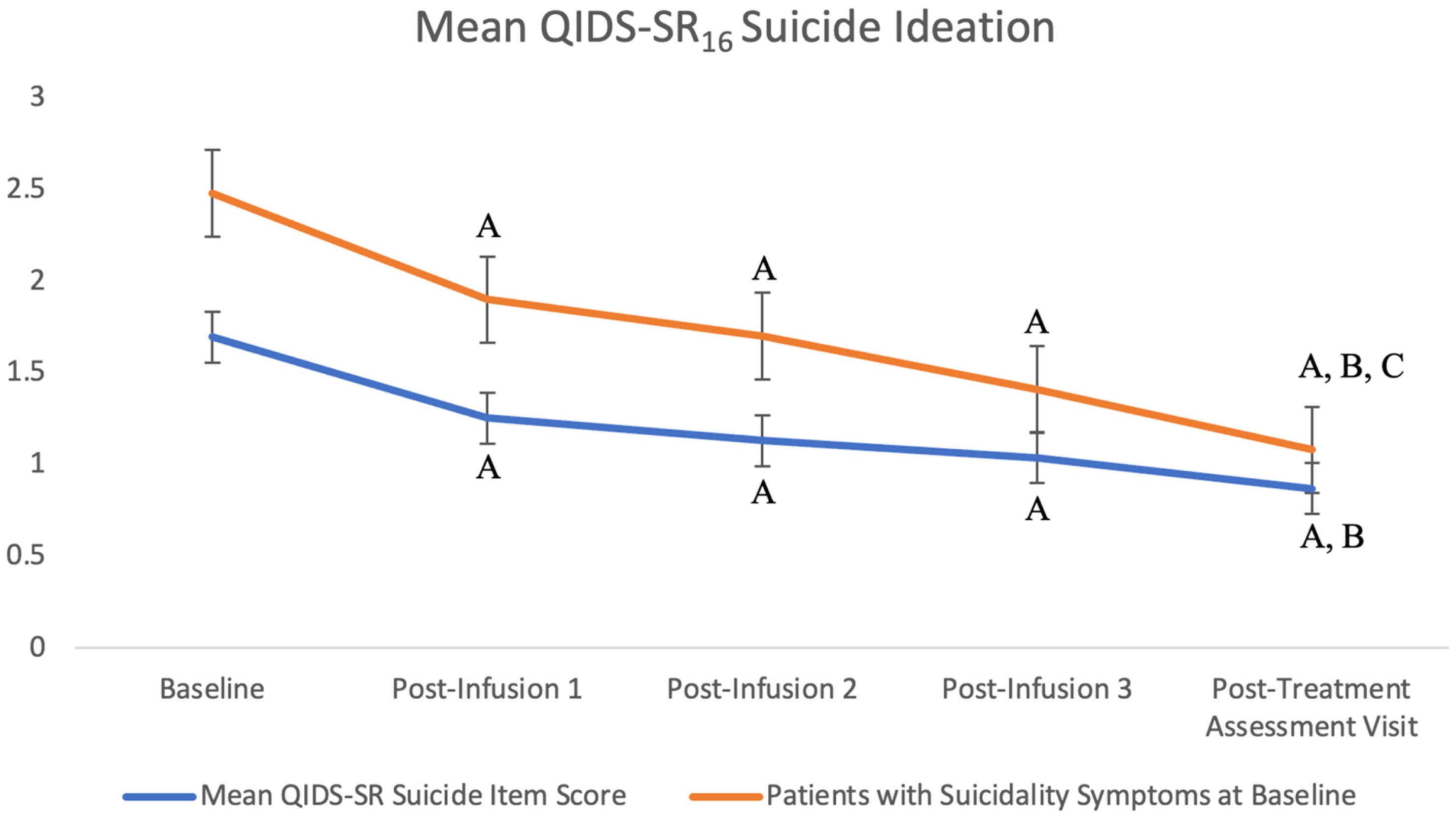

The QIDS-SR16 suicidality item score significantly decreased over time with treatment, F(4, 197.9) = 16.8, p < 0.001, Cohen's f = 0.56. There was a significant reduction in suicidality score from baseline to post-infusion 1, post-infusion 2, post-infusion 3, and post-treatment assessment visit score (ps < 0.001). Additionally, there was a significant improvement from the post-infusion 1 score to post-treatment assessment score (p < 0.05). Lastly, there was no significant main effect of BDI versus BDII subgroups on QIDS-SR16 suicidality item score: F(1, 65.31) = 0.004, p > 0.05.

Overall, 8 (14%) patients presented at baseline without exhibiting any symptoms of suicidality (i.e., QIDS-SR16 suicidality item = 0). Suicidality scores were then sub-analyzed considering only patients who presented with high QIDS-SR16 suicidality item scores of 2 and 3 at baseline (n = 33) and there remained a significant decrease over time with treatment F(4, 104.8) = 12.93, p < 0.001, Cohen's f = 0.66.

There was a significant reduction in this sub-analysis of suicidality scores from baseline (

M = 2.48, SE = 0.09) to post-infusion 1 (

M = 1.9, SE = 0.16;

p < 0.001), post-infusion 2 (

M = 1.70, SE = 0.18;

p < 0.001), post-infusion 3 (M = 1.41, SE = 0.20;

p < 0.001), and post-treatment assessment (

M = 1.08, SE = 0.21;

p < 0.001). Moreover, suicidality symptoms significantly decreased from post-infusion 1 to post-treatment assessment and from post-infusion 2 to post-treatment assessment (

ps < 0.05). The results of the mean QIDS-SR

16 suicidality item score of all patients and those who reported suicidality at baseline are presented in

Figure 2.

Anxiety Symptoms

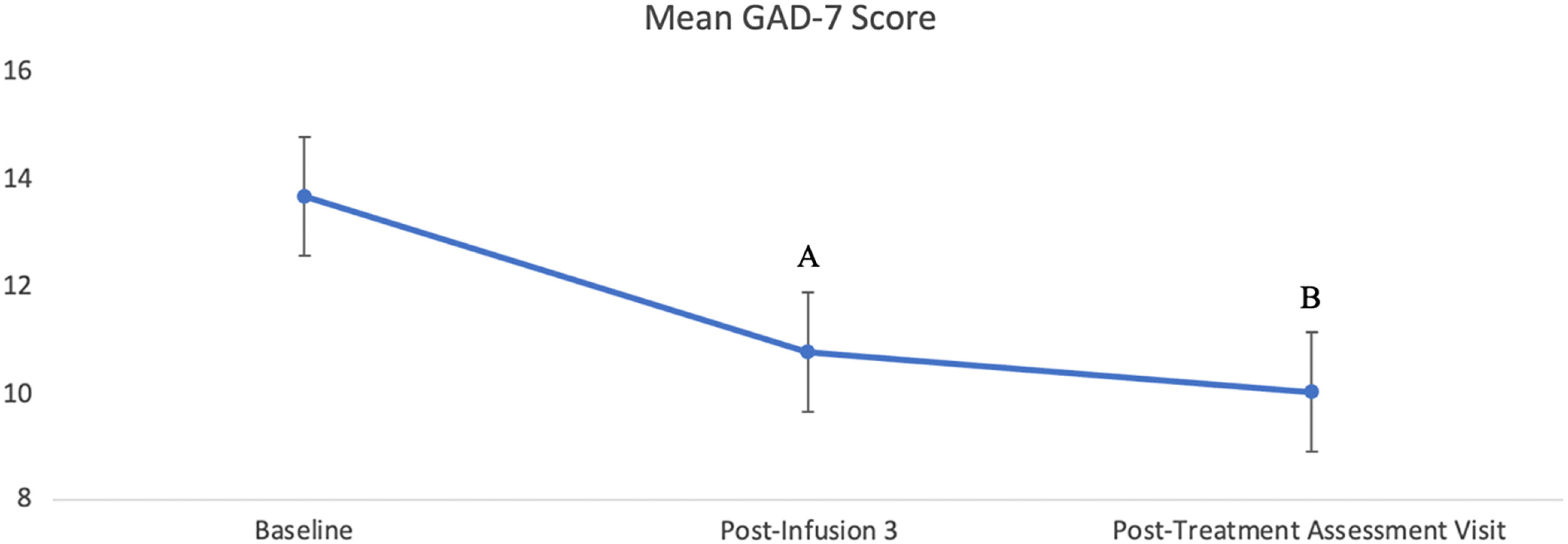

A total of 59 patients had available scores in the GAD-7 at baseline, 44 patients had available scores at post-infusion 3, and 45 patients had available scores for the post-treatment assessment visit. There was a significant effect of infusion for the treatment of anxiety, measured by the GAD-7, F(2, 82.5) = 8.99,

p < 0.001, Cohen's

f = 0.43. After adjusting for multiple comparisons, the results indicated a significant decrease from baseline anxiety score to post-infusion 3 (

p < 0.05) and from baseline to post-treatment assessment (

p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in GAD-7 scores between the post-infusion 3 and post-treatment assessment visit (

p = 0.357). Lastly, there was no significant main effect of BDI versus BDII subgroups on GAD-7 scores: F(1, 56.19) = 1.06,

p > 0.05. Change in mean anxiety scores following ketamine infusion is presented in

Figure 3.

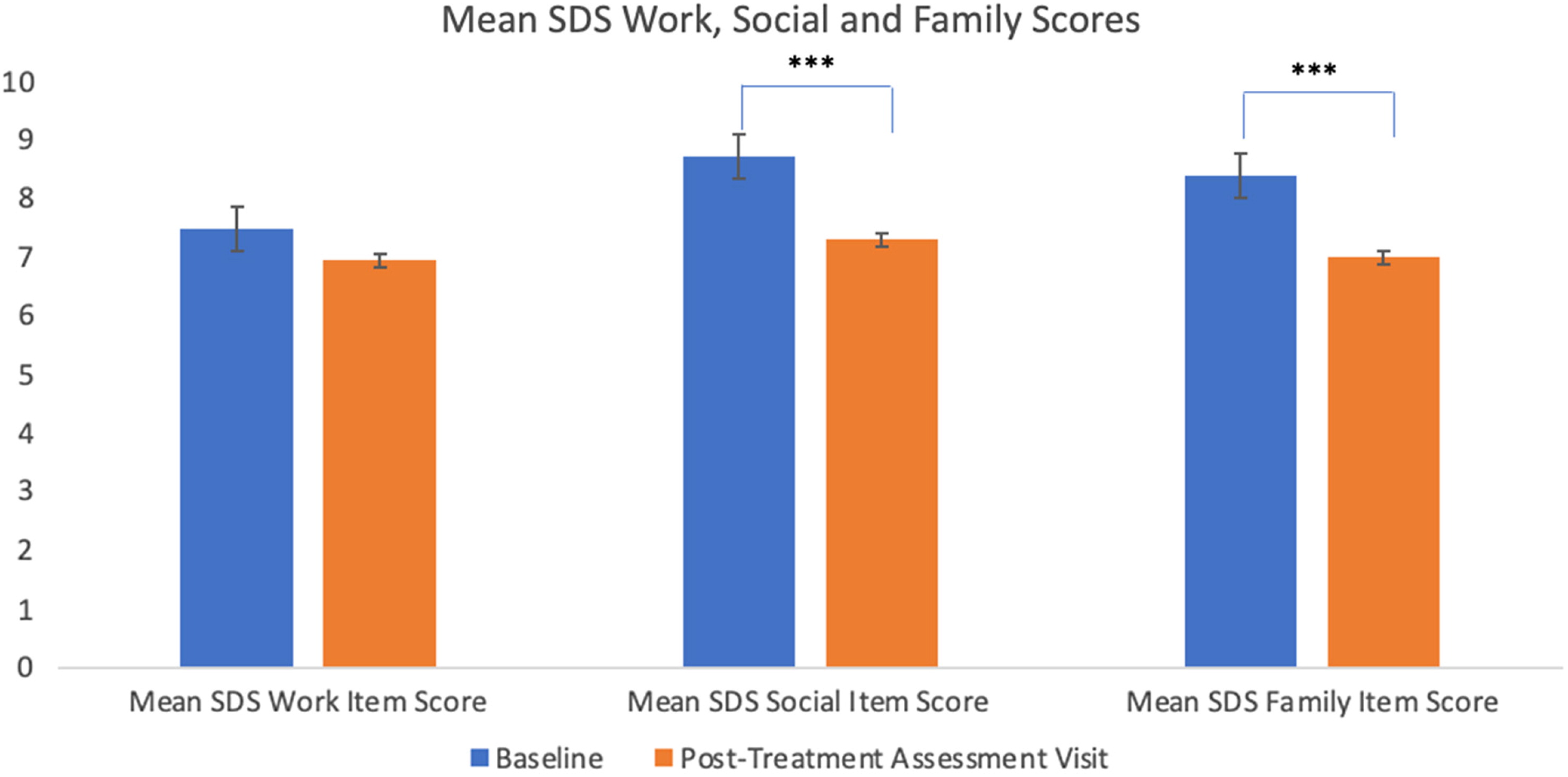

Psychosocial Functioning

A total of 32 patients had available scores for the SDS-WORK at baseline, 28 patients had available scores at post-infusion 3, and 21 patients had available scores for the post-treatment assessment visit. There was no significant main effect of infusion, F(2, 52.1) = 0.61, p > 0.05, Cohen's f = 0. There was no significant main effect of BDI versus BDII subgroups on SDS-WORK scores: F(1, 45.9) = 0.27, p > 0.05.

A total of 58 patients had available scores for the SDS-SOCIAL at baseline, 42 patients had available scores at post-infusion 3, and 45 patients had available scores for the post-treatment assessment visit. There was a significant main effect of infusion for the SDS-SOCIAL score, F(2, 76) = 10.83, p < 0.001, Cohen's f = 0.50. The SDS SOCIAL scores significantly decreased (i.e. improved) from baseline to post-treatment assessment visit and from post-infusion 3 to posttreatment assessment visit (ps < 0.001). There was no significant difference between baseline and post-infusion 3 for SDS-SOCIAL scores (p > 0.05). There was no significant main effect of BDI versus BDII subgroups on SDS-SOCIAL scores: F(1, 54.7) = 1.06, p > 0.05.

A total of 58 patients had available scores for the SDS-FAMILY at baseline, 37 patients had available scores at post-infusion 3, and 45 patients had available scores for the post-treatment assessment visit. There was a significant main effect of infusion for the SDS-FAMILY score, F(2, 76.5) = 8.73,

p < 0.001, Cohen's

f = 0.44. The SDS-FAMILY scores significantly decreased from baseline to post-infusion 3 and from baseline to post-treatment assessment visit (

ps < 0.05). There was no significant difference between post-infusion 3 and post-treatment assessment visit for Family scores (

p > 0.05). There was no significant main effect of BDI versus BDII subgroups on SDS-FAMILY scores: F(1, 64.18) = 2.94,

p > 0.05. Change in mean score of the SDS Work, Social, and Family subscales are presented in

Figure 4.

Safety and Tolerability

Safety and tolerability were assessed during, and immediately following each infusion. Ketamine infusions were generally well tolerated with treatment-emergent hypomania observed in only three patients (4.5%) with zero cases of mania or psychosis. In these three cases, hypomania emerged after the third or fourth infusion. No hypomania emerged after the first or second infusion. All three patients were also co-prescribing an antidepressant that may have impacted the risk of hypomania emerging. Two patients were treated with a therapeutic dose of an SGA and one was not on a mood stabilizer. Of note, after these cases were identified, we now strongly recommend all patients with BD continue mood stabilizers at a therapeutic dosage prior to starting infusions. In this regard, patients in our study were on a variety of medications including mood stabilizers (lithium, lamotrigine, etc.), psychostimulants (Vyvanse, Adderall, Concerta, etc.), sedatives (clonazepam, lorazepam, etc.), SSRIs (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, vortioxetine, sertraline, citalopram, etc.), TCAs (imipramine, nortriptyline, etc.), SNRIs (duloxetine, desvenlafaxine, etc.), and adjunctive agents (lurasidone, modafinil, aripiprazole, etc.).

Dissociative symptoms from ketamine were evaluated by the Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS) 5–10 min post-infusion. After adjusting for age and sex, there was no significant main effect of infusion: F(3, 167.8) = 0.659,

p = 0.578. The cut-off score of three or higher for the presence of dissociation was determined using discriminant function analysis.

31 Mean CADSS-6 scores were: 3.65 (3.27), 3.08 (3.45), 2.60 (2.96), and 2.19 (3) for infusions 1, 2, 3, and 4 respectively. In keeping with the cut-off score, patients experienced dissociative symptoms, similar to that observed in MDD in previous studies during infusion 1 and 2. No dissociative symptoms were observed in patients during infusions 3 and 4. Mean change in dissociation severity, as measured by the CADSS-6, over four infusions is presented in

Figure 5.

Tolerability to ketamine was assessed through reported treatment-emergent adverse events (e.g., nausea, dizziness, depersonalization, etc.). The most frequently reported adverse events included drowsiness (29.3%), dizziness (28.2%), blurred vision (26.8%), and confusion (26.8%).

Table 3 summarizes the number and percentages of reported treatment-emergent adverse. Adverse events were generally resolved within 1 h of each infusion.

DISCUSSION

We observed a clinically and statistically significant reduction in depressive symptoms (6.08±1.39 point reduction in QIDS-SR

16 score) following four ketamine infusions in our real-world treatment-resistant bipolar depression sample. We have previously established that a 3-point improvement on the QIDS-SR

16 is clinically relevant in adults with treatment-resistant depression receiving IV ketamine.

21,24,25 Importantly, no evidence of treatment-emergent mania or psychosis was observed with only low risk of treatment-emergent hypomania (4.5%).

Observed antidepressant response (35%) and remission rates (20%) were also substantial and clinically meaningful. Currently available data of repeated administration of ketamine, specifically in TRBD patients, remains scarce. Only uncontrolled, open-label studies using repeated ketamine infusions have been completed in BD samples with conflicting results.

55,56 Zheng et al. treated 16 TRBD patients with six ketamine infusions over 2 weeks with 21% responding (>50% symptom reduction) after the first dose, which increased to 74% responding after the sixth dose, with effects persisting up to 2 weeks after this final dose. Conversely, Zhuo et al.

49 completed an open-label study with 38 TRBD patients receiving a series of nine ketamine infusions over a 3-week period with antidepressant effects observed in the first week (e.g., after the first three infusions); however, the symptoms began to re-emerge in the second week with full relapse of symptoms by the third week of treatment. These divergent findings may have been secondary to atypical methods that were poorly described in these publications and the use of different scales (MADRS versus QIDS) and small sample sizes. Another possible explanation for the discrepancy in findings could be due to inherent variability in the levels of treatment resistance of patients in the different studies. Participants in the Zhuo study had at least two antidepressant trials, each lasting 12 weeks and required a relatively high level of severity for inclusion that could have contributed to patients relapsing. Whereas, our current study inclusion criteria are not as strict to represent a more “real-world” sample in that our study does not require that the trials occurred in the current episode. Our current study also permitted a ketamine dose increase at the third and fourth infusion, whereas the Zhuo study did not—providing another potential reason for the discrepancy in findings. Thus, further studies specifically involving TRBD patients with a larger sample size are needed to confirm these findings. To this end, our current study aimed to elucidate these findings with a larger sample. Taken together, our results support prior findings of repeated ketamine administration significantly improving the severity of depressive symptoms in TRBD patients.

Bipolar disorder is a psychiatric illness often associated with a high suicide rate and there is emerging evidence supporting ketamine's anti-suicidal effects (

9,13,20,21,23,24). Herein, we observed a significant decrease in suicidal ideation upon receiving just a single dose of ketamine, as measured by the suicidal ideation item of the QIDS-SR

16. We observed that with each subsequent dosage, suicidal ideation decreases correspondingly. These findings are also maintained for TRBD patients presenting with high QIDS-SR

16 suicidality item scores at baseline, further demonstrating ketamine's notable anti-suicidal effects. Equally noteworthy is that no patients reported amplification of pre-existing suicidal ideation due to ketamine infusions at any timepoint.

In addition to ketamine's rapid anti-depressive and antisuicidal effects, a significant reduction was also observed in anxiety symptoms. The significant 4-point reduction from baseline to post-treatment assessment visit in GAD-7 suggests a similar reduction from severe to moderate anxiety.

43 While there are currently no other published studies specifically examining the effects of repeated ketamine infusion on anxiety in TRBD patients, our observations remain in accordance with other studies on ketamine in adults with TRD, wherein a significant reduction in anxiety symptoms were also reported.

12,21,24,25,42With respect to psychosocial functioning, we observed a significant improvement in SDS “social” and “family” subdomains, but no improvement was seen in the “work” subdomain. It could be that workplace functioning has a longer latency to improvement than family/social subdomains due to practical reasons (e.g., patients may have been out of work and now that they are better, will need some time to find a job). This could possibly explain why the workplace score was not significantly improved during the time window assessed in our study. Nevertheless, there is insufficient reporting in the current literature of functional outcomes in adults with TRBD receiving repeated ketamine administration to draw conclusive findings. More research needs to be done examining the potential psychosocial and interpersonal benefits of repeated ketamine infusions in TRBD patients.

The main strengths of this study include a relatively large, complex, real-world sample, and the use of validated self-report measures. This is also the first study examining the effects of repeated ketamine infusions in a TRBD subgroup with delineating between type I and type II bipolar disorder. To our knowledge, our study represents the largest sample size of well-characterized adults with TRBD receiving repeated ketamine infusions at a community-based center. Moreover, a naturalistic dataset was used with minimal exclusion criteria (allowing patients to be enrolled with comorbidities, suicidality, and those who are currently using various antidepressants) thereby increasing the external validity and generalizability of the study in order to accurately reflect the varying population who might utilize ketamine as a treatment option.

The primary limitation of our study is the lack of a control group, as patients received open-label IV ketamine infusions. Furthermore, as our study was not conducted as part of a clinical trial, a large amount of data was missing due to patients skipping assessments and not completing all follow-up visits. Similarly, given that all patients received care at the CRTCE, they were required to cover the full cost (out of pocket or through insurance) of the treatment, resulting in a selection and possibly expectancy bias. Another limitation is that IV ketamine treatment was added on top of the variety of psychotropic medications the patients were already on, leading to potential confounds including patients having multiple comorbidities as well. Lastly, it is important to note that there is no evidence of a higher risk of mania or dissociation or psychosis in this population receiving this treatment.

24In summary, repeated infusions of IV ketamine were associated with improving depressive and anxiety symptoms, as well as psychosocial functional impairments in a well-characterized cohort of adults with TRBD. Future randomized, controlled studies are needed to further evaluate this new treatment, including consideration for acute and maintenance treatment, with these studies currently underway (NCT05339074, NCT05004896).