The Effectiveness of Lived Experience Involvement in Eating Disorder Treatment: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Objective:

Methods:

Results:

Discussion:

Public Significance:

Objetivo:

Método:

Resultados:

Discusión:

Introduction

Current Treatment Effectiveness

Lived Experience Mentoring in Mental Health

Lived Experience Mentoring and Eating Disorders

Aim of This Review

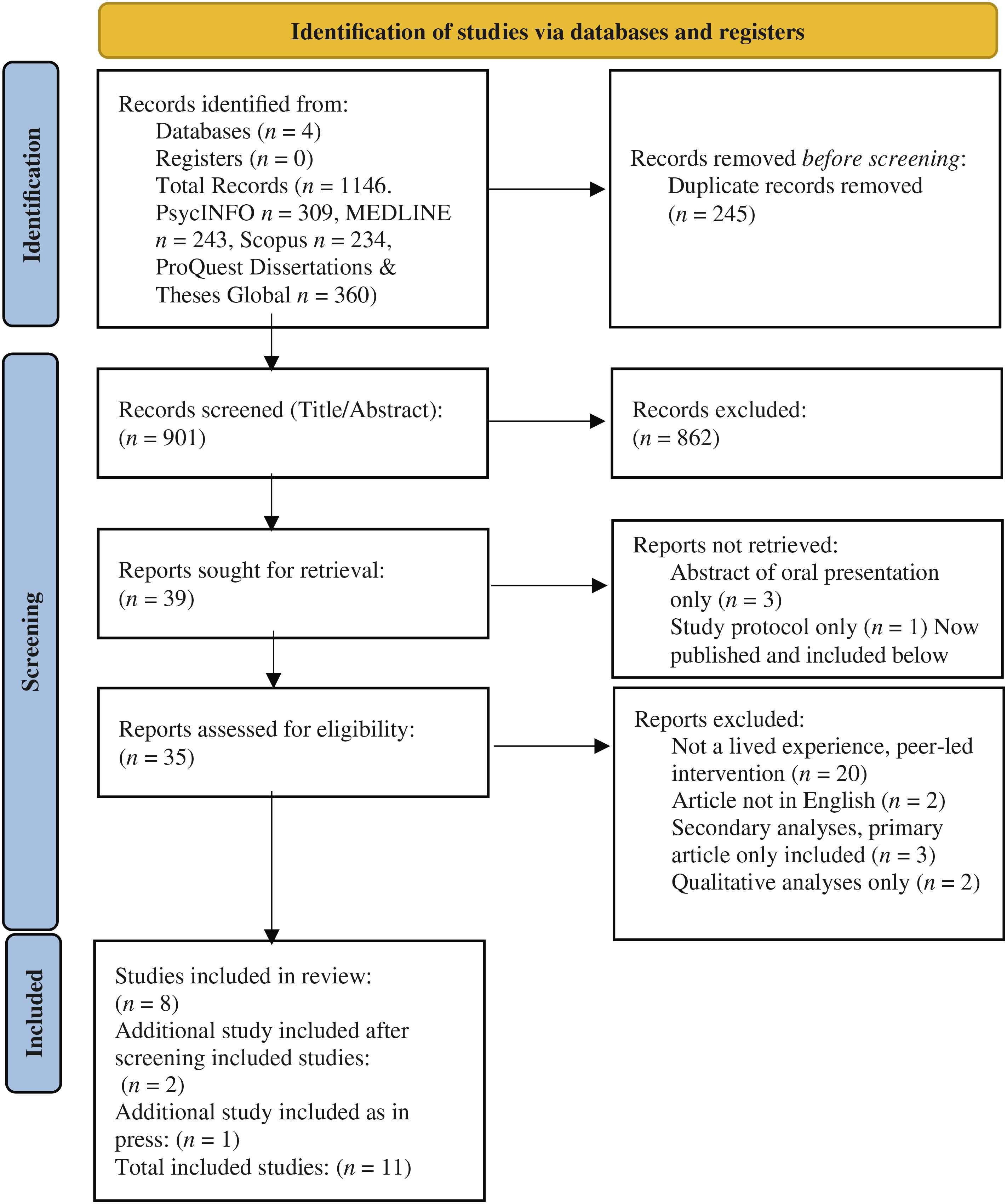

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Search Strategy

| Peer counseling | Eating disorders |

|---|---|

| peer* adj5 (provid*, consumer*, survivor*, specialist*, companion*, tutor*, educat*, mentor*, intervention*, listen*, mediat*, befriend*, therap*, work*, counsel*, support*), consumer* adj2 (provider*, survivor*, consultant*), peer* support*, mental health peer*, peer-led*, live experience*, mentor* | eating disorders, anorexia nervosa, binge eating disorder, bulimia, pica, “purging (eating disorders)”, anorexi*, bulimi*, purg*, bing*, OSFED, UFED, EDNOS, ARFID, orthorexia, pica, eat* adj2 disorder*) |

Review Strategy

Data Extraction

Study Quality Assessment

| Study | (4a) Eligibility criteria for participants | (5) The interventions for each group with sufficient details to allow replication, including how and when they were actually administered | (7a) Rationale for numbers in the pilot trial | (13a) For each group, the numbers of participants who were approached and/or assessed for eligibility, randomly assigned, received intended treatment, and were assessed for each objective | (13b) For each group, losses and exclusions after randomization, together with reasons | (15) A table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group | (16) For each objective, number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis. If relevant, these numbers should be by randomized group | (17a) For each objective, results including expressions of uncertainty (such as 95% confidence interval) for any estimates. If relevant, these results should be by randomized group | (26) Ethical approval or approval by research review committee, confirmed with reference number | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adamson et al. (2019) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | 7/9 |

| Beveridge et al. (2019) | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | 7/9 |

| Cardi et al. (2020) | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/9 |

| Hellner et al. (2021) | Y | Y | N | P | N | Y | Y | N | N | 4/9 |

| Hibbs et al. (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9/9 |

| Perez et al. (2014) | N | P | N | Y | P | Y | Y | P | P | 3/9 |

| Ramjan et al. (2017) | Y | P | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | 6/9 |

| Ramjan et al. (2018) | Y | P | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | 6/9 |

| Ranzenhofer et al. (2020) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | P | 7/9 |

| Rohrbach et al. (2022) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9/9 |

| Steinberg et al. (2022) | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | 5/9 |

| Study | Selection bias–Random sequence generation | Selection bias–Allocation concealment | Performance bias | Detection bias | Attrition bias | Reporting bias | Other bias | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardi et al. (2020) | Low Risk–Excel randomization used | Unclear Risk–Unknown if allocation predetermined | Unclear Risk–treatment centers blinded, unclear what participants told | Low Risk–Treatment centers blinded | Unclear Risk–Missing data handled well but attrition reasons not specified. Unequal attrition across groups–unclear if significant | Low Risk–Protocol published in advance and outcome data consistent with intentions | Low Risk–no other apparent bias | Some Risk |

| Hibbs et al. (2015) | Unclear Risk–External randomization but method not specified, and some randomization balanced by site and severity | Low Risk–Randomization by an independent database programmer | High Risk–No blinding (not possible) | Low Risk–Blinded assessors | Unclear Risk–Missing data handled well and use of ITT analyses. Unclear if attrition equal across groups. | Low Risk–Protocol published in advance and outcome data consistent with intentions | Low Risk–no other apparent bias | Some Risk |

| Ranzenhofer et al. (2020) | Low Risk–Random number generator used | High Risk–Blocks of 3 generated | High Risk–No blinding | Unclear Risk–Not reported | Low Risk–Attrition described well, ITT analyses | Low Risk–Outcomes pre-registered | Unclear Risk-Potential bias with recruitment (online methods not reported) | Some Risk |

| Rohrbach et al. (2022) | Low Risk–SPSS function to produce random numbers used | Low Risk–Blocks generated by independent researcher, concealed from principal researcher | High Risk–No blinding | Unclear Risk–Blinded assessors used for intervention check. Unknown remain outcomes | Low Risk–Attrition equal, missing data imputed, reasons specified | Low Risk–Protocol published in advance and outcome data consistent with intentions | Low Risk–no other apparent bias | Some Risk |

Results

Study Characteristics

| Study | Design | Intervention and modality | Tx group n | Control group n | Sessions N | Mentee characteristics (diagnosis, gender, age, ethnicity, SES indicators where reported) | Mentor characteristics (N, previous diagnosis, gender, age, ethnicity, SES) | Mentee outcomes | Mentor outcomes | Mentor training/ supervision and payment | Recovery criteria for mentors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adamson et al. (2019) | Case Series | Augmented inpatient treatment, integrating carers using ECHOMANTRA. Past recovered patients co-facilitated a group workshop for carers. Other elements of intervention were not peer led or co-led and were typically one-on-one. | 31 patients and 21 of their carers | 152 patients (audit data spanning 10 years) | 1 with carers involving a peer mentor. | Patients: All AN and female, age M=27.0 SD=8.8 (range not reported), years of education M=15.7 SD=3.1, ethnicity not reported. Comparison patients: All AN, age M=26.6 SD=8.7, years of education M=15.1 SD=3.2, gender and ethnicity not reported. | Not reported. | Patients: BMI, EDE-Q, WSAS, HADS, 2 motivation questions. Carers: DASS-21, EDSIS, PVA, CASK, AESED. | None. | Not reported. | Recovered, duration not reported. |

| Carers: 80% female, 66% employed, 20% historical issues of weight and shape concerns, other characteristics not reported. | |||||||||||

| Beveridge et al. (2019) | Case Series | Mentees currently receiving ED treatment. Mentors provided one-on-one peer and emotional support, shared recovery experiences. Development of a Wellness Plan with goals and sessions focused on achieving these. Modality not specified. | 30 | N/A | 13 (up to 3 h each, every 2 weeks). | AN=28, BN=1, OSFED=1. Female 93.3%, age 18–50 years (M=27.8, SD=9.5), 90% Australian, Employment Status=6 full-time and 5 part-time or casual, 11 students, 7 unemployed, one “other.” Highest education=tertiary by 13, secondary by 7, vocational by 3, and 5 currently studying. | N=17 (2 withdrew, characteristics are for n=15). AN=10, BN=3, BED=1, EDNOS=1. Female 93.3%, age 23–39 years (M=29.5, SD=4.3), 80% Australian, Employment Status=3 full-time, 4 part-time, 2 “other,” and 6 students, Highest Education=6 tertiary, 2 vocational, 1 secondary, 6 unreported. | BMI, EDE-Q, DASS-21, BDQ, AQoL-8D, online reflection exercises (qualitative). | EDE-Q, DASS-21, BDQ, AQoL-8D, online reflection exercises (qualitative). | 3-day training at start. Bimonthly group supervision with an ED clinician. Paid role. | 1 year. |

| Cardi et al. (2020) | RCT | RecoveryMANTRA + TAU or TAU. RecoveryMANTRA sessions one-on-one led by either a psychology student, carer or individual recovered from an ED. Workbook and video clips focused on recovery-orientated identity. Text-chat sessions. | 99 | 88 | 6 (1 h, weekly). | N=187. All AN. Female 96.8%, age M=27.81 SD=9.3 (range not reported), 97.5% White, Education Years M=15.47 SD=3.15, Employment Status: Part time=20%, Full time=35.3%, Housewife =2.7%, Sick leave=8.7%, Student=26.7%, Retired=1.3%, Other=5.3%. | N=24. Students n=13, carers n=2, recovered n=9, 91.7% female, age >19 (details not reported), ethnicity, SES, and previous diagnosis not reported. | BMI, EDE-Q, DASS-21, WSAS, motivation to change, therapeutic alliance, cognitive and behavioral flexibility | None. | Two 3-day trainings in motivational interviewing and RecoveryMANTRA, 2 day booster training twice/year. Weekly email or telephone supervision with ED experienced supervisor. Not reported whether paid or volunteered. | 2 years. |

| Hellner et al. (2021) | Case Study | Augmented FBT–peer mentor and family mentor included in treatment team. Peer mentor offered support and self-disclosure, role model for recovery. Family mentor offered support and advice on providing effective nourishment and limiting disordered behaviors. Virtual, one-on-one. | 2 families | N/A | Patient 1=4 peer mentor and 5 family mentor, Patient 2=4 peer mentor and 3 family mentor sessions. Over 4 weeks. Session duration not reported. | Patient 1=AN, age 20. Patient 2=Atypical AN, age 15. Gender, ethnicity and SES not reported. Carer demographics not reported. | Not reported. | Weight, satisfaction ratings, engagements, GAD-7, PHQ-9, EDE-QS | None. | Not reported. | Recovered, duration not reported. |

| Hibbs et al. (2015) | RCT | Evaluation of ECHO vs. TAU for families with a loved one in inpatient treatment. ECHO consisted of self-help book and DVDs and 5 telephone sessions with a coach per caregiver, one-on-one. | 86 patients and 134 of their carers | 92 patients and 134 of their carers | 5 per carer or 10 if a single carer, up to 40 minutes each, fortnightly. | Patients: All AN, Female 97% (ECHO), 93% (TAU), age 12.52–62.72 median=23.16 (ECHO), age 13.73–57.31 median=24.34 (TAU), White 93% (ECHO), 88% (TAU), Employment Status=full time 9% (ECHO) 9% (TAU), part-time 5% (ECHO) 7 (TAU), homemaker/unemployed/sick/retired other 56% (ECHO) 51% (TAU), student 29% (ECHO) 30% (TAU), Missing 1% (ECHO) 3% (TAU), Highest Level Education=No qualification 5% (ECHO) 5% (TAU), O/A Levels 47% (ECHO) 53% (TAU), University/higher degrees 47% (ECHO) 36% (TAU), Other 1% (ECHO) 1% (TAU), Missing 1% (ECHO) 4% (TAU). | N = 20 (5 post-graduate level psychologists, 15 recovered from an ED or carer of a loved one who has recovered). Demographics not reported. | Patients: BMI, EDE-Q, DASS21, WHO-QuoL, Client Service Receipt Inventory. Carers: Client Service Receipt Inventory, DASS-21, FQ, Accommodation and Enabling Scale for Eating Disorders, WHO-QuoL, EDSIS. | None. | 8 face-to-face training days and homework assignments over a 5-month period. Focused on cognitive interpersonal maintenance model, behavior change strategies, and motivational interviewing. Supervision via email, telephone, and face-to-face contact at a minimum of 2 sessions per family. Costs reimbursed but not paid for time (volunteered). | 2 years. |

| | | | | | | Carers: Female 60% (ECHO) 60% (TAU), age 22.22–78.54 median=52.22 (ECHO), age 19.7–78.88 median=53.18 (TAU), White 93% (ECHO) 93% (TAU), Employment Status=full time 40% (ECHO) 45% (TAU), part-time 22% (ECHO) 19% (TAU), homemaker/unemployed/sick/retired other 34% (ECHO) 33% (TAU), student 3% (ECHO) 1% (TAU), Missing 1% (ECHO) 3% (TAU), Highest Level Education=No qualification 8% (ECHO) 7% (TAU), O/A Levels 38% (ECHO) 28% (TAU), University/higher degrees 43% (ECHO) 49% (TAU), Other 9% (ECHO) 13% (TAU), Missing 1% (ECHO) 4% (TAU). | | | | | |

| Perez et al. (2014) | Case Series | Evaluation of MentorCONNECT, a one-on-one program. First phase initiation – establishing boundaries, contact, getting to know each other. Second phase – cultivation, topics vary but are recovery focused. Third phase – separation, mentee becomes less dependent on mentor. Various modalities (communication type as preferenced by mentors). | 58 (Matched with a mentor; M) | 49 (Unmatched–waiting to be matched, not randomized; UM) | Variable, asked to communicate at least once/week for 1 h | N=107. Able to endorse more than 1 diagnosis AN=62% (M), 49% (UM), BN=29% (M), 37% (UM), BED=10% (M), 16% (UM), EDNOS=41% (M), 35% (UM). Mostly female (statistics not reported), age 19–59 years (M=31, SD=8.94), 90.9% (M) and 88.6% (UM) Caucasian. SES not reported. | N=34 (30 recovered from an ED, 4 mental health professionals). Able to endorse more than 1 diagnosis–AN=56%, BN=38%, BED=15%, EDNOS=38%. 100% female, age M=34 years SD=12.88 (range not reported), ethnicity not reported for mentors but 81% Caucasian across entire sample (both mentee groups and mentors). SES not reported. | EDDS, EDQLS, questions about motivation, energy, & confidence towards recovery, treatment compliance, length of mentoring relationship and frequency of communication. | Impact of program–open-ended, qualitative only question. | Receive package of materials and assisted by an experienced mentor. Volunteer. | 1 year. |

| Ramjan et al. (2017) | Case Series | Adjunct to ED treatment. Mentoring program developed using Participatory Action Research. Content flexible, focused on promoting hope. Face-to-face and one-on-one for the majority of mentor and mentee pairings, one was email only due to social anxiety. | 10 | N/A | Variable–minimum 1 h/week contact, and at least 3 of meetings face-to-face. 13 weeks. | AN=7, BED=1, BN=1, OSFED=1. 100% female, age 20–42 (M=29.2, SD=8.2), ethnicity not reported, Paid work=54.5%, Work Hours/week M=34.5 (range 20–40). | N=10. Mostly recovered from AN, some BN (exact numbers not reported). 100% female, age 23–52 years (M= 28.9, SD=8.2), ethnicity and SES not reported. | Domain Specific Hope Scale, SF-12, EDQoL, K10, MCQ. | Domain Specific Hope Scale, SF-12, EDQoL, K10, MCQ. | Aside from initial PAR workshop, details of training/supervision and whether paid or volunteered not reported. | Recovered, average of 5 years, minimum requirement for recovery not reported. |

| Ramjan et al. (2018) | Case Series | Adjunct to ED treatment. Mentoring program using Participatory Action Research. Content flexible, focused on promoting hope. Face-to-face and one-on-one. | 6 | N/A | Variable. 13 weeks. | All AN. 100% female, 18–38 years (M=26.83, SD=7.8), ethnicity and SES not reported. | N=5. All AN. 100% female, age 20–44 years (M=30.4, SD=8.79), ethnicity and SES not reported. | SF-12, EDQoL, K10, MCQ, qualitative feedback. | SF-12, EDQoL, K10, MCQ, qualitative feedback. | Initial PAR workshop, monitoring of weekly logbooks–follow up phone or email support and supervision as needed. Online check in at 6 weeks. Costs reimbursed. Not reported whether mentors were paid or volunteered. | 5 years. |

| Ranzenhofer et al. (2020) | RCT | Adjunct to outpatient ED treatment. Randomized to peer mentoring, social support, or waitlist. Peer mentoring focused on the “Eight Keys to Recovery from an Eating Disorder” and use of recovery record. Social support mentoring focused on life outside the ED and was not focused on ED recovery. Face-to-face or videoconferencing depending on participant location. One-on-one. | 20 Peer Mentorship (PM) & 18 Social Support (SS) | 22 Waitlist (WL) | Variable. 1 h/week, 6 months | AN=13 (PM), 10 (SS), 10 (WL), AAN=2 (PM), 4 (SS), 6 (WL), BN=4 (PM), 3 (SS), 5 (WL), BED=1 (PM), 1 (SS), 1 (WL). Female 100% PM, 94.4% SS, 100% WL. | Number of mentors and demographic information not reported. PM in full recovery for a minimum 2 years and SS no lived experience of an ED. Minimum age 18. | BMI, EPSI, weekly binge and purge frequency, EDQLS, PHQ-9, STAI, health care utilization. | None. | Online training program (35 hours over 8 weeks), supervision every other week. Volunteer. | 2 years. |

| Age 14–45 years (M=27.9, SD=7.6 PM; M=31.0, SD=5.0 SS; M=27.1, SD=6.9 WL). White/Caucasian (75% PM, 94.4% SS, 91% WL). Private Insurance=55% (PM), 76% (SS), 88% (WL). | |||||||||||

| Rohrbach et al. (2022) | RCT | Randomized to online automated self-help program Featback, expert-patient support, Featback expert-patient support, or waitlist control. Participants able to seek help for ED but were not all necessarily in treatment. Online–Featback via website and email, expert-patient support via email or online chat. One-on-one. | 88 Featback (F), 87 Expert-Patient Support (EPS), 90 Featback +Expert-Patient Support (F + EPS). | 90 Waiting List (WL) | 8–20 min weekly for EPS and F + EPS | Whole sample–222/355 officially diagnosed with an ED, 91 no diagnosis but ED likely, 42 eating problems but ED unlikely (rates across groups similar). Female 93.2% F, 96.6% EPS, 98.9% F + EPS, 97.8% WL. Age M =28 SD=1.7 F, M=26.8, SD=9.4 EPS, M=28.3 SD=10.4 F + EPS, M=28.1 SD=12.4 WL. Dutch 88.6% F, 92% EPS, 88.9% F + EPS, 90% WL, Education Status Low=5.6% F, 13.7% EPS, 13.3% F + EPS, 20.5% WL, Middle=37.5% F, 39% EPS, 34.4% F + EPS, 39.3% WL, High=56.8% F, 47.1% EPS, 52.2% F + EPS, 40.4% WL. | N=5, required to be recovered, no other details reported. | EDE-Q, PHQ-4, GSES, SSL-12-I, RSES, IOS, questions re motivation, satisfaction, help seeking. | None. | 1 day training + intervention protocol provided, monthly supervision, paid. | Recovered, duration not reported. |

| Steinberg et al. (2022) | Case Series | Augmented FBT–peer mentor and family mentor included in treatment team. Peer mentor role model for recovery to inspire hope and motivation. Family mentor offered support, sharing of skills and strategies, and validation. Virtual. One-on-one. | 210 | N/A | Weekly, 50-minute sessions. Variable, up to 12 months. | AN 80%, ARFID 14%, BED 2%, BN 1%, OSFED 2%. Cisgender female 83%. Age M=16.1 (SD=2.87). White 71%, Payor: Health insurance=66%, private pay=3%, Other=27%. | Number of mentors and demographic information not reported. | Weight, EDE-QS, NIAS, PHQ-9, GAD-7, BAS, PVED, 1 question of treatment acceptability/satisfaction. | None. | 90-h training program, supervision (unknown frequency and with whom), certification. Not reported whether mentors paid or volunteered. | 2 years (for both peer mentors + family mentors [recovery criteria for their loved one]). |

Intervention Type

Mentee Outcomes

Participatory action research.

Flexible content programs.

Structured programs.

Augmented FBT.

Mentor Outcomes

Study Quality Assessment

Discussion

Impact on Mentees

Engagement and acceptance of lived experience mentoring.

Mentor Outcomes

Training and supervision of mentors.

Payment of mentors.

Research Quality, Limitations, and Future Directions

Conclusions

Footnotes

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Keywords

Authors

Competing Interests

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).