Depression is known to adversely affect male and female sexual functioning,

1,2 and depressive illnesses are more common in women than men.

3 The negative effect of depression on sexual functioning has been more extensively studied in women than in men.

4–8Data are limited concerning the sexual functioning of depressed men before antidepressant treatment.

9 Estimates

10 have come from patient reports, the outcomes of self-report, or physician interview rating scales. Although there have been some studies on erectile dysfunction and the effect of depression on erectile ability,

11–14 there has been a paucity of information concerning other sexual functions, such as desire and orgasm, in men with depression.

15 Many of these prevalence estimates have been confounded, in that they are more concerned with the construction and validation of a rating instrument to measure sexual dysfunction in men than in reporting the data regarding the symptoms in depressed men. Also, it has been argued that the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria should not be used to assess sexual dysfunction in depressed patients, so there have been limited reports of DSM-IV diagnoses in men with depression.

16Clayton et al.

17 reported that depressed men had significantly more sexual dysfunction than medical students, as measured by the Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ).

18 Total score and the domains of sexual desire/frequency, sexual pleasure, sexual desire/interest, sexual arousal, and sexual orgasm were all adversely affected by depression. The sexual functioning scores of depressed men, however, were better than those of depressed women. The small number of depressed patients in this study (fewer than 20 per group) precluded more detailed descriptions and comparisons of results. Howell et al.

7 reported, in an age-matched population of 20 healthy men and 26 depressed men, that depressed men had lower sexual interest and lower sexual satisfaction. Kennedy et al.,

9 in a study of 55 depressed men, reported that 40% had lower sexual interest, and 40% had decreased arousal, whereas reduced orgasm was found in only 15%−20% of depressed men. Bonierbale et al.

6 reported the results of a large population of depressed patients in France. The results, however, are confounded by the fact that 64% of the patients were already taking antidepressant medications. Furthermore, many of their patients had concomitant medical illnesses. Their results in men indicated greater prevalence of problems with libido (60%), erection (45%), and frequency (40%), than orgasm (20%).

Kennedy

9 claimed no difference between the effects of different types of depression on sexual dysfunction. In the last few years, considerable attention

19–22 has been given to Atypical Depression, which, in reality, is the most common type of depression, in over 40% of depressed individuals. Atypical Depression is characterized by reverse vegetative symptoms (overeating and oversleeping) and interpersonal-rejection sensitivity. More importantly, subjects with Atypical Depression retain mood reactivity; that is, their mood improves in response to positive life events. This characteristic might suggest different effects on sexual dysfunction.

The objective of this report is to describe further the prevalence of sexual dysfunction occurring in men with depressive illnesses. We examined 591 depressed men in five short-term (8-week) studies, two studies in patients with Atypical Depression, and three in patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), and assessed the effect of depression on sexual functioning as measured by DSM-IV criteria

23 at baseline, by the DeRogatis Inventory of Sexual Function (DISF), or by the DISF Self-Report Version (DISF–SR).

24Objectives

The study objectives were the following: 1) to study the prevalence of DSM-IV sexual dysfunction diagnoses in an untreated population of depressed men; 2) to study the prevalence of sexual dysfunction diagnoses by DISF criteria (i.e., at least 1 standard deviation [SD] below normative means) for total scores and domain scores in this population; 3) to study the effect of type of depression: Atypical Depression or MDD, on sexual functioning; and 4) to study the effect of severity of depression on sexual functioning.

The effect of MDD on sexual functioning in female subjects in these studies is described in a separate publication.

25 A comparison of the results presented here with those reported in women was not an objective.

Methods

There were only five double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of the drug gepirone–ER in the Phase III MDD investigations in which sexual functioning was measured (The original studies were conducted and funded by Organon. The data analysis and report writing was done by Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals: 134001, 134002, 134004, 134006, and 134017). In three studies (134001, 134002, and 134017), total N=345, the target population had MDD by DSM-IV criteria; in the other two studies (134004 and 134006), total N=246, the target population was major depression with atypical features (atypical depressive disorder, Atypical Depression) by DSM-IV criteria. Entry criteria for the MDD and Atypical Depression studies were essentially the same, with the exception that, for the Atypical Depression studies (134004 and 134006), symptoms of Atypical Depression were required. Also, studies 134001 and 134002 had a minimum Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, 17-item (Ham-D−17) of 20 as an entry criterion. Studies 134004 and 134006 did not have a minimum Ham-D−17 entry score. Study 134017 had a minimum entry score of 22 on the Ham-D−17.

The studies were conducted from 1999 to 2004 in 32 U.S. research sites. At each site, there was a primary psychiatrist and one back-up psychiatrist responsible for evaluations. Before any study-related activity, each subject signed an informed consent document that had been approved by an Institutional Review Board. The trials were conducted in compliance with the current revision of the Declaration of Helsinki, International Committee on Harmonization (ICH) guidelines and Good Clinical Practice (GCP), and current regulatory requirements. Before the inception of each of the five studies, investigator meetings were held, during which specific training sessions were conducted with the psychiatrists and auxiliary staff to ensure that they could adequately evaluate sexual functioning. Successful passage of a post-training test was required. However, a validation study of the DSM-IV diagnoses was not performed, nor was a structured interview scale used.

In three studies (134004, 134006, and 134017), at baseline, before any treatment, formal DSM-IV criteria Sexual Dysfunction diagnoses were made by a psychiatrist trained to evaluate sexual dysfunction: two studies of Atypical Depression (134004 and 134006; N=246) and one study of MDD (134017; N=180). Since all patients met DSM-IV criteria for MDD, this excluded them from a DSM-IV diagnosis of Sexual Dysfunction by Criterion C. Therefore, only criteria A and B were used. At baseline, DISF–SR was also collected in two MDD studies (134001 and 134002; N=91). DISF was also collected in two Atypical Depression studies (134004 and 134006; N=235).

Inclusion criteria for the studies of MDD were patients who met criteria for MDD by DSM-IV criteria,

23 with Ham-D−17

26 total scores ≥20. Inclusion criteria for the studies of Atypical Depression were patients that met criteria for DSM-IV criteria for MDD and the Atypical Features specifier.

27 To fulfill Atypical Depression criteria, patients had to maintain mood reactivity while depressed and have at least two of the following features: longstanding interpersonal-rejection sensitivity, weight gain/increased appetite, hypersomnia, and leaden paralysis. Patients with bipolar disorder were excluded. Baseline assessment included psychiatric evaluation, physical, clinical laboratory, and EKG evaluations.

28 The exclusion criteria required that subjects be off all psychotropic medications for 2 weeks for most antidepressants and other psychotropic drugs and 4 weeks for fluoxetine before the baseline evaluation. Subjects with a history of clinically meaningful medical illness, abnormal laboratory tests, or electrocardiograms, history of other psychiatric illness, or taking most concomitant medications, were excluded.

The DISF has been normed in the general population for both men and women separately. No adjustment was made for age, although the mean age was similar to the populations reported here.

29 In this report, a threshold of 1 standard deviation (SD) below the normative mean for the total score and each of the domains has been used as a criterion for caseness in regard to diagnosis of sexual dysfunction. To confirm the usefulness of this cut-off, the means for patients above and below the 1-SD level were compared.

Study Samples

The data and analyses presented here represent only the male samples of these studies and only the data from the baseline assessment, before any treatment.

The sample of depressed men for these studies is the all-subjects-treated population, that is, all subjects that were screened and for which there were either DSM-IV or DISF data. The all-subjects-treated population was selected because all patients had laboratory or physical exam reports. The numbers of patients for these studies are shown in

Table 1.

The total number of data entries for each individual analysis may differ slightly from that above because only patients for whom there are appropriate data for the selected parameter are included in a given analysis, and data for some subjects were not collected. Moreover, there is a different intent-to-treat population for the analysis of different parameters, creating a situation where the numbers do not always add up to the numbers presented above.

Study Data

To achieve the specific objectives of the study, the following results were obtained from analysis of baseline data: 1) the prevalence of DSM-IV sexual dysfunction diagnoses, that is, the number of DSM-IV sexual dysfunction diagnoses per total population; 2) comparison of DISF total score and domain scores in this depressed male population with those of a normed population; 3) the prevalence of sexual dysfunction defined as patients at least 1 SD below the norm on the DISF total score and domain; 4) analysis of the effect of severity of depression on sexual functioning, that is, the DISF total score and domain scores for each segment of the depressed population: mild, moderate, severe, and extreme, based on Ham-D−17 scores; 5) analysis of the effect of type of depression (MDD or Atypical Depression) on the total DISF score; and 6) comparison of DISF total scores corrected for depression severity in MDD versus Atypical Depression patients.

Statistical Analyses

These studies were not powered for analyses of sexual dysfunction, so that the minimum sample size required to detect a significant difference between sexual function parameters was not planned for. The data for DSM-IV diagnoses of sexual functioning are presented using the all-subjects-treated population. The categorical data were compared by the JMP−7.02 Program for odds ratio (OR).

Patient-level data from the four studies with the DISF data were combined to create a single data-set, from which DISF scores were calculated and compared by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) from the SAS database by a JMP−7.02 Program, with the means compared by t-test.

Results

Demographics

The demographic parameters of the populations are shown in

Table 1. The demographics for the pool of patients for DISF analyses and DSM-IV analyses are similar. This male population is white (80%), with an average age of about 39 years (range: 18–69). Most (54%) had a chronic illness of exacerbations and remissions, with the average age at their first experience of depression, 26 years. The average length of the current depressive episode was over 1 year (51%), and 65% had previously taken antidepressants. Atypical Depression patients differed from MDD patients in two respects: The onset of illness was earlier in Atypical Depression patients, 24.6 (11.6), compared with MDD, 27.1 (11.7 years [p=0.044]), and the duration of the present illness >1 year is more common in Atypical Depression patients, 57%, than in MDD patients, 46% (p=0.006).

The average Ham-D−17 scores at baseline are also shown in

Table 1. Values for the one Ham-D Sexual Functioning item (Question 3) ranged between 0.80 and 1.02. There were no significant differences for any comparison.

Prevalence of DSM-IV Criteria A and B for Sexual Functioning Diagnoses

For the pool of three studies in which the DSM-IV diagnoses of Sexual Disorders were evaluated on all patients at baseline, the results are shown in

Table 2. For the three studies combined, most prevalent was hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), at 8.0%, followed by erectile dysfunction, 7.3%, and orgasmic disorder, 3.6%. There were large, statistically significant, differences between patients with MDD and Atypical Depression, especially with regard to erectile dysfunction: 2.8% in MDD, 10.6% in Atypical Depression (p=0.002); and male orgasmic disorder, absent in MDD, 6.1% in Atypical Depression (p=0.021). Total patient scores are within the literature estimates for the normal population, except for premature ejaculation which is low. For the Atypical Depression population, erectile dysfunction is higher than the literature estimate.

Baseline DISF Scores in Depressed Men

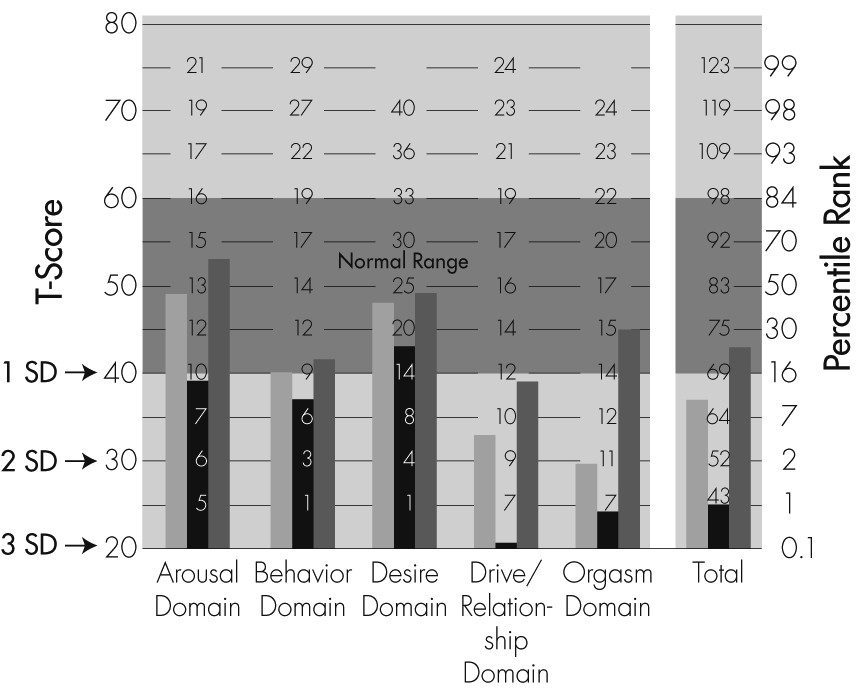

For the four studies in which the DISF was measured, two in patients with MDD and two in patients with Atypical Depression, the results are shown in

Table 3. The data are compared with the results from a non-patient, community population. The 50th percentile represents the mean score of the normed population (

Figure 1).

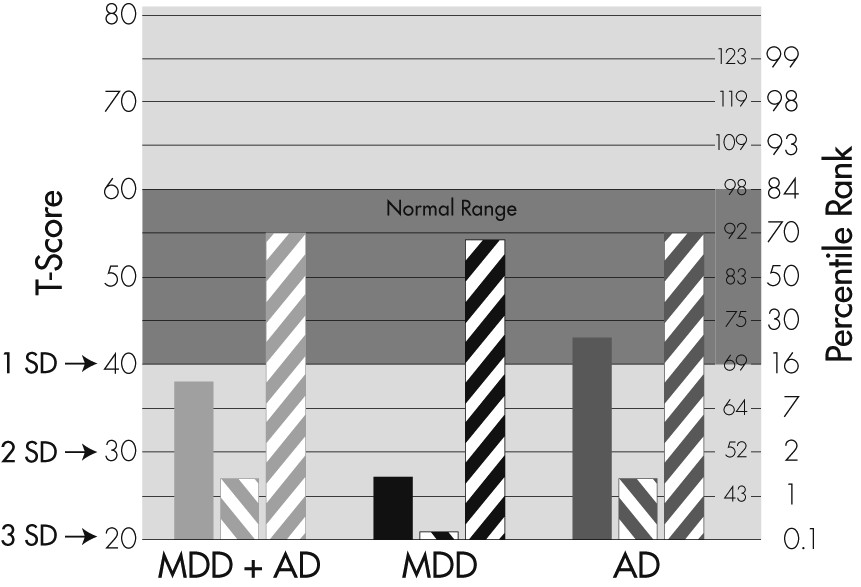

29 As compared with the norm, the all-subjects mean DISF total score is very low, at the 14th percentile. There is a difference between subjects with MDD (1st percentile) and Atypical Depression (25th percentile) that is statistically significant, at p <0.0001. The MDD total score is more than 2 SDs below normal, whereas the Atypical Depression score is within the normal range.

The effect of depression on the domains of the all subjects’ DISF scores differs according to the specific domain: orgasm (2nd percentile) and sexual drive/relationships (5th percentile) are most affected, whereas sexual behavior/experience (18th percentile) is at the lower limit of the normal range. Sexual desire (45th percentile) and sexual arousal (51st percentile) are less affected by depression. For each domain, the differences between MDD and Atypical Depression subjects are highly statistically significant (p <0.005), with results for MDD lower than those for Atypical Depression. Atypical Depression domain scores for arousal, behavior, and desire, are well within the normal range, and drive is close to the normal range. For MDD, the domain scores for drive/relationships and orgasm are 2–3 SDs below the mean of a non-patient population.

A graphic representation of the mean DISF Scores is presented in

Figure 1. The normal range represents the mean, plus-or-minus 1 SD, for the normed population. To better understand the substantive aspects of this report, area T-scores are normalized, standardized scores derived from a community population free of any stated sexual dysfunction.

29 In terms of T-scores, a T-score of 50 represents the mean, with an SD of 10. This means a difference of 10 from the mean indicates a difference of 1 SD. Thus, a T-score of 60 is 1 SD above the mean, whereas a T-score of 30 is 2 SDs below the mean, and a T-score of 20 is 3 SDs below the mean.

Prevalence Rates of Sexual Dysfunction

DISF Criterion of 1 SD Below Normed Mean

To test the usefulness of this criterion as a discriminator of sexual dysfunction, the DISF scores for those patients at least 1 SD below the mean were compared with those above that cut-off threshold. Applying this diagnostic criterion gives the results found in

Figure 2 and

Data Supplement Table 1 (online).

For the DISF total score, the groups above the −1 SD threshold are all within the normal range at or above the normal population mean, whereas the scores for those patients below the 1-SD cut-off threshold are at or below the 1st percentile of the normal population. The differences in DISF scores between the above and below −1 SD groups are all highly statistically significant. Thus, the diagnostic cut-off threshold of 1 SD effectively divided patients into those with sexual dysfunction and those without.

Each of the DISF domains have essentially the same type of data as those of the DISF total score; that is, the mean values above and below the −1 SD cut-off threshold are highly significantly different, with p <0.0001. Tables containing the data for DISF domains of arousal, behavior, desire (cognition/fantasy), drive/relationship, and orgasm are found in

Data Supplement Tables 1–6 (online).

DISF Criteria Prevalence Rates

For DISF total score of the combined MDD and Atypical Depression patients, using the criterion of at least 1 SD criterion, the prevalence rate is 55%; that is, more than half of the patients have sexual dysfunction (

Table 4). For MDD patients, the prevalence is higher, at 75%, as compared with 47% for Atypical Depression (p <0.0001). For the MDD+Atypical Depression sample, DISF domains are not all affected equally, with drive (63%) and orgasm (67%) being most affected, and desire (24%) being less affected. For each of the domains, the results for MDD are worse than for Atypical Depression, and the differences between Atypical Depression and MDD are all statistically significant, at p <0.05 or better. For MDD patients, drive and relationships (98%) and orgasm (84%) are severely impaired.

Comparison of Ham-D–17 Baseline Scores in Patients Who Score Above and Below the DISF Total Score (1 SD Lower-Limit Cut-Off Threshold)

The Ham-D−17 baseline score for the DISF total score group above the lower-limit cut-off threshold of 1 SD is 21.0, and that for the group above the threshold is 18.8. These scores are significantly different, at p <0.0001. Comparison of Ham-D−17 baseline scores for all of the DISF domains shows the same highly significant differences. These results suggest that increased depression is a factor in determining severity of sexual dysfunction. The data are found in

Data Supplement Tables 1–6 (online).

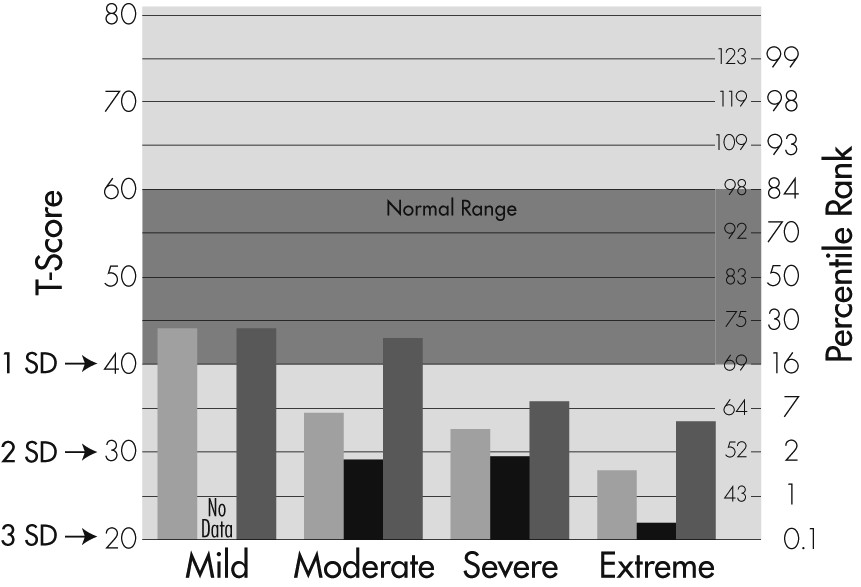

Effect of Severity of Depression on Sexual Functioning

A sample of 326 male patients enrolled in the four studies in which the DISF was used was partitioned by Ham-D−17 entry score into four severity groups: Mild (<18), Moderate (19–22), Severe (23–25), and Extreme (26–33). The severity classifications were selected to be consistent with those utilized by Muller et al.

30 The DISF total scores and domain scores were calculated for these four depression-severity groups. The results for DISF total score are shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 5.

The more severe the depression as measured by higher Ham-D−17 entry total scores, the lower the DISF total and domain scores, indicating decreased sexual functioning. The results for DISF total score show that each level of depression has DISF mean scores that were statistically different from each other level, except for the differences from Moderate to Severe and Severe to Extreme. For the MDD+Atypical Depression group, the mean values for Mild versus Moderate, Severe, and Extreme are different, p=0.004, p <0.0001, and p <0.0001, respectively, and for Moderate versus Extreme, p=0.020.

The results for the desire and orgasm domains follow the same pattern: the more severe the depression, the lower (worse) the DISF domain scores. The effect on orgasm is more pronounced that that on desire. For the desire domain, each level of severity of depression produces DISF domain scores statistically different from each other, except the difference between Moderate and Severe. Severity of depression affects both MDD and Atypical Depression patients, although Atypical Depression scores are higher (less sexual dysfunction) at almost every level of depression.

Tables containing similar data for DISF domains of arousal, behavior, desire (cognition/fantasy), drive/relationship, and orgasm are found in

Data Supplement Tables 7–11, respectively (online).

Comparison of DISF Total Scores Corrected for Severity of Depression in MDD and Atypical Depression Patients

Table 5 compares the sexual dysfunction of Atypical Depression and MDD subjects. The results indicated that for the MDD group, DISF average score was 47.9, whereas the Atypical Depression average score was 71.7. This result is statistically significant (p <0.0001). However, the average Ham-D−17 scores for these two subject groups are also different: MDD, 23.0 (2.6) and Atypical Depression, 18.6 (4.0). The patients with MDD had more severe depression; since more severe sexual dysfunction can occur with increased depression alone, it is unclear whether the type of depression alone has an effect on the results for sexual dysfunction.

Discussion

Characteristics of This Depressed Male Population

In this United States population, the depressed men were young (average age: 39 years; range: 18–69 years), free of antidepressant medication, and not suffering from diabetes or cardiovascular disease. The presence of sexual dysfunction was not an entry criterion for any of these studies. Each of the 32 individual sites was situated around the United States, and the data represents a cross-section. Approximately 15% of patients screened for these studies were not included in this database because they were excluded for medical and concomitant medication reasons. Addition of these patients would probably have increased sexual dysfunction prevalence rates.

Additional data from each of these subjects, such as the quality of sexual functioning before depression, the reaction of the subject’s partner to depressive symptoms, the role of sexual dysfunction in the development of the depressive illness, and so forth, would have been useful. These data were not obtained. What is described here is the association of sexual dysfunction with depressive illnesses, without implication of cause and effect.

Rating Scales and Clinical Evaluations

The baseline data of the DSM-IV diagnoses and the DISF scores give an opportunity to characterize the effect of depression on this male population. The percent of depressed subjects meeting criteria for sexual dysfunction by DSM-IV criteria is small and in the range of that reported for the (non-depressed) normal population.

31 Although the DSM-IV does not recommend making sexual dysfunction diagnoses on subjects with MDD, the objective of this study was to describe the sexual disorders that occur in men with depression. Furthermore, DSM-IV diagnoses allow evaluation of erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation, conditions that are most often evaluated. The outcome of very low numbers indicates that DSM-IV criteria are not a productive way of describing sexual disorders in a depressed population.

Since the DISF has been normed to the general population, scores from depressed men could be compared with that of normal men. Scores of 1 SD below the normed mean essentially divides the depressed men into two populations, one that is in the normal range, and the other which is far below the normal range. For the total score and each of the domains, the results for the two populations are highly statistically significantly different.

Classifying sexual dysfunction by the criterion of 1 SD below the normed average value for the DISF provides a totally different view of the sexual disorders in depressed men from that of the DSM-IV. The results with DISF criteria are 4–20 times greater than for those diagnosed with DSM-IV criteria. For total score indicating any sexual dysfunction, 55% of subjects met criteria for sexual dysfunction. This is consistent with what has been observed clinically with depressed men.

One obvious reason why there are differences between DSM-IV and DISF results is that, for DSM-IV diagnoses, there is a requirement for marked distress or interpersonal difficulties. Perhaps because of the depressive illness, these men either did not have or refused to admit distress or interpersonal difficulties. These two methods of assessing sexual functioning are measuring two different constructs.

Not only does the magnitude of the effect differ between the two methods of patient assessment, but the predominant area of sexual dysfunction also differs. For DSM-IV, desire and arousal are most affected by depression. This agrees with previous studies.

7,9,16 However, in the DISF results, it is clear that orgasm and drive/relationships are most affected by depression, and that desire (cognition/ fantasy) and arousal are somewhat spared. Although these results differ from what has been reported for men, they are consistent with what has been reported for women.

25 The differences reported here might also have to do with the severity of depression. Although the cut-off was −1 SD from the norm, the average for this group of men was −3 SDs below the norm. Furthermore, desire and arousal are what is expected of men, and these men may be less willing to admit these problems in an interview situation than on a rating scale. Finally, it may be possible that the way in which the questions were asked in the DISF might skew the results.

Subtypes of Depression

Two samples of depressed subjects were studied: MDD and Atypical Depression. Studies have shown that Atypical Depression is a commonly-seen type of depression found in clinical settings.

19,20 The sample of Atypical Depression patients in the present study was younger at first onset of depressive illness, and their current episode of depression was longer in duration than the MDD subjects. The average Ham-D−17 score in the Atypical Depression group is less than that of the MDD group. These findings are consistent with the results of others.

Analysis of both DSM-IV diagnoses and DISF scores indicate that the Atypical Depression group had less sexual dysfunction than the MDD group. These results differ from those of Kennedy et al.,

9 who claimed no difference in sexual dysfunction among various depression subtypes. The question then becomes, since there is significant difference in levels of depression between the two groups, is the observed difference in sexual dysfunction due to the type of depression or the severity of depression? At this point the answer is unclear.

Also, why a difference should occur is not known. There are reports of different neuroreceptor abnormalities between Atypical Depression and MDD patients.

32 Possibly the mere presence of mood reactivity in Atypical Depression subjects may protect them somewhat from sexual dysfunction.

The literature has also been inconsistent on the effect of severity of depression on sexual functioning. However, the results here are comparable to those of Bonierbale et al.,

4 who measured depression with the MADRS. For a given level of severity of depression, MADRS scores are slightly higher than Ham-D−17 scores.

33 Bonierbale et al.’s classifications of mild, moderate, and severe are comparable to those using the Ham-D−17 scores here. Bonierbale et al. did not have an Extreme category. The difference between these results and others such as Kennedy et al.

9 may be related to differences in populations and different measures of sexual dysfunction and depression.

The cut-off of −1 SD on DISF total score divides the population in two. There is a statistically significant difference between the Ham-D−17 scores of the Above and Below groups (p <0.0001), indicating that a major factor causing men with depression to fall into the sexual dysfunction group is severity of depression.

The lack of a placebo group of subjects with no depressive illness detracts from the generalizability of these results, although the group of patients with mild depression is interesting. This Mild group has an average Ham-D−17 score of 15.8. In some studies, a Ham-D−17 of more than 16 (or the equivalent on a different rating scale) will allow inclusion of a subject into a study, assuming that with a Ham-D−17 score below 16, depression criteria are not met. The data presented here suggest that, even at <16, there is significant sexual dysfunction related to depression, and this group would not serve as a control group. A control group would need to have even fewer symptoms of depression.

It has been reported that low testosterone levels cause antidepressants to be ineffective,

34,35 and low testosterone levels are associated with sexual dysfunction.

36,37 In future studies, testosterone levels should be correlated with depression and also correlated with the efficacy of drugs intended to treat sexual dysfunction in men.

There is much written about the effects of depression and sexual dysfunction on quality of life. This combination has been associated with suicide in previous research.

38 There is no question that whether the depressed patients initially recognize sexual dysfunction symptoms or not, treatment of sexual dysfunction should be a part of the treatment of depression. Medications with both antidepressant and pro-sexual effects need to be developed and made available.

Conclusions

DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (A and B) for determining sexual dysfunction do not appear to be sensitive in men with major depression. The DISF criterion of at least 1 SD below the mean as an operational criterion for determining sexual dysfunction does a better job of dividing the depressed population into those with sexual dysfunction and those without. Men with Atypical Depression have less sexual dysfunction than men with MDD. This is true for DSM-IV diagnoses and total DISF score, and for each of the various domains of sexual functioning. These differences appear to be both statistically and clinically significant. The DISF domains of orgasm and drive are more severely affected by depression than are desire and arousal.

Severity of depression is clearly correlated with severity of sexual dysfunction. To a large extent, it appears that whether or not depressed men have sexual dysfunction is determined by the severity of their depression. However, type of depression may make a difference, as well.