Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is marked by recurring intrusive thoughts (i.e., obsessions) and ritualistic behaviors (i.e., compulsions) aimed at reducing distress. Its 12-month prevalence is approximately 1.2% in the United States,

1 with annual incidence of 0.55 per 1,000 person-years.

2 OCD can be quite debilitating, with significant impairment in functioning and quality of life.

3,4 The disorder generally improves after evidence-based psychological and/or pharmacological interventions, including exposure and response prevention (ERP), serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs), and ERP combined with SRIs.

5 Several medications may be combined with SRIs in efforts to augment benefit.

6Patients with “intractable” OCD remain very severely ill and impaired despite first- and second-line treatments. For them, neurosurgery (stereotactic ablation or deep brain stimulation [DBS]) may be an option. Both kinds of procedures alter activity in neural networks implicated in the illness. DBS, in contrast to ablation, is generally reversible.

7 Given the significant risks and burdens imposed by either approach, prospective patients must meet high eligibility thresholds. Estimates of how many OCD sufferers are surgical candidates vary widely, as indicated by recent controversy over FDA humanitarian approval (a Humanitarian Device Exemption, or HDE) of deep brain stimulation for OCD.

8,9 The HDE is intended for conditions where adequately-powered, randomized, controlled trials are not feasible, given the small number of patients affected. Fins and colleagues

9 suggested that the number of candidates for DBS for OCD may be as high as 20%−30% of total cases and that the HDE was therefore misused. The FDA’s HDE approval suggests drastically lower rates, given its statutory limitation to conditions affecting fewer than 4,000 people in the U.S. annually. A high estimate of the affected population is also discordant with the number of annual procedures reported in Belgium (0.6 per million inhabitants).

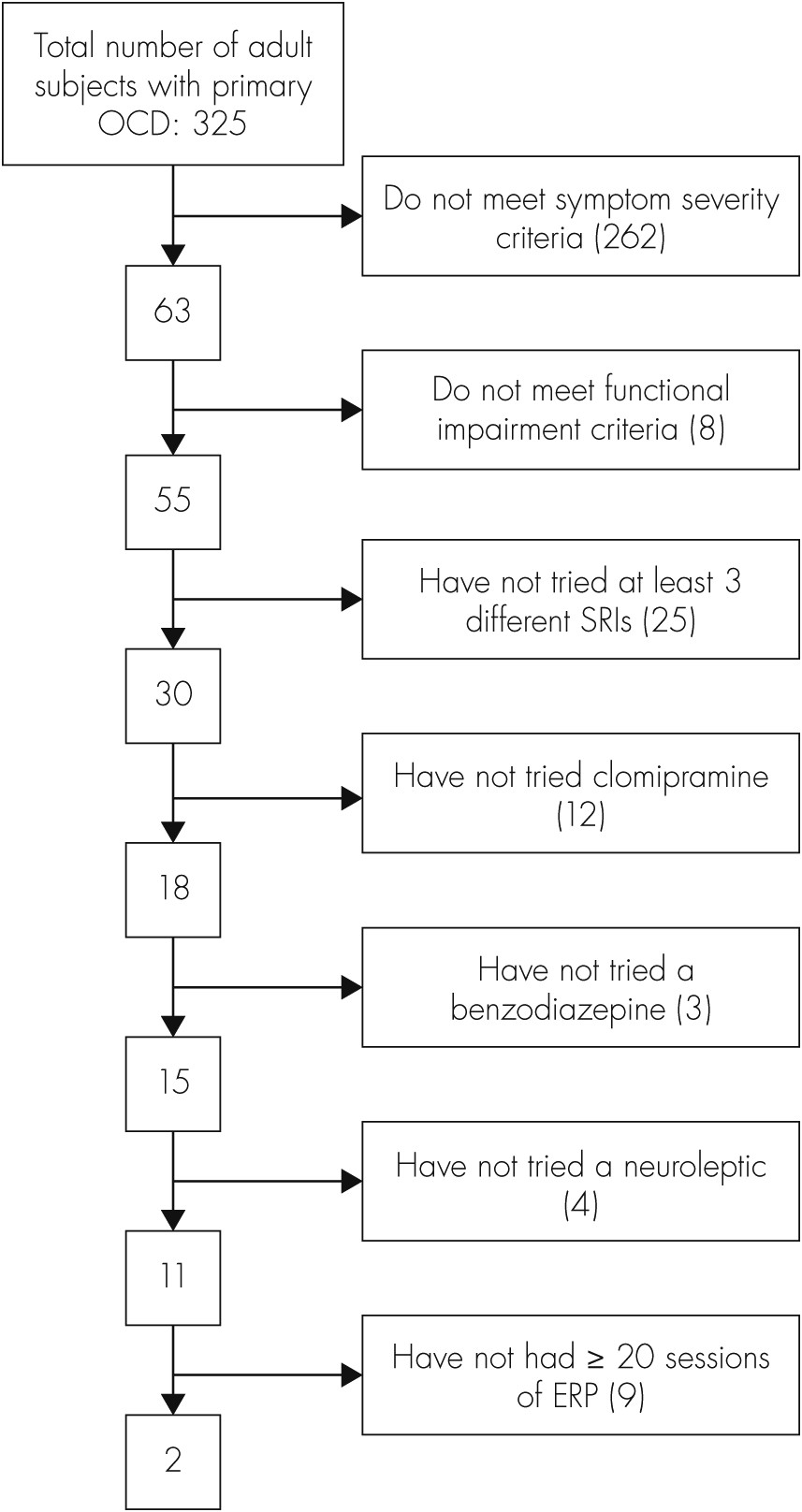

10 To derive a realistic estimate of the relevant population, we systematically applied DBS selection criteria to a well-characterized naturalistic clinical sample.

Discussion

Meeting the stringent criteria to qualify for DBS is rare among the general OCD population. Considering incidence rates for OCD (0.55 per 1,000 person-years),

2 12-month prevalence rates (1.2% of the U.S. population),

1 and the fact that only approximately 25% of people with OCD seek treatment for this disorder,

4,18 our findings suggest that the pool of potential surgical candidates is extremely small. Using these values, we estimate the number of DBS candidates to be in the range of 184–4,020 patients per year, depending on whether yearly incidence or prevalence is considered, respectively (based on the 2010 U.S. population of individuals age 18–79).

19 However, this estimate should be interpreted with reasonable caution because DBS candidacy is clearly a low base-rate event. Based on our findings, previous estimates

9 suggesting that 20%−30% of all OCD patients could be surgery candidates appear more consistent with the percentage of OCD patients with severe symptoms; however, as is apparent in the present study, the presence of severe symptoms is a

necessary, but

not sufficient condition for candidacy for neurosurgical intervention.

Although quite low, the final number of eligible candidates from the present analysis still may be an overestimate. When exact surgery criteria could not be replicated from available data, criteria used erred on the side of inclusion whenever possible so as not to underestimate the number of potential candidates. Also, while we examined some entry criteria here, others could not be included because of insufficient information: comorbid neurological or other relevant disorders, whether psychiatric medications were prescribed at high-therapeutic doses, general health, acute suicidality, etc. Applying these criteria may have further reduced the number of potential candidates. Also, the sample used is, in all likelihood, biased, since half-or-more of the patients had been treated in a well-known OCD specialty clinic, which they may have sought out because of the severity of their symptoms or failures of previous treatments. Although a limitation of the current study, it probably increases the likelihood of having participants who meet criteria for DBS by virtue of severity, impairment, and their likelihood of having received adequate conventional treatments. Another potential limitation is that participation in the BLOCS sample required willingness to participate in annual interviews, which may have excluded some of the more impaired participants.

In our research group’s experience with independent reviews of patients’ qualification for inclusion in our DBS controlled trial, questions from reviewers most commonly focus on adequacy of past ERP attempts. ERP is highly efficacious and generally considered as a first-line treatment for OCD.

5 Before labeling a case “intractable,” it is essential to ensure that adequate trials of ERP with a well-qualified therapist were conducted without substantial benefit. In our experience, patients qualifying for DBS typically exceed the minimum requirements for previous ERP trials.

However, our analysis highlights an underutilization of efficacious treatments. Most severely affected individuals had not tried a sufficient variety of medications to have pharmacotherapy ruled out as a potentially effective option. Similarly, as has been previously noted in this sample and others,

20–22 behavioral psychotherapies are often underutilized in the treatment of OCD and other anxiety disorders. This is especially worrisome, as ERP is a highly-efficacious first-line treatment for OCD, with or without concurrent SRIs.

6 Previous work examining utilization of cognitive-behavioral therapy within the BLOCS sample has suggested a variety of reasons for this underutilization, including financial cost of treatment, fear of treatment, difficulty attending sessions, and lack of clinician recommendation.

20 Barriers to receipt of efficacious treatments need to be addressed, as certainly some of the patients in the present study would be expected to benefit from additional treatments.

In this study, 53 of the 55 participants met severity and impairment cutoffs, but had not exhausted all treatment options. We are, of course, unable to predict outcomes for these patients if additional treatment options were aggressively pursued. Similarly, the reasons why additional treatments had not been pursued in these cases (e.g., client or clinician decision, accessibility of treatment, etc.) remain unknown. Given that many of these treatment approaches, particularly behavior therapy, are highly efficacious, at least some of these patients would be expected to improve, although the number remaining severe under these hypothetical circumstances cannot be reasonably anticipated. Prospective longitudinal studies are required to answer questions about outcomes for such patients.

Given the very small population of OCD patients who receive neurosurgical interventions, it is premature to put forth specific recommendations for improving identification of optimal DBS candidates. It has been difficult to characterize this small group, and even more difficult to begin to identify characteristics of those candidates most likely to benefit from these treatments. Although it is too early to say which characteristics may typify optimal DBS candidates, we can recommend several lines of research that will serve to better characterize intractable OCD populations, as well as those who may respond well to DBS versus alternative interventions. First, investigations into the course of treatment-refractory OCD are needed to establish the stability of severe OCD over time; longitudinal studies may also play an important role in delineating the burden of illness despite aggressive treatments. Second, when sample sizes permit, investigations of neurosurgical and other interventions for intractable OCD should seek to identify subgroups of patients who may respond differently to treatment. For example, some reports suggest that those with primary-incompleteness-type OCD may be less likely to respond to these treatments.

23 Third, the formation of a national/international registry of psychiatric neurosurgery cases would allow systematic collection of data, which may serve to further inform candidate selection and optimize patient outcomes for this small and unique group of patients.

24 Finally, more information is needed on viable alternatives to neurosurgical intervention, including intensive residential treatment programs. Although surgical candidates are typically encouraged to try residential treatment, and many have already tried and failed to benefit from these programs by the time they seek out neurosurgery, previous participation in a specialized residential treatment program is not currently a requirement for DBS. Additional information is needed to determine whether such programs may be a practical and effective alternative to neurosurgery for some candidates.

To maximize benefit and minimize risk for patients with intractable OCD, it is important to identify which neurosurgery inclusion/exclusion criteria should be retained and whether others should be added or discarded. Overly-inclusive criteria may be problematic by allowing nonoptimal cases to assume the risks associated with neurosurgery; however, other risks exist with overly-stringent criteria, such as risk of suicide while a patient is waiting for evaluation or told to try another intervention before qualifying for surgery.

10 Entry criteria for neurosurgery must continue to evolve, influenced by ongoing interdisciplinary research.

In part, refining selection criteria will depend on understanding more about the clinical features of this population, following the recommended lines of research above, as well as proposed biomarkers that may predict outcomes. Empirically evaluating existing criteria and attempts to refine these will require thorough systematic collection of longitudinal data in patients with disabling, highly-refractory OCD. Such studies should focus on both those who are and are not treated surgically in order to compare clinical characteristics, as well as outcomes. Regarding the narrower population of patients who do undergo surgical intervention, collecting systematic baseline and follow-up data on patients undergoing DBS and ablative surgeries targeting the same circuitry would be highly informative. The quality and type of data collected will also be paramount and should include not only information on symptom presentation and severity, but also patterns of comorbidity, core features of the illness, neuroimaging, neuropsychiatric functioning, and measures of observable behavior.