APA launched DSM-5 in May 2013.

1 In 2010, the APA ADHD and Disruptive Behavior Disorders Work Group (referred to hereafter as the DSM-5 Work Group) proposed changes to the criteria for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

DSM-IV ADHD criteria and the proposed DSM-5 criteria were not tested in field trials with adults.

2,3 We focus here on two of the 2010 proposed changes that substantially affect adults: 1) reducing the number of required symptoms from six to four in both ADHD dimensions (inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity) for adult patients and 2) the addition of four new impulsivity symptoms.

Previous investigations documented a normative decrease in ADHD symptoms across the life span in both clinical and community samples. Nevertheless, impairment resulting from the symptoms tends to persist,

4–6 even when the number of remaining symptoms is fewer than required to assign the diagnosis. Reducing the number of required symptoms to four (rather than six) in both ADHD dimensions has been proposed as more appropriate for adult patients, capturing a significant proportion of individuals with clinically relevant impairment from ADHD symptoms.

7–9 Considering this, the DSM-5 Work Group initially suggested a four-symptom cutoff on either list for assigning ADHD as a diagnosis for adults. Although this proposal was supported by previous research, it raised concerns about the possibility of artificially increasing false positives and the prevalence of the disorder.

10Another area of debate concerning the diagnosis of ADHD in adults is which set of symptoms best captures the clinical presentation of ADHD after childhood. It is not clear which DSM-IV ADHD symptoms are more robustly associated with the ADHD diagnosis or with clinical impairment. Concerns have been raised about whether relevant symptom groups that cause impairment for adults (e.g., executive dysfunction, emotional dysregulation, and impulsivity) are adequately captured in the existing symptom set.

11,12 To address such concerns, the DSM-5 Work Group initially suggested including four additional impulsivity symptoms to the already large list of ADHD symptoms to be tested in field trials. These symptoms were as follows: acts without thinking, is often impatient, is uncomfortable doing things slowly and systematically and often rushes through activities or tasks, and finds it difficult to resist temptations or opportunities, even if it means taking risks. The proposal of adding these new symptoms would raise the question of whether it would be better to 1) replace old with new symptoms to maintain a total of nine and thus avoid having more symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity than of inattention or 2) increase the total hyperactive/impulsive symptoms set length from nine to 13 items. In either event, the effects on internal and external validity would need evaluation.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the reliability and validity of the 2010 DSM-5 Work Group proposed modifications for ADHD criteria in adults in a clinical sample. Because reliability is a prerequisite to validity, we first examined test–retest reliability. We then addressed the following research questions. First, does the inclusion of four new impulsivity symptoms make a three-factor solution (allowing a better representation of impulsivity) a better fit for data than the traditional two-factor solution found with DSM-IV criteria? Second, are the proposed DSM-5 ADHD symptoms more specific for ADHD (versus comorbid psychiatric conditions)? Third, what set of DSM-5 ADHD symptoms best captures the clinical diagnosis of ADHD and/or impairment, and do the four new proposed impulsivity symptoms add value? Finally, what is the best number (cutoff point) of DSM-5 ADHD symptoms to identify impaired adults?

It is important to bear in mind that the DSM-5 Work Group proposed other modifications in ADHD criteria in 2010 that might affect adults, such as raising the age of onset criterion

13–15 and rewording the original 18 DSM-IV symptoms to make them more adequate for adults.

2 Thus, when using 2010 DSM-5 ADHD proposed criteria, we always required an age of onset before age 12 years and used the reworded symptoms. In addition, because of the rewording, we assessed the performance of all proposed DSM-5 symptoms, rather than only the four new ones.

Methods

Participants

The sample for this case-control study includes 133 participants: 68 patients seen in an ADHD outpatient clinic and assessed as having ADHD by DSM-IV criteria and 65 comparison participants (10 of which were outpatients without ADHD and 55 were non-ADHD control subjects).

A consecutive sample of 78 adults seeking treatment was evaluated for ADHD in the ADHD Outpatient Program at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (Porto Alegre, Brazil), from July to December 2011. Of these individuals, 10 did not meet DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD, leaving 68 subjects who were included in this study as the ADHD group. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) native Brazilians of European descent, 2) age ≥18 years, and 3) fulfillment of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD, both currently and during childhood. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) evidence of clinically significant neurologic diseases (e.g., delirium, dementia, epilepsy, head trauma, or multiple sclerosis) and 2) current or past history of psychosis. All measurements were performed after recruitment and before the initiation of treatment for ADHD.

The control sample comprised 65 subjects: 55 adults who were recruited at the blood bank of the same hospital and the 10 above-described ADHD-negative subjects. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same for controls as for cases, except for the absence of DSM-IV ADHD diagnosis. The University Hospital Institutional Review Board approved the project, and all subjects (ADHD cases and controls) provided written informed consent.

Assessment Procedures

All interviewers in this study were psychiatrists who had extensive training in the application of all of the instruments of the research protocol. The ADHD and control subjects were assessed using the same protocol.

The information about DSM-5 ADHD criteria was collected through a clinical interview, during which all symptoms were formulated exactly as written in the 2010 DSM-5 Work Group proposal and rated by the clinician as present or absent. To evaluate criteria stability over time, a reevaluation of DSM-5 ADHD criteria was performed in 18 ADHD cases 15 days after the first interview by the same psychiatrist who had previously interviewed the patient.

DSM-IV ADHD and oppositional-defiant disorder criteria were assessed using the Portuguese version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Epidemiological Version,

16 as usually applied for adolescents.

17 The severity of ADHD and oppositional-defiant disorder symptoms was assessed by the Brazilian version of the SNAP-IV Rating Scale,

18 in which the frequency of each DSM-IV symptom is rated from zero (not at all) to three (very much).

The diagnoses of conduct and antisocial personality disorders were assessed using the Portuguese version of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, a short semistructured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10 psychiatric disorders.

19 All other lifetime psychiatric disorders were assessed using the Portuguese version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (Research Version).

20Clinical impairment was measured by the Sheehan Disability Inventory,

21 a clinician-rated Likert scale from zero (not at all) to 10 (extremely), with items addressing the effect of symptoms on three areas of functioning: work, social, and family life. Impairment was defined as a score of ≥5 in any of the three dimensions, as previously suggested.

22All instrument-derived diagnoses were rechecked and confirmed by a clinical committee composed by the psychiatrist interviewers and the head of the staff (E.H.G.), as previously described.

23 The research protocol also included the assessment of demographic and educational data, medical history, and social problems.

Data Analytic Strategies

To test whether the ADHD sample in this study adequately represents our general ADHD outpatient clinic population, the ADHD cases in this study were compared with all other ADHD cases from the ADHD outpatient clinic in terms of demographic and clinical profiles using the two-proportion z test for categorical variables and the independent-samples t test for quantitative variables.

The test–retest reliability of DSM-5 ADHD symptoms was assessed with Cohen’s kappa coefficient calculation.

24To evaluate the change in clinical and demographic profiles with DSM-5 proposed criteria, we compared cases fulfilling DSM-IV criteria with additional cases that would only be identified after DSM-5 proposed criteria application (with a threshold of four of nine inattention symptoms and four of 13 hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms for the diagnosis). These independent groups were compared using the two-proportion z test for categorical variables and the two-sample t test for quantitative variables.

The factor structure of the ADHD symptoms was tested with confirmatory factor analysis solutions with two versus three correlated factors; this was done for the 18 DSM-IV symptoms as well as the 22 DSM-5 symptoms. This strategy examines whether the factor structure would change with the addition of the four new symptoms and whether a three-factor solution (with impulsivity emerging as a separate factor from hyperactivity) has a better fit when the four new symptoms are included than when they are not.

The performance of the proposed DSM-5 ADHD symptoms in predicting clinical DSM-IV ADHD diagnosis was tested to evaluate how well the symptoms conform to the DSM-IV definition of ADHD. This was done in a three-step approach. First, the bivariate association between individual DSM-5 symptoms and DSM-IV ADHD diagnosis (clinician derived) was assessed with odd ratios estimates, which allowed ranking the DSM-5 symptoms according to their unadjusted odds ratio related to DSM-IV ADHD diagnosis. At this point, the association between DSM-5 symptoms and other psychiatric disorders was also tested with the same statistics. Thus, for each DSM-5 item, the odds ratios of the associations with ADHD and with comorbidity could be compared.

After the initial bivariate step, a binary stepwise logistic regression model with forward entrance was performed, considering DSM-IV ADHD diagnosis as the dependent variable and all DSM-5 ADHD proposed symptoms as independent variables. This analysis allowed us to find how many and which DSM-5 symptoms are independently associated with DSM-IV ADHD diagnosis after controlling for the other DSM-5 symptoms.

In the third step, all possible subsets (APS) logistic regression analysis was used to confirm the set of DSM-5 symptoms that best predicted DSM-IV ADHD diagnosis. The APS analysis helps to select the best subset from a larger set of predictors. In such situations, different subsets might have almost equivalent associations with the outcome, and conventional stepwise regression analysis might select a suboptimal subset owing to minor differences in bivariate associations. The APS analysis protects against this problem because it generates results for a large number of different models with a fixed number of predictors, which was determined from the earlier stepwise logistic regression analysis. The APS analysis also ranks the best subsets according to their association with the outcome (using the chi-square as the ranking criterion). Once the ranking of subsets is known, the researcher can select the predictors that are more consistent across the top-ranked subsets. In our APS analyses, we strictly followed the procedures by Kessler et al.

12 to allow comparability of the findings.

The same three-step statistical approach was used to test the performance of the DSM-5 proposed symptoms in predicting clinical impairment.

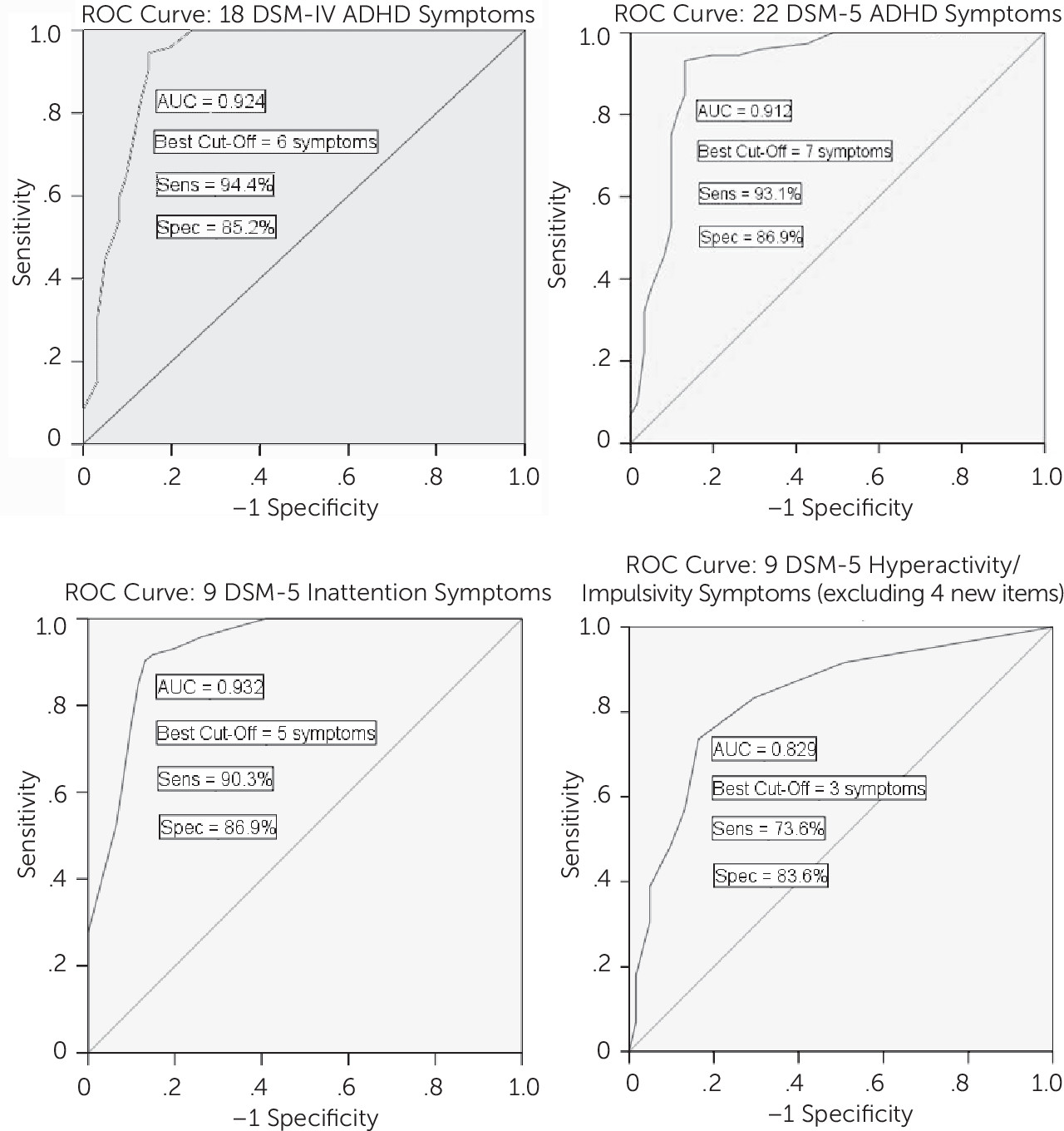

Finally, receiver-operating characteristic curves were built for testing the best cutoff (best balance between sensitivity and specificity) for the number of DSM-5 ADHD symptoms to predict clinical impairment (considering the above-described impairment cutoff). The following strategy was used: 1) initial comparison between DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria in terms of general performance in predicting impairment (area under the curve) and 2) determination of the best cutoffs for predicting impairment separately considering DSM-5 inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms. These models all assumed equal weighting of false positive and false negative errors in selecting the optimal cutpoint.

For all analyses, a 5% significance level for a two-tailed test was adopted (p<0.05). The analyses were performed in SAS (version 9.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC), Signal Detection Software ROC4, Mplus (version 6.11; Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA), and SPSS (version 20; SPSS, an IBM Company, Chicago, IL) software for APS analysis, receiver-operating characteristic curves, factor analysis, and other analyses, respectively.

Results

Clinical Representativeness of the Sample

The 68 ADHD cases in this study did not differ clinically or statistically from the general 440 ADHD outpatient clinic cases in terms of gender distribution, age, or marital, economic, or academic status. There were no significant differences between these groups in terms of ADHD clinical presentation (both type distribution and ADHD severity) and comorbidity profile (data not shown, but available on request).

Test–Retest Reliability of DSM-5 Proposed Criteria

Table 1 displays the results for test–retest reliability of DSM-5 criteria. The test–retest reliability was perfect (100% agreement) for the diagnosis of ADHD. Reliability varied widely for individual symptoms. Among inattention symptoms, all but three (fails to give close attention to details, reluctant to engage in mental tasks, and easily distracted) reached a moderate test–retest reliability with kappa coefficients >0.45 (p<0.05). In general, hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms tended to have more substantial test–retest reliability than inattentive symptoms. However, three of the four new impulsivity symptoms failed to reach significant test–retest reliability; as a group, their kappa coefficient was smaller (0.12–0.44) than the kappa coefficient of the hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms that were already present in DSM-IV (0.51–0.77).

Factor Structure of DSM-5 Proposed Criteria

Table 2 displays the factor structure of DSM-5 proposed criteria. For the list of 18 DSM-IV ADHD symptoms only, a three-factor solution provided a trend for a better fit for the data than a two-factor solution. For the list of 22 proposed DSM-5 ADHD symptoms, a three-factor solution provided a significantly better fit for the data than a two-factor solution. Nonetheless, both a two-factor solution and a three-factor solution yielded a satisfactory fit for the 18 DSM-IV ADHD symptoms as well as for the 22 DSM-5 ADHD symptoms.

Agreement Between DSM-IV and DSM-5 ADHD Diagnoses

Overall, the agreement between DSM-IV and DSM-5 ADHD diagnoses was high (kappa=0.82, p<0.001). The number of ADHD cases rose from 68 with DSM-IV criteria (51.1% of the total sample) to 80 with DSM-5 criteria (60.2% of the total sample), because 12 subjects that were not cases according to DSM-IV were defined as cases with DSM-5 criteria application.

Change in Clinical and Demographic Profiles With DSM-5 Proposed Criteria

Table 3 presents the clinical and demographic profile of the 68 ADHD cases according to DSM-IV and the 12 additional cases using DSM-5 criteria. Both groups had generally a similar demographic profile. However, additional DSM-5–derived cases had lower ADHD severity and disability scores. As expected, the 12 additional DSM-5 ADHD cases had a higher proportion of hyperactive/impulsive presentation and a lower (although not statistically significant) proportion of inattentive presentation (25% for inattentive plus restrictive inattentive versus 50%, p=0.10). The comorbidity pattern was generally similar between the two groups, except for conduct disorder, which was absent in the additional DSM-5 cases.

After documenting lower symptom severity and clinical impairment scores for DSM-5 additional ADHD cases, we performed secondary analyses addressing whether these cases are more severe and impaired than the controls. Mean SNAP scores were 1.51 (SD=0.53), 0.99 (SD=0.47), and 0.28 (SD=0.24) for DSM-IV ADHD cases (N=68), DSM-5 additional ADHD cases (N=12), and control subjects (N=53), respectively. For the same groups, mean Sheehan Disability scores were 5.85 (SD=2.04), 2.58 (SD=1.99), and 0.86 (SD=1), respectively. In analyses of variance, there were significant differences among the groups in both ADHD severity (F=119.5, df=130, 2, p<0.001) and clinical impairment (F=130.3, df=130, 2, p=0.001). In post hoc analyses with Bonferroni tests, means for all three groups remained significantly different from each other for both severity and impairment.

DSM-5 Proposed Symptom Performance in Predicting Clinical Impairment

Table 1 displays results of the performance of the 22 DSM-5 symptoms in predicting clinical impairment. Among the best 10 symptoms in bivariate tests (according to unadjusted odds ratio ranking), there were eight inattention symptoms (all inattention symptoms, except loses objects), one hyperactivity symptom (runs about), and one of the new impulsivity symptoms (uncomfortable doing things slowly).

In the conventional logistic regression analysis, a final model with three symptoms had the highest goodness of fit. This solution had a generalized R2 of 0.694 and a chi-square of 82.177. Three inattention symptoms (easily distracted, reluctant to engage in mental tasks, and difficulty organizing tasks) remained as independent predictors of clinical impairment.

In the APS regression, among the 10 top-ranked subsets of three symptoms, the three most recurrent predictors of impairment were also inattention symptoms (easily distracted, reluctant to engage in mental tasks, and does not follow through).

DSM-5 Proposed Symptom Performance in Predicting DSM-IV ADHD Diagnosis and Comorbidities

Table 1 displays results for the DSM-5 symptom performance in predicting DSM-IV ADHD. Among the best 10 symptoms in bivariate tests (according to unadjusted odds ratio ranking), there were seven inattention symptoms (all inattention symptoms, except loses objects and difficulty organizing tasks), one hyperactivity symptom (runs about), one of the impulsivity symptoms already present in DSM-IV (interrupts or intrudes), and one of the new impulsivity symptoms (uncomfortable doing things slowly).

In the conventional logistic regression analysis, a final model with five symptoms had the highest goodness of fit. This solution had a generalized R2 of 0.872. Three inattention symptoms (loses objects, easily distracted, and does not follow through), one hyperactivity symptom (runs about), and one new impulsivity symptom (difficulty to resist temptations) remained as independent predictors of DSM-IV ADHD.

In the APS regression, among the 10 top-ranked subsets of five symptoms, the five most recurrent predictors of DSM-IV ADHD were three inattention symptoms (does not follow through, easily distracted, and loses objects), one hyperactivity symptom (runs about), and one new impulsivity symptom (difficulty to resist temptations).

DSM-5 symptoms were also tested in their association with other psychiatric disorders (

Table 1). The odds ratios for these associations were much smaller than for the association with ADHD, and <30% of the associations between individual DSM-5 symptoms and comorbidity were statistically significant (even without any adjustment for multiple tests). The new impulsivity symptoms performed similarly to the other DSM-5 symptoms in this issue.

Best Cutoff of ADHD Symptoms to Predict Impairment

Figure 1 displays these results. The general performance in predicting clinical impairment was very similar using all 22 DSM-5 symptoms or only 18 DSM-5 symptoms (excluding the four new symptoms). Adding four new impulsivity symptoms did not improve the overall accuracy for identifying impaired individuals. Therefore, we performed additional receiver-operating characteristic curves including only the 18 DSM-5 symptoms that were already present in DSM-IV (but were reworded with new examples in the proposed DSM-5 criteria).

Considering the inattentive dimension, the best cutoff point for identifying impairment was five symptoms. For the hyperactivity/impulsivity dimension (again, using only nine symptoms total and omitting the four proposed new impulsivity symptoms), the best cutoff point was three symptoms.

Discussion

This seems to be the first comprehensive assessment of the two main modifications proposed by the DSM-5 Working Group affecting ADHD criteria in adults. Ghanizadeh

25 recently documented an 11% increase in children and adolescents with ADHD with DSM-5 criteria, a 0.75 kappa coefficient agreement between DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnoses, and a low specificity of the four new impulsivity symptoms for the diagnosis of ADHD.

In our study, most DSM-5 proposed symptoms had test–retest reliability with kappa coefficients in the moderate range (the majority of them in the range of 0.4–0.7). Recently, a kappa coefficient between 0.4 and 0.6 was considered a realistic goal and between 0.2 and 0.4 was considered still acceptable for DSM-5 diagnoses, based on similar test–retest reliability reported in the medical literature.

26 As a group, the four new impulsivity items had worse test–retest reliability compared with other hyperactivity/impulsivity items, and the “impatient” symptom presented very low reliability.

Our findings regarding the factor structure of DSM symptoms confirm those from previous studies in adult samples.

27 A three-factor solution provided a slightly better fit to the data than the two-factor solution for the DSM-IV original set of 18 symptoms and a more pronounced better fit for the DSM-5 set of 22 symptoms. However, the standard two-factor solution fits sufficiently well in both cases. Thus, there is little practical advantage for a three-factor model.

Using the 2010 APA proposal for DSM-5 criteria for ADHD, we identified 12 additional subjects as ADHD cases, which was a natural consequence of a lower threshold of symptoms (decrease from six to four for both dimensions) and a higher number of potential impulsive symptoms (e.g., positive diagnoses more easily achievable in the hyperactive/impulsive dimension with the threshold of four of 13 than with six of nine proposed in DSM-IV). The proportion of women was higher among these 12 additional ADHD cases. Applying both proposed changes in ADHD criteria for adults at the same time captured new cases that had less severe ADHD and were less clinically impaired. Overall, these findings suggest that using the proposed changes together might change the ADHD case profile. However, these new ADHD cases are significantly more symptomatic and impaired than control subjects. Our findings concur with previous studies suggesting that DSM-IV criteria with a six-symptom cutoff may capture only the most extreme portion of adult ADHD cases.

8,11The proposal of including four new impulsivity symptoms may have negative consequences for both clinical and research settings (e.g., difficulty in interpreting data from former classificatory systems, need to change symptomatic scales, prevalence changes, or deriving ADHD cases with a different response pattern to treatment strategies). Therefore, it is important to test whether these symptoms might have stronger associations with ADHD diagnosis and/or impairment compared with traditional ADHD symptoms. In our study, the three-step analysis revealed that inattentive symptoms were in general better predictors of clinical impairment and ADHD diagnosis than hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms. No consistent pattern of association was detected with either ADHD diagnosis or with clinical impairment for the four new impulsivity symptoms as a group.

It is also important to note that none of the 22 DSM-5 symptoms had a weaker association with ADHD diagnosis than with comorbidities, concurring with findings from Kessler et al.,

12 who reported that their set of best symptoms was more related to ADHD than to comorbidity. That study addressed the best predictors of ADHD diagnosis among DSM-IV ADHD symptoms plus 14 non-DSM symptoms (mostly related to executive functions). All inattention symptoms had a stronger association with ADHD diagnosis than hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms (odds ratio, 24.1–694.6 versus 1.8–16.8). In an APS regression including all items, three non-DSM symptoms (difficulty prioritizing work, trouble planning ahead, and cannot work unless under a deadline) and one DSM inattention item (difficulty sustaining attention) were the best predictors of narrowly defined ADHD (meeting full childhood and adulthood criteria). None of the hyperactivity or impulsivity symptoms were among the best predictors of ADHD.

Barkley et al.

11 reported similar findings. Among DSM-IV ADHD symptoms, one single inattention symptom (easily distracted) was sufficient for discriminating adults with ADHD from community controls in a study conducted at the University of Massachusetts. A set of three inattentive symptoms (fails to give close attention to details, difficulty sustaining attention, and does not follow through) and one hyperactivity item (excessively loud) was sufficient for discriminating ADHD cases from clinical controls. In the same study, the five ADHD symptoms with strongest associations with the presence of any impairment were inattentive symptoms. A population-based study also recently documented that inattentive symptoms were the most strongly associated with clinical impairment.

5 Overall, the specific list of best predictors of ADHD diagnosis or clinical impairment has some variation across the studies, but these results and our findings are consistent in reporting that inattention symptoms are usually better predictors than hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms.

Clinicians will be asked to decide whether ADHD is present based on the number of symptoms in both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. In DSM-IV, this cutoff point in both instances is six of nine symptoms. It has not been clear whether this cutoff is adequate in adults. In our study, a lower threshold than the one in DSM-IV was the best cutoff for capturing clinical impairment (five of nine inattentive symptoms and three of nine hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms and not using the four new impulsivity items). These findings concur with previous studies suggesting that a lower threshold of symptoms would work better in adult ADHD samples.

7,9 Another study addressed this issue in a large population-based sample (aged 18–75 years) in The Netherlands, reporting that subjects with ≥4 DSM-IV symptoms in any ADHD dimension were significantly more impaired than subjects with fewer symptoms.

8This study has some limitations. Our findings should be extrapolated with caution for nonclinical populations and other clinical samples with different cultural backgrounds. It is not possible to exclude that some of the analyses might have been underpowered, because the sample size was moderate. Particularly, our test–retest sample was small and only included cases. The same clinician applied DSM-IV and DSM-5 ADHD criteria and an impairment scale. Although this nonblind assessment might have determined a higher agreement between DSM-5 and DSM-IV results, there is no reason to expect a substantial bias in assessing individual symptom performance and determining the best cutoff point. Finally, the cutoff point determined for both dimensions was obtained allowing free variation of symptoms in the other dimension. Although we could have run conditional analyses for searching different cutoff points for ADHD-I and ADHD-H than those detected for ADHD-C, this was neither the approach used in previous studies nor the one used in current diagnostic classifications. Nonetheless, there is a scarcity of field trials of DSM-5 criteria for ADHD in adults, and this study adds important information on the reliability and validity of the 2010 DSM-5 ADHD proposed criteria.

Conclusions

Overall, our findings suggest that the proposed four new impulsivity symptoms do not improve ADHD diagnosis sufficiently to surpass potential negative effects of changing diagnostic criteria, such as modifying ADHD prevalence and correlates, needing to reconstruct ADHD scales, and losing comparability with research from the last 20 years.

On the other hand, our study reinforces that a lower cutoff point for the number of inattentive and/or hyperactive/impulsive symptoms might be more adequate for adult patients. However, this result must be balanced against the risk of potential increase in ADHD prevalence using a lower threshold of symptoms. This issue might have even more significance in the general population. The population consequences of using a lower cutoff point for ADHD diagnosis on prevalence rates and cases profile are largely unknown. Therefore, future studies testing the effect of this criterion change in large population samples are needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Helena Kraemer for statistical advice, Paulo Abreu for support in data collection planning and coordination of the adult ADHD outpatient program, and Giovanni Salum Jr for support in APS analyses.