Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) was originally conceptualized as a static and possibly progressive neurological disorder affecting some boxers who had a tremendous exposure to neurotrauma.

1,2 In 1928, Martland

1 described a “peculiar condition” affecting long-career boxers that appeared to be clearly neurological, in that it included gait disturbance, dysarthria, tremor, and cognitive impairment. Martland referred to this syndrome as “punch drunk,” and other authors termed it “traumatic encephalopathy,”

3 “dementia pugilistica,”

4 and “CTE.”

5 For the next 40 years, the syndrome was only described in case studies. The first and only large study of CTE in 80 years (1929–2009) was conducted by Roberts

2 and was published as a book in 1969. Roberts

2 reviewed the case studies that had been published between 1929 and the late 1960s and reported that the boxers had fairly obvious neurological deficits. However, there was limited understanding of the clinical features and there was no information on the prevalence of the syndrome. Roberts began with a list of 16,781 retired boxers and obtained an age-stratified random sample of 250. Of those, 16 had died, nine emigrated, and one refused to participate in the study. Of the 16 who died, there were no confirmed cases of suicide, although there was one suspicious death associated with carbon monoxide poisoning. After clinically examining the 224 retired boxers, Roberts concluded that 11% had a mild form of the syndrome and 6% had severe problems. This remains the largest clinical study of possible CTE published to date.

Through the process of examining these 224 retired professional boxers, Roberts

2 made some important observations. First, he established a statistical association between exposure and the clinical syndrome. For example, for boxers aged >50 years who had ≥150 fights, 50% had the syndrome compared with 7% who had <50 fights. Second, many of the boxers had neurological problems (e.g., speech or gait problems) toward the end of their careers while they were still active fighters. Third, he noted that many people with the syndrome had a static course, but a small number of others appeared to have a progressive course greater than expected from natural aging. Fourth, Roberts

2 noted that some boxers had other health problems and neurological conditions that either co-occurred with the syndrome or were more likely to be the predominant underlying cause of the clinical symptoms (e.g., cerebrovascular disease). Finally, he discussed personality changes, social decline, and psychiatric problems in some former boxers, but he struggled to determine the extent to which they were caused primarily by the neurological syndrome. He did not consider depression or suicidality to be a clinical feature.

Approximately 40 years later, CTE was conceptualized in much broader terms. The clinical features described as characteristic of CTE are now broad and diverse, including headaches, anxiety, depression, suicidality, anger control problems, gambling problems, gait problems, dysarthric speech, mild cognitive impairment, motor neuron disease, and dementia.

6–13 In fact, it was found that a person with no clinical symptoms could have CTE.

7 The problem from a clinical perspective is that the neuropathology, even in small amounts, has been considered sufficient to diagnose the syndrome, even if there were few or no symptoms present. By comparison, this is tantamount to concluding that people with a small amount of neuropathology associated with Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease have the disease, even if they appear clinically normal at that point in life. The situation has been further complicated by the implicit, and often explicit, assumption that any clinical feature present before death must be mostly caused by the neuropathology believed to be unique to CTE.

6–13 As such, CTE, over the past few years, appears to have been woven into a Gordian knot.

In the published literature, between 1928 and 2009, suicide was not considered a clinical feature of CTE. In a 2009 review, McKee et al.

6 identified 48 cases of CTE in the entire literature, carefully documented their clinical and neuropathological characteristics, and added three additional case studies. McKee et al.

6 did not report suicide to be a clinical feature of CTE. In 2010, Omalu et al.

14 published their third case of CTE in a former National Football League (NFL) player. With this work, Omalu et al.

14 introduced the finding that suicidality was a prominent clinical feature of CTE. This conclusion appears to be based on the fact that suicide was the cause of death of two of the three cases examined by Omalu et al.

14; however, the extent to which it was influenced by the extraordinary media coverage of all of the case studies during that period is unknown. In recent years, it has been asserted that suicide is a common clinical feature of CTE,

7–13 although three review articles concluded that current scientific evidence does not support these assertions.

15–17 Nonetheless, it is now common for clinicians and researchers to adopt the assumption that suicide is an established clinical feature of CTE.

In an epidemiological study reporting causes of death in former NFL players, nine completed suicide over the course of 47 years (1960–2007), a rate that is less than one-half of what is expected from men in the general population.

18 Therefore, before 2007, the best available evidence indicated that former NFL players were at substantially lower risk for suicide than men in the general population. In stark contrast, the media reported that at least six current or former NFL players completed suicide in 2012 alone, all by self-inflicted gunshot wounds, suggesting a recent increase in the incidence of suicide in current and former NFL players. It is important to carefully consider and review the possible associations between repetitive neurotrauma, neuropathology, CTE, and suicide.

Risk Factors for Depression and Suicide in Men

There has been an assumption in the literature (and the media) that the neuropathology of CTE causes depression and increases the risk for suicide in former athletes and military veterans. However, risk factors for suicide in former NFL players and other collision sport athletes should be considered in the broader context of the risk for suicide in the general population. There is a vast amount of global literature on suicidal ideation, plans, attempts, and completed suicide in adolescents, adults, and older adults. Risk factors for suicidality (e.g., ideation and behavior) and completed suicide are diverse, extend far beyond depression, and include the following: 1) childhood adversities such as physical abuse, sexual abuse, or family violence

24; 2) interpersonal or family conflict

25; 3) financial difficulties

26; 4) substance abuse

27,28; 5) physical illnesses

29 and poor general health

30; 6) chronic pain

31–33; 7) personality disorders

34; 8) impulsivity and aggression

35–37; 9) limited social connectedness

38; and 10) hopelessness.

39 Certain high-risk cognitive states are associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior (see Brown and Green

40 for a review). Examples include hopelessness

41,42 and problem-solving deficits such as difficulty conceptualizing adaptive solutions to life problems.

43 Perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (a belief that one does not have meaningful interpersonal relationships) might also be related to suicidal ideation and behavior in some people.

44 Major interpersonal stressful life events might precipitate suicide attempts in adults with alcohol problems.

45Depression is a prominent risk factor for suicidal ideation and behavior. Depression is fairly common in men across their lifespan, and suicidality is a cardinal diagnostic feature of major depressive disorder.

46 The 12-month prevalence of depression in men born in the United States is 13.9%, 12.4%, 10.1%, 7.8%, and 4.3% for those aged 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, and 65–74 years, respectively. The lifetime prevalence of depression in men in these five age cohorts is 26.1%, 28.1%, 27.3%, 21.9%, and 15.9%, respectively.

47 In general, depression is believed to arise from the cumulative effects

48–50 of genetics,

51–54 adverse events in childhood,

55–58 and ongoing life stressors.

59–62 Moreover, people with a variety of health problems and medical conditions (e.g., diabetes,

63–65 cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease,

66–70 chronic headaches,

71–74 hypothyroidism,

75 chronic insomnia,

76 low testosterone,

77–79 obesity,

80 stroke or small-vessel ischemic disease,

81,82 Parkinson’s disease,

83 and Alzheimer’s disease

84) are at increased risk of having depression.

Chronic pain is bidirectionally associated with depression

85–89; individuals with depression are more likely to have chronic pain and those with chronic pain are more likely to experience depression—and each condition might serve as a magnifier for the other. Hooley et al.

33 proposed a theoretical model for how people with chronic pain are at increased risks for suicidal ideation and behavior. This model included a pathway involving a combination of depression, psychache (unbearable psychological pain), desire to escape physical pain, increased capability for suicide, sense of burdensomeness, and thwarted sense of belongingness.

The rate of chronic pain and opioid use in former NFL players is relatively high,

90 and those retired players with depression and chronic pain also have greater life stress and financial difficulties.

91 Researchers have reported that people seeking treatment for chronic pain have high rates of comorbid depression,

92 and individuals with chronic pain are at increased risks for suicidal ideation

93 and suicide.

31 As such, retired football players with life stress, financial difficulty, chronic pain, and depression are likely at increased risk for suicidal ideation—and they might be at increased risks for suicide attempts and completed suicide. In a recent media-based anonymous survey of 763 retired NFL players, a large number reported having difficulty adjusting to life after football (61%), having difficulty finding employment (34%), struggling financially (51%), experiencing marital problems (48%), taking prescription painkillers (27%), and experiencing some degree of depression (31%).

94Importantly, it is well established that people who sustain traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) of all severities are at an increased risk of having depression.

95–100 TBI is also a relative risk factor for suicidality

101 and suicide,

102,103 although the absolute risk is small. In a longitudinal epidemiological study of 218,300 individuals, TBI was independently related to an increased risk for completed suicide, those with moderate or severe TBIs were at greater risk (compared with those with mild TBIs), and individuals with depression or substance abuse problems were at the greatest risk.

104 The rate of suicide in the epidemiological study was as follows: general population (0.03%), TBI and no psychiatric disorder (0.1%), TBI and a psychiatric disorder (1%), TBI and depression (1.5%), and TBI and substance abuse (1.6%).

Depression is also common among those with dementia; 25%−50% of these individuals experience depression at some point over the course of their illness.

105,106 There are now numerous studies reporting a relationship between depression, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. Depression is the most frequently reported psychiatric disorder among individuals with mild cognitive impairment,

107 with one in five people with mild cognitive impairment reporting moderate to high levels of depression.

108 In one study, symptoms of depression were reported in 51% of patients with mild cognitive impairment seen in a rural memory clinic.

109 There is some evidence that depression is associated with an increased risk for progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease,

110–113 although not all studies have shown this relationship.

114 Depressive symptoms in individuals suffering from mild cognitive impairment have also been associated with greater atrophy in brain regions associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

115In conclusion, survey research suggests that former NFL players might be at increased risk for depression.

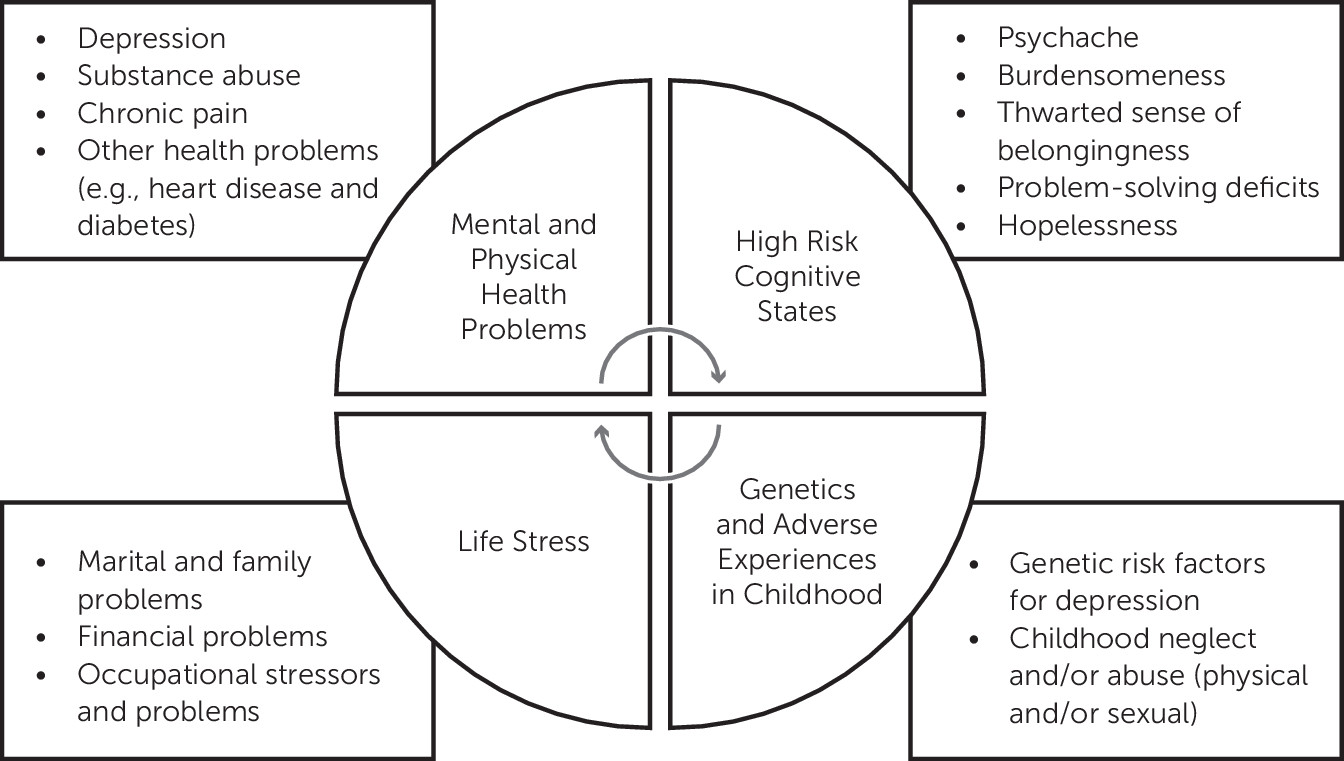

48,92 NFL players are not immune, of course, to depression manifesting for similar biopsychosocial reasons as it does in other men, or to the many other risk factors for suicide that are present in the general population. Therefore, depression and suicidality in former athletes, including NFL players, might be multifactorial in causation and may or may not relate to specific types of neuropathology such as region-specific depositions of abnormal hyperphosphorylated tau. Factors related to depression and suicidality in the general population are listed in

Table 1. Future research is needed to determine whether regionally specific depositions of tau can be added to this list.

Causation and Comorbidity

The autopsy case studies and case series that have been published in the past few years describe a diverse range of clinical symptoms (including mental health problems), state that those clinical symptoms are “characteristic” of CTE, and state or imply that the predominant underlying cause of these clinical features is delayed-onset, progressive, degenerative neuropathology. It will be a major challenge to test this causal theory because there has been a conflation of a broad range of neuropathology with a broad range of clinical symptoms reported by family members before a person’s death (i.e., they co-occur; therefore, they must be unidirectionally causally related), and the conflation is potentially magnified and reinforced by known comorbidities that are present in the general population. Simply put, some of the symptoms and problems that have been attributed to the neuropathology of CTE in the case studies presented in the literature in the past few years are known to co-occur in men in the general population who do not have exposure to repetitive neurotrauma and who do not have CTE. This is especially true for depression, anxiety, chronic pain, chronic headaches, substance abuse, impulsivity, irritability and aggression, and mild cognitive impairment.

Depression is a good example of a condition that has behavioral comorbidities that resemble modern CTE. Authors of several lay and academic books suggest that men who are depressed are often irritable, angry, and aggressive—and they engage in risky behaviors involving sex, alcohol, drugs, and gambling.

116,117 Researchers have also reported that anger

118 and irritability

119,120 are associated with depression. Compared with women, men with depression have greater irritability, have lower impulse control, are more likely to overreact to minor annoyances and have anger attacks, and are more likely to abuse alcohol and drugs.

121,122 Therefore, many of the clinical features attributed to CTE are actually comorbid in men with depression who do not have a history of repetitive neurotrauma.

There are five basic models for conceptualizing comorbidity. First, the comorbidity might be spurious in that it arose by coincidence or ascertainment bias. Without question, the former athletes and NFL players who have been examined at autopsy for CTE are highly selected and nonrepresentative and a disproportionate number have suicide as their cause of death. Thus, the ascertainment bias issue as a contributor to the assumed clinical-neuropathological associations in CTE is present and very important to consider and study. A second model of comorbidity is that the comorbidity might be unidirectional in that one condition causes another. Third, there might be a bidirectional causal relationship between the two conditions. Examples of relevant bidirectional causal relationships reported in the literature include depression and chronic pain,

85–89 migraine and depression,

73,123 depression and marital problems,

124–126 and depression and alcohol dependence.

127 Fourth, the two conditions might be comorbid due to shared underlying risk factors (genetic, environmental, or both). Depression and anxiety are bidirectionally related, but they are also comorbid because they share both environmental (e.g., childhood adversity and current life stressors) and genetic risk factors. Finally, genetic and/or environmental risk factors might produce a state of neurobiology that underlies both of the related conditions. To advance knowledge in CTE, we must carefully consider and try to better understand comorbidities.

Conclusions

The clinical syndrome of CTE, as described in recent years in retired athletes, departs substantially from descriptions of the syndrome from 1929 to 2005, by having a particular emphasis on depression and suicide. It is essential to appreciate that the causes of suicidal ideation, attempts, and completed suicide are complex, multifactorial, and difficult to predict in individual cases. In the general population, there are many biopsychosocial risk factors for depression and/or suicidality, such as genetics, adverse events in childhood, personality disorders, life and financial stressors, marital and family problems, limited social connectedness, hopelessness, substance abuse, impulsivity, aggression, chronic pain, chronic insomnia, chronic headaches, diabetes, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, hypothyroidism, low testosterone, TBI, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. The extent to which one or more of those factors is related to depression and/or suicidality in individuals can be difficult to determine—and it is usually assumed that the underlying cause of both depression and suicidality is multifactorial in most people. A simplified model for risk for suicide in men is presented in

Figure 1.

Maroon et al.

17 reported that there were no cases of suicide in association with CTE before 2002. The rate of suicide in former NFL players, based on an epidemiological study tracking causes of death between 1960 and 2007, was less than one-half of what was expected from men in the general population.

18 In the first review of all known cases of CTE,

6 suicide was not considered a feature of the disease. Therefore, until recently, former NFL players appeared to be at substantially lower risk for suicide than men in the general population.

In the recent literature, it has been asserted and assumed that suicidality and completed suicide are common clinical features of CTE. The extent to which this belief has been reinforced in the general public and the medical and scientific community by thousands of media stories is unknown. However, the science underlying the assertions and assumptions that suicide is caused in whole or part by the neuropathology of CTE, or that it is a core clinical feature of CTE, is extremely limited, inconclusive, and, in fact, contradictory. Therefore, it is currently premature to assume that people with the neuropathology believed to be characteristic and unique to CTE are at an increased risk for suicide. This remains extremely difficult to study because as of 2015, there are no agreed-upon and validated clinical (or neuropathological) diagnostic criteria for CTE. As such, the disease cannot be reliably or accurately diagnosed in a living person.

Future studies relating to suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicide in former athletes—those with and without a history of repetitive neurotrauma—are needed to determine whether neuropathology specific to repetitive neurotrauma can be added to the list of known risk factors for completed suicide. In addition, given the thousands of media stories relating to contact sports and CTE, it might be important to examine whether media coverage has had an adverse psychological effect on retired athletes, and whether repeated exposure to news stories elicits or reinforces suicidal ideation in some at-risk athletes. There are many studies relating to “contagion”

128 and the influence of the media on suicidal behavior.

129–132 As such, there are several mechanisms by which the media coverage reporting a causal relationship between contact sports, CTE, and suicide could be contributing to psychological distress in former athletes. Finally, although it is difficult to study directly, it might be possible to indirectly study whether the diagnosis or misdiagnosis of CTE by a health care provider could have iatrogenic effects in regard to suicidal ideation. For older adults, concerns have been expressed in the literature relating to early (e.g., preclinical) diagnosis of dementia and whether that might cause or contribute to depression or suicidality in some people,

133,134 although some researchers have reported that the risk for depression or suicidality after receiving a diagnosis in those with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease is small.

135 Living with an incurable neurological disease, such as multiple sclerosis, can be extraordinarily stressful and presents tremendous uncertainties in a person’s life,

136,137 and some people with progressive neurodegenerative diseases, such as Huntington’s disease, perceive suicide as a viable option for them given the realities of their future.

138 Moreover, in a survey of adults in the general population and U.S. veterans, 60% and 69%, respectively, said that a person has a right to commit suicide if he or she has an incurable disease.

139In conclusion, surveys have revealed that a substantial minority of former NFL players have mental health problems.

47,91,140 Future research is needed to determine the extent to which abnormal tau deposition in the brains of former athletes is 1) progressive, 2) the driver of diverse clinical symptoms, and 3) a unique contributor to suicidal ideation and behavior. However, conceptualizing suicide as being the result of small focal epicenters of tau, or a progressive degenerative tauopathy, is currently scientifically premature, overly simplistic, and potentially fatalistic. It is important for health care providers to appreciate that there are multiple underlying biopsychosocial causes for mental health problems in former athletes—and these mental health problems might improve substantially with treatment. This reinforces the pressing need to provide evidence-based mental health treatment to those who are experiencing depression, substance abuse problems, and life stressors.