There is little research regarding the neuropsychiatric aspects in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in Hispanics. During MCI progression, cognition declines greater than expected for an individual’s age and education level, but without interference in activities of daily living.

1 Uncertainty persists regarding the diagnostic criteria for MCI, as well as the boundaries between normal aging and MCI and between MCI and mild Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

2 The diagnosis of MCI has traditionally been based on clinical cognitive symptoms and supported by test results.

3 There is increasing awareness of the importance of the neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) associated with MCI diagnosis, as such symptoms predict a high likelihood of progression to AD.

4 The neuropsychiatric pattern of MCI has been previously described among a predominant non-Hispanic white community sample, differentiating MCI from both mild Alzheimer's disease cases, and normal controls (NC).

5 This most likely implies that a clinical, and possibly a biological, continuum exists, which merits further exploration and may help identify populations at risk for developing AD.

Data from the Texas Alzheimer's Research and Care Consortium (TARCC) may help confirm the hypothesis that MCI is an intermediate state between normal cognitive functioning and AD. TARCC is a well-characterized Alzheimer's disease cohort in which all subjects receive annual comprehensive psychometric assessments, clinical and neurological examinations, expert consensus diagnosis, and blood-based genetic and protein bio-markers, including a Genome Wide Association Study (GWAS) panel.

Mexican American recruitment in TARCC has been of particular importance and relevance and our cohort of study is predominantly represented by this membership. Among the currently estimated 200,000 Hispanics with AD in the United States, a significant number remain undiagnosed and untreated, and Hispanic participation in AD clinical trials has been historically low.

6 Currently, Hispanics represent 16% of the U.S. population.

7 Studies show a higher prevalence and incidence of AD among Hispanics compared with non-Hispanic whites.

8 On the other hand, the presentation of AD-related NPS at the time of diagnosis may be somewhat different among Hispanics than the white majority population.

9 For example, Chen et al.

10 examined stage-specific prevalence of NPS and its relationship to severity of AD in a multiethnic community sample and found a relationship between a higher level of education and a lower frequency of anxiety and sleep disturbances. More so, Ortiz et al.

11, in a systematic cross-ethnic comparison of NPS between a community sample of Hispanics with AD, an age-matched Hispanic control group, and an AD group of non-Hispanic white patients, found that on the 12-item Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), apathy and anxiety were the most often reported symptoms in the Hispanic AD group, whereas apathy and depression were the most commonly reported symptoms in the non-Hispanic AD groups. Additionally, it appears that AD symptom onset occurs at an earlier age in Hispanics than in non-Hispanic whites.

12 However, the literature on this topic is conflicting.

13,14 In a more recent cross-sectional study of community-dwelling participants 50 years and older, who were Hispanic and white non-Hispanic residents of Southern California, Hispanics were younger by an average of 4 years at the time of diagnosis, regardless of dementia subtype (probable AD, or probable vascular dementia). The earlier age at diagnosis for Hispanics was not explained by gender, dementia severity, years of education, history of hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, or diabetes. Only ethnicity was significantly associated with age of onset.

15Results

Table 1 shows the variables of interest, post hoc tests, and main effect. In the unadjusted analysis, individual NPI-Q symptom items scores and total NPI-Q severity scores differed significantly across the three groups. Adjusted associations of NPS with groups are shown in

Table 2. MMSE and IADL were found to be consistently associated with MCI compared with control, AD compared with control, and AD compared with MCI as well. Education and NPI-QTOT were associated with AD but not with MCI compared with controls. Increase in the CDR-SOB was associated with increased odds of AD compared with MCI. NPI-QSUB and gender were associated with MCI but not with AD compared with controls.

Table 3 presents unadjusted association of considered factors with NPI symptoms by ethnicity and separately for each group. Both individual NPI-Q symptoms scores (p=0.0007) and total NPI-Q severity scores (p=0.002) differed significantly between Hispanic and non-Hispanic subjects among AD cases only but not among those with MCI. In controls, individual NPI-Q symptom scores were different between Hispanics and non-Hispanic subjects (p=0.0058). In addition, MMSE, GDS, and IADL were also found to be different between Hispanics and non-Hispanics. These differences in GDS symptoms, MMSE scores, along with CDR-SOB, persisted between Hispanics and non-Hispanics in the MCI group. In AD group, along with NPI symptoms, only GDS and MMSE were found to be different between Hispanics and non-Hispanics (

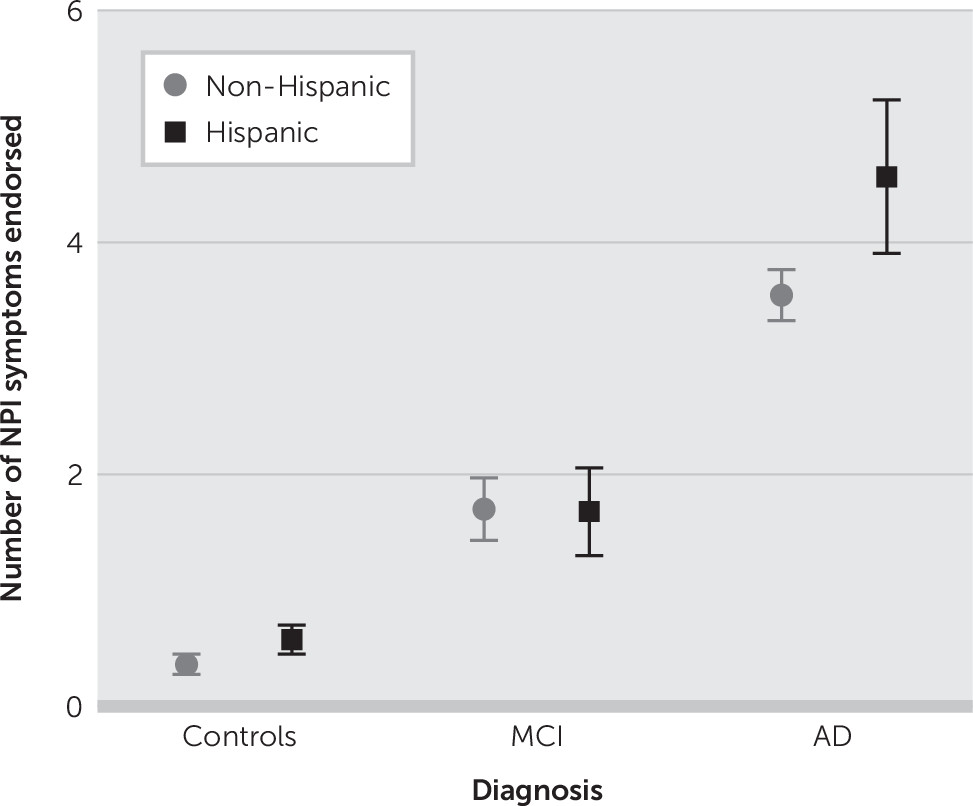

Table 3). Average number of endorsed NPI-Q behaviors by diagnosis and ethnicity are displayed in

Figure 1.

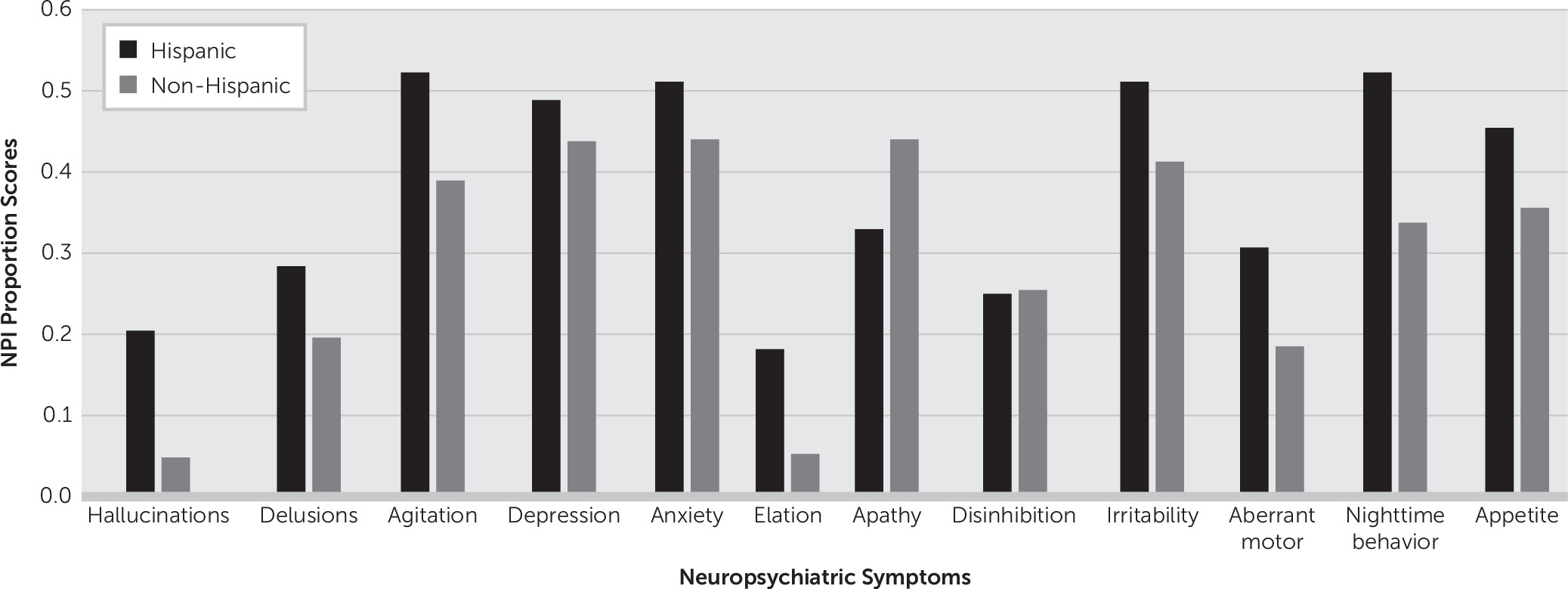

Figure 2 presents the proportion scores of individual NPS differences in the AD group stratified by ethnicity.

In multivariable analysis (

Table 4), Hispanic ethnicity was associated with both total NPI symptom severity scores and individual NPI-Q symptom items scores in the AD group after adjusting for age, CDR-SOB, GDS, IADL, MMSE, and gender but not with the MCI group. NPI individual symptoms (NPI-QSUB) also showed an association with Hispanic ethnicity in the control group that fell short of statistical significance. In MCI group, only CDR-SOB and GDS were significantly associated with NPI symptoms.

Key Findings

First, we found an ordinal increase in the average number of endorsed NPI behaviors by diagnostic group. These differences on NPI remained after controlling for age, education, MMSE, CDR-SB, GDS, and IADL. These findings further support the initial hypothesis by Lyketsos et al. that if indeed MCI is a precursor to AD, then the frequency of neuropsychiatric symptoms should intermediate between normal and that of dementia.

30 Also, earlier literature on this research question further supports our findings.

5 Second and most interestingly, differences in NPS severity by ethnicity in subjects with AD, but not MCI, were observed (

Figure 1). Additionally, being of Hispanic ethnicity was a significant factor associated with NPS in the control group and AD group, but interestingly not in the MCI group; more so, in the control group, individual NPI-Q symptom item scores (NPI-QSUB), but not total NPI-Q severity scores (NPI-QTOT), showed an association with Hispanic ethnicity that nearly reached statistical significance. Finally, GDS scores were strongly associated with NPS among the three groups.

In AD cases, psychotic symptoms like hallucinations, nighttime behavioral disturbances, and elation were predominant in Hispanics, while apathy was more common in non-Hispanic whites (

Figure 2). This difference indicates that the presentation of dementia, and therefore possibly its etiology, may differ between these two populations (Hispanic and non-Hispanic).

Discussion

This study presents findings from a descriptive and comparative analysis of NPS found in elderly Hispanic and non-Hispanic white NC, MCI, and AD subjects. Differences in NPS severity by ethnicity in subjects with AD but not MCI were found. All patients were evaluated using rigorous diagnostic criteria and were well matched in terms of age, gender, and dementia severity.

Although this study suggests that there are ethnic differences in AD’s psychopathology presentation, it has several limitations. We must rely on subject self-report for the ascertainment of ethnicity, albeit confirmed by informants. While TARCC is collecting genetic data, those are not yet available. It may one day be possible to confirm our findings by genetic admixture. Regardless, previous studies suggest a strong overlap between self-reported Mexican American ethnicity and genetic admixture.

31Within this limitation, we found significant cross-ethnic differences in the psychopathological symptom burden of AD, but not in MCI. Our study presents both new findings and results consistent with earlier studies. New findings include that despite high proportions of NPS in subjects with MCI in elderly Hispanic and non-Hispanic groups, differences in NPS severity by ethnicity was not statistically significant in the MCI group. We also confirmed the existence of MCI as a transitional stage between normal cognition and AD based on the distribution of the mean number of endorsed NPI behaviors by diagnosis and ethnicity. It is also noteworthy that after adjusted association of considered factors with NPS by groups, individual NPI-Q symptoms also showed an association with Hispanic ethnicity in the control group that fell short of statistical significance, suggesting early presence of NPS in Hispanics.

During the initial diagnostic evaluation, measures of acculturation, culturally validated and normed neuropsychological tests, and a validated inventory for the classification of NPS, the NPI-Q, were used. The study employed only bilingual and bicultural clinicians and raters for assessment of Hispanic subjects to enhance the validity and accuracy of the data collected. With this in mind, among the 12 NPS items of the NPI-Q, nighttime behavioral disturbance, agitation/aggression, depression, anxiety, and irritability (mood and motor cluster) were the most often reported symptoms in the Hispanic AD group, whereas apathy, agitation, depression, anxiety, and irritability were the most commonly reported symptoms in the non-Hispanic AD group. More so, hallucinations and elation were disproportionately higher symptoms among Hispanics.

Our hypothesis is further supported by a recent study

32 in Mexican Americans, in which one TARCC site was included in the analyses. The purpose of that study was to characterize Mexican Americans who met criteria for AD and MCI. O’Bryant et al. found significant differences in presentation between Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites, regarding age at onset of dementia (earlier), years of education (less educated), cognitive performance on MMSE (lower scores), and possession of the ApoE ε4 allele (predictor of a more rapid progression of MCI to AD), which was less frequently expressed in this study among Mexican Americans than in non-Hispanic whites, respectively. Mexican Americans endorsed more symptoms of depression as measured by the GDS-30.

These differences, including the neuropsychiatric profile of AD between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites, observed in our study have multiple implications for future research. NPSs are frequently associated with caregiver burden.

33 These symptoms persist and are resistant to treatment. In comparison to the non-Hispanic white population, the frequencies of NPS were higher in Hispanics with AD. Research is only beginning to sort out the complicated picture of dementia and particularly AD among Hispanics. Elderly Hispanics are vulnerable to dementia, but “dementia” is a complex syndrome with heterogeneous genetic and environmental factors. That association is further complicated by the ethnic/racial diversity of Hispanics in the United States.

The limited research to date suggests that within-group differences may affect the incidence and presentation of AD.

8,9,34 Evidence supporting this hypothesis comes from a recent population-based study (i.e.,

not selected for dementia) of 925 community-dwelling Mexican American participants of the Hispanic Established Population for the Epidemiological Study of the Elderly (HEPESE).

35 In this study, a high prevalence (62.7%) of NPS was found by using the NPI

36 as a measure of psychopathology among Mexican Americans. Most importantly, the authors also compared their study to other population-based studies in other countries (Brazil and Spain), and one in the U.S. Surprisingly, they showed a similar distribution of NPI symptoms across groups, with the exception of selected symptoms (irritability, apathy, and weight changes) that can be seen with higher rates in cases of advanced stages of dementia.

35Here, we report that NPS occurs frequently in MCI and Alzheimer’s dementia. Similar study findings have been reported in the literature by Ortiz et al.

11 They found that NPS is common in AD, regardless of ethnicity, but that Hispanic AD cases presented to the initial assessment with more NPS than non-Hispanic whites.

These findings could have significance for the understanding and treatment of dementia in the Hispanic population. Hispanic elders represent one of the fastest growing minority populations and are projected to account for 16% of the older U.S. population by the year 2050. Most older Hispanics are estimated to be of Mexican origin.

37 Additionally, neuropsychiatric disturbances are common manifestations of dementing disorders like AD. Such symptoms, particularly when there is a psychotic driver for abnormal behavior, are linked to higher rates of institutionalization and more rapid cognitive decline.

38Whether Hispanics are at exceptional risk for dementia and NPS cannot be determined from these data. Here, we do confirm a higher frequency of NPS in Hispanics with AD as seen in other studies including the one by Sink et al.

39 The high frequency of NPS in both MCI and AD groups as seen in our study has been reported in other studies to be associated with caregiver burden and to pose unique challenges for caregivers.

40Limitations of our study include its cross-sectional design and lack of well standardized norms for neuropsychological instruments in Hispanics that may transpire into the possibility of cognitive test bias. That is, if the neuropsychological tests utilized within the study were biased against Mexican Americans, this bias could have influenced the diagnostic process, which in turn could affect the makeup of the MCI groups by ethnic groupings. TARCC has been part of the generation of the Texas Mexican American Normative Studies (TMANS), which is designed to specifically provide normative data for Mexican American adults and elders.

In addition, specific psychosocial determinants need to be taken into consideration when interpreting the demographic distribution of the data presented among groups. Hinton et al. have reported how cultural and other psychosocial factors are important in shaping the clinical presentation of Hispanics and how the use of informants or caregivers in assessing NPS in demented Hispanics can be problematic,

16 for example, the unwillingness of Hispanic caregivers to seek professional help despite high levels of distress in their dementia caregiving situation. Although the ethnicity composition was balanced in the control (43.1% versus 56.9%) and MCI (39.82% versus 60.18%) groups, the ethnic composition in the AD group, specifically the number of nonwhite Hispanics, is extremely underrepresented, 99 versus 876 subjects, respectively (i.e., 10.16% versus 89.84%). Nevertheless, elevated NPI-Q scores were higher in the Hispanic group.

Possible explanations for this include among Hispanics: increased health care barriers, low utilization of healthcare services unless it is urgent, the stigma associated with a dementia diagnosis, and the Hispanic caregivers’ perceptions about values and beliefs about medicine and treatment. Finally, language proficiency and economic status remain common barriers among elderly Hispanic subgroups.

41Strengths of TARCC’s cohort include the large number of participants, including a relatively large sample of Hispanics, longitudinal assessments, and the potential for future biomarker associations. Being a retrospective secondary analysis of established data gives further credence to the results and test hypothesis.