Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system, resulting in neurological and psychological symptoms. Cognitive impairment is a common feature of the disease across all disease stages and is experienced by up to 65% of patients.

1 Psychological symptoms and cognitive impairment have both been shown to affect a patient’s overall quality of life and employment status.

2 There is a complex interplay between these symptoms, such that psychological symptoms have been shown to affect cognitive functioning in MS, with depression, in particular, having been identified as a potentially confounding factor.

3,4 However, to date, the impact of other mood indices, such as anxiety and stress, on cognitive function has received less attention.

Depression has been the most commonly evaluated psychological symptom in MS. Depressive symptoms have been reported in over 50% of patients with MS,

5 three times higher than in the general population, and they occur more frequently in those with progressive disease.

5 Depressed MS patients have been shown to have impaired memory, attention, and information- processing speed,

3,6,7 and studies have shown that subjective impairments in cognitive function reported by depressed patients with MS improve after antidepressant treatment, independent of changes in objective cognitive performance.

4,8In addition to depression, anxiety disorders are common in MS. The lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in MS has been estimated at 36%, which is substantially higher than the 5% seen in the general population.

9 Most constitute general anxiety disorders, whereas other common diagnoses comprise obsessive-compulsive disorder and panic disorders.

10 Other investigations of the point prevalence of anxiety disorders in MS patients have identified the occurrence of other related disorders including panic disorder, social phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder.

11Anxiety is seen more frequently in female patients with a comorbid diagnosis of depression.

10 Despite the high frequency of this symptom in MS patients, there is limited information regarding the impact of this symptom on cognitive function. A recent study

12 has suggested that MS patients with symptoms of state anxiety had greater impairment of attention and information-processing speed. Indeed, the effects of anxiety on cognition may well be more extensive, as studies of the effect of trait anxiety on non-MS individuals have shown effects on neural efficiency of working memory,

13 and induction of an anxious state can impede verbal and spatial memory.

14There is also a growing body of evidence to support an effect of stress on MS disease course.

15–17 Negative stressful events have been associated with an increase in MS lesion load,

15 while behavioral stress management strategies have been shown to reduce lesion formation.

16 A direct impact of stress on cognitive function in MS has not been widely examined, although altered cortisol release may be involved. Stress is known to enhance activity of the hippocampal pituitary adrenal axis, resulting in increased glucocorticoid release,

17 and dysregulation of this pathway has been demonstrated in MS patients.

18 In healthy individuals, a link between cortisol and long-term memory is seen,

17 and when cortisol function is impaired, as in posttraumatic stress disorders, memory function is affected.

19In the current study, we have undertaken a cross-sectional, retrospective study, in our MS outpatient clinic cohort, to examine the relationship between cognitive function and psychological symptoms. The frequency of depression, anxiety, and stress occurring in our patient group was evaluated. Using predictive statistical modeling, we explored the contribution of each mood index on cognitive performance to evaluate which symptom was having the greatest impact on cognitive function in our MS clinic cohort.

Results

The descriptive characteristics for the MS subtypes are shown in

Table 1. Seventy-nine percent of our cohort were classified as relapsing remitting (RRMS), 14% were secondary progressive (SPMS), and 7% primary progressive (PPMS) MS. Patients receiving MS-specific immunomodulatory treatments were predominantly RRMS patients and were receiving interferon beta (N=89), glatiramer acetate (N=42), natalizumab (N=25), fingolimod (N=9), dimethyl fumarate (N=4), or no MS immunomodulatory treatment (N=153) at the time of undertaking the study assessments. SPMS patients were older, had a longer duration of disease, and had a higher EDSS level than their RRMS counterparts at the time of the assessments. Using the severity grading criteria for each mood index on the DASS,

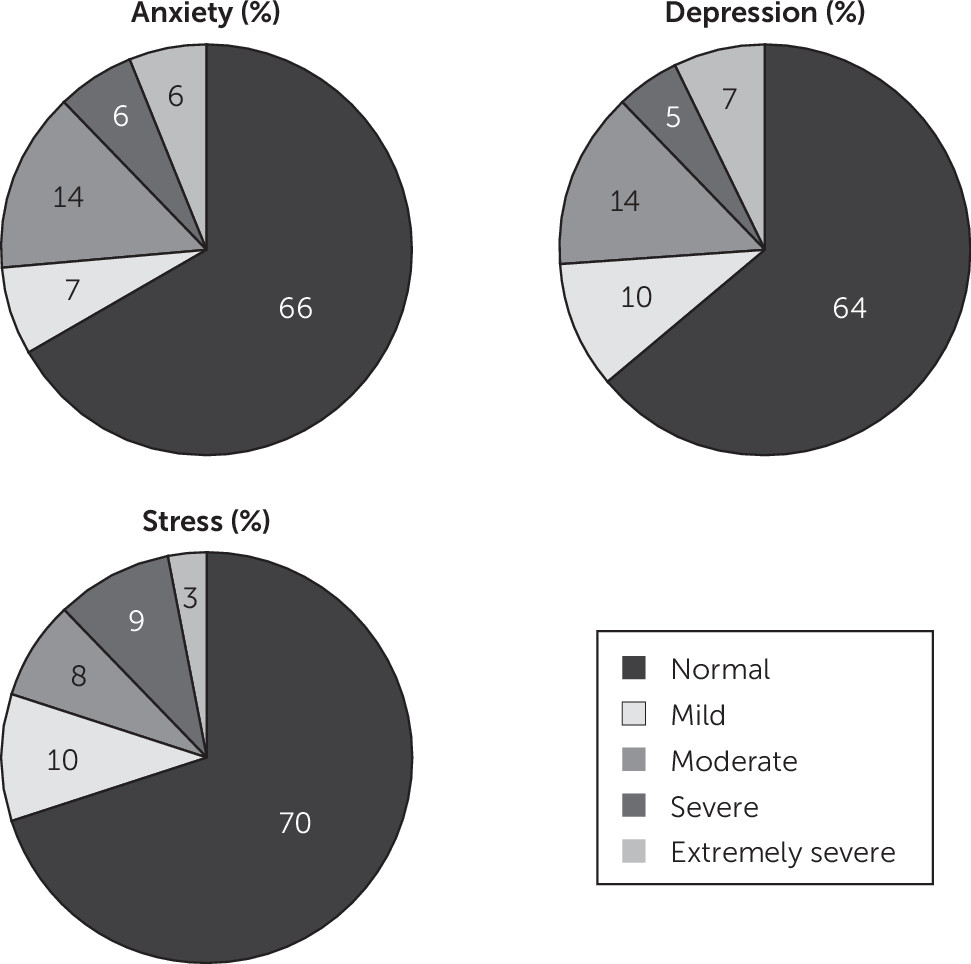

24 the severity of psychological symptoms was evaluated. In our MS cohort, 12% of patients reported severe or extremely severe anxiety, with 14% scoring moderate levels of anxiety (

Figure 1). Thirty-one percent were undergoing treatment with a serotonin reuptake inhibitor at the time of undertaking cognitive testing. Based on our definition of cognitive impairment (see above), 34% of our MS cohort were cognitively impaired.

There were several differences for the cognitive performance variables between MS subtypes (p<0.05). In general, at the group level, SPMS patients scored lower and PPMS patients higher for the overall ARCS score than those with RRMS. There were no statistically significant differences between MS subtypes for the mental health variables (p>0.1). While there was no significant difference between male and female patients for these variables, males tended to have lower average memory scores compared with females (p=0.07).

Cognitive performance variables (ARCS scores) were converted to Z scores for bivariate correlation and regression analyses (see the Methods section). Bivariate analyses showed widespread negative correlations between clinical variables and the cognitive performance variables (p<0.05) (

Table 2). The strongest negative correlation was observed between memory score and EDSS (r=−0.35, p=0.001). There was a general tendency for a lower cognitive performance, across all domains, to correlate with higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. The strongest individual mental health correlate of overall cognitive ability was anxiety (r=−0.27, p=0.004). Among the cognitive domains, anxiety also showed the strongest correlation with memory (r=−0.27, p=0.0005). The level of disability accumulation, as measured by EDSS, showed a weak correlation with both anxiety and depression indices (data not shown).

To assess the relative association of each of the mental health variables (depression, anxiety and stress) with cognitive ability in this MS patient cohort, we performed linear regression analyses factoring in these three main factors as well as relevant covariates. When analyzed separately, all three mood indices were significantly associated with overall cognitive performance, after accounting for significant clinical covariates (p<0.008). Interestingly, when we modeled all three mood indices together, anxiety was the only mental health variable that was significantly associated with cognitive function (

Table 3). After conditioning on stress and depression, increased anxiety scores were significantly associated with reduced cognitive performance (β=−0.22, p<0.008). These results indicate that the association of stress and depression with cognitive outcome is no longer statistically significant in this model after accounting for the association with anxiety. Analyses of cognitive subdomains showed that the association of anxiety appeared to exist across the different cognitive domains but was strongest for memory (β=−0.22, p<0.008). Of all regression models, the memory model yielded the highest explanatory value showing that, in combination with sex, age, and EDSS, anxiety explains 24% of the variance in memory domain (adjusted R

2=0.24, p<0.008).

Discussion

Recently, cognitive impairment has received increased attention by MS experts, and there is a trend to establish monitoring of cognitive deficits as part of routine clinical practice in MS clinics. It is important to consider the impact of other potentially confounding factors on cognitive function at the time of assessment. Of the psychological parameters that have been evaluated, there have been extensive reports detailing an association between depression and cognitive performance in MS patients.

3,4 Indeed, in our study we also see a relationship between the level of depression and cognitive function, with depression scores being inversely associated with performance on memory, fluency, and attention functional domains. In contrast, the impact of anxiety disorders in MS has received less investigation to date, despite their occurrence in about one third of patients.

9 In our clinic cohort of 322 MS patients, 26% reported anxiety of at least moderate severity. In a large study of patients with MS,

10 symptoms of anxiety were closely associated with suicide attempts. The finding that suicide is the cause of 15% of all deaths in MS'

26 highlights the need for routine monitoring of anxiety symptoms within this patient population.

We found that anxiety had a significant association with cognitive performance after accounting for the association of depression and stress, and this relationship among mood indices was consistent, regardless of the varying associations of the other clinical covariates. This suggests that in this cohort the association with anxiety may be of the highest relative importance for cognitive function among the three mood indices measured. To our knowledge, this is the largest study objectively assessing anxiety and its association with cognition in MS. This study is also unique in its assessment of the contribution of depression, anxiety, and stress on overall cognitive function, as well as five cognitive domains to evaluate which mood index has the most dramatic impact on cognitive performance in MS patients. Our findings support those shown by Goretti et al.,

12 in which the impact of psychological symptoms on cognitive impairment in 190 patients was evaluated. They showed state anxiety to be stronger than depression (or fatigue) as a predictor of cognitive function, when defining anxiety symptoms using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and depression by the Beck Depression Inventory. Delineation of anxiety disorder subtypes was not applied in the current study; rather the identification of psychological symptoms was by application of the DASS-21 self-report questionnaire. This approach enabled symptoms of anxiety to be identified at the time of undertaking the cognitive testing and provided findings comparable to those observed in a study by Goretti et al.,

12 in which anxiety was seen to be a stronger predictor of cognitive performance than depression. Our clinic cohort was comprised predominantly of RRMS patients (79%) with an average disease duration of 7 years but also included patients with a progressive disease phenotype (21%). This differed slightly from the Goretti et al.

12 study, which was restricted to RRMS patients with a longer average disease duration. However, the association of anxiety with cognitive performance is not restricted to RRMS cases, as in early MS and in clinical isolated syndrome, increased anxiety scores have also been associated with cognitive impairment.

27 In our study, we did not see any association between duration of disease with the magnitude of psychological symptoms, hence the severity of anxiety was seen to a similar extent in both the early stages and long-term disease.

The major association of anxiety with cognitive performance in our clinic cohort was with respect to memory and fluency. The cognitive testing battery we applied in our study was the ARCS, which—while it differs from those used by other investigators—is sensitive and obtains results consistent with those derived from a comprehensive assessment by a neuropsychologist and also correlates closely with the more commonly used tool SDMT.

22 Conceivably, utilization of different cognitive tests may account for differences in functional domains associated with anxiety seen in other studies. Goretti et al.

12 applied Rao’s Brief Repeatable Battery and found that state anxiety was associated with poorer performance on complex attention tasks and information-processing speed. Julian and Arnett

28 also demonstrated a stronger association of state anxiety than depression on cognitive function, particularly for tasks measuring “executive functioning” (the Shipley Vocabulary Test and Visual Elevator Subtest).

The mechanisms that underpin the association of increased anxiety with poorer performance on cognitive tests in patients with MS are not clear. A first, obvious possibility, is that with increasing lesion load, structures relevant to anxiety and cognition are both increasingly likely to be damaged.

29 Imaging studies point to the involvement of, and altered connectivity with, subcortical gray matter structures such as the amygdala, even relatively early during the course of MS.

30,31 A second possibility is that a patient’s perception of loss of cognitive or general functioning might make them anxious. In our study, the level of disability accumulation, as measured by EDSS, was correlated with the level of anxiety and depression, consistent with findings from a large online U.K. registry study.

32 Indeed, findings from the U.K. study suggest that physical disability is a major predictor of anxiety and depression in MS, although more subjective evaluations of disability were applied compared with the EDSS evaluations conducted in the current study. Clearly, the first mechanism mentioned could also account for these associations. Third, anxiety might have a more direct consequence for cognitive functioning, independent of any considerations of lesion load. In relation to this third mechanism, studies conducted in threat of shock studies or in non-MS anxiety disorders,

33 anxiety has been shown to affect attention, working memory, and executive function. The role of anxiety on working memory has also been supported by functional MRI (fMRI) in individuals with trait anxiety.

13 High signal in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and left inferior frontal sulcus on fMRI correlated with high levels of anxiety and was considered to be related to impairment in processing efficiency in these individuals. Fourth, anxiety has also been associated with other behavioral issues that themselves may affect disease outcome and cognitive performance in MS. Alcohol dependence and smoking have been associated with anxiety and depression in MS.

34 Such behaviors may in turn be potentially impactful on MS disease progression

35 and subsequently cognitive function. Finally, depression or anxiety disorders in MS have been linked to specific personality traits in individuals with MS to include those with more neuroticism, introversion, less agreeableness, and less conscientiousness.

36 These traits have been linked directly to impairment of cognitive function, with MS patients displaying low conscientiousness and high neuroticism having more brain atrophy, evidenced by reduced gray matter volume, and impaired information-processing speed.

37In addition to showing the association of depression and anxiety with cognitive performance, we also saw that stress correlated with cognitive function. However, the correlations between stress scores and cognitive domains were more modest than those for depression and anxiety.

Our study has some important limitations. Our measures of anxiety and depression were obtained by questionnaire and were not supplemented by any formal clinical diagnoses. Nevertheless, accepted cutoffs on the screening measures were used to define meaningful categories of severity. The cross-sectional nature of the study prevents us from making any causal inferences. Indeed, as we have indicated, the potential mechanisms of association between anxiety and cognition are numerous and complex. Although identification and treatment of anxiety (and depression) are clinically appropriate, we lack definitive evidence to suggest that such treatment would necessarily also benefit cognition. Our evaluation of the association of stress with cognitive function was also limited and did not enable an identification of the frequency or nature of stressful life events that may have occurred. These have been suggested by others to be key factors in understanding the impact of stress on MS symptoms and disease progression.

16In conclusion, depression, anxiety, and stress are highly prevalent in MS patients. Anxiety is significantly associated with cognitive performance, independent of depression in MS, and future studies are needed to determine whether treatment of anxiety also benefits cognition in these patients.