Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) was developed initially for patients with chronic pain conditions.

10,11 Since that time, it has shown benefits across a wide range of physical and mental health conditions. Published randomized control trials (RCTs) for mindfulness interventions increased from seven between 2001 and 2003 to more than 200 between 2013 and 2015.

12 In addition, 79% of medical schools now offer some variation of mindfulness training.

13 The most widely used evidence-based mindfulness interventions stem from Buddhist meditation practices, which focus on breaking maladaptive habits and increasing the experience of positive emotions.

14,15 MBSR served as a template for the later development of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP).

14,16,17 These secular mindfulness-based therapeutic interventions all share the goal of facilitating the development of the skills required to maintain a nonjudgmental awareness (e.g., accepting, open) while keeping attention focused on internal and external experiences occurring in the present moment.

14,18 That is: observing one’s own thoughts in the present moment with objective curiosity.

14,18 It is important to emphasize that mindfulness is not synonymous with relaxation and that relaxation is not the goal of mindfulness interventions. An article from Harvard Business Review in 2015 was titled, “If Mindfulness Makes You Uncomfortable, You’re Doing It Right.”

Development of mindfulness as a skill has been shown to have significant positive effects in both healthy community and clinical samples. Two recent meta analyses of studies assessing the effect of mindfulness interventions on groups of healthy individuals (e.g., undergraduate students, healthcare trainees, healthcare professionals, community members) reported moderate to large positive effects on multiple aspects of functioning (e.g., stress, anxiety, depression, quality of life).

19,20 Studies support significant benefit for persons coping with physical conditions, (e.g., cancer, chronic low back pain, fibromyalgia, and migraines), as well as persons suffering from mental health disorders (i.e., depression, substance misuse, sexual trauma, anxiety, general stress, and emotional dysregulation). As is generally true for clinical research, publication and reporting bias for positive trials are problematic, potentially over-stating the effects of mindfulness-based interventions.

21,22 Recent advancements have produced a standardized active control condition (i.e., an 8-week health enhancement program). If used consistently across RCTs, this could significantly decrease the surplus of confounding methodological variables.

12,23Recent reviews agree that mindfulness-based interventions are effective in improving many aspects of chronic pain (e.g., pain intensity, pain-related disability, quality of life, mental health issues).

12,24 Two recent meta analyses of 25 RCTs of mindfulness interventions in patients with chronic pain conditions (unspecified chronic pain, musculoskeletal pain, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis) support modest beneficial effects.

22,25 One meta-analysis identified RCTs that utilized either acceptance-based or mindfulness-based therapy.

25 Multiple outcome measures (pain intensity, pain interference, disability, quality of life, depression, anxiety) were examined. Pooled standardized mean differences indicated that modest improvements (small to moderate effect sizes) were found on most outcome measures at the end of treatment. Pain interference and anxiety were the most improved (moderate effect sizes). Notably, only five studies included comparison to an active control (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT], relaxation training). Mindfulness interventions were superior to relaxation (moderate to large effect size) for most outcome measures, including quality of life, pain interference, disability, and depression. CBT was somewhat better (small effect size) for depression, pain interference, and disability. Thirteen studies included follow-up data (ranging from 2 to 12 months). Effect sizes were greater on all outcomes except pain intensity at follow-up.

25 Both meta analyses raised concerns related to the considerable methodological heterogeneity across studies (e.g., sample make up and size, power, treatment length and adherence, comparison conditions, symptom measures).

22,25 Some of these methodological issues have been addressed by the most recent RCTs. A large RCT (initial N=282, 6 month follow up N=253) of older adults with chronic lower back pain comparing MBSR to a health education program of the same duration reported modest (small effect sizes) short- and longer-term benefits for pain measures (current, most severe). Improvements on functional measures were not sustained at follow up.

26 As noted by the authors, low levels of depressive symptoms at baseline and less-than-optimal treatment attendance limited generalizability of findings. Another large RCT (initial N=342, 52 week follow up N=290) in adults (20 to 70 years of age) with chronic (minimum 3 months) low back pain reported MBSR and CBT were both superior to usual care.

27,28 A significantly greater percentage of the MBSR and CBT groups had clinically meaningful improvements (minimum 30%) in the primary outcome measures (disability questionnaire, self-reported pain bothersomeness) at 26 weeks.

27 This difference was maintained at 52 weeks for the MSBR group. As noted in a related editorial, although participation in treatment was not optimal (only half of participants attended at least 6 out of the 8 group sessions), the findings support the value of these approaches for improving the lives of patients with chronic pain conditions.

29 The analyses comparing specific elements of therapeutic outcomes that have been proposed as mechanisms of change associated with MBSR (increased mindfulness and pain acceptance) or CBT (decreased catastrophizing and increased self-efficacy) found that none of the predictions were fully supported.

28 MBSR was significantly more effective in decreasing catastrophizing immediately post treatment and the interventions were similarly effective at 52 weeks. MBSR and CBT had similar benefits for self-efficacy immediately post treatment. Generally, no significant differences were observed between groups in pain acceptance and mindfulness. As noted by the authors, these results suggest that MBSR and CBT may be acting through similar therapeutic mechanisms.

28Although less studied, there is increasing evidence that mindfulness based interventions may be generally beneficial for other health conditions.

12,24 Recent systematic reviews indicate preliminary evidence for the treatment of primary insomnia, somatization disorder, irritable bowel syndrome, asthma, tinnitus, as well as potential improvements in select immune system processes.

23,30 A pilot study in Veterans with Gulf War Illness (defined as the combination of activity limiting fatigue, musculoskeletal pain in more than one area, and difficulty with concentration/memory) found MBSR plus usual care to be significantly more effective than usual care alone for improving all three symptom domains (medium to large effect size) by the 6 month follow-up.

31 Also promising are mindfulness based interventions in adult primary care settings.

32 A meta-analysis of six RCTs reported modest beneficial effects on general health, mental health and quality of life.

32 Although encouraging, the authors noted the need for better designed studies and long-term follow-up measures. Surprisingly, one RCT found that participants’ self-reported utilization of healthcare services during the study period did not differ between the mindfulness and usual care groups.

33 In contrast, studies based on administrative data capturing all healthcare services demonstrated marked decreases in health service usage following mindfulness interventions.

34,35Growing interest in mental health treatment incorporating mindfulness-based interventions has resulted in a surge of research encompassing a wide range of conditions, including mood, anxiety, psychotic, and substance use disorders.

12,15,24,36–38 Recent meta analyses of RCTs indicate that mindfulness-based interventions are effective for relapse prevention in patients with recurrent depression.

39,40 The meta-analysis (25 studies, follow up 17 to 332 weeks) that examined a range of psychological interventions (CBT, MBCT, interpersonal therapy) found that all were similarly effective in reducing relapse risk as compared with both treatment as usual and to maintenance antidepressant medication.

39 Similar results were reported in the meta-analysis that focused on MBCT (nine studies, follow up 60 weeks).

40 This study also reported preliminary evidence that MBCT might be more effective in patients with higher levels of residual symptoms prior to treatment. A meta-analysis of RCTs of mindfulness interventions (MBSR, MBCT) in patients meeting diagnostic criteria for current major depressive disorder or an anxiety disorder (e.g., social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder) demonstrated improvements (large effect size) in severity of primary symptoms for depressive disorder but not for anxiety disorders when compared with inactive control conditions.

41 A health economics analysis found that provision of MBCT for Australian patients with recurrent depression receiving specialist mental health care was cost effective, as reductions in other health care costs (e.g., hospital services, ambulatory care) were greater than the cost of providing MBCT.

42Mindfulness interventions may have potential for treatment of anxiety disorders. Reviews indicate that even internet-based mindfulness interventions can be beneficial.

43,44 A systematic review of mindfulness intervention studies for social anxiety disorder (SAD) found mindfulness based treatments to be effective, though not superior to CBT.

45 A more recent RCT in patients with SAD focused on the effects of group CBT versus group MBSR.

46 Results suggest that CBT and MBSR were equally effective in reducing symptoms and maintaining treatment gains at one-year follow up. Contrary to expectations, mediation analyses identified mostly shared psychological mechanisms of change for CBT and MBSR (i.e., decreased cognitive distortions and safety behaviors, increased reappraisal frequency, mindfulness skills, and attention focusing). A systematic review of mindfulness intervention studies for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) found preliminary evidence that mindfulness-based treatments may be effective, although more methodologically rigorous studies are needed.

47 A secondary analysis of four MBSR trials in Veterans with PTSD came to similar conclusions.

48 Promising results were also reported for a brief (four session) mindfulness intervention for PTSD delivered within primary care.

49 Mindfulness interventions may also be a useful alternative psychological treatment for comorbid conditions. A recent pilot study in Veterans with comorbid PTSD and mild traumatic brain injury found MBSR to be beneficial for both conditions (improving attention and decreasing PTSD symptoms).

50 Positive aspects of this treatment in comparison to others included absence of adverse effects and high levels of acceptability. Veterans reported that the offering of diverse mindfulness exercises (e.g., body scan, yoga) was particularly helpful, as it presented a higher likelihood that at least one exercise would resonate with each individual.

Potential mechanisms of action have been evaluated in both a meta-analysis and a systematic review.

51,52 Mediation analyses testing potential mechanisms of action for mental health outcomes (clinical and nonclinical populations) found moderate to strong evidence for improved cognitive and emotional reactivity, higher mindfulness, and decreased repetitive negative thinking (e.g., rumination, worry).

51 Mechanisms of action in patients with recurrent major depression identified by multiple studies included increases in mindfulness-related skills (e.g., meta awareness, self-compassion) and decreases in negative thinking.

52 Thus, it appears that mindfulness training is effecting fundamental cognitive processes, such as distress tolerance, cognitive and emotional reactivity, and emotional regulation.

51,53Although multiple reviews and meta analyses have identified a broad range of structural and functional brain differences associated with meditation practices, most studies are not directly relevant to understanding the neural correlates of secular therapeutic mindfulness interventions.

54–56 The majority of studies are cross sectional (e.g., comparing long-term meditation practitioners to meditation-naïve individuals). This makes it very difficult to adequately control for the multiple factors differing between groups that have the potential to greatly affect brain structure and function. In addition, some studies combine very different types of meditation practices. Two recent meta analyses that were designed to identify the neural correlates of mindfulness meditation (defined either as open monitoring or as Buddhist inspired meditation) had only a few areas of agreement.

57,58 More informative for clinical practice are longitudinal studies that assess change within an individual by obtaining measures both prior to and following a mindfulness intervention. Studies in healthy individuals have potential to provide insight into intervention-related neurobiological changes but may not be directly informative about mechanisms for therapeutic change. These are best addressed by longitudinal studies in specific clinical populations.

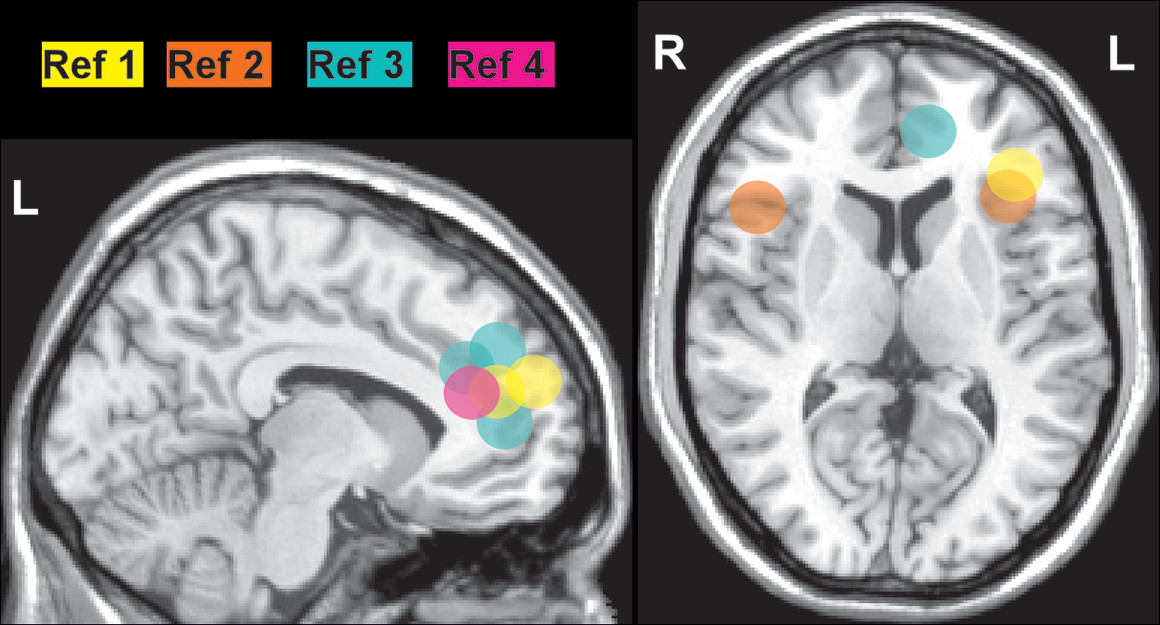

Several small studies have utilized functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) with emotional tasks (e.g., emotional faces, self-referential negative and positive words, self-referential negative and positive beliefs) prior to and following mindfulness interventions in patients with anxiety disorders (SAD, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD) to identify clinically-relevant training-related changes. Areas of convergence across studies include increased posttreatment activations in dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (PFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and ventrolateral PFC/anterior insula that correlated with symptom reductions (

Figure 1).

1–4 As noted by the authors of these studies, the results support treatment-related enhanced recruitment of areas contributing to emotional processing and regulation of emotional responding. Changes in the amygdala have also been reported. A study of patients with generalized anxiety disorder reported posttreatment normalization (decreased activation) of the amygdala response to neutral faces.

2 Task-related functional connectivity of the amygdala with several areas (medial PFC/ACC, dorsolateral PFC) switched from negative (anticorrelated) to positive (correlated); these changes correlated with symptom improvement.

2 A study in community adults reported that higher past month stress was associated with higher resting state connectivity between the amygdala and subgenual ACC (whole brain analysis).

59 Resting state connectivity between these structures was decreased in the highly stressed subgroup (job-seeking unemployed) following an intensive (three day residential) MBSR intervention.

59 In contrast, a study of patients with PTSD reported increased amygdala response to angry faces posttreatment that correlated with symptom improvement.

3 Both task-related and resting state functional connectivity from the amygdala to the medial PFC (and other areas) increased, but these changes did not correlate with symptom improvement.

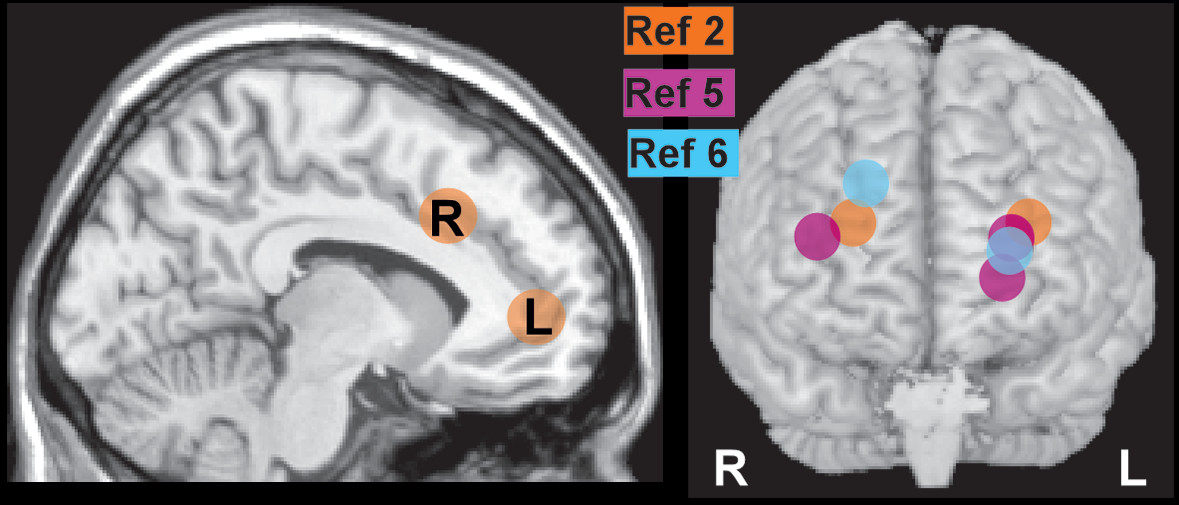

3,5 However, increased posttreatment resting state functional connectivity between the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and dorsolateral PFC correlated with decreases in both the avoidant and hyperarousal symptoms clusters (

Figure 2).

5 The study in highly stressed community adults (job-seeking unemployed) also reported increased resting state connectivity between PCC and dorsolateral PFC following an intensive MBSR intervention.

6 As noted in both studies, these results are consistent with training-related improvement in voluntary control of attention (top-down executive control) contributing to improved emotional regulation. Overall, these findings indicate that standard clinical mindfulness interventions may exert therapeutic effects by altering the state of specific brain regions (as indicated by changes in task-related activations) and brain networks (as indicated by connectivity changes).

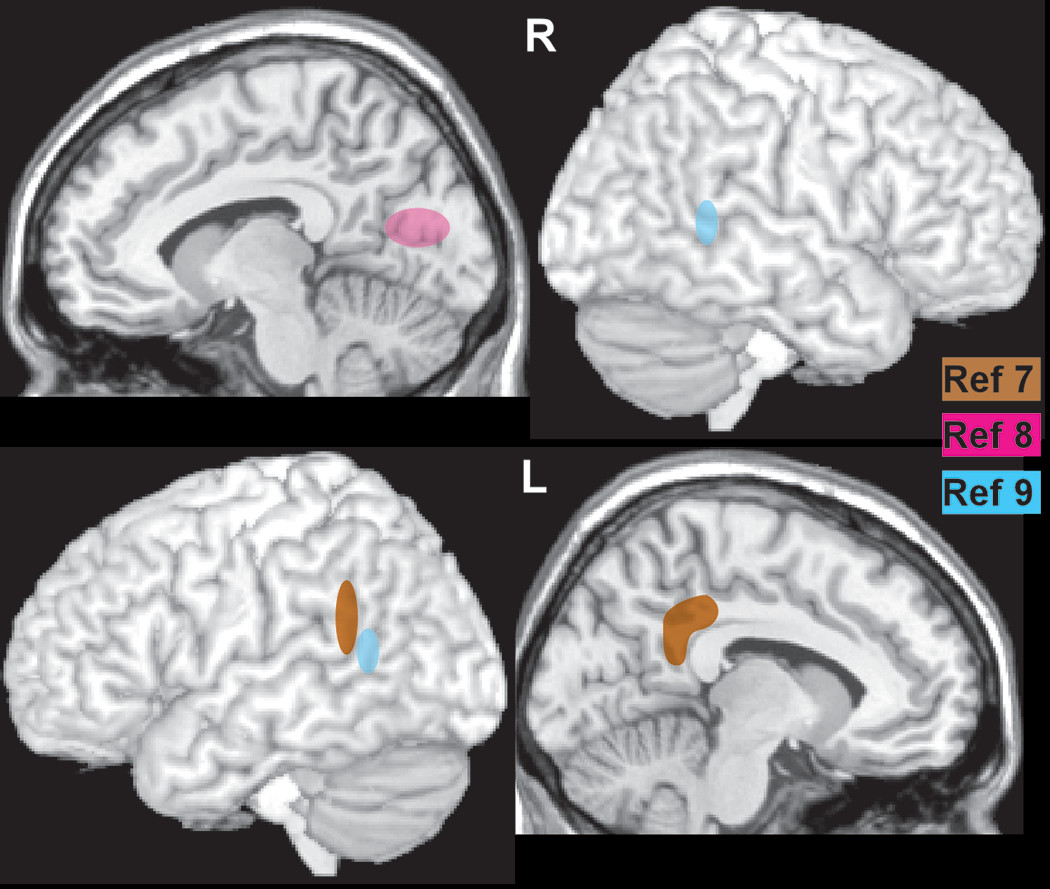

Only a few longitudinal studies have utilized voxel based morphometry and exploratory whole brain analyses to identify areas of structural change (gray matter density, gray matter concentration) associated with a standard mindfulness intervention (e.g., 8 weeks of MBSR), mostly in healthy individuals. There are only a few areas of convergence across studies (

Figure 3). One study reported increased gray matter concentration in PCC, temporoparietal junction, cerebellar vermis/brainstem and lateral cerebellum following MBSR, whereas there were no areas of significant change in the control group.

7 In a subset of participants in which a measure of psychological well-being was obtained prior to and following MSBR, percent change in well-being scores correlated with percent change in gray matter concentration in bilateral clusters in the pons (area of the locus coeruleus).

60 A pilot study of a 6-week mindfulness intervention (Mindful Awareness Practices for Daily Living) in older adults with sleep disturbances (Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index >5) reported increased gray matter in precuneus and decreases in prefrontal and parietal areas, hippocampus, and thalamus following the intervention.

8 A small RCT of MBSR in patients with Parkinson’s disease reported increased gray matter density in the caudate, thalamus, temporoparietal junction and occipital lobe following MBSR, whereas the two areas of significant increase in the control group were in the cerebellum.

9 Although preliminary, these studies support the possibility of rapid initiation of structural brain changes by standard clinical mindfulness interventions.

In conclusion, there is a growing body of evidence supporting the helpful effects of secular mindfulness interventions for improving a wide range of fundamental processes in both physical and mental disorders. There is still much to be learned regarding the underlying neurobiological processes of therapeutic change. Longitudinal fMRI studies in specific patient populations will be particularly useful to elucidate similarities and differences across disorders.