To date, little is known about the dyslexic characteristics in Chinese-speaking patients with svPPA. Chinese is a logographical language that carries distinctive linguistic characteristics when compared with alphabetic languages such as English. Individual characters in the Chinese writing system are formed by basic graphic units. Each character represents the smallest unit of meaning and is monosyllabic.

4 Simple characters, made up of various spatial arrangements of strokes, can combine to form logographemes/radicals.

5 Approximately 80%−90% of Chinese characters are ideophonetic compounds, formed by phonetic and semantic radicals, providing the pronunciation and the meaning of the character, respectively.

4,6 Only a very small portion of simple characters are pictographic in nature. Some authors propose that Chinese characters consist of three levels of regularization with regard to the relationship between shape and pronunciation: regular, semiregular, and irregular. In regular characters, the character is pronounced as a whole in the same manner as its phonetic radical (e.g., “座”/zuo4/, with the phonetic “坐”/zuo4/). In semiregular characters, the phonetic radical provides partial information about pronunciation (e.g., “精”/jing1/ and its phonetic “青”/qing1/). In irregular characters, the pronunciation of the character is different from its phonetic radical (e.g., “埋”/mai2/, with the phonetic “里”/li3/).

7–9 As such, the Chinese language is considered an opaque language.

4,7,8 However, other researchers have provided evidence that phonological awareness is reported to be comparatively less important in Chinese compared with other opaque languages

10–12; instead, reading proficiency is related to other cognitive abilities such as orthographic awareness, visual skills, and morphological awareness.

10,11In view of the absence of phonemes that are associated with letters, some scholars believe that Chinese has no GPC as per alphabetic language.

13–16 Studies have attempted to classify children with developmental Chinese dyslexia according to a dual-route model but with inconsistent and controversial results,

4,9,17 unlike studies investigating alphabetic languages such as English and French, in which classifications of dyslexia with phonological and surface patterns were consistent.

18–23 In order to overcome the dual-route model controversy when classifying Chinese dyslexia, Yin and Weekes used a similar concept called “the triangle model of Chinese reading,” which includes a lexical-semantic pathway that allows phonological output to directly access orthographical representation.

24 However, this model still poses limitations with regard to surface-like error finding when reading irregular Chinese words, probably because of the different fundamental linguistic characteristics of phonological processing between Chinese and English. The aforementioned highlights the limitation and controversies of heterogeneity findings of current Chinese reading models.

Discussion

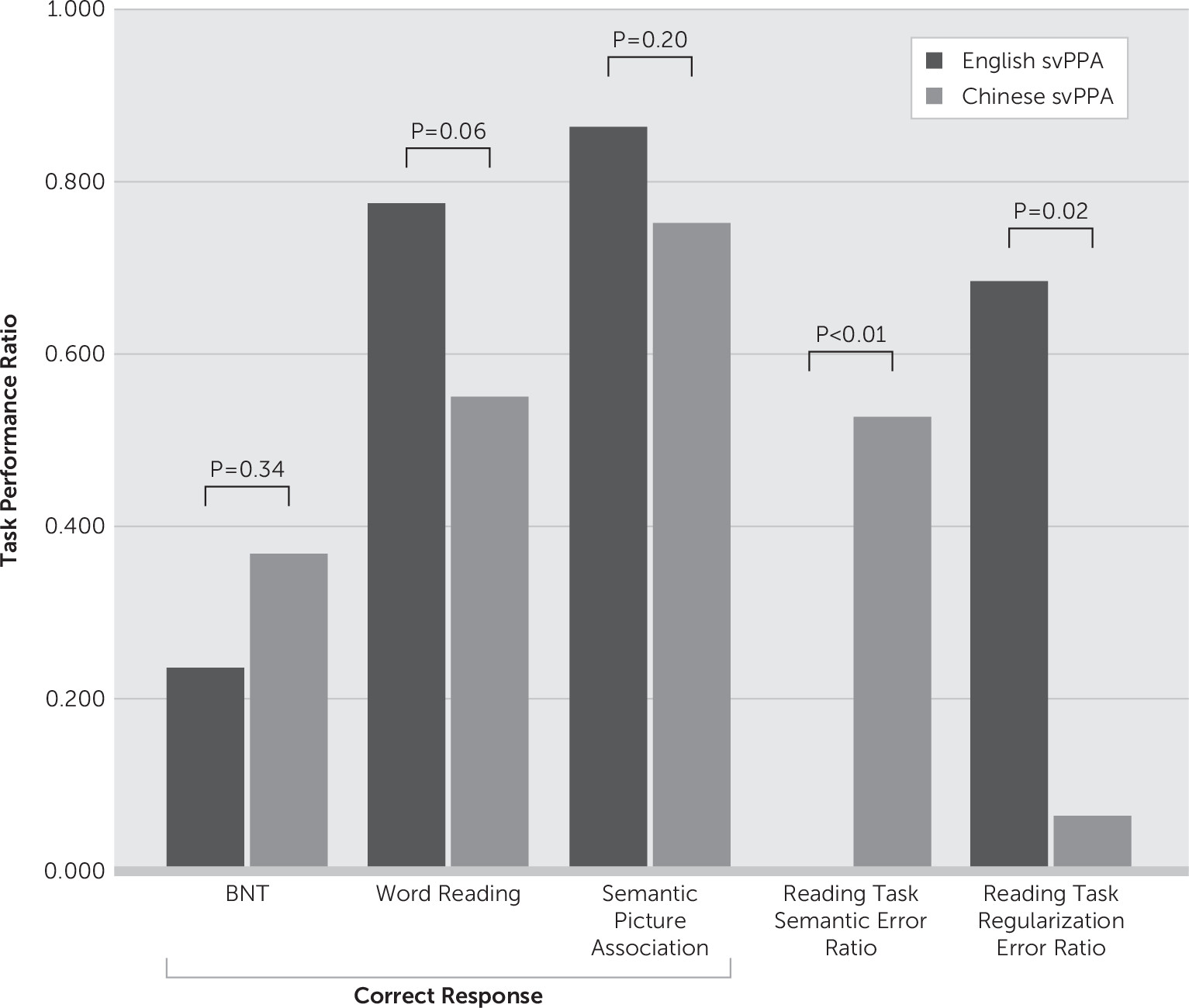

Consistent with our previous case reports,

28,29 the most important and interesting finding of the present study is the significant semantic-related dyslexic error observed only in the Chinese-speaking patients with svPPA. The statistically comparable Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) and semantic picture task performance rate suggested that the two groups of patients probably shared a similar stage in clinical severity of the disease. Unfortunately, because of the small sample size, multivariate logistic regression models could not be generated; hence, the results were not able to be adjusted for years of education. However, the complete absence of any semantic error in the English-speaking group but relatively high incidence rate in the Chinese-speaking group suggests that the observation is likely valid.

Current literature recognizes a dual-route psycholinguistic model of reading consisting of a lexical route and a sublexical route.

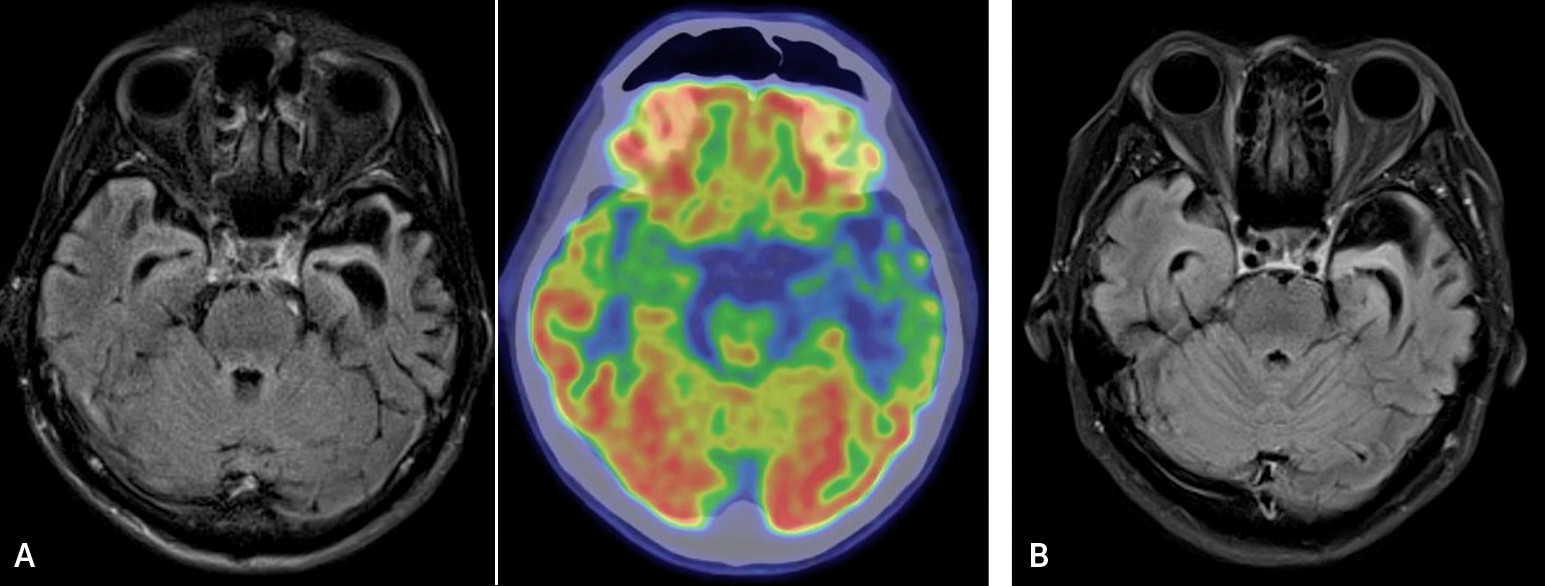

33–36 Several functional studies also support the existence of such routes, which include the ventral-lexical sound-to-meaning pathway extending from the occipital-temporal-frontal region and the dorsal-sublexical sound-to-print pathway extending from the occipital-parietal-frontal region. Ventral pathway impairment typically presents as failure to read irregular words, as phonological output of these words is directly imprinted into the orthographical representation in this pathway. Meanwhile, dorsal pathway impairment presents as failure to read morphologically complex words as a result of impairment of the print-to-sound or GPC mechanism.

37–42Lesions in the ventral route result in an overreliance on the dorsal route and produce surface dyslexia, or regularization error. However, patients retain the capability to sound out pseudowords. On the other hand, dorsal route impairment produces phonological dyslexia, characterized by the capability to read concrete words but not pseudowords or words with low semantic value such as function words (e.g., “it,” “the”), signifying an overreliance on the semantic system. A recent behavior-lesion correlation study by Ripamonti and colleagues demonstrated consistent findings that surface dyslexia is predominantly associated with left temporal lesions and phonological dyslexia at left insula and the left inferior frontal gyrus (pars opercularis).

43Semantic-related dyslexic error, or deep dyslexia, which in literature has been mainly described in alphabetic languages such as English, is perhaps the most extensively studied type of central dyslexia.

44 The term

deep dyslexia was designated by Marshall and Newcombe when they described a patient (G.R.) with a tendency to produce errors that appeared to be semantically related to the target words.

34 The failure to produce a phonologically matched but semantically relevant response suggests an impairment of processes mediating the access of stimuli to the visual word form system.

45 The current literature mainly describes this phenomenon in alphabetic languages, with deep dyslexia largely being observed in the left hemisphere, especially in relation to large perisylvian lesions extending to the frontal lobe.

44 Deep dyslexia is generally seen in patients suffering from nonfluent dysphasia, such as left middle cerebral artery infarction, which, so far, has not been associated with any neurodegenerative language disorder, particularly in alphabetic-language speakers, such as English speakers. The postulation of producing such response has been inconclusive, with no clear consensus among experts. While some experts suggest that residual left hemispheric function is responsible for producing such erroneous responses, Coltheart

46 proposed that it could, in fact, be due to underlying right hemispheric regions attributed to reading. Generally, deep dyslexic semantic errors are observed when phonological impairment prevents patients from using the surface route/GPC route and limits them to using a deep, direct route; hence, to be prone for erroneous responses with production of semantic errors.

Literature describing acquired dyslexia in the Chinese language remains sparse to date, which may be due to the different mechanisms underpinning such phenomenology. Current studies of the lesioned brain and physiological functional study models support the notion that Chinese language is processed distinctively when compared with alphabetic languages, such as English.

7,28,29,47–50 It is demonstrated that orthography in Chinese is more important in accessing semantics than phonology

47,49 and that phonology processing in Chinese is distinctive when compared with alphabetic languages.

48 While most studies describing Chinese deep dyslexia used a model with a developmental approach, Shu and colleagues, as well as Yin and Butterworth,

7,50 described cases with deep dyslexia that involved either trauma- or vascular-related brain lesions, which were explained well by the triangle model. However, most patients suffered more diffuse and less well localized lesions; thus, determining a more precise brain-behavior correlation was challenging.

Current literature suggests the temporal pole as the convergence region for semantic knowledge. Recent studies have also implicated it in lexical-semantic processing. For instance, Busigny et al.

51 suggested a case for lexico-facio-semantics disassociation, secondary to a dysfunction in the left anterior temporal lobe. Abel et al. provided neurophysiological evidence that the left and right anterior temporal lobes showed a robust beta-band during visual naming of famous people and tools.

52 In studies investigating the temporal lobe in language processing in PPA, Wilson et al. demonstrated that its role in sentence processing is likely to relate to higher level processes such as combinatorial semantic processing,

53 while Migliaccio and colleagues demonstrated its role in the binding of lexical and semantic information in a bidirectional manner.

54 As Chinese is a logographical language in which semantic data are tagged to each individual character, we speculate that this region also serves as a center of convergence of lexical semantics of the language, particularly in logographical languages. Taking into account the current existing evidence mentioned earlier, it is possible that this region may mediate the semantic relevance of orthographical representations, in this case, observed via an impaired nonsemantic reading pathway.

Another finding in this study is the presence of surface dyslexia in both groups. However, regularization error, or surface dyslexia, was statistically more significantly observed in the English-speaking group. This is consistent with current literature suggesting a dual-route model in reading for alphabetic languages, in which patients with svPPA exhibit an overreliance on the dorsal GPC route, which produces regularization error. While Chinese is considered an opaque language, with regularization errors described in patients with both developmental and acquired dyslexia,

9,27 Weekes and Chen predicted, on the basis of the triangle model, that the presence of surface-like dyslexia is attributable to selective damage to the lexical semantic pathway; this type of error is also described as the legitimate alternative reading of components (LARC),

55 which was originally described in Japanese speakers.

56 In view of the different linguistic characteristics between English and Chinese, as discussed earlier, it is not surprising to observe a much higher rate of surface dyslexia in the English-speaking group. This is consistent with a neurophysiology study suggesting that the more predominant ventral route functions were used when reading Chinese.

57 This is also consistent with our previous observation of Chinese-speaking patients with semantic dementia, in whom regularization error was not the most profound dyslexic finding.

28,29Our findings of predominant deep dyslexia with a milder form of regularization errors appeared consistent with the current disease model of acquired dyslexia in Chinese-speaking patients with lesions, most profoundly at the temporal lobe, which is at the ventral route of the dual-route reading model. These results are probably best explained by the triangle model. The surface-like errors observed in this study could be a result of impairment of semantic knowledge, and more common pronunciations of components would dominate computation of phonology from orthography via the lexical nonsemantic pathway as proposed by Yin and colleagues.

16The strength of this study lies in being the first case series describing such a clinical phenomenon, but the significant limiting factors are due to the small sample size. The complete absence of deep dyslexic errors in the English-speaking group also poses challenges for generating a multivariate regression model. Future studies should look into multicenter collaborations, in view of the relatively rarity of the disease itself, and a more consistent or unified clinical approach for better comparison. Further investigation of the performance of Pinyin, particularly in bilingual cases, should also be considered in the future.

Our present study has a few important conclusions. First, the language-finding function in neurodegenerative disorders is likely dependent on the characteristics of the patient’s dominant language. Second, the left temporal pole could possibly act as a convergence center that mediates lexical semantics in logographical languages.