Catatonia is a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by particular motor and behavioral signs and symptoms

1 that can manifest as a consequence of many neurologic, psychiatric, and/or general medical conditions.

2–4 Research studies have found the prevalence of catatonia to be 5%−18% on inpatient psychiatric units,

5–8 12% in drug-naïve patients with first episode psychosis,

9 3.3% on a neurology/neuropsychiatric tertiary care inpatient unit,

10 3.8% on the intensive care unit,

11 1.6% to 1.8% on psychiatry consultation-liaison services,

12,13 and 8.9% in elderly patients referred for psychiatric consultation.

14 Depending on which catatonic signs are more prominent on exam, catatonia can be classified into retarded, excited, or mixed type.

5,15Several studies have found that psychiatrists and other physicians significantly tend to under-recognize catatonia. A prospective study found that research teams identified catatonia in inpatient psychiatric floors at a 9:1 ratio compared with routine clinical psychiatric services.

7 A retrospective chart review identified 18 case subjects out of 101 meeting criteria for catatonia in an inpatient child and adolescent psychiatric unit, and only two of these case subjects were properly diagnosed with catatonia.

16Another study in the general hospital identified catatonia in older adults referred for psychiatric consultation, and in none of those 10 cases did the consulting physician raise catatonia as a concern or indication for the consult.

14 A study found that catatonic signs were frequent in patients diagnosed with brain hypoxia, but a diagnosis of catatonia was never made.

17 In an educational needs assessment study by our group, significant knowledge gaps about catatonia were identified in resident physicians, more so for internal medicine residents compared with psychiatry residents.

18Catatonia and delirium are both causes of altered mental status in medical inpatients,

19 and recent studies have found high comorbidity between them.

20 A prospective study using the

DSM-521 criteria and validated catatonia rating scales found that catatonia was present in at least 12% of patients with delirium.

22 In a recent study, 81% of the cases of catatonia due to a neurologic condition were also diagnosed with delirium,

10 and according to a study by our group, the suspicion of comorbid delirium is the main driver of physicians ordering a more thorough medical workup for patients with catatonia.

23Current literature suggests that the diagnosis of catatonia is challenging because it requires physical examination

24 and clinical suspicion.

25 Some research studies have found a high discriminating value of the

DSM-IV criteria for the detection of catatonia,

1,9 and the Bush Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS) continues to be the most commonly used validated scale for the characterization of catatonia.

26,27Catatonia is known to be often reversible when adequately detected and treated with lorazepam and/or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT),

5,28 but its under-recognition and subsequent lack of treatment might lead to dangerous medical complications.

29,30 Moreover, the treatment with antipsychotics is associated with an increased risk for development of malignant catatonic features or neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) in patients with catatonia or a history of catatonia.

31 Thus, awareness about catatonia for all clinicians is relevant to improve patient care. Recently, guidelines for preventing common medical complications of catatonic states have been published.

32To date, no studies have systematically studied whether catatonia is under-diagnosed in the general hospital and what factors might be contributing to under-diagnosis. Here we present a retrospective study that explores whether cases of catatonia were not diagnosed in a general hospital, examines potential clinical factors contributing to under-diagnosis, explores differences in management, and investigates for potential consequences in clinical outcomes related to under-diagnosis.

Methods

An initial study by our group

23 detected 54 cases of inpatients who were diagnosed with catatonia by the treating clinicians and met

DSM-5 criteria for catatonia retrospectively at the University of Chicago between 2011 and 2013. After institutional review board approval was obtained, another retrospective chart review was conducted of all adult inpatients at the University of Chicago between 2011 and 2013. In order to obtain charts with potentially under-diagnosed catatonia, we ideated a list of 38 keywords describing catatonia-related signs and used the electronic medical record to select the cases for review.

The presence of three or more distinct keywords describing catatonic-related signs in the progress notes was used to identify cases for review. Charts were reviewed for evidence of catatonia during hospital admission by use, retrospectively, of DSM-5 criteria. Case subjects with a documented clinical diagnosis of catatonia were not reviewed again, since they were already included in the diagnosed group.

Initially, authors J.R.L. and M.M. reviewed separately all the notes of the selected charts to see if the case was a possible episode of catatonia as described by the DSM-5. During the initial chart review, the words echolalia and echopraxia were also searched in every chart, since they define DSM-5 criteria and had not been included in the initial list of catatonia-related keywords. All cases in which at least one reviewer identified possible catatonia were reviewed again independently by authors J.R.L. and M.M. in order to detail the DSM-5 criteria met during the episode. Only case subjects with three or more documented DSM-5 criteria were included in the study.

Each reviewer used a standardized sheet and only attributed the clinical signs to catatonia when there was no alternative better explanation. For example, the presence of grimacing documented to be related to pain, mutism due to aphasia or intubation, stupor due to coma, and decerebrate or ictal posturing were not considered to be signs of catatonia. Sociodemographic and clinical data, including the total number of Bush Francis Catatonia Screening Instrument criteria met, were obtained for all case subjects who met inclusion criteria.

Statistical Analysis

We first ran a series of univariate analyses to explore what factors significantly differed between diagnosed and under-diagnosed cases. T-tests were used to compare continuous variables, and Chi-square tests or Fisher exact test were used to compare discrete variables between the diagnosed and the under-diagnosed groups. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to look for differences between the groups in variables not following normal distribution (e.g., total number of catatonic signs). The univariate results were followed up with a multiple logistic regression predicting under-diagnosis of catatonia to test which factors remained statistically significant after controlling for other potential factors. Finally, analyses examined whether under-diagnosis was related to treatment and/or to clinical outcomes.

Results

Selection of Charts

Fifty-four case subjects had a diagnosis of catatonia and were included in the diagnosed group, and 1,082 had three or more catatonia-related keywords and had not been diagnosed.

Table 1 presents the frequencies of catatonia-related keywords among the 1,082 charts with three or more catatonia-related keywords. After initial review, 276 cases were flagged by one or both reviewers as potential catatonia cases, with an agreement rate of 79%. After final review, 79 cases that had not been previously diagnosed were found to meet three or more

DSM-5 criteria for catatonia retrospectively, and were classified as the under-diagnosed group.

Table 2 presents examples of catatonic signs that were not attributed to catatonia by the treating clinicians.

Clinical Characteristics and Differences Between the Groups

Characteristics of the groups in our study can be found in

Table 3. The characteristics of the diagnosed group have been previously published.

23 Univariate comparisons showed that, compared with diagnosed cases, under-diagnosed cases were significantly older (p<0.001), less likely to be African American (p=0.007), more often evaluated by neurology or neurosurgery services (p<0.001), less often evaluated by psychiatry service (p<0.001), more likely to be seen in medical inpatient settings versus the emergency department (p<0.001), had retrospective etiology of catatonia more often attributed to medical conditions (p=0.002), and had higher proportion of EEG tests completed (p<0.001) and abnormal EEG results (p=0.016). The presence of grimacing (p<0.001), agitation (p=0.025), and echolalia (p=0.008) symptoms were more common in the under-diagnosed group.

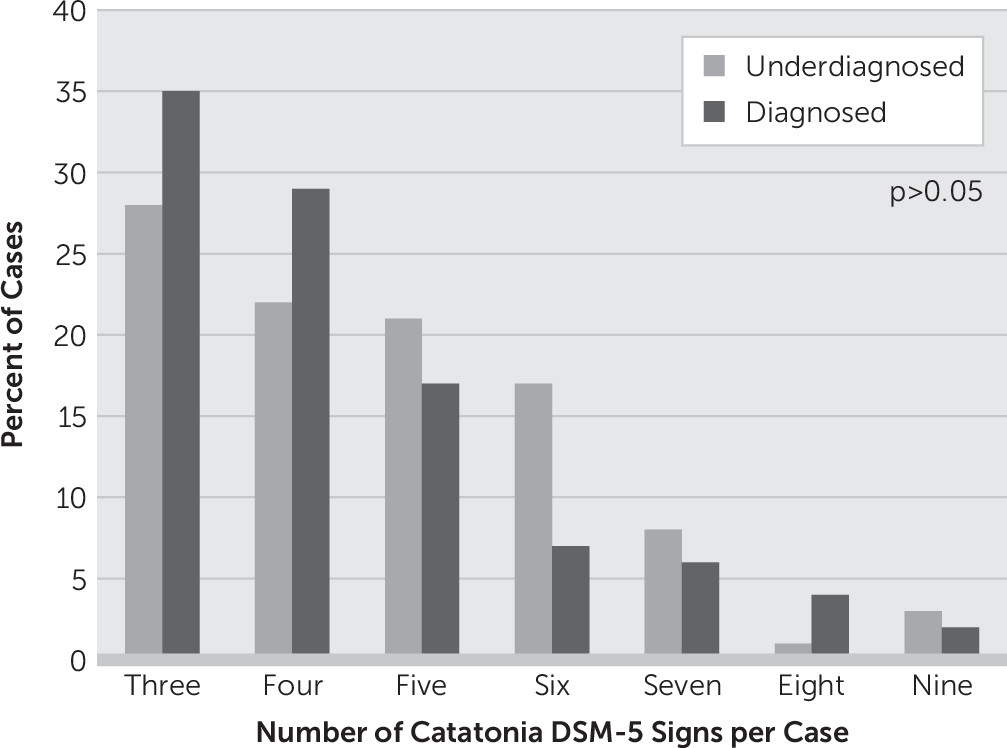

In contrast, under-diagnosis of catatonia was not related to presence of suspected delirium (p=0.605) or NMS (p=0.240) and there were no significant differences in the distribution of the number of catatonic signs between the groups (U statistic 19.5; p=0.569), as shown in

Figure 1.

Multiple Logistic Regression Predicting Under-Diagnosis of Catatonia

Multiple logistic regression analysis was next conducted using predictors that were significant at p<0.05 in the univariate comparisons (

Table 4), with the exception of abnormal EEG results. This variable was excluded given that case subjects who did not receive the test (N=51, 38.3% of the sample) necessarily had missing data. Results revealed that the presence of a psychiatric consultation during the episode significantly decreased the likelihood of under-diagnosis of catatonia (odds ratio [OR]=0.02, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.01–0.11, p<0.001), while the presence of grimacing (OR=6.56, 95% CI=1.86–23.16, p=0.004), agitation (OR=5.53, 95% CI=1.25–24.49, p=0.024), or echolalia (OR=4.33, 95% CI=1.32–14.24, p=0.016) significantly increased the likelihood of under-diagnosis. Age, race, setting, EEG testing, neurology or neurosurgery evaluation, and etiology of catatonia did not significantly predict under-diagnosis after controlling for other factors.

Treatment and Clinical Outcomes

Treatment characteristics and clinical outcomes for the groups can be found in

Table 5. None of our study case subjects received ECT. Univariate comparisons showed that no differences were found in rates of lorazepam treatment between the groups, with 50% of the sample not receiving any lorazepam. Among those who received lorazepam during the admission, total doses received were significantly lower in the under-diagnosed group (mean=0.4, SD=0.5 mg/day versus mean=1.3, SD=1.3 mg/day, p=0.004). The use of standing lorazepam treatment was also significantly less frequent in the under-diagnosed group (5% versus 28%, p<0.001).

Higher mortality rates during admission in the under-diagnosed group nearly reached statistical significance (13% versus 4% p=0.061, one-tailed). For those case subjects in our sample who were admitted to the general hospital as inpatients (N=105, 33 diagnosed and 72 under-diagnosed), higher length of stay in the under-diagnosed group fell short of statistical significance (mean=21.5, SD=20.2 days versus mean=15.9, SD=14.3 days, p=0.087, based on t test with log-transformed data).

Discussion

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to estimate the proportion of under-diagnosed catatonia in the general hospital and to find potential factors contributing to the under-diagnoses. Of the 133 case subjects who retrospectively met three or more DSM-5 criteria for catatonia in the general hospital over a 3-year period, the majority (N=79, 59%) were not diagnosed with catatonia during admission. Under-diagnosed catatonia was more frequent in the presence of agitation, echolalia, or grimacing; conversely, completion of a psychiatric consultation during the episode substantially decreased the likelihood of under-diagnosis of catatonia.

Case subjects meeting

DSM-5 criteria for catatonia retrospectively who received a psychiatry consultation during admission had greater than 44 times the odds of being diagnosed with catatonia compared with those who did not receive psychiatric consultation. This finding supports the crucial role of psychiatry consultation teams in detecting catatonia in the general hospital. However, more than one-third (37%) of under-diagnosed case subjects in our sample did receive a psychiatric consult, which suggests, in agreement with previous literature,

7,16 that under-recognition was frequent among case subjects evaluated by the psychiatry team and supports the need for greater recognition of catatonia across disciplines.

Our findings also suggest that under-recognition of catatonia may relate to physician unawareness of the heterogeneous cluster of signs and symptoms that constitute this syndrome. In particular, this study is the first to suggest that clinicians might often not consider agitation, grimacing, and echolalia to be attributable to catatonia. While these results warrant replication in other studies, there is indirect partial support for our findings from prior literature. A study of drug-naïve patients with first-episode psychosis found that agitation and grimacing were the signs of catatonia least correlated to other catatonic signs,

9 and case reports have shown under-detection of catatonia in agitated patients.

33,34 Thus, clinicians should be aware of the possibility of unexplained agitation being secondary to an underlying catatonic state.

The prevalence of grimacing and echolalia also independently predicted under-diagnosis of catatonia. One explanation for these results is that these clinical signs may be more likely than other signs of catatonia to be attributed to other conditions. For example, grimacing is a common clinical sign for pain, and treating physicians may attribute it to other medical conditions and not recognize it as a symptom of catatonia in their differential diagnoses. Echolalia is found in multiple neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism, dementia, and Tourette’s syndrome.

Of note, one study

35 reviewing the clinical characteristics of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) presentations found that echolalia, mutism (defined as aphasia/interrupted speech in the study), automatisms, catalepsy, staring, and increased tone are frequent features in patients with NCSE. Thus, NCSE seems to share clinical features with catatonia, in that it presents frequently with delirium in the elderly and tends to respond to treatment with GABA A receptor agonists such as lorazepam or midazolam. Indeed, the association of NCSE with catatonic presentations has been suggested by prior literature.

36,37 It has also been argued that, in comparison to classic psychiatric literature, modern research on catatonia has focused more on motor rather than verbal signs of catatonia, including echolalia and verbigeration.

38 Our study suggests that there is a need for increased awareness of both verbal and nonverbal signs of catatonia, and that excited catatonia might be more frequently missed than retarded catatonia, given that agitation and grimacing are more frequently associated with excited catatonia.

15Interestingly, there were no significant group differences in variables like mean number of symptoms or distribution of number of symptoms, suggesting that it is the patterning of specific symptoms and not the overall number of symptoms that predicts under-diagnosis. There were no differences in rates of suspected delirium or NMS between groups, which suggests that these might not be factors driving the under-diagnosis. Of note, a high proportion of abnormal EEG findings were found in our sample, as have been reported in patients with catatonia regardless of an underlying medical or psychiatric etiology.

39 Our findings support prior literature showing that an abnormal EEG does not preclude the diagnosis of catatonia.

We also found limited evidence for demographic differences between groups. There was no difference between diagnosed and under-diagnosed groups in gender or past history of psychiatric diagnosis. Although age and race were initially significant in the univariate analyses, follow-up analyses (not shown) revealed that this was due to confounds with psychiatric consultations. Specifically, younger patients and African American patients were more likely to receive a psychiatric consultation. Similarly, these follow-up analyses revealed that neurology team evaluation and EEG tests were less common when a psychiatry consultation was requested, and all but two of the emergency department cases were seen by psychiatry consultants. Thus, when all of the factors were considered in the multiple regression simultaneously, only psychiatric consultation and the three clinical signs had significant, independent effects on under-diagnosis.

Finally, we note that there were some clinically relevant differences between groups in treatment received and clinical outcomes. First, a similar proportion of diagnosed and under-diagnosed cases received treatment with lorazepam during the episode, likely because lorazepam is widely used in our hospital for agitation management. However, under-diagnosis was related to lower daily doses of lorazepam received and lower rate of standing lorazepam treatment. Lorazepam is an effective treatment for catatonia, but high doses of lorazepam for several days or longer might be needed to treat catatonia effectively.

5,28,40 Thus, our study suggests that under-diagnosed cases received suboptimal treatment.

Moreover, even in diagnosed cases, the lorazepam treatment rates, standing lorazepam treatment rates, and average doses were relatively small, suggesting suboptimal treatment even when the syndrome is recognized. Suspected delirium comorbidity might explain suboptimal treatment among diagnosed cases, since in a secondary analysis of our data we found that treated case subjects with suspected comorbid delirium received significantly fewer total lorazepam doses than those without delirium only in the diagnosed group (N=17, mean=0.7, SD=0.7 mg/day versus N=12, mean=2, SD=1.6 mg/day, p=0.006). This finding suggests that clinicians might be reluctant to give optimal lorazepam doses in patients with catatonia and delirium, and that more evidence is needed on how to manage catatonia in the presence of delirium.

Although the data suggest that under-diagnosed catatonia case subjects have increased mortality during admission and increased length of stay, this was not statistically significant. Our study might have been underpowered to detect differences in mortality, given that less than 10% of the sample died during admission. Regarding length of stay, differences should be interpreted with more caution, since we did not compare differences in specific disposition among case subjects who did not die, such as a transfer to psychiatric hospital for catatonia management. However, we also suspect that our study might have been underpowered to detect differences in length of stay related to under-diagnosis of catatonia.

Overall, our findings suggest that under-diagnosis of catatonia might have played a role in increasing likelihood of poorer hospital outcomes. Future studies with larger samples could examine the effects of under-diagnosis on clinical outcomes.

Limitations

Results should be viewed in the context of several limitations. Because the study was based on retrospective chart review, we cannot be certain whether our under-diagnosed cases were truly catatonic. In fact, the BFCRS has not been validated as a tool to detect catatonia retrospectively.

While all of the diagnosed case subjects received a diagnosis of catatonia during admission, none of the subjects in the under-diagnosed group had a standardized catatonia exam, such as a BFCRS score, documented. However, since we could only find charts with documented symptoms, it is likely that there were more cases of catatonia with unrecognized and/or undocumented symptoms, and our sample represents an under-estimation of catatonia under-diagnosis. Better knowledge of catatonia by all physicians might help improve documentation of catatonic signs. We also acknowledge that our diagnosed and under-diagnosed groups might have differed on other factors that were not measured, such as degree of medical severity, which could confound our findings with regard to clinical outcomes. Finally, we note that the study was done in a single urban academic medical institution; thus, results may not generalize to hospitals in other settings.

Conclusions

A significant number of cases of catatonia in the general hospital might not be properly diagnosed and might be suboptimally treated. Consultation-liaison psychiatrists have a crucial role in the diagnosis and treatment of catatonia in the general hospital, and should implement liaison and educational strategies to increase the knowledge about catatonic signs, such as unexplained agitation, grimacing, or echolalia. Improving detection and treatment of catatonia could help improve clinical outcomes of patients with this reversible syndrome in the general hospital.