The septum pellucidum is a brain midline structure comprising two translucent parallel membranes, which fuse in an anterior to posterior direction in the first 3–6 months of life (

1). Abnormally, the failure of the fusion leads to the occurrence of cavum septum pellucidum (CSP). Many previous studies have suggested that, as a potential neurodevelopmental marker, CSP plays a role in the genesis of mental disorders, although its role remains unclear as suggested by the inconsistent correlations of this neuroanatomic finding with symptoms in schizophrenia (

2–

4). Shenton et al. have claimed that CSP is one of the most robust features of anatomical maldevelopment, related to the neuropathology of schizophrenia (

5). However, CSP is not specific to schizophrenia and has been reported to be associated with other mental disorders, such as bipolar disorder and depression (

6,

7).

The fusion of the septum pellucidum is considered to be associated with the rapid growth of its neighboring regions, such as the hippocampus, corpus callosum, and other midline structures (

8). Thus the occurrence of CSP is regarded as a reflection of abnormal development of structures bordering it (

9). Smaller bilateral amygdala and left posterior parahippocampal volume have been found in patients with large CSP (typically defined as a length from anterior to posterior larger than 6 mm) (

10).

To date, the prevalence of CSP in patients with mental disorders—particularly schizophrenia spectrum disorders and mood disorders—remains uncertain, as does the relative frequency of this abnormality in persons with mental disorders and psychiatrically healthy comparison subjects. Some studies have suggested that CSP is more common in mental disorders than in psychiatrically healthy comparison subjects, (

11) whereas others have indicated that the prevalence of this finding does not differ between such groups (

12). Recent meta-analyses have identified the prevalence of CSP in schizophrenia spectrum disorders and first-episode psychotic disorders, suggesting that CSP of any size (regardless of length) is not a risk factor for psychosis (

2,

13). However, these two meta-analyses found opposite findings for large CSP. In addition, the prevalence of CSP across subtypes of mental disorders, such as psychosis and mood disorders, also needs to be examined. A large-sample-based study that identified the prevalence of CSP in neuropsychiatric disorders suggested higher prevalence in psychosis and mood disorders compared with normal controls (

7). Nevertheless, relevant meta-analysis concerning the prevalence of CSP of any size and large CSP in subtypes of mental disorders is still lacking.

The discrepancies between former empirical studies may stem from different demographic features (e.g., mean age, gender, and sample size) and methodological factors (e.g., definition of large CSP, imaging technique, and detailed imaging parameters), as suggested by two meta-analyses conducted by Trzesniak et al. 2 and Liu et al (

13). In addition, prior meta-analyses included patients with schizophrenia or first-episode psychosis but did not include patients with mood disorders; thus, they failed to compare the prevalence of CSP in these two subtypes of mental disorders.

To verify former viewpoints, as well as to further extend knowledge on the current issue, we employed a quantitative meta-analysis to analyze individual studies that, using MRI, focused on the prevalence of CSP in individuals with mental disorders and psychiatrically healthy individuals.

Methods

The current meta-analysis was performed and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

Literature Search

We searched PubMed and Embase up to January 9, 2018, with the keywords mental disorders or mental diseases, and cavum septum pellucidum or cavum septi pellucidi. All studies that identified the prevalence of CSP among persons with mental disorders and among psychiatrically healthy individuals were evaluated under the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We further searched the listed references of included articles for possible related studies.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies included conformed to the following criteria: studies included only human subjects; articles were published in English; studies focused on mental disorders described in DSM-5; subjects included persons with mental disorders and psychiatrically healthy comparison subjects; mental disorders were clinically diagnosed (including patients with mood disorders who also had psychotic symptoms); studies used MRI to evaluate the prevalence of CSP.

Moreover, studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: focused on persons with genetic or ultra-high risk; reported as case report, review, or meta-analysis; included developmentally delayed persons; measured CSP in prenatal or early postnatal period, children, or teenagers.

Two reviewers (LXW and PL) assessed all articles according to the titles and abstracts and together determined whether the study met the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements pertaining to inclusion were solved immediately. The final decisions were made by consensus.

Quality Assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, which is used to appraise nonrandomized studies, was applied in this study. The whole current-topic specified version was made by consensus of all authors (see supplementary material 1). In brief, all articles contained in the present meta-analysis were assessed with three categories in the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: selection, comparability, and outcome. The maximum score of each individual study was 10, and studies graded with a score of 5 or more were regarded as moderate to high quality. Each study was evaluated by consensus of two reviewers (PL and FG). The meta-analysis was done with all included articles regardless of the scores on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Data extraction was performed subsequent to the quality assessment.

Data Extraction

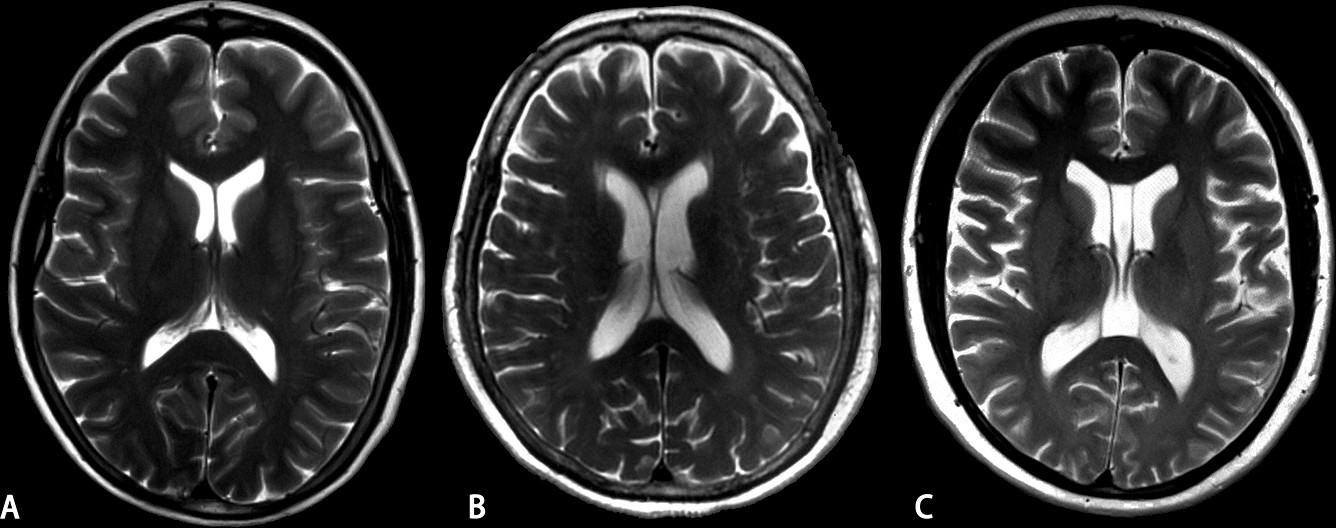

Two reviewers (LXW and HH) investigated full-text articles independently and extracted data in duplicate. The general information was recorded from texts and tables in individual studies. Multiple studies based on the same sample were further selected with a preference for the most comprehensive one. Additionally, corresponding 2×2 tables were constructed for each study, including the number of persons with mental disorders and psychiatrically healthy comparison that did or did not have CSP and large CSP. Specifically, we set the cutoff value of the length of CSP at 6 mm to define large CSP. An MRI image of CSP and large CSP is shown in

Figure 1. Any discrepancy pertaining to the data extraction was solved by consensus. If there were invalid data within a study, the corresponding author was contacted.

Meta-Analytical Calculation and Statistical Analysis

Meta-analysis was carried out using the Stata statistical software package (v.14.0; StataCorp). Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals of each study and pooled results were calculated. In the estimation of effect size, the DerSimonian-Laird random-effect model was used, in view of the previously reported high heterogeneity between studies. The chi-square and Higgins I2 of homogeneity were also calculated.

A predefined stratified analysis with schizophrenia spectrum and mood disorders was carried out on the basis of the potentially different etiologies of these disorders, which, in turn, could influence the prevalence of CSP. Furthermore, we conducted a subgroup analysis of first-episode and chronic mental disorders on the basis of the possible influence of illness duration. We also set the qualitative or quantitative ways to define the presence of CSP as one possible source of heterogeneity and performed a subgroup analysis.

Multiple-covariance meta-regression was performed to detect the effect of methodology-related distinctions. We set the imaging parameters (slice thickness and between-slice gap), quality of the study (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores), year of publication, and demographic characteristics (the mean age of participants) as potentially influential covariance. In addition to a modification of the variance of the estimated coefficients suggested by Knapp and Hartung, (

14) the default restricted maximum likelihood estimation method was implemented.

After the extraction of relevant data throughout full texts, no information about the between-slice gap was provided in articles by Borgwardt et al. (

15) and Fukuzako and Kodama (

16) and, and we could not contact the corresponding authors.

A sensitivity analysis was performed to validate whether the synthesized results were reliable. Moreover, estimation of publication bias was carried out with Egger’s regression test (

17).

A two-tailed p value <0.05 was recognized to be statistically significant.

Results

Literature Search

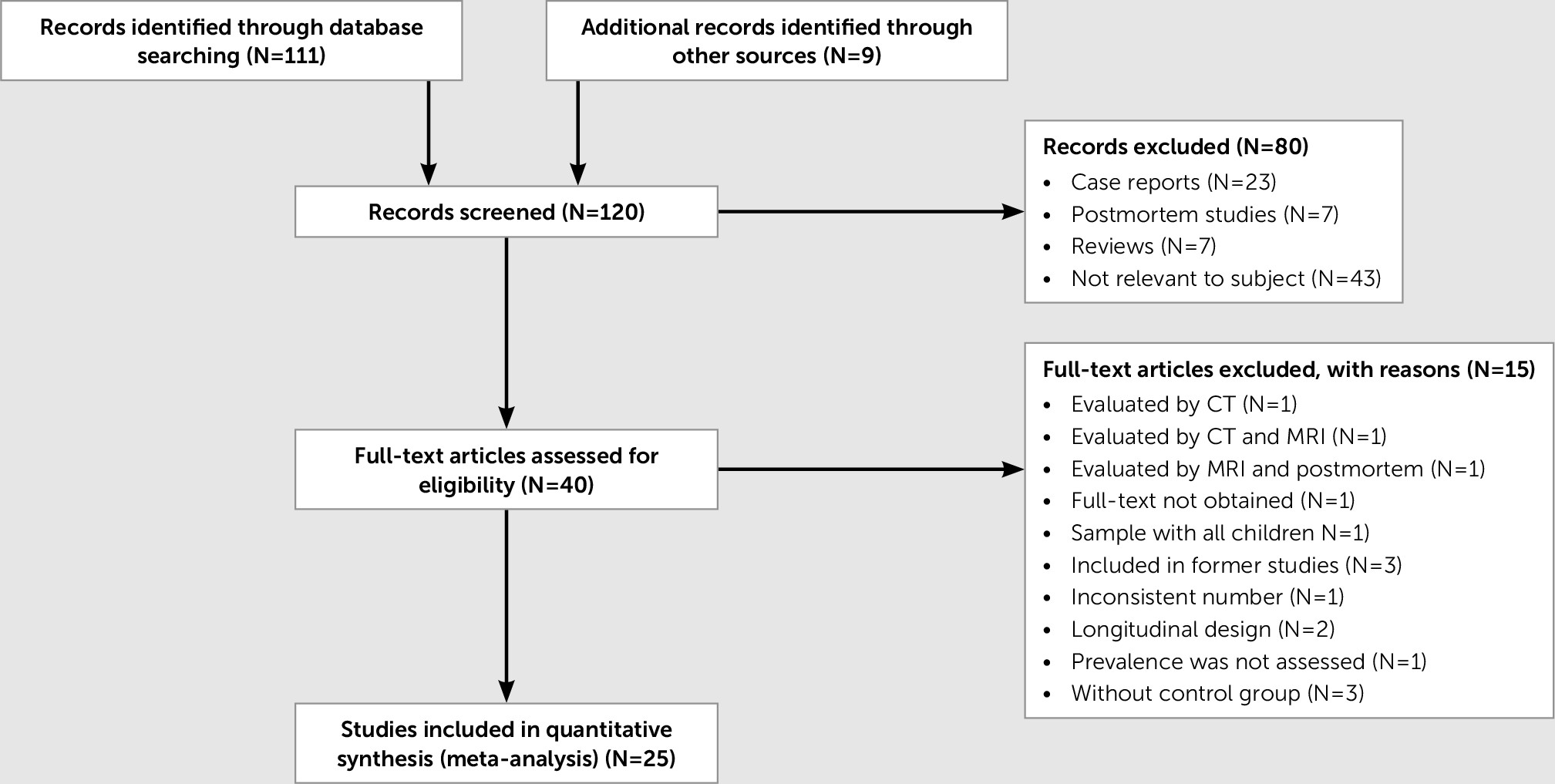

A total of 120 cross-sectional studies were screened by titles and abstracts, yielding 40 eligible articles examined by full-text according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (

Figure 2). Twenty-five articles were obtained for analysis, including 2,392 persons with mental disorders and 1,445 psychiatrically healthy individuals (

Table 1). Detailed reasons for included and excluded articles are available upon request. Among the included articles, 24 out of 25 evaluated CSP regardless of its size, and 12 out of 25 evaluated the prevalence of large CSP.

Quality Assessment

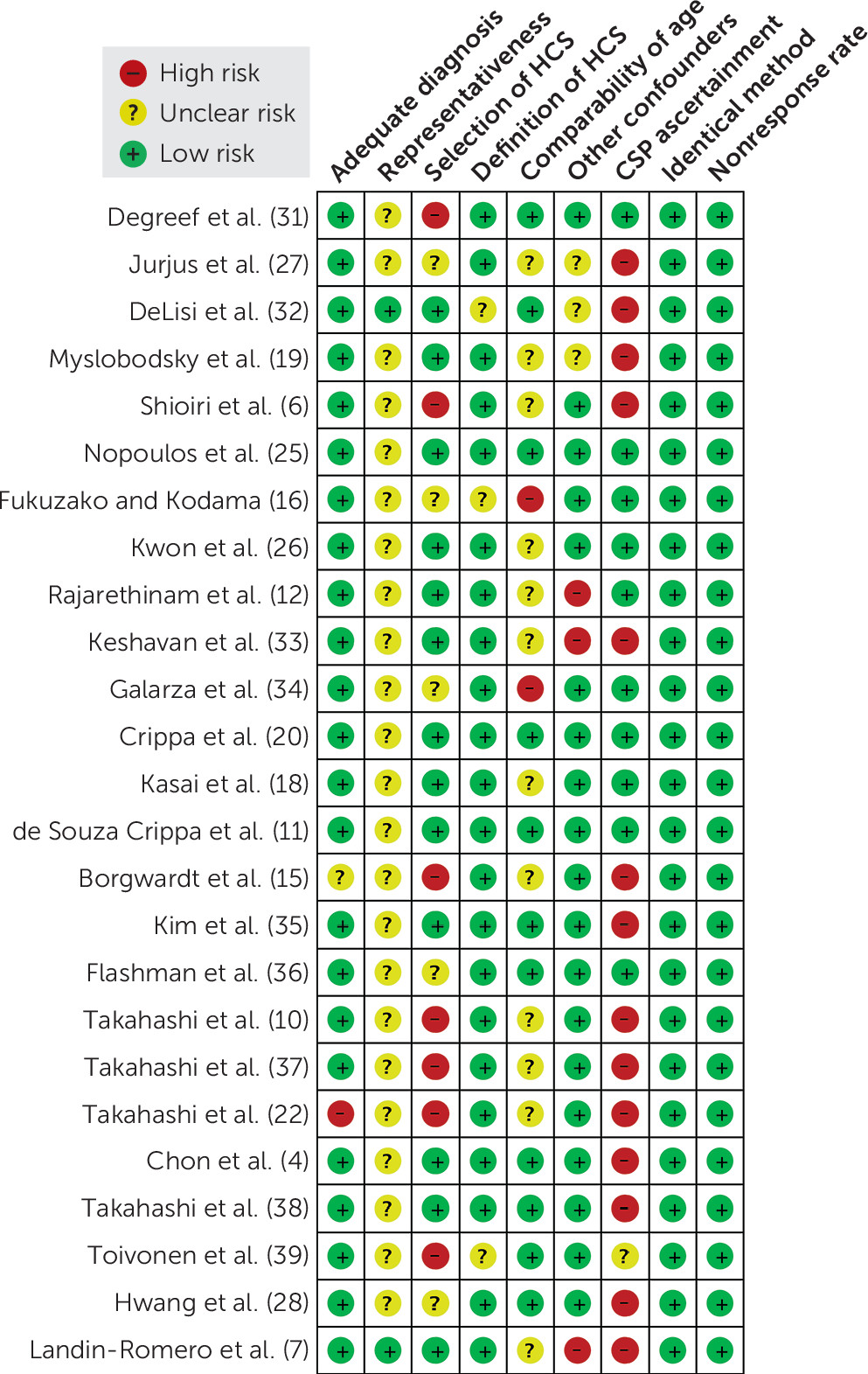

According to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, each included study was assessed, and the outcomes are shown in

Figure 3. In the realm of subjects’ selection, we found that the representativeness of patients was doubtful among included studies; namely, most of them showed no information about consecutive enrollment. Furthermore, the selection of controls and CSP ascertainment domains displayed relatively large inconsistency across included studies.

Prevalence of CSP and Large CSP

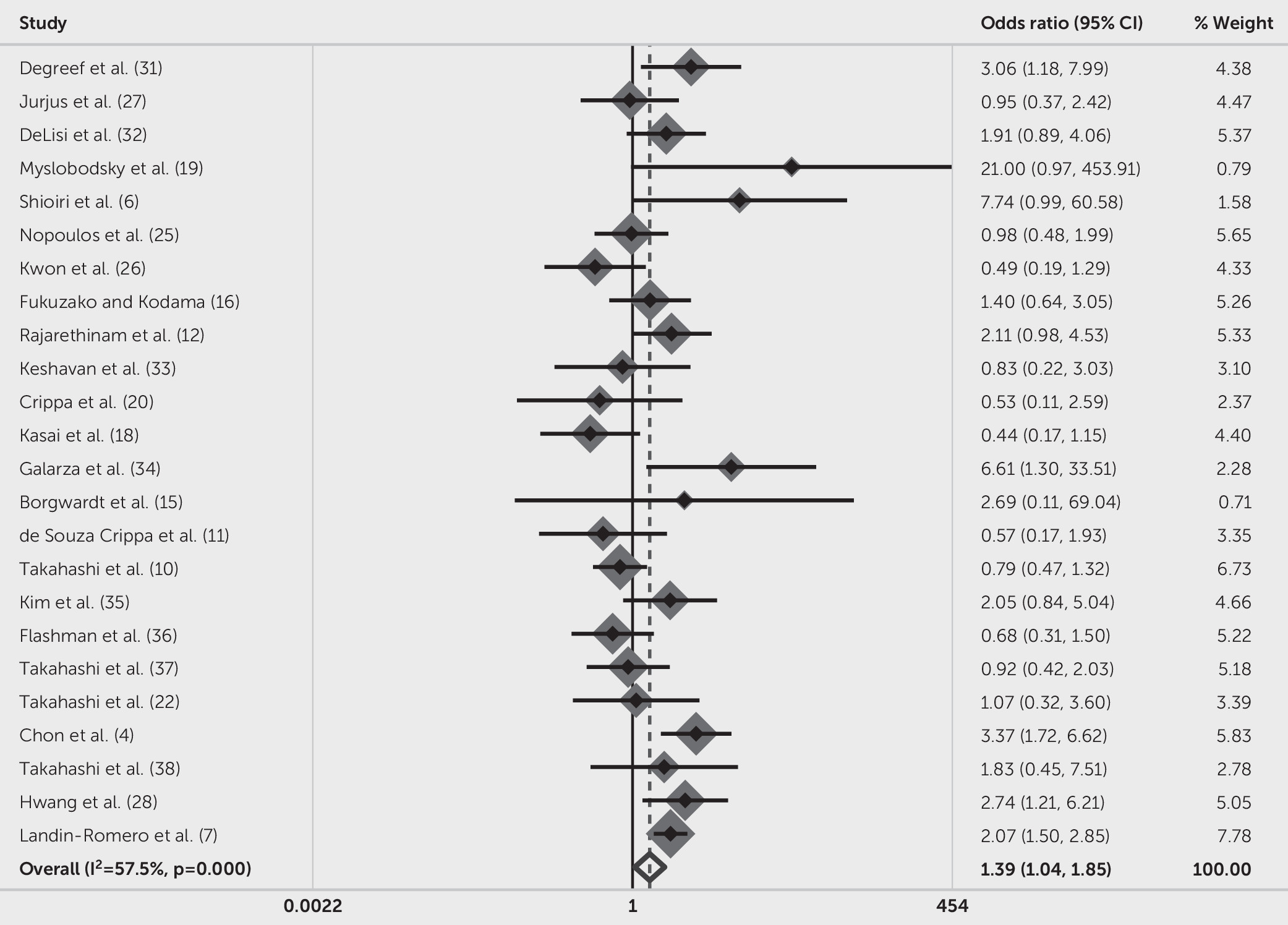

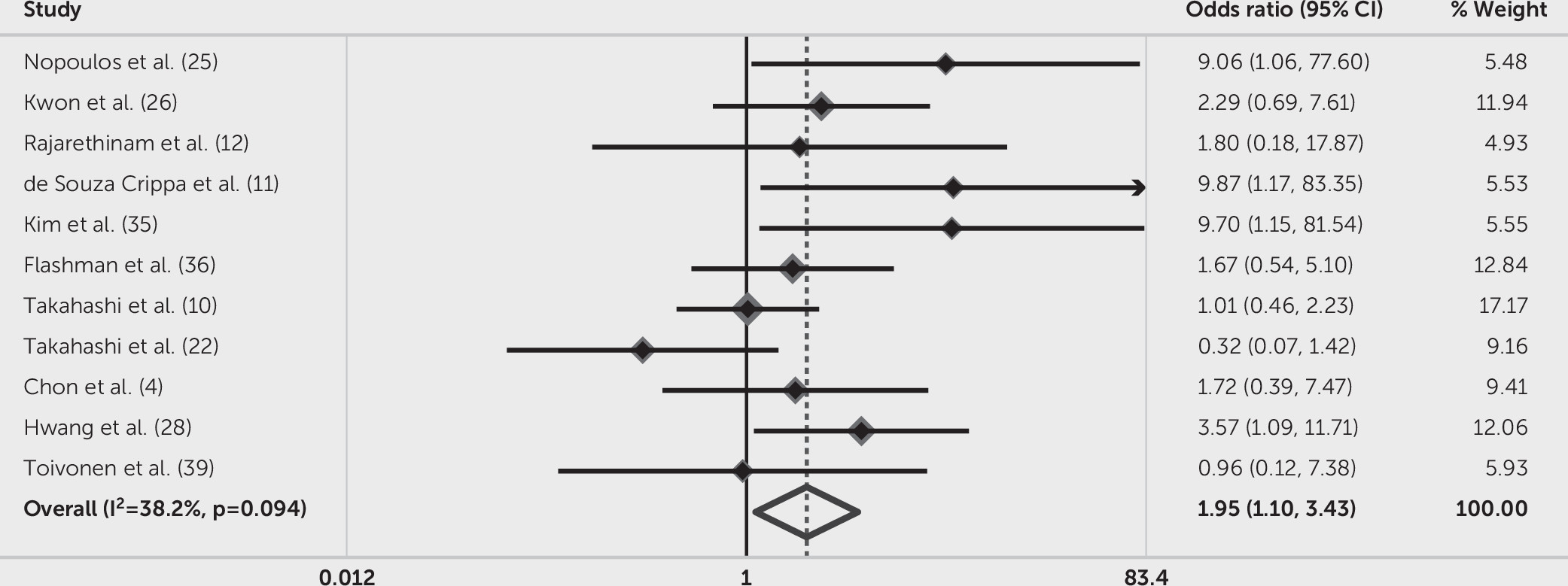

As to studies focused on the prevalence of CSP of any size, a forest plot of OR and 95% confidence intervals of each study and pooling results are presented in

Figure 4. Among the included articles, 11 out of 24 reported increased prevalence of CSP in mental disorders. The OR of studies varied from 0.44 (95% CI=0.17–1.15) (

18) to 21.00 (95% CI=0.97–453.91) (

19). The forest plot showed that the prevalence of CSP was significantly higher in patients with mental disorders compared with psychiatrically healthy individuals (OR=1.39, 95% CI=1.04–1.85, p=0.024). It should be noted that the variance in OR attribution to heterogeneity across all included studies was significant (I

2=57.5%, Q=54.08, p≤0.001).

With regard to large CSP (≥6 mm in length), six out of 12 studies found that the presence of this type of CSP was more common in persons with mental disorders than in psychiatrically healthy comparison subjects; other studies did not find significantly increased prevalence of CSP between these groups. We excluded the study by Crippa et al. (

20), because its results included two zeros in the fourfold table, which means any measure of effect summarized as a ratio was undefined and had to be discarded (

20,

21). The smallest OR was 0.32 (95% CI=0.07–1.42), (

22) and the largest was 9.87 (95% CI=1.17–83.35), (

11) which are presented in

Figure 5. Synthetic results showed that individuals with mental disorders had 1.95 times greater risk of CSP than psychiatrically healthy comparison subjects (OR=1.95, 95% CI=1.10–3.43, p=0.021). Different from the significant heterogeneity of CSP of any size, the heterogeneity across large CSP was lower (I

2=38.2%, Q=16.18, p=0.094).

Sources of Heterogeneity by Meta-Regression

Estimation of the source of heterogeneity by predefined confounding factors (slice thickness, slice gap, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores, and year of publication) revealed no statistically significant association (slice thickness: Coef.=0.45, p=0.118; slice gap: Coef.=−0.27, p=0.315; Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores: Coef=−0.03, p=0.865; year of publication: Coef.=0.05, p=0.254). However, regression with the mean age of included subjects as a covariance showed significant correlation (mean age: Coef.=0.06, p=0.049).

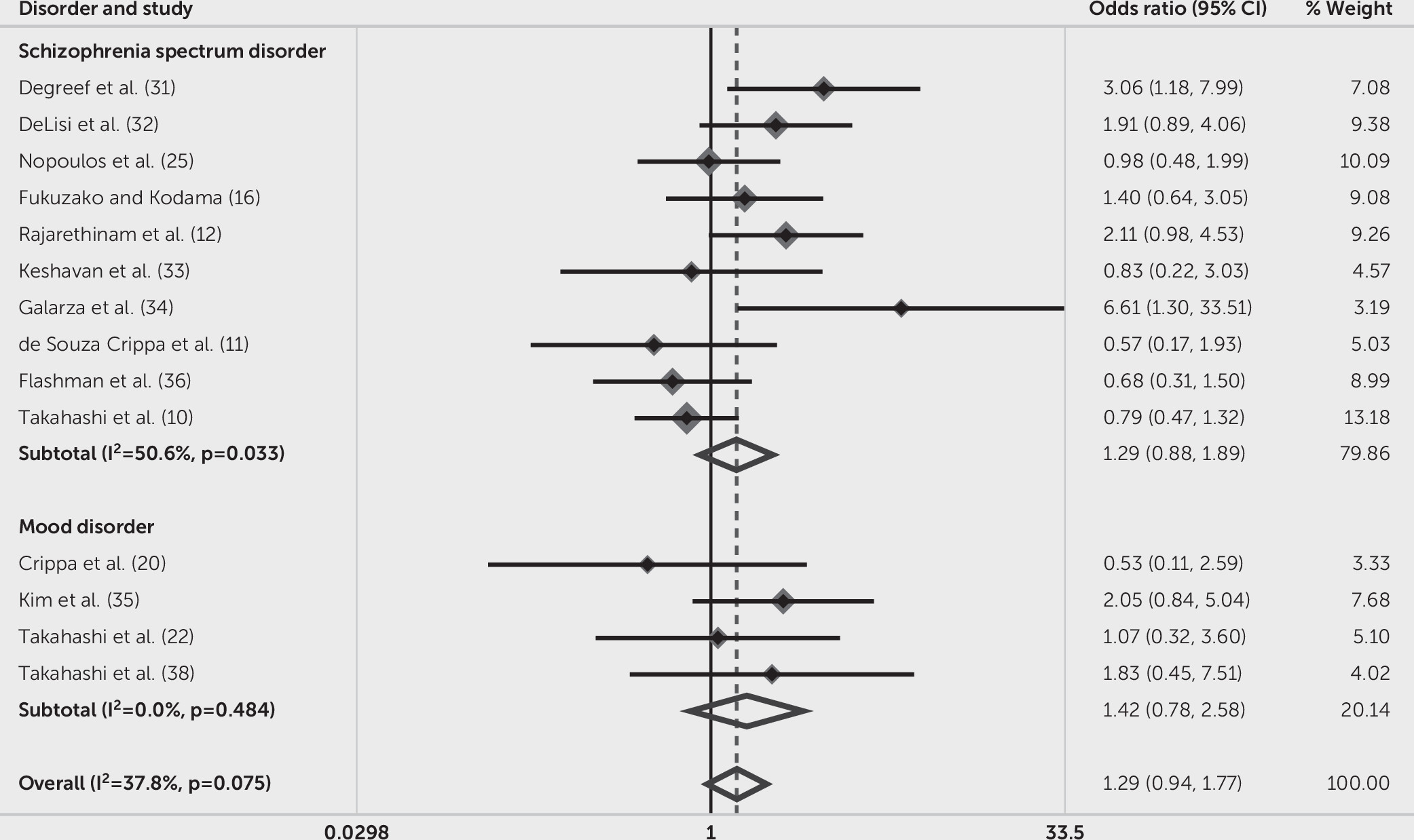

Subgroup Analysis

We evaluated the prevalence of CSP in schizophrenia spectrum disorders and mood disorders. Because mixed-sample studies contained more than one type of mental disorders, which might give rise to improper comparisons, we finally selected nine studies with only schizophrenia spectrum disorders and four studies with only mood disorders. The subgroup analysis showed that the heterogeneity decreased (schizophrenia spectrum disorders: I

2=50.60%, Q=18.20, p=0.03; mood disorders: I

2=0.00%, Q=2.45, p=0.48), with subtotal OR of schizophrenia spectrum disorders demonstrating nonsignificant but numeric difference from mood disorders (schizophrenia spectrum disorders: OR=1.29, 95% CI=0.88–1.89, p=0.20; mood disorders: OR=1.42, 95% CI=0.78–2.58, p=0.25). The overall pooled OR was 1.29 (95% CI=0.94–1.77, p=0.11; I

2=37.8%, Q=20.89, p=0.08) (

Figure 6). Subgroup analysis of studies with first-episode (three articles) or chronic (five articles) mental disorders, as well as studies using qualitative (five articles) or quantitative (17 articles) methods to define the presence of CSP, showed no significant results.

Publication Bias and Sensitivity Analysis

The Egger test did not reveal significant asymmetry of funnel plot in the current meta-analysis (CSP of any size: t=1.53, p=0.14; large CSP: t=1.55, p=0.16). The sensitivity analysis found that no individual study significantly influenced the stability of the pooled results.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that CSP of any size and large CSP were more common in mental disorders than in psychiatrically healthy comparison subjects. Compared with CSP of any size, the higher OR of large CSP revealed that patients with mental disorders were more susceptible to large CSP. Additionally, subgroup analysis found no significant difference between the prevalence of CSP in schizophrenia spectrum and mood disorders, suggesting similar neurodevelopmental etiology of those two subtypes of mental disorders. With regard to the noteworthy heterogeneity, meta-regression failed to show significant correlations between imaging parameters and heterogeneity, whereas the mean age of included subjects showed significant association with the heterogeneity, indicating that demographic characteristics might be responsible for the inconsistency of the original studies.

The findings regarding CSP of any size from our study were consistent with a former study, which found higher prevalence of CSP in schizophrenia and other mental disorders (

7). Together with our findings, the lack of diagnostic specificity of CSP suggests that this finding in these disorders may share a common neurodevelopmental etiology. A former meta-analysis found similar prevalence of CSP of any size in schizophrenia spectrum disorders and normal controls and claimed that the clinical significance of CSP depended more on its size than on whether it was present or absent (

2). However, this meta-analysis found that the prevalence of CSP of any size was higher in patients with mental disorders. Our results suggest that the failure in the fuse of septum pellucidum is associated with either schizophrenia spectrum or mood disorders, regardless of the size of the CSP. Furthermore, a previous meta-analysis suggested that CSP of any size and large CSP might not be associated with first-episode psychosis (

13). When compared with the two former meta-analyses, the discrepancies between findings in the present study may have resulted from differences in the patient groups studied, with prior meta-analyses including individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and first-episode psychoses and our study including persons with a broad range of DSM-5 mental disorders (

2,

13). Moreover, it has been reported that CSP of any size can also present in healthy individuals (

23). This indicates the possibility of CSP occurrence in normal controls, although patients with mental disorders tend to show higher prevalence.

Large CSP

The cutoff value of the definition of large CSP is controversial, varying from 4 mm to 6 mm. On the basis of postmortem findings, several studies recognized 6 mm as the threshold for large CSP (

24). Therefore, we set the cutoff value as 6 mm in the current meta-analysis. The OR of large CSP in patients was higher than CSP of any size when compared with normal controls (OR=1.94 of large CSP versus OR=1.39 of CSP of any size). Our result of large CSP is in accordance with former studies (

2,

25). Since the presence of CSP is related to the development of the structures bordering it, our result suggests that the large CSP reflects more severe structural alterations of surrounding brain areas in mental disorders.

CSP in Subtypes of Mental Disorders

A recent, large sample-based study showed that the risk of CSP was higher in mood disorders than in schizophrenia spectrum disorders (

7). However, opposite findings have also been reported. For example, a study suggested that schizophrenia spectrum disorders showed higher prevalence of CSP than mood disorders when comparing the two with normal controls (

26). In the present study, there was no significant difference in the OR for CSP between schizophrenia spectrum disorders and mood disorders, suggesting that patients with schizophrenia spectrum and mood disorders showed similar prevalence of CSP. The difference between the present findings and those reported elsewhere may lie in the relatively stricter inclusion criteria of the present study, which excluded nine articles pertaining to schizophrenia spectrum disorders and four to mood disorders.

Methodological Variations

We observed significant inconsistency across included studies. Interestingly, when synthesizing studies of large CSP, the homogeneity outperformed studies of CSP of any size, indicating better consistent findings within large CSP studies. Methodological variations in verification and definition of CSP, imaging parameters, and subjects’ characteristics could contribute to between-study inconsistency.

Demographic characteristics.

The demographic characteristics of included studies should be taken into account. A gender-based difference, in which males manifested higher prevalence of CSP than females in mental disorders, has been reported, (

25,

27) suggesting that unreliable conclusions could be drawn by sex mismatch. Additionally, if an individual study did not enroll patients consecutively and enroll normal controls from the community, confusion could be introduced in the results’ reliability. In this study, the mean age of included subjects in original studies was statistically significant as a covariance in meta-regression, indicating that mean age served as one possible source of heterogeneity and should be taken into consideration in future studies.

Different definitions of CSP.

Previous studies implemented different methods and criteria to evaluate CSP in mental disorders, including qualitative and quantitative approaches. In contrast to the qualitative method, the quantitative method mainly counts the multiplication of the number of slices that CSP presents. This method reflects the actual anterior to posterior length of CSP and is increasingly adopted by relevant studies, keeping pace with the development of imaging technique. The quantitative method has been proved to be objective and may introduce less bias in inspection of results. In this study, we found that the number of individual studies that reported higher prevalence of CSP in patients decreased after the use of the quantitative method, similar to the findings of Trzesniak et al (

2).

Imaging parameters.

Currently, the widely used acquisition parameter is 1 mm as slice thickness, without slice intervals. In this meta-analysis, the slice thickness varied from 0.5 mm (

28) to 5 mm (

27) and the between-slice gaps ranged from 0 mm to 5 mm (

25,

27). Nevertheless, meta-regression did not find significant associations between imaging parameters and heterogeneity, thus indicating that the inconsistency between individual studies might not arise from different imaging parameters.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI).

TBI has been reported to be related to psychiatric disorders (

29). Previous studies suggested that TBI was associated with the appearance of CSP (

30). In the current meta-analysis, 10 out of 25 studies did not provide information about the history of TBI, which could also be a potential source of heterogeneity.

Limitations

There are some limitations of this study. First, the relatively small sample size within subgroup analysis might lead to statistically nonsignificant results, with four articles available on mood disorders. The limited number of articles on mood disorders might be underpowered for tests of effect size and heterogeneity. Furthermore, the relatively large confidence interval of this subgroup hinted at potential inconsistency. Second, the descriptions of confounding factors such as previously used medication and clinical characteristics of patients were not sufficiently provided in some articles. Third, the between-study heterogeneity might affect reliability of the conclusion. As in all meta-analyses, effect sizes depend on the quality of original articles in the study. Significant heterogeneity may arise from methodological variations of primary studies. However, multi-covariance meta-regression indicated that the mean age of enrolled subjects served as one possible source of heterogeneity. Lastly, the number of studies concerning each subtype of schizophrenia spectrum and mood disorder was insufficient for meta-analysis. Therefore, the comparison of schizophrenia spectrum and mood disorders may be limited since no diagnostic subgroups were directly analyzed.

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis found elevated prevalence of CSP of any size and large CSP in patients with mental disorders. Furthermore, there was no difference in the prevalence of CSP between patients with schizophrenia spectrum and mood disorders. Meta-regression suggested that imaging parameters were not related to the heterogeneity across individual studies, while a demographic characteristic, namely the mean age of enrolled subjects, was associated with the inconsistency. By synthesizing available studies, our study provides new evidence of the potential effect of the presence of CSP and the association between CSP and mental disorders. Future studies are needed to recruit large-sample-based patients with first-episode mental disorders, as well as demographically matched normal controls. Together with clearly reported clinical variables, longitudinal design, and functional MRI, it is hoped that future studies will further evaluate the prevalence of CSP and illuminate the clinical significance of this neurodevelopmental aberrance.