Evidence regarding the effectiveness of CBT in treating mFND is limited. A case study reported benefits of up to a year for a patient with a functional dystonia after 12 CBT sessions (

11). A small pilot study reported improvements after CBT and adjunctive physical therapy, compared with standard medical care (

12). A number of trials have shown improvements when CBT is used for patients with nonepileptic seizures and with mixed FND (

13–

16). There is evidence of its effectiveness in other somatic symptom disorders (

17–

24), although one RCT comparing CBT to care from a primary physician found no significant difference in outcome (

25).

This evidence lends support to an a priori assumption that CBT will improve mFND symptoms, although such treatment may pose challenges because patients may be resistant to psychological accounts of symptoms, and such resistance would affect its uptake and effectiveness. No RCTs have tested the effectiveness of CBT for mFND.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of patients with mFND who received a course of CBT at an outpatient neuropsychiatry clinic in South London and Maudsley (SLaM) National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust. Because the study was observational and based on clinical practice within a single mental health NHS trust, we included a comparison group. This group comprised patients treated with CBT by the same clinical team for neuropsychiatric and behavioral manifestations of other neurological conditions. We compared sociodemographic characteristics, treatment dropout, and clinical outcomes. We hoped to establish evidence that could inform a future RCT.

Methods

Design and Source of Clinical Data

This was a retrospective comparison of two cohorts: patients with mFND and patients with other neuropsychiatric conditions (ONP) treated in a SLaM neuropsychiatry outpatient clinic between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2016. Data were obtained from SLaM’s Biomedical Research Centre Clinical Records Interactive Search (CRIS) database. CRIS holds anonymized records for more than 250,000 individuals referred to SLaM services (

26). This online system contains all patient information, medication, diagnoses, correspondence, and clinical outcome scores. Records can be retrieved by using searches of the database’s structured fields, such as age, gender, and diagnosis, or of free-text clinical notes and correspondence.

Study Setting and Participants

The outpatient neuropsychiatry services at SLaM treat patients with psychological complications associated with neurological disorders and functional and dissociative disorders. Patients receiving a CBT referral are offered an assessment after which they may be recommended a formal CBT course. A common treatment course is 12–15 sessions, usually occurring weekly.

The core components of CBT for FND are psychoeducation, cognitive and behavioral techniques, and relapse prevention strategies. Therapists challenge cognitive distortions that affect motivation, attempting to build insight so that patients may learn to accept a psychological understanding of symptoms. Some patients may be encouraged to link past and present experiences with physical symptoms, but this is not always the case. Other techniques include mood and thought diaries and relaxation and graded-exposure techniques to reduce behavioral avoidances.

Patients with mFND in this study were aged ≥18 with a primary or secondary diagnosis of conversion disorder with motor symptom or deficit (ICD-10 code F44.4) or those without a formal F44.4 diagnosis who received treatment for functional motor or movement symptoms. In these cases, mFND symptom management and improvement formed a large part of the focus of CBT. Patients received diagnoses in differing medical and psychiatric contexts, but all diagnoses were robust and were confirmed by a senior neurologist or neuropsychiatrist.

Patients in the comparison group were included if they were aged ≥18 treated in the same CBT clinic for psychiatric and behavioral manifestations of other neurological or neuropsychiatric conditions, and had no evidence of mFND or nonepileptic seizure symptoms. Some had comorbid functional somatic symptoms, such as irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue, and fibromyalgia.

Patients in both groups were excluded if they had a CBT assessment but their treatment had not begun. We included patients if CBT had begun but the course was not complete.

Ethical Approval

The CRIS database received ethical approval from the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee as an anonymized data set for mental health research.

Outcome Measures

We extracted information on year of birth, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, employment, housing status, receipt of benefits, use of walking aids, having a caregiver or being a caregiver, physical comorbidity, lifetime experience of sexual or physical abuse, age at onset of any psychological symptom (any symptom, not exclusive to FND), CBT assessment date, and acceptance of psychological formulations before and after CBT. Acceptance of psychological formulations was assessed by using information from detailed case notes written by CBT therapists or case notes and referral letters from patients' consultant neuropsychiatrists.

CBT attendance was calculated as the number of sessions attended out of the number of sessions offered. Information on treatment dropout was recorded.

We created a 3-point scale to measure patient improvement: symptoms improved, remained the same, or got worse. Improvements of patients in the ONP group were based on the goal set by the patient and therapist at the start of therapy. Assessment of improvement was based on the view expressed by CBT therapists in their case notes or referral letter to the consultant neuropsychiatrist at the end of treatment. Neuropsychiatric symptom management and improvement was a goal common to both groups, but only in the FND group did we expect to observe motor function improvement.

We collected scores on the following instruments: Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation–Outcome Measure (CORE-OM), Health of the Nation–Acquired Brain Injury (HoNOS-ABI), and nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The CORE-OM is a 34-item self-report questionnaire measuring psychological distress. It has good criterion validity with other mood scales and has high internal consistency for secondary care (α=0.95) (

27). HoNOS-ABI assesses the neuropsychiatric factors linked to brain damage. The scale correlates with established outcome measures—for example, postinjury employment (

28)—and has good interrater reliability (

29). The PHQ-9 assesses depression severity and demonstrates good internal consistency, a test-retest reliability of 0.87, and criterion validity with the Beck Depression Inventory of 0.79 (

30). On each of these three instruments, lower scores indicate better outcomes.

Pre-CBT and post-CBT scores were classified as those taken nearest the CBT assessment date and the final CBT treatment or follow-up session. Scores were included if they were measured within 180 days of the date in question. A comparison of pre- and post-CBT scores assessed change over time and response to treatment.

Statistical Analysis

We used means, standard deviations, and frequency data to assess differences between the mFND and ONP groups. Chi-square analyses were used for frequency data, Mann-Whitney U calculations were used for nonnormally distributed score comparisons, and proportions were used to describe categorical data. An exact McNemar’s test was used to determine the change in the proportion of patients with mFND who accepted psychological formulations before and after CBT. A repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) assessed the change in CORE-OM scores and their associations with sociodemographic variables. We conducted a binary logistic regression analysis to assess associations between sociodemographic variables and symptom improvement in patients with mFND. Using a simultaneous selection model, we adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, employment, caregiver status, receipt of benefits, disability, acceptance of psychological formulations, and experience of abuse. The following software was employed: SPSS for Windows, version 21.0; Microsoft Excel, version 14.0.7015.1000; and GraphPad Prism, version 5.01.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Our search returned 941 patients, of whom 573 were patients with functional disorders with nonepileptic seizures but no evidence of motor symptoms. A further 21 did not meet other study criteria (e.g., age <18). A total of 102 individuals were excluded from the mFND group and 71 from the ONP group because they had not begun treatment. The most common reasons for not beginning CBT in the mFND group were referral to the Trust’s inpatient neuropsychiatry ward (36.3% versus 19.7% in the ONP group; χ2=5.5, 95% confidence interval [CI]=2.1–30.0, p<0.05), nonattendance at appointments (19.0% versus 26.8%; χ2=1.6, 95% CI=–4.2 to 21.0, p>0.05), and treatment refusal (13.7% versus 2.8%; χ2=5.9,95% CI=2.2–19.2, p<0.02).

A total of 98 mFND patients and 76 ONP patients began CBT, and they formed our study sample. In the ONP group, epilepsy was the most common disease (N=43, 46.2%), followed by Tourette’s syndrome (N=16, 17.4%), sleep disorders (N=7, 7.6%), multiple sclerosis (N=5, 5.4%), and other neurological diseases (N=22, 23.9%). The most common neuropsychiatric difficulties for which patients in the ONP group received treatment were depression (N=29, 22.7%), anxiety (N=25, 19.5%), low mood (N=20, 15.6%), sleep disorders (N=9, 7.0%), obsessional thoughts and compulsions (N=10, 7.8%), self-harm and suicidal ideation (N=10, 7.8%), panic disorders (N=7, 5.5%), low self-esteem (N=7, 5.5%), and anger management, agoraphobia, and personality changes (N=11, 8.6% total). Most patients had more than one complaint, and there was considerable overlap between symptoms. Data on sociodemographic characteristics, experience of abuse, and lifetime prevalence of fatigue, anxiety and depression in both groups are presented in

Table 1.

The most common mFND symptom was weakness (N=47, 26.9%), most frequently in the leg or entire body, followed by pain (N=46, 26.3%) and tremor, shakes, jerking, or dystonia (N=43, 24.6% total). All patients in the mFND group had at least one motor symptom: 83.7% (N=82) experienced two motor symptoms, 40.8% (N=40) experienced three, and 12.2% (N=12) experienced four. Of patients in the mFND group, 22.4% (N=22) had a history of nonepileptic seizures. Rates of comorbid physical health conditions and other comorbid functional symptoms in both groups are presented in

Table 1.

Openness to a Psychological Formulation

Of the 98 patients with mFND, prior to therapy commencement, 49 (49.0%) accepted a psychological formulation, 27 (27.6%) did not, and 13 (13.3%) were unsure. In 10 cases, no data were available or a psychological account was not applicable. After therapy, we assessed acceptance of a psychological formulation in 95 patients: 68 (71.6%) accepted a psychological account, 17 (17.9%) did not, and five (5.3%) were unsure. In eight cases (8.3%), this was not known. A significant increase was noted in the proportion of patients accepting a psychological account after CBT (McNemar’s test, p=0.004).

Treatment Attendance

The mean number of treatment sessions attended was 14.1 (SD=8.00; range, 1–46) for patients in the mFND group and 13.4 (SD=7.3; range, 1−40) for patients in the ONP group. Rates of attendance are presented in

Table 1.

In total, 28 patients in the mFND group ended treatment early, and in six cases the therapist discontinued the sessions early. Reasons for dropout or early cessation were as follows: five believed a physical cause explained their symptoms, three believed therapy was ineffective or worsened symptoms, three reported that the clinic was too far away, two reported that their symptoms improved, two had a physical health problem that impeded attendance, and four reported miscellaneous reasons. No information on dropout was available for 15 mFND patients. In the ONP group, 20 patients ended treatment early, and two patients’ therapists discontinued the sessions early. Three believed therapy was ineffective or harmful, and five reported miscellaneous reasons. No information on dropout was available for 14 ONP patients.

A comparison of patients in the mFND group who dropped out and those who completed therapy indicated no statistically significant differences in age, gender, marital status, race/ethnicity, employment, acceptance of psychological explanations, walking aid use, or treatment outcome scores. However, in the mFND group, the percentage who were victims of childhood sexual abuse was larger among those who dropped out than among those who completed therapy (36.7% versus 16.3%; χ2=3.9, 95% CI=–1.7 to 42.0, p=0.05).

Outcomes

To avoid bias in our analysis of symptom improvement, we included all 98 mFND and 76 ONP patients. This included patients for whom therapy was ongoing at the time of data collection, patients who did not complete the full course of therapy, and patients whose clinicians prematurely ceased sessions. Because all patients had completed an extensive course of treatment, an assessment of outcome was possible.

Table 2 presents data on improvement rates for patients in the mFND group. In total, 44 (49.4%) patients with mFND showed symptomatic improvement, compared with 40 ONP patients (58.0%) (a nonsignificant difference). Eight mFND patients (8.2%) got worse, compared with nine ONP patients (11.8%). No information on patients’ improvement was available for nine mFND patients (9.2%) and seven ONP patients (9.2%).

For patients in the mFND group, we compared sociodemographic characteristics of those whose symptoms improved and those whose symptoms stayed the same or got worse.

Table 2 presents data for adjusted and unadjusted comparisons. In the logistic regression model, the only significant predictor of improvement was acceptance of a psychological formulation before therapy. The model explained 63% (Nagelkerke R

2) of the variance in symptom improvement between those whose symptoms improved and those whose symptoms stayed the same and correctly classified 50% of cases.

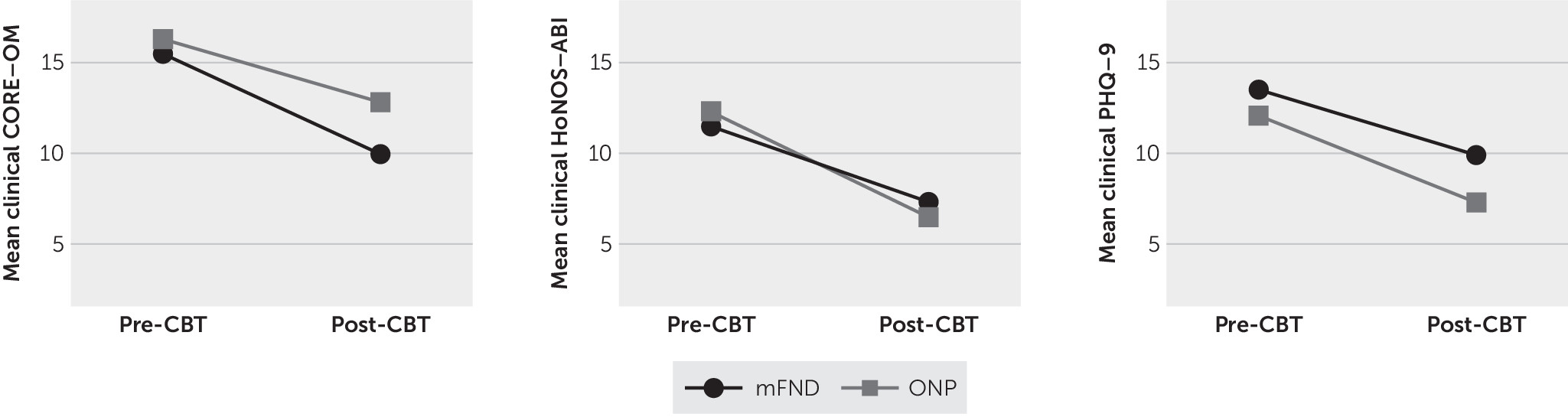

The results below are based on subsets of the 98 mFND patients and 76 ONP patients for whom pre- and post-CBT scores were available for the CORE-OM, HoNOS-ABI, and PHQ-9 (

Figure 1; see the figure footnote for the sample sizes). Among patients in the mFND group, the mean global CORE-OM score decreased from a mean of 15.5 (SD=6.2) (clinically moderate) pre-CBT to a mean of 10.0 (SD=6.6) (clinically low) post-CBT (t=3.9, df=23, 95% CI=2.6–8.3, two-tailed p=0.001). Scores of patients in the ONP group also decreased significantly, from 16.3 (SD=6.8) (clinically moderate) to 12.8 (SD=6.6) (clinically mild) (t=2.9, df=23, 95% CI=1.06–5.9, two-tailed p=0.007).

We conducted a repeated-measures (pre- versus post-CBT) ANOVA on CORE-OM scores, with patient group (mFND versus ONP) as a fixed factor. The main effect was statistically significant (F1=24.3, p=0.001, partial η2=0.35). The Bonferroni-corrected interaction between mFND and ONP groups and the change over time (pre- versus post-CBT) was not significant (F1,46=1.13, p=0.30, partial η2=0.02).

In the mFND group, the mean HoNOS-ABI score dropped significantly, from 11.5 (SD=6.0) to 7.3 (SD=5.0) (Z=–3.1, p=0.002). In the ONP group, the mean HoNOS-ABI score also decreased significantly, from 12.3 (SD=7.0) to 6.5 (SD=4.0) (Z=–3.0, p=0.003). A two-way repeated measures ANOVA found a significant main effect (F1=22.6, p=0.001, partial η2=0.39); however, no significant interaction was found between the groups’ changes in pre- and post-CBT scores (F1,35=0.58, p=0.45, partial η2=0.02).

In the mFND group, a statistically significant decrease in PHQ-9 scores was observed post-CBT, from 13.5 (SD=7.0) to 9.9 (SD=6.0) (t=2.6, df=15, 95% CI=0.6–6.5, two-tailed p=0.02). A repeated-measures two-way ANOVA found a significant main effect (F1=10.1, p=0.01, partial η2=0.29); however, the interaction between the mFND and ONP groups and the change in pre- and post-CBT scores on the PHQ-9 was not statistically significant (F1,24=0.22, p=0.64, partial η2=0.01).

CORE-OM scores were significantly correlated with HoNOS-ABI scores (r=0.68, p=0.01) but not with PHQ-9 scores (r=0.78, p=0.06). HoNOS-ABI and PHQ-9 scores were not significantly correlated (r=0.26, p=0.47).

For all three measures, we compared sociodemographic characteristics of patients with available scores and those with no available scores. No significant differences were noted.

Discussion

In this small, retrospective chart review, results suggested that outpatient CBT treatment for mFND had positive effects on motor symptoms, distress, depression, general health, and social functioning. Among the patients in the mFND group, half saw improvements in their physical symptoms, and only a small proportion saw their symptoms worsen (8.2%).

We evaluated whether specific characteristics contributed to symptom improvement. Previous positive prognostic factors in FND include being married (

31,

32) and younger age at onset (

33,

34). One study found that females were more likely than males to recover (

3), but this has not been reported elsewhere (

31,

35–

37). We found no effect of gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, sexual abuse, or age at symptom onset on symptom improvement. However, the long delay we observed between symptom onset and the offer of treatment is a concern for NHS services.

Our regression analysis revealed a strong predictive variable in symptom improvement: acceptance of psychological accounts of symptoms prior to receipt of CBT, which corroborates previous findings (

32,

38,

39). By “psychological,” we mean an information-processing account that invokes attentional processes, attribution errors, and behavioral avoidance and that acknowledges the temporal relationships between symptoms and “stress,” mood, anxiety, or dissociation. When patients do not accept a psychological formulation, CBT therapists may invest more time in explaining this perspective, patients may be less likely to use therapeutic tools outside the clinic, and building a therapeutic alliance may be more challenging.

Symptom severity might independently explain symptom improvement and patients’ acceptance of a psychological formulation prior to CBT. In our analysis, we used patients’ use of a walking aid as a proxy of symptom severity, and pre-CBT psychological acceptance remained a significant predictor of improvement. However, it should be noted that use of walking aids is a broad measure and is relevant to most, but not all, of the mFND patients in this study.

Although pre-CBT acceptance of psychological explanations predicted patient improvement, three patients with mFND did not accept this explanation after receipt of CBT but nonetheless experienced symptomatic improvements. Saifee et al. (

39) argued that psychological attributions could be used as a criterion to select patients for CBT. Our findings suggest that improvement may be possible regardless of attribution, albeit in a small proportion of patients. Although symptom reattribution is an important part of CBT, other techniques, such as mindfulness, establishing a sleep routine, and helping solve obstacles to recovery, may be as effective.

That only half the mFND group experienced physical symptom improvements might appear low, but previous literature indicates that FND prognosis is poor. A systematic review found that 39% of patients with mFND had the same or worse symptoms at follow-up, and only 20% had complete remission (

40). An RCT testing CBT for patients with medically unexplained symptoms (N=79) reported that 51% of patients maintained improvement at 12-month follow-up, a finding comparable to our own (

17).

The goal of CBT in functional disorders may not always be the immediate reduction of physical symptoms but rather improvement in cognitions and behaviors associated with symptoms. Patients’ goals are commonly discussed and agreed upon at the start of therapy. Had our symptom score derived purely from the goals set at the start of therapy, it is possible that a higher proportion of patients would have been classed as improved.

The psychometric measures showed significant improvements in both groups. The HoNOS-ABI is clinician rated, and it is possible that clinicians give more favorable scores at the end of treatment. Many NHS services, however, implement quality control measures, such as independent assessors. The CORE-OM and PHQ-9 are self-report scales and thus are not subject to clinician bias. Only a minority of patients in both groups had a complete set of pre- and posttreatment scores, which may represent a biased sample. To account for this, we compared sociodemographic differences on all three measures between patients for whom pre- and post-CBT scores were available and patients whose pre- or post-CBT scores or both were missing. No differences were found. We conducted a further analysis, assessing pre- and post-CBT scores according to the treating clinician and found no differences.

There are several weaknesses inherent in this observational study. The observed improvement in measures may be explained by a placebo effect; a regression-to-the-mean phenomenon; nonspecific effects of psychotherapy, such as the therapeutic relationship; or other therapeutic inputs, such as medication, physiotherapy, or occupational therapy. The focus of CBT sessions may have been different for mFND and ONP patients, which may have accounted for a proportion of the observed differences. However, our findings suggest that CBT in patients with functional disorders is at least as effective as CBT for patients with other neuropsychiatric conditions and significant psychological comorbidities. In fact, the results for patients in our comparison group make a unique contribution to the literature on the range of disorders responsive to a tailored CBT intervention.

The numbers in our study were relatively small, and our use of a medical register means that clerical errors could not be corrected. We could not blind the data collector. Because of the lack of availability of outcome scores, we included scores available within 180 days of the assessment or final CBT session—a long window of time in which psychological symptoms could have fluctuated. Interpretations and extrapolations from our regression analysis are also limited because of the small sample and the large number of observations. This study represented patients willing to accept a referral. The national referral status of the clinic may restrict attendance of patients living further from the clinic, a specific concern in a group with chronic motor deficits. We do not know whether the observed improvements were sustained over a longer period.

Finally, unlike a traditional RCT, in our study clinicians were not following a treatment manual. However, our naturalistic results do not reflect the imposition of strict selection criteria, which can limit generalizability. Instead this study offers useful information on the practicalities of delivering CBT in the NHS. Our results also provide information on CBT refusal, findings potentially pertinent to future service planning.