Despite a recent acceleration of research (

1), functional neurological disorder (FND) is still poorly understood by health professionals as well as the pubic (

2). The fact that the need for identification of a precipitating stressor has been dropped from DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for FND (

3) does not mean that psychosocial factors, including negative life experiences of trauma, negative affect, and relationship insecurity, do not play important roles (

4–

6). Indeed, evidence for a causal relationship between FND and negative life experiences, such as childhood neglect or trauma, is not only based on correlational or association studies but also emerges from prospective longitudinal research (

6–

10).

In view of this evidence—and the likely relevance of these factors, if present, for therapeutic formulation or patient stratification in research—a standardized measurement approach could be of great importance clinically and in research studies. Unfortunately, existing measures of trauma tend to be intrusive and time-consuming. For example, the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (

11), a 25-item measure, and the Life Events and Difficulties Schedule (

12), a semistructured interview that can take 2–4 hours to complete, have been used for individuals with FND (

13,

14). Both measures are so detailed and intrusive that they may cause distress to patients or research participants. In addition, to our knowledge, no combined measures of trauma, negative affect, and relationship insecurity exist that have been validated in this patient population. Moreover, existing measures fail to differentiate between developmental phases during the respondent’s life span, although developmental vulnerabilities vary in different life phases (

15,

16).

To address this gap, we developed a novel short questionnaire: the Lifespan Negative Experiences Scale (LiNES) (

17). LiNES asks adults to retrospectively rate their experiences of interpersonal trauma, negative affect, and relationship insecurity during three life phases: childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (

17). In a nonclinical population, LiNES scores at each developmental stage were found to reliably predict reports of both physical symptoms and difficulties with emotional processing in adulthood (

17). A key strength of LiNES is that it has been designed to be minimally invasive in terms of the number and nature of the questions it asks. For example, the Childhood Abuse and Trauma Scale (CATS) (

18), an established trauma measure, consists of 38 items and asks questions about experiences of abuse in more detail than necessary or appropriate for a screening or stratification tool. Moreover, CATS focuses only on traumatic experiences in childhood, and like most established questionnaires, it measures trauma by focusing on objective events (e.g., number of experiences or perpetrators), rather than on their subjective effects, although there is little evidence that information about objective events is relevant to the occurrence of posttraumatic symptoms (

19).

LiNES has been designed for use in clinical settings, but it was validated in a nonclinical sample (

17). The study reported here was intended to examine whether LiNES could be useful for the identification of predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors in patient populations. Consequently, we compared data from patients with FND with data from healthy persons in a control group. Furthermore, we explored the construct validity of the LiNES by studying correlations with previously validated measures of related domains, such as childhood abuse and trauma, positive and negative affect, physical symptoms, and the quality of interpersonal relationships.

Methods

Participants

Patient participants were recruited via e-mail through online forums for persons with nonepileptic attack disorder (NEAD) or FND. As detailed below, the final patient sample included individuals with FND only, with FND and NEAD, and with NEAD only. Healthy control subjects were recruited via e-mail through a volunteer database (for current students at the University of Sheffield and alumni and staff). Data for participants in the control group were used previously in the original LiNES validation (

17). All participants were offered the chance to enter a prize draw for a £20 voucher. To increase the number and diversity of participants in the control group, individuals were asked to share the survey link with at least one person who was not affiliated with the University of Sheffield. Ethical approval was granted by the University of Sheffield Psychology Department Ethics Committee.

Procedure

This study was conducted using the Qualtrics online survey software (Qualtrics, 2015).

Measures

Participants’ demographic characteristics.

Participants provided information on their date of birth, gender, country of birth, and race/ethnicity. Participants were also prompted to report any relevant diagnoses (mental health conditions, neurodevelopmental differences, seizures, or medically unexplained symptoms) and who their primary childhood caregivers were. Respondents used the SES Ladder (

20) to rate their socioeconomic status at two life stages, once for the family in which they grew up and once for their current circumstances. Respondents in the NEAD-FND group (referred to hereafter as the FND sample) were asked about employment status, diagnosis, symptoms, and treatment history.

LiNES.

LiNES consists of 13 items grouped into three subscales: interpersonal trauma (four items), negative affect (five items), and relationship insecurity (four items). Each item is rated on a 7-point scale (0, not at all, to 6, a lot) (for further details, see the online supplement). Respondents must rate all 13 items three times, thinking about their childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Scores are calculated for each subscale at each developmental stage by calculating an average across the items within that subscale at each stage. For this study, subscale scores were calculated without replacing any missing data as long as no more than one item per subscale was missing. Scores were not calculated if more than one item per subscale was missing.

Construct validation measures.

Three previously validated measures were chosen to support the convergent validity of each of the three LiNES subscales in the FND sample.

Early life trauma was measured by the 38-item CATS (

18), which has good psychometric properties (overall Cronbach’s α=0.90) (

18,

21). Each item is rated on a scale from 0, never, to 4, always. The original publication describes three subscales: sexual abuse, punishment, and neglect–negative home atmosphere. An additional emotional abuse subscale was created and validated by using items not included in the original three subscales (

21). A total CATS score was also calculated (mean of the responses to the 38 questions).

Affect during the previous week was measured by using the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (

22), which has good psychometric properties (negative affect and positive affect subscales: Cronbach’s α=0.85 and 0.89, respectively).

The 30-item Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ) was used to measure previous attachment and experiences in relationships (

23). Similar to LiNES, it does not ask about any particular relationship (e.g., with parents or romantic partners). The RSQ yields two attachment dimensions (anxiety and avoidance), with good psychometric properties (anxiety: Cronbach’s α=0.83; avoidance: Cronbach’s α=0.77) (

24).

Physical symptom measure.

Current physical symptom reporting was measured by using the 20-item Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ) (

25). Higher SDQ scores are associated with a greater likelihood of symptoms not being attributable to pathophysiological or structural abnormalities (

26).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed by using SPSS, version 25. The alpha level was set at a p value of 0.05. Tests used were two-tailed. The risk of false-negative findings was reduced by the Benjamini-Holm procedure. Histogram plots of LiNES, PANAS, CATS, RSQ, and SDQ scores indicated that the majority of scores were not normally distributed. Hence, nonparametric analyses were conducted. Internal reliability of LiNES subscales was examined by calculating Cronbach’s alpha.

To explore changes in interpersonal trauma, negative affect, and relationship insecurity across the three developmental stages in the FND and control groups, each subscale score was compared across all developmental stages. Spearman’s correlation coefficient scores between childhood and adolescence, childhood and adulthood, and adolescence and adulthood were highly significant for FND patients and control subjects and for each subscale (p<0.001) (for further details, see Table S5 in the online supplement). However, t tests (Wilcoxon signed-ranks test) and effect sizes suggested that some subscale scores differed significantly at different developmental stages. Where these were significant, effect sizes were calculated.

Whether LiNES subscales could predict the likelihood that participants had FND was tested by stepwise (forward) binomial logistic regression based on average lifetime scores for all three LiNES subscales: interpersonal trauma, negative affect, and relationship insecurity. Included in the model were age, childhood socioeconomic status, and gender as independent variables. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to calculate discrimination accuracy of the model.

To explore whether different presentations of functional disorders in our final patient sample are associated with different predisposing factors (

27), we compared findings among individuals with FND only, with FND and NEAD, and with NEAD only by using t tests (Mann-Whitney).

Results

Participants

Demographic data for the study participants are presented in

Table 1. For the FND sample, of 104 people who opened the survey link, 71 (62 females) completed the sections pertaining to demographic information and all items of the LiNES (68% completion rate), suggesting that most found the measure acceptable. For the healthy control sample, of 373 people who opened the survey link, 271 (194 females) completed demographic information and all items of the LiNES (73% completion rate); 37% of these were excluded, because they reported having a diagnosis of at least one disorder. Therefore, the healthy control sample included in this study consisted of 170 individuals (109 females).

Participants were matched for race-ethnicity and country of origin. However, the healthy control sample had a lower median age, compared with the FND sample, and included a larger proportion of male participants. In addition, patients with FND reported a significantly lower socioeconomic status, both currently and during childhood, compared with control subjects. Most participants in the FND group (59%) reported their employment status as on leave or out of work due to illness. When asked about educational status, 36% of the FND sample had obtained vocational qualifications. No employment or educational data were available for the healthy control group.

Clinical Symptoms in the FND Group

Of the 71 patient participants, most (N=36, 50.7%) self-reported a diagnosis of FND only, eight (11.3%) reported a diagnosis of NEAD only, and 27 (38%) reported both diagnoses. The 71 patient participants reported high levels of comorbid conditions. The six most commonly self-reported diagnoses in this group were anxiety (N=41, 57.7%), depression (N=40, 56.3%), chronic pain/chronic fatigue/irritable bowel syndrome (N=37, 52.1%), posttraumatic stress disorder (N=11, 15.5%), epilepsy (N=8, 11.3%), and other mental health problems (N=9, 12.7%). Almost all patient participants (N=65, 91.5%) were taking some form of medication (median=3 mediations; range=0–18), and 47 (66.2%) stated that they had received some form of psychological treatment. In the patient sample, seizures were the most commonly reported disabling symptom (N=24, 33.8%), followed by paralysis (N=10, 14.1%), tremor (N=5, 7%), and weakness (N=3, 4.2%).

Self-Reported Measures Among FND Patients and Control Subjects

FND participants reported higher levels of negative affect and lower levels of positive affect, compared with control subjects, as well as higher levels of trauma and avoidant and anxious relationship styles. Furthermore, FND participants scored significantly higher on the SDQ, compared with subjects (for further details, see Table S1 in the online supplement).

LiNES

Internal consistency.

Internal consistency was acceptable to very good in the FND group (Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.78 to 0.96). In the control group, internal consistency ranged from 0.52 to 0.86. Notably, with the exception of the interpersonal trauma subscale in the control group, internal reliability was acceptable for all three subscales. The internal consistency of the trauma subscale in the control group may have been low because of low or absent levels of trauma in many respondents. (Cronbach’s alpha values are presented in Table S2 in the online supplement).

LiNES scores for FND patients and control subjects.

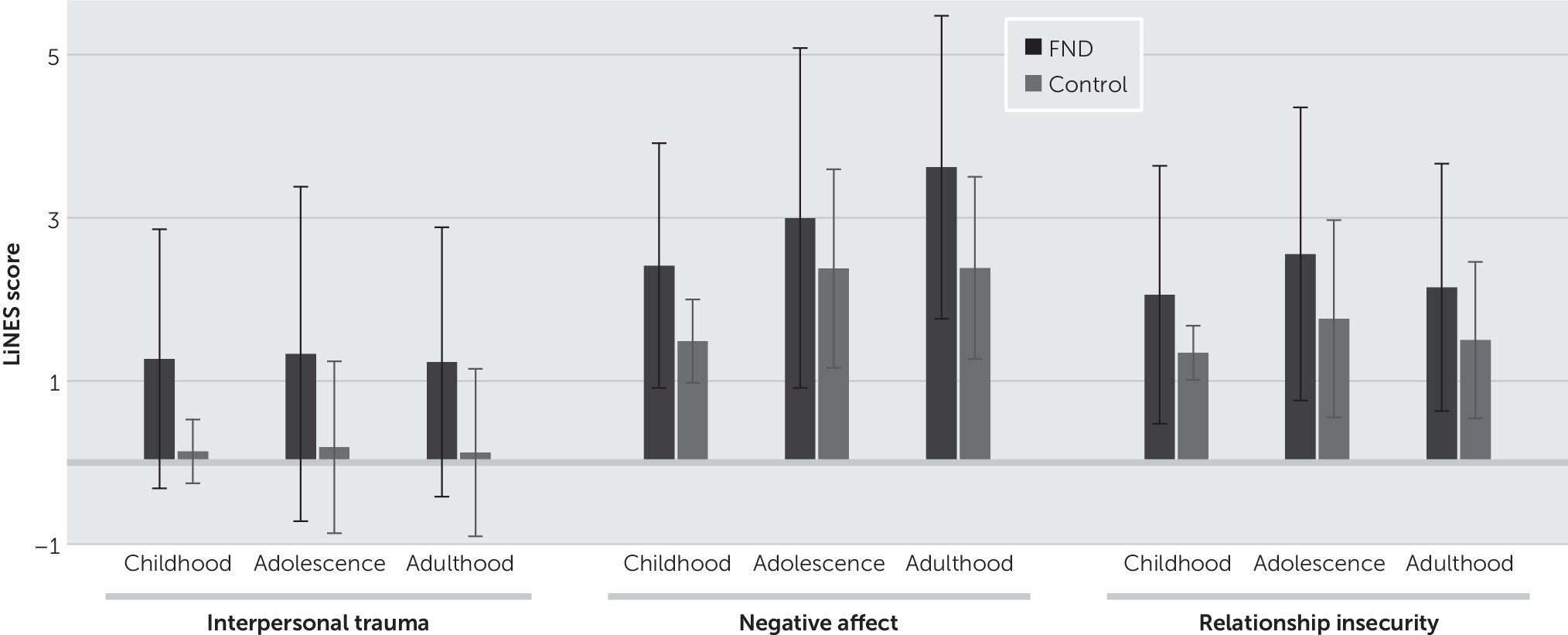

FND participants reported higher levels of interpersonal trauma, negative affect, and relationship insecurity at all three stages of development, compared with control subjects (

Figure 1) (see also Table S3 in the

online supplement). Notably, although the between-group differences in trauma scores (FND versus control) were significant, with higher scores for FND participants than for control subjects, the within-group differences in trauma scores between each developmental stage were not significant (Friedman test) in either the FND or control group (FND group, χ

2=1.68, df=2, p=0.432; control group, χ

2=0.084, df=2, p=0.656). In contrast, for both negative affect and relationship insecurity, significant within-group differences were noted (Friedman test) in both the FND and control groups in scores across the three developmental periods (negative affect: FND group, χ

2=30.37, df=2, p<0.001; control group, χ

2=100.13, df=2, p<0.001; relationship insecurity: FND group, χ

2=16.30, df=2, p<0.001; control group, χ

2=35.38, df=2, p<0.001).

Of the 71 patients in the FND sample, 36 reported FND only (four males, 31 females, and one other; mean age=44.89 years [SD=11.43]), 35 reported either FND including NEAD or NEAD only (four males and 31 females; mean age=42.6 years [SD=12.010]). For those who reported NEAD (either with FND or NEAD only), levels of interpersonal trauma during childhood and adolescence were significantly higher, compared with patients with FND only; the difference during adulthood approached significance (p=0.051). Differences in other LiNES subscales between these patient subgroups were not significant after correcting for multiple comparisons (see Table S4 in the online supplement).

LiNES: consistency of experiences across the life span.

Changes in experiences of trauma, negative affect, and relationship insecurity across the three developmental stages in the FND and control groups are presented in Tables S5A and 5B in the

online supplement. For interpersonal trauma, the Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests did not identify any significant differences between the scores for three developmental stages for either the FND group or the control group. Of interest, among both FND patients and control subjects, we found an increase in negative affect and relationship insecurity during the adolescent period. It is noteworthy that negative affect continued to increase into adulthood only among FND participants. For relationship insecurity, after showing an increase from childhood to adolescence among both patients with FND and control subjects, a significant reduction in this domain at the transition into adulthood was observed only among the control subjects (

Figure 1).

Construct validity.

The LiNES subscale scores in the FND sample were expected to correlate with existing, validated measures of interpersonal trauma (CATS), negative affect (PANAS), and relationship insecurity (RSQ). Significant Spearman’s correlation coefficients were identified for each of the LiNES subscales, CATS total and subscales, PANAS subscales, and the RSQ anxious style subscale but not the RSQ avoidance style subscale (see Table S6 in the online supplement).

Prediction of FND diagnosis based on lifetime LiNES interpersonal trauma.

Binomial logistic regression based on average lifetime scores of all three LiNES subscales was run; included in the model were age, childhood SES status, and gender as independent variables. The assumption of linearity of the continuous variables in our model (age, socioeconomic status, and LiNES subscale scores) with respect to the logit of the dependent variable as assessed via the Box-Tidwell procedure was met. A Bonferroni correction was applied using all 12 terms in the model, resulting in statistical significance being accepted at p<0.004. On the basis of this assessment, all continuous independent variables were found to be linearly related to the logit of the dependent variable. In addition, five standardized residuals with values of –2.69, 2.79, 3.20, 3.08, and 3.82 were found, which were kept in the analysis

Explanatory variables that were retained in the final model were LiNES interpersonal trauma, LiNES relationship insecurity, age, and gender (χ

2=129.63, df=4, p<0.0001) (

Table 2). Thus higher levels of trauma and relationship insecurity were associated with a greater likelihood of having FND. Compared with females, males had lower odds (odds ratio=0.23) of having FND, and greater age was associated with an increased likelihood of having FND. Socioeconomic status and LiNES negative affect did not contribute to the model. This final model explained 59.5% (Nagelkerke R

2) of the variance in FND and correctly classified 82.9% of cases. Sensitivity was 60.0%, specificity was 92.4%, positive predictive value was 73.4%, and negative predictive value was 84.9%. The area under the ROC curve was 0.912 (95% confidence interval=0.876–0.948), an outstanding level of discrimination (

28).

Discussion

Using the new LiNES, we assessed self-reported experiences of interpersonal trauma, negative affect, and relationship insecurity at three developmental stages—childhood, adolescence, and adulthood—among patients with FND. We found that the LiNES is an internally consistent and reliable questionnaire with good construct validity. The interpersonal trauma, negative affect, and relationship insecurity LiNES subscales correlated highly with more detailed older measures of trauma, affect, and attachment. Lifetime scores on the LiNES interpersonal trauma and relationship insecurity subscales, but not on the negative affect subscale, reliably predicted FND status.

By using LiNES, we found that individuals with FND had higher levels of interpersonal trauma, negative affect, and relationship insecurity at all three developmental stages, compared with healthy control subjects. Cronbach’s alpha exhibited good internal consistency of the LiNES among patients with FND. Moreover, the LiNES correlated highly with previously validated measures of the three constructs, although with just 13 items completed once for each developmental stage, it is much shorter and likely to be more acceptable than the more established measures. Our findings of higher levels of interpersonal trauma are consistent with those of other studies, which have revealed high levels of trauma in the early life and adulthood of patients with FND (

6,

29).

The strength of LiNES is its ability to measure negative experiences longitudinally. This revealed important differences in changes in such experiences among individuals with FND, compared with control subjects. We found that negative affect and relationship insecurity increased significantly during adolescence for both FND patients and control subjects. Indeed, the life changes that occur during adolescence are often associated with an increase in the experience of emotional and interpersonal turmoil (

30). However, only among patients with FND did the negative affect increase further during adulthood.

The high levels of negative affect reported by FND participants in this study are consistent with the idea that functional symptoms are physical manifestations resulting from emotional distress (

29,

31). Negative affect is thought to be a risk factor and has been found to be associated with functional symptoms (

32). Likewise, an insecure attachment style, which was also high in the FND group, has been found to be associated with functional symptoms (

33,

34) and could influence a person’s help-seeking behaviors. For example, having an insecure, anxious attachment style could make an individual more likely to experience distress and to report common physical symptoms (

35). In support of this, we found a positive association between the SDQ score and the LiNES relationship insecurity subscale score among FND patients.

The temporal changes across the life span in negative affect and relationship insecurity among the FND and control groups contrasted with steadily elevated levels of interpersonal trauma across the life span. Likewise, we found little lifetime variation in the low levels of trauma among control subjects. Much work has been done on the association between trauma history and FND (

6). Consistent with a recent review (

6), our study found that patients with FND had higher levels of trauma, compared with control subjects, during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Moreover, our analyses demonstrated that the LiNES lifetime interpersonal trauma and relationship insecurity scores could be used to reliability predict FND status, providing an initial indication of the potential clinical validity of the LiNES and further evidence of an etiological link, at a group level, between trauma and FND. Consistent with the idea that differences in traumatic experiences may shape functional symptoms (

27), the results of our analysis comparing FND-only patients with patients reporting both NEAD and FND indicated that those in the NEAD subgroup reported significantly higher levels of interpersonal trauma during childhood and adolescence, with higher levels in adulthood approaching significance.

It is noteworthy that our findings need to be viewed in light of this study’s limitations. First, patients in the FND group were recruited through Internet forums for patients with this diagnostic label or one of NEAD. They were asked to self-certify that they were diagnosed as having one of these disorders, and the diagnoses were not medically confirmed. Therefore, we cannot be certain that all would have met the DSM-5 criteria for FND. It is possible that some patients may have received a diagnosis of FND or NEAD from a nonspecialist without appropriate assessment. However, it is unlikely that a substantial number of participants wrongly self-reported that they had FND or NEAD. We note that the demographic and psychopathological profile indicated by patients’ responses to previously validated self-report measures matches the profile described in previous studies of FND. Furthermore, the diagnostic uncertainty related to our recruitment procedure has to be weighed against the fact that we may have captured data from a group of patients who were less acutely unwell, compared with those whom we might have recruited from a specialist clinic. On the other hand, it is possible that patients frequenting FND Internet forums and willing to take part in research studies represent a particular subset of FND patients with higher rates of psychopathology or trauma history than other patients with FND.

Next, the participant groups were not matched with regard to gender, age, and socioeconomic status. This is an issue because there are gender differences in the types of trauma men and women are exposed to or are likely to report (

36), and trauma is more prevalent among deprived populations (

37). However, we tried to address this by taking into account age, socioeconomic status, and gender in our logistic regression analysis. Furthermore, LiNES is based on retrospective recall. The additional validated measures used in this study provided some reassurance about the reliability of retrospective reports. However, it is possible that the perception of childhood trauma was related to recall bias associated with adulthood trauma (that is, instead of childhood trauma setting individuals up to also experience trauma in adolescence and adulthood). Finally, we acknowledge that our results are correlational, and more work is needed to examine the causal relationships between trauma, negative affect, and relationship insecurity and FND.