Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is clinically and radiologically diagnosed and characterized by subcortical vasogenic cerebral edema, with characteristic neuroimaging appearances. Its commonest known precipitants are drug toxicity (

1), hypertension, sepsis (

2), preeclampsia, and autoimmune disease. In a review of the literature of the past 20 years, Gao et al. (

3) highlighted unanswered questions about the underlying pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, and prognosis of PRES. The importance of clinical suspicion has been emphasized (

4); however, presenting symptom descriptions have been confined to summarized neurological categories, such as seizures, headaches, “confusion,” and “altered mental function” (

5–

7). Studies of the psychiatric sequelae of PRES and its mental health comorbidity are, to our knowledge, absent from the literature.

Following the description of new neuropsychiatric syndromes, such as anti-

N-methyl-

d-aspartate receptor encephalitis (

8), interest in potentially reversible “organic” etiologies of psychiatric presentations has expanded markedly (

9,

10). Research on psychiatric outcomes of acute neurological disorders is well established, but recent work on encephalitides is noteworthy, reporting high rates of anger, anxiety, mood swings, and low mood (

11). For example, a large population-based retrospective cohort study revealed elevated risk ratios for bipolar affective disorder (risk ratio=6.34) as well as for psychotic (risk ratio=3.48), depressive (risk ratio=1.88), and anxiety (risk ratio=1.46) disorders postencephalitis (

12). Comorbid psychiatric disorders are associated with worse quality of life in a range of neurological disorders, including multiple sclerosis (

13), epilepsy (

14), and migraine (

15).

Based on clinical experience, we hypothesized that a proportion of patients diagnosed with PRES would develop psychiatric symptoms during and after the acute illness. We aimed to identify all cases of PRES radiologically diagnosed in a large teaching hospital over a 10-year period to audit psychiatric precipitants, symptoms, and sequelae, alongside clinical and etiological correlates.

Results

Case Detection

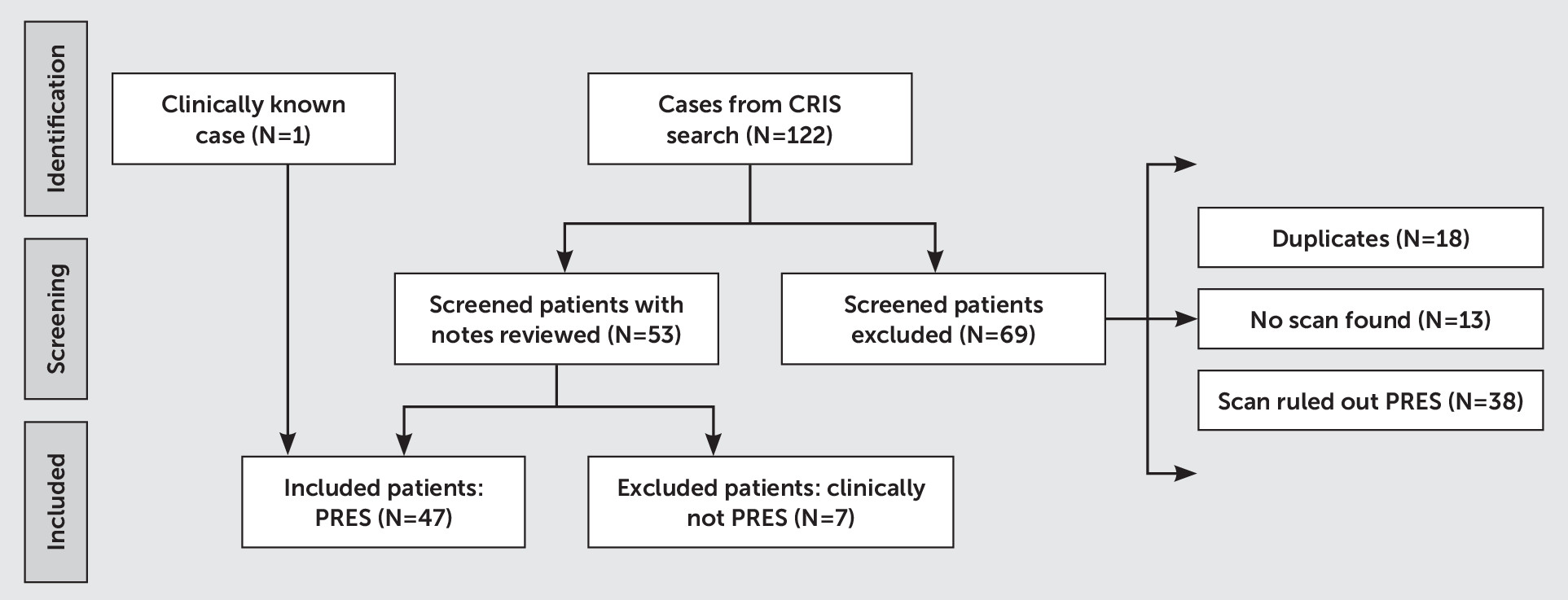

Of an initial 122 results, 69 patients were excluded at initial screening (duplicates, N=18; no scan recorded, N=13; and PRES ruled out radiologically, N=38;

Figure 1). On the basis of 53 clinical notes reviewed, we excluded seven cases in which the ultimate clinical or radiological impression was not PRES. Forty-seven case subjects were included in the final study sample, including one whose diagnosis was reported by the neurology team.

Demographic Characteristics

Of the 47 included case subjects, 33 (70%) were female, with a median age of 39 years at presentation (range, 5–74 years).

Neuroimaging

Radiological reports revealed that abnormalities were bilateral in 44 (94%) case subjects; of these, 25 (57%) were asymmetrical. Gray matter involvement was mentioned in 23 (49%) reports, and abnormalities were more pronounced in posterior regions compared with anterior regions in 40 patients (85%). Involved brain regions were occipital (N=40; 85%), parietal (N=37; 79%), frontal (N=20; 43%), temporal (N=17; 36%), cerebellar (N=12; 26%), basal ganglia (N=7; 15%), and brainstem (N=4; 9%).

Presenting Symptoms

The most common presenting symptoms were seizures (N=38; 81%), reduced consciousness (N=29; 62%), headache (N=12; 26%), visual abnormalities (N=12; 26%), and nausea and vomiting (N=11; 23%). Focal neurological signs were documented for 10 (21%) patients, with confusion and agitation present in seven (15%) cases each.

Etiology

Acute hypertension was identified in 34 (72%) patients. When blood pressure at the time of presenting symptoms was electronically documented, the mean systolic pressure was 185 mmHg (SD=24; range, 140–234 mmHg; N=22), and the mean diastolic pressure was 109 mmHg (SD=19; range, 71–140 mmHg; N=17). Possible drug toxicity was identified in 27 (57%) patients, including for tacrolimus (N=8; 30%), cyclosporine (N=6; 22%), and a range of other agents, which included cancer chemotherapeutic agents (N=4; 15%), anti-inflammatory drugs (N=4; 15%), and antibiotics (N=2; 7%). Infection or sepsis was present in 22 (47%) patients; of these cases, 10 (46%) involved chest sepsis, and each of three (14%) involved both HIV opportunistic infections and skin infections, while other cases involved bacterial infections, including clostridium difficile diarrhea (N=2).

Medical Comorbidities

The commonest medical comorbidities were hematological (N=14; 30%), including aplastic anemia (N=3), acute leukemias (N=3), myelodysplastic syndrome (N=2), and sickle cell anemia (N=2). The second most common comorbidities were autoimmune disorders (N=13; 28%), including systemic lupus erythematosus (N=5; 38%), sarcoidosis (N=2; 15%), and autoimmune hepatitis (N=2; 15%). Chronic liver disease affected 11 (23%) patients, while eight (17%) patients had chronic kidney disease, with seven (88%) requiring renal replacement therapy. Seven patients were diagnosed with malignancy (15%), and four (9%) had a history of seizures. Three PRES cases (6%) occurred during a pregnancy or postpartum period.

Management

The most frequently prescribed treatments were antiepileptic medications (N=13; 27%), antihypertensive medications (N=13; 27%), or a combination of both (N=8; 17%). Five patients (11%) received treatment for potential CNS infection, and in 11% of these, no specific treatment for PRES was provided beyond management of comorbid disorders or withdrawal of the suspected toxic agent.

Prognosis

Seven patients (15%) died during the index hospital admission, one patient was discharged to palliative care, and five patients died after the index hospital admission, resulting in a mortality rate of 28% during the follow-up period. Age of death ranged from 5 to 74 years old, with a median age of 41 years.

Psychiatric Contact

Eighteen (38%) case subjects had some form of contact with local psychiatric services. This subgroup of patients had a higher median age (44 years old versus 39 years old), a higher proportion of females (83% versus 70%), and a higher mortality rate (33% versus 28%) compared with the total sample. Psychiatric services contact comprised pre-PRES consultation (N=7; 15% of all cases), liaison psychiatry referrals during the index admission (21%), and post-PRES consultation (21%). The median duration of psychiatric services consultation from PRES onset until hospital discharge was 677 days (range, 7–3,123 days).

Premorbid Conditions

Reasons for psychiatric treatment before PRES diagnosis were assessments of low mood and suicidality (29%), regular consultation from addictions services (29%), mental capacity assessments due to dialysis refusal (29%), and routine assessment pretransplant surgery (14%).

Psychiatric PRES Symptoms

Mental state abnormalities were documented in 12 PRES case records (26%). These abnormalities were speech disturbance (67%), confusion (58%), agitation (58%), hallucinations (33%), disinhibition (25%), low mood (25%), delusions (17%), bad or vivid dreams (17%), and religious preoccupation, self-harm, and anxiety (8%). Of the 10 patients who were referred to liaison psychiatry, only one was evaluated for symptoms directly related to PRES, and three were evaluated for symptoms identified once PRES had been treated. The remaining referrals were for medication overdoses that precipitated hospital admission (20%), cognitive or mental capacity assessment (20%), or substance-use nurse review (20%). The one patient who was referred to psychiatric services during PRES onset and treatment was evaluated for grandiose and persecutory delusions and auditory hallucinations. The three patients who were evaluated for post-PRES symptoms were referred for agitated depression and suicidality, low mood and vivid dreams, and advice regarding antipsychotic medication.

Psychiatric Symptoms Post-PRES Hospital Admission

Of the 10 patients who received psychiatric services post-PRES hospital admission, four were referred for low mood, along with acute delusions, suicidality, erratic behavior, or reduced oral intake. In addition, four patients were referred regarding their capacity to refuse treatment or self-discharge; of these, comorbid addictions were present in three. Two patients were referred for acute confusion, along with persecutory delusions or rapid cognitive decline.

Discussion

In this study, we found that psychiatric symptoms were not reported in all cases of PRES, although confusion and agitation were common. However, psychiatric symptoms often occurred before, during, or following PRES onset, which is consistent with evidence of psychiatric comorbidities in neurological disorders, including epilepsy, migraine, stroke, and traumatic brain injury (

16). The subgroup of patients who received psychiatric consultation was a median of 5 years older than the total sample, with a higher proportion of females and a higher mortality rate (33% versus 28%).

Physicians treating PRES and liaison psychiatrists should be alert to psychiatric comorbidities. In addition, multidisciplinary staff should consider PRES as a rare, organic differential diagnosis for acute mental state changes, especially when PRES coincides with neurological symptoms, hypertension, or medical comorbidities. Physicians treating PRES should assess for post-PRES psychiatric symptoms, to consider whether consultation-liaison psychiatry, specialist substance use, or community psychiatric follow-up may enhance recovery.

Given these rates of psychiatric comorbidity, it is striking that mental health comorbidity is near-absent from literature on PRES, which focuses on neuroimaging, neurological sequelae, treatment, and prognosis. This is surprising, given the association between neuropsychiatric symptoms and temporo-limbic network lesions, which are not uncommon in PRES. Despite the term reversible, residual infarcts and subsequent leukomalacia are recognized sequelae of PRES (

17), supporting the likelihood of longer-term psychiatric symptoms in a proportion of patients, which is well recognized in acute neurological disorders such as encephalitis (

11,

12).

As expected, our study sample had high rates of underlying medical comorbidity. Worldwide, depression prevalence is higher among people with chronic conditions (

18), including neurological (

19) disorders. The most common reasons for psychiatric services referral in our sample were alcohol and intravenous drug addictions, acute psychosis, depression, suicidality, and refusal of medical treatment due to delirium or agitation. There were few or no referrals for severe anxiety, long-standing psychotic illnesses, bipolar illness, intellectual disability, and personality or eating disorders. Perhaps during critical illness treatment and follow-up, only markedly acute psychiatric symptoms were detected by physicians and referred for assessment. It is not possible to definitively quantify the extent to which some psychiatric morbidity predating PRES onset may have gone undetected. Such morbidity would be expected to be increased over the population baseline in the context of chronic medical illness. The United Kingdom National Health Service provides open access to family health practitioners, and therefore most moderate to severe mental disorders are recorded. Substance use disorders, however, may not always be identified, treated, and recorded by health care services.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide preliminary support for our clinically informed hypothesis of elevated psychiatric morbidity among individuals following PRES onset, which requires more widespread, prospective investigation. One strength of our study is its relatively large sample size, drawn from a broad, diverse, densely populated region of South London in a teaching hospital with expertise in a range of relevant medical disorders. One limitation is its pragmatic, retrospective audit design, dependent on routinely documented free-text clinical records. Future research and PRES case series should investigate psychiatric comorbidity and sequelae systematically, including the premorbid period, to elaborate on these findings. Perspectives of patients and their care givers on pre- and post-PRES mental states, as well as longitudinal follow-up of neuropsychiatric outcomes, would be particularly informative.