Exercise can improve and strengthen various aspects of brain structure and function, such as volume, connectivity, neurogenesis, neuroplasticity, and cognition (

26–

30). In addition, exercise has numerous benefits for the overall mental health of individuals, including lowering the risk for neurodegenerative diseases. However, the specific neural and peripheral physiologic mechanisms linking exercise to these positive effects in the central nervous system (CNS) remain unclear (

26,

30,

31).

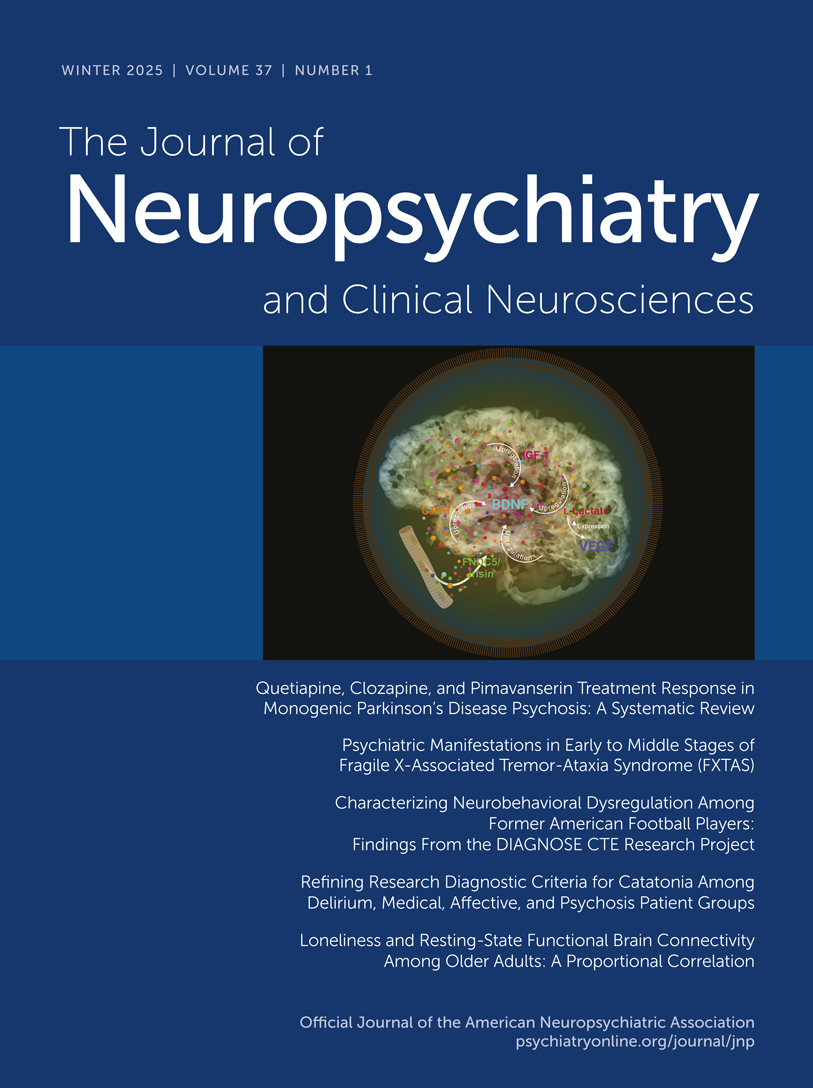

Myokines belong to a specific group of exerkines-signaling moieties. They correspond to a subset of muscle-derived bioactive molecules (e.g., cytokines, small peptides, polypeptides, growth factors, and organic acids) that perform important functions, mediating cognition and other brain functions in response to exercise (

1,

7,

10). Myokines are synthesized and secreted by myocytes in response to skeletal muscle activation and contractions primarily induced by exercise, specifically high-intensity resistance training (

Figure 1A) (

2–

5).

After their (transient or continuous) secretion, myokines are physiologically active in an autocrine, paracrine, or endocrine fashion in other tissues and organs of the body (e.g., bones, adipose tissue, liver, and brain) (

6). However, most myokines can have paracrine functions, and some can cross the blood-brain barrier, facilitating signaling pathways and potentiating exercise-induced brain benefits (

6–

9). Myokines also exert important functions as communication conduits between muscles and many other tissues (

32). In the CNS, they constitute an important biomolecular substrate for cross-talk between skeletal muscle and the brain via an integrative endocrine loop, the muscle-brain axis (MBA) (

Figure 1B–C) (

7,

9–

12).

Hundreds of myokines have been described in the literature. Some of those most relevant to the brain include brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), insulin-like growth factor–1 (IGF-1), cathepsin B (CTSB), fibronectin type III domain–containing protein 5 (FNDC5)/irisin,

l-lactate, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (

3,

7,

8).

Myokines have broad bioactivity and physiologic versatility (i.e., autocrine, endocrine, and paracrine capabilities) in restoring metabolic balance and health (

7). This realization has led to a greater understanding of the relevance of muscle tissue and exercise for human health (

3). However, despite their general health benefits, not all myokines can potentiate brain effects. Only a few can exert neurologic functions and signal neurophysiologic processes (

6,

7,

10,

12). However, the specific functions of myokines remain poorly understood (

7).

Myokines and Their Effects in the Brain

It seems that a continuous cross-talk takes place between the muscular and nervous systems. The brain is the ultimate sensor for exercise and other activities (

3,

9). Many exercise-induced myokines (e.g., BDNF, IGF-1, and CTSB) can improve brain tissue and cognitive function, including memory (

6,

13,

29). Skeletal muscle myokines induced by exercise can act on brain structures, such as the hippocampus, improving neurogenesis, mood, memory, and learning (

Figure 2A) (

9,

13). Furthermore, some myokines (e.g., BDNF) may slow progression of chronic diseases among older people (e.g., sarcopenia, Alzheimer’s dementia, and depression), preventing cognitive decline and improving neurogenesis, mood, and motor function (

22).

BDNF

BDNF is present at high concentrations in the human CNS. Approximately 70%–80% of circulating BDNF, at rest and during exercise, originates from the brain, potentially mediating (in part) its positive effects on cognition (

13,

33,

34). BDNF appears to work in conjunction with other important myokines, such as CTSB, IGF-1, and FNDC5, which in turn amplifies its bioavailability and brain-signaling capabilities. These myokines seem to act synergistically as MBA molecular substrates of exercise-induced neuroplasticity (

Figure 2B) (

6,

9). Exercise-induced BDNF in skeletal muscle can cross the blood-brain barrier, further supporting the potential benefits of BDNF on cognition and mood. These effects appear to depend on the type of exercise and its duration, because levels of BDNF increase with acute and intense exercise sessions (

9). Preliminary results suggest that BDNF might be a promising predictor of intervention responses among individuals with major depressive disorder (

35).

IGF-1

IGF-1 acts as an upstream regulator of BDNF and helps to regulate gene expression involved in BDNF-related neurogenesis (

14). Both myokines are important CNS regulators, promoting the development and maintenance of neural circuits and other pathways (

6,

36). IGF-1 is synthesized in various structures, such as the cortex, cerebellum, hippocampus, and hypothalamus (

37). When produced peripherally (in the liver and muscles), this molecule can access the brain by crossing the blood-brain barrier and the choroid plexuses (

37,

38).

IGF-1 has a wide range of functions in the brain, such as neurogenesis, neuroprotection, neuroplasticity, regeneration, synaptogenesis, and antiapoptotic signaling, among others (

37). Exercise-induced IGF-1 levels rapidly rise in humans in response to acute sessions of high-intensity physical activity (

38,

39). Recent reviews and reports from studies in rodents have indicated that IGF-1 has antidepressant effects (

Figure 2A–B) (

40–

42). However, the role of IGF-1 as an antidepressant in clinical studies requires further investigation (

35).

CTSB

CTSB is a member of the lysosomal cysteine protease family and is synthesized, upregulated, and secreted from muscle cells; therefore, it is considered a myokine (

6). Exercise-induced CTSB has been associated with improved brain function (

6). In mice, increased CTSB has been linked to spatial object recognition (a function of hippocampal-dependent memory) after long-term running sessions, suggesting that CTSB mediates the effects of exercise on cognition (

29). Another study in mice reported that skeletal muscle–derived CTSB improves cognitive function by upregulating BDNF and doublecortin in the hippocampus, which further mediates neuroplasticity, neuronal survival, and migration (

Figure 2A) (

15).

In a study of 40 healthy middle-aged people (

43), higher concentrations of circulating CTSB were associated with increased cognitive control and faster information processing speed. These findings appear to link CTSB to both cognitive control and neuroelectric function in the brain. However, the medical evidence on benefits of exercise-induced CTSB is still scarce. More clinical investigations are essential to better understand its multifactorial roles, especially in the CNS (

6).

FNDC5/Irisin

Irisin is another myokine whose synthesis (by proteolytic cleavage from its precursor FNDC5) and secretion are induced by exercise. In humans, about 70% of irisin is produced in skeletal muscle cells, with the remainder generated in other tissues, such as the brain and white adipose tissue (

6,

31). High-intensity exercise increases irisin secretion (

44). In one study (

45), adolescent males had higher circulating irisin concentrations than their female counterparts after aerobic exercise and at rest. However, it is not clear whether these sex differences persist throughout adulthood (

44,

45). Once released from muscles, irisin can access the brain by crossing the blood-brain barrier (

46). It appears to have an important role in mitochondrial function, inflammatory responses, metabolic diseases, and aging (

6). In addition, irisin seems to be involved in CNS regulatory processes, such as neurogenesis, neuroprotection, neurotrophic factor imbalance, insulin resistance, and oxidative stress (

Figure 2A) (

44,

47). In the brain, exercise appears to be a powerful potentiator of hippocampal FNDC5 (along with BDNF) via the peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha and the estrogen-related receptor alpha (PGC-1α-Errα) transcriptional signaling pathways. Therefore, exercise-induced FNDC5 expression upregulates hippocampal levels of BDNF (

Figure 2B) (

16).

Recent findings from rodent studies suggest that exercise-inducible irisin is an important regulator of cognitive processes, which may have translational potential (

44,

48,

49). FNDC5/irisin gene deletion affects cognitive function among patients with Alzheimer’s disease (

49); another study linked irisin to episodic memory and global cognition among individuals at risk for dementia (

50). A clinical trial reported positive correlations between serum levels of irisin and amyloid beta, as well as improved metabolic and neurocognitive indices among overweight individuals with genetic risks for Alzheimer’s disease (

51).

In addition, findings from a study in rats suggest that irisin may offer therapies for alleviating depression (

52). Other studies have indicated that exercise-induced irisin acts on the hippocampal PGC-1α–FNDC5/irisin pathway, reducing symptoms of depression (

53–

55). Overall, exercise-induced irisin (peripherally and in the CNS) is relevant in certain neurologic disorders, but its potential clinical implications remain unclear (

6,

44).

l-Lactate

l-Lactate production is triggered by intense exercise conditions and ischemia. Among adults, about half of the daily production of

l-lactate occurs within the muscles and skin, with the remainder produced in red blood cells (20%), brain (20%), and intestines (10%) (

56). Once released,

l-lactate penetrates the blood-brain barrier via monocarboxylic acid transporters to enter the brain. These transporters also facilitate its access to other tissues and organs (

5,

57). Typically,

l-lactate transfers from its sites of production to other locations depending on physiologic demand (e.g., from glia to neurons, between different myofibers in skeletal muscle, and from skeletal muscles to the brain) via peripheral blood circulation (

57).

l-Lactate has been described by some researchers as the preferred form of energy for metabolic processes in the brain (

58). Glucose enters astrocytes and oligodendrocytes and produces

l-lactate via glycolysis.

l-Lactate is then produced by glycogenolysis and glycolysis. Exogenous

l-lactate enters neurons via monocarboxylate transporter 2, where it serves as a metabolite and is converted to pyruvate, thus producing energy within the neuronal mitochondria (

18).

Monocarboxylic acid transporter–mediated transport of

l-lactate inside hippocampal neurons intensifies BDNF expression via induction of PGC-1α and silent information regulator 1 transcriptional signaling pathways. Increased BDNF expression in turn induces FNDC5 signaling, a process that improves spatial learning and memory in mice (

Figure 2B) (

17). A novel

l-lactate receptor, hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 1, was recently discovered in the brain, providing an additional mechanism by which

l-lactate can enter nerve cells and regulate neural function (e.g., similar to neurotransmitters) (

18). Furthermore, hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 1 is linked to neuronal firing activity, possibly facilitating memory and learning processes (

19,

59).

l-Lactate has also been linked to multifunctional signaling capabilities with theoretical potential for clinical and psychiatric interventions (

18,

58,

60). Peripheral

l-lactate administration was associated with antidepressant effects in rodent models (

23,

24,

61). Furthermore, a recent review of clinical studies (

18) found increased brain

l-lactate levels among patients with depression compared with those of healthy control subjects. Therefore, exogenous

l-lactate administration might lead to positive clinical outcomes, including improved mental health status (

18).

VEGF

VEGF is also produced by myofibers during exercise and can cross the blood-brain barrier (

25). VEGF has been linked to angiogenesis and the maintenance of normal blood circulation in the hippocampus (i.e., cerebrovascular blood flow) in response to acute exercise. An important positive effect of VEGF is promoting hippocampal neurogenesis, activating the proliferation of neural stem cells in the dentate gyrus (

62). A study in mice (

20) reported increased levels of exercise-induced VEGF in the hippocampus, seemingly connected to the benefits of exercise on learning and memory.

VEGF expression in the brain appears to be increased by

l-lactate. This observation provides further evidence that VEGF and other myokines (e.g., BDNF and irisin) act together as muscle-to-brain cross-talk molecules that potentiate neuroprotection, neurogenesis, increased signaling, and other benefits of the MBA (

21). Furthermore, VEGF is responsible, in part, for the higher numbers of neuronal precursor cells and larger hippocampal volume that result from exercise (

Figure 2A–B) (

25).

Conclusions

Exercise generates important neurophysiologic effects in the brain. Myokines are exercise-induced neuroactive substances similar to neurotransmitters and have a key role in the muscle-brain endocrine loop. They seem to sustain (at least in part) some of the physiologic mechanisms underlying the positive effects of exercise in the nervous system.

Myokines, such as BDNF, IGF-1, CTSB, FNDC5/irisin, and l-lactate, appear to exhibit synergistic physiologic mechanisms, allowing them to amplify each other’s signals and functions via reciprocal biochemical pathways. Understanding the specific molecular mechanisms of myokines is essential for the development of new pharmacologic therapies and complementary exercise-based interventions, particularly for older individuals, those with physical impairments, and individuals with brain disorders.

In addition, the direct and indirect effects of myokines on the peripheral and autonomic nervous system among healthy individuals remain unclear and require more in-depth investigations. Although these neuroactive substances hold physiologic potential, a significant gap in the scientific evidence remains regarding possible benefits for patients with neurologic, psychiatric, or neurodegenerative diseases.