Both depression and apathy are common psychiatric manifestations in various neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders, including Parkinson’s disease, dementia, schizophrenia, and traumatic brain injury (TBI) (

1–

7). However, depression and apathy are often mistaken for each other in both clinical and research settings. This confusion primarily stems from the definition of depression itself. The DSM-5, a mainstream psychiatric diagnostic system, defines depression as “depressed mood and/or a markedly diminished interest or pleasure” (

8). As this definition indicates, depression is a complex of heterogeneous symptoms. In contrast, apathy, defined as a lack of motivation (

9), is a narrow concept that refers to specific symptoms. As a result, apathy is included in the definition of depression as a partial constituent. Nonetheless, in neuropsychiatry, some authors have emphasized that apathy should be considered separately from depression (

10). This view has been supported by the fact that these disorders respond to different interventions, including pharmacotherapy (

7,

11,

12).

Several studies have examined this issue among patients with neurological and psychiatric disorders (

13–

18) and have successfully demarcated apathy from depression among patients with unipolar and bipolar depression (

13), geriatric depression (

18), and Alzheimer’s disease (

16). Although patients with TBI have a high prevalence of both depression and apathy (

19,

20), few studies have examined this issue. TBI is a serious public health problem that causes a variety of neurological and neuropsychiatric sequelae. Depression and apathy can lead to poor outcomes because of difficulties with rehabilitation or social integration and loss of vocational opportunities (

21,

22). However, among patients with TBI, psychiatric sequelae vary depending on the severity of and time since injury (

23,

24). Moreover, in some cases, the sequelae of psychiatric symptoms are difficult to assess because of patients’ lack of awareness (

25). The few studies that have examined this issue among patients with TBI have found that the somatic component of depression can be distinguished from the other components of depression, although apathy has not been reported as an independent component (

26,

27).

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the possibility of extracting the component of apathy from depression syndrome among patients with TBI. First, a cluster analysis was applied to data collected by using the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II) to examine whether the apathy component of depression is discriminable from its other components. Second, the validity of the extracted putative apathy subcomponent was examined. To do this, the correlation of this subcomponent score with a gold-standard apathy score, namely, the Starkstein Apathy Scale (AS) score, was determined. Finally, to further validate the significance of this subcomponent, the relationship between the apathy subcomponent score and daily activity data collected by using a self-monitoring life log was assessed.

Discussion

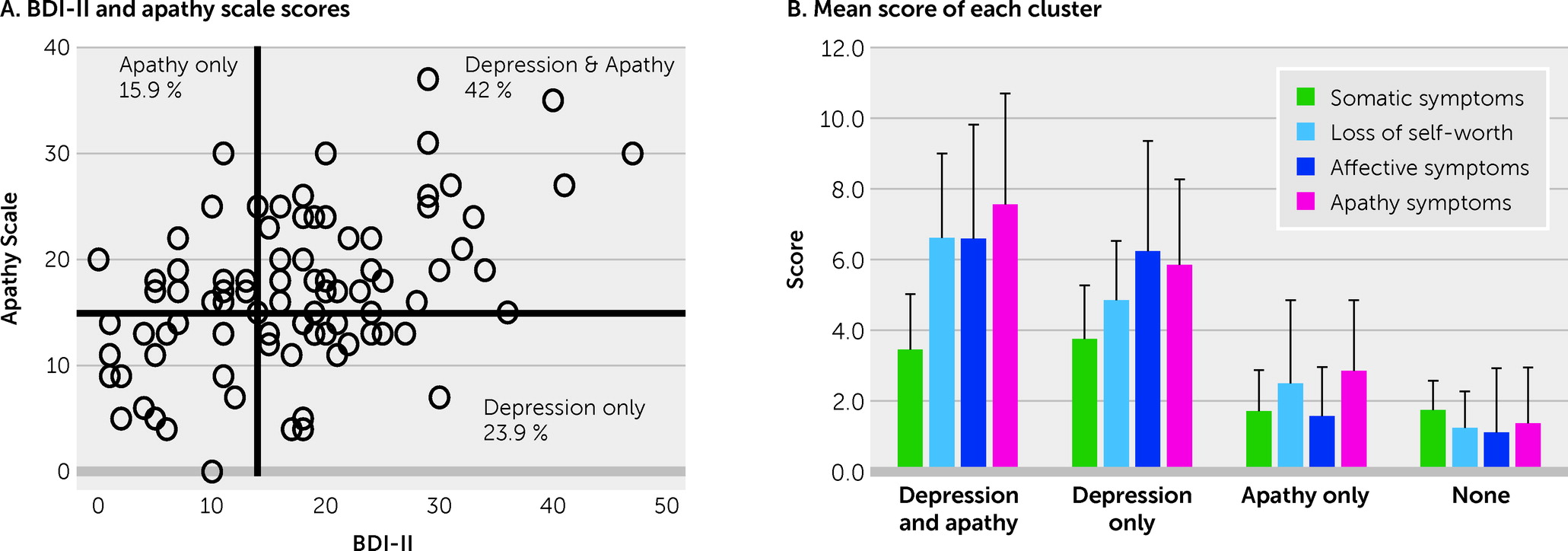

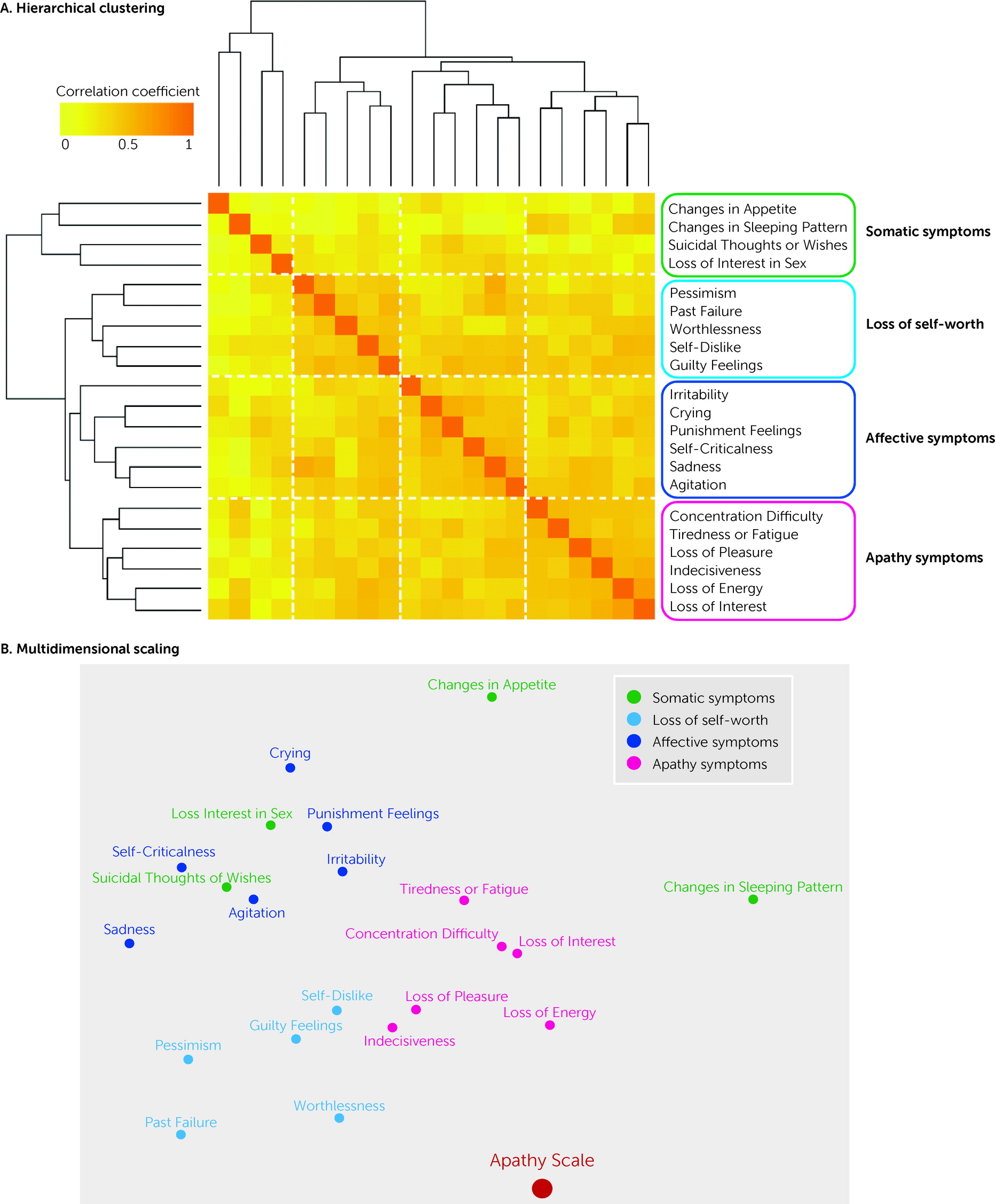

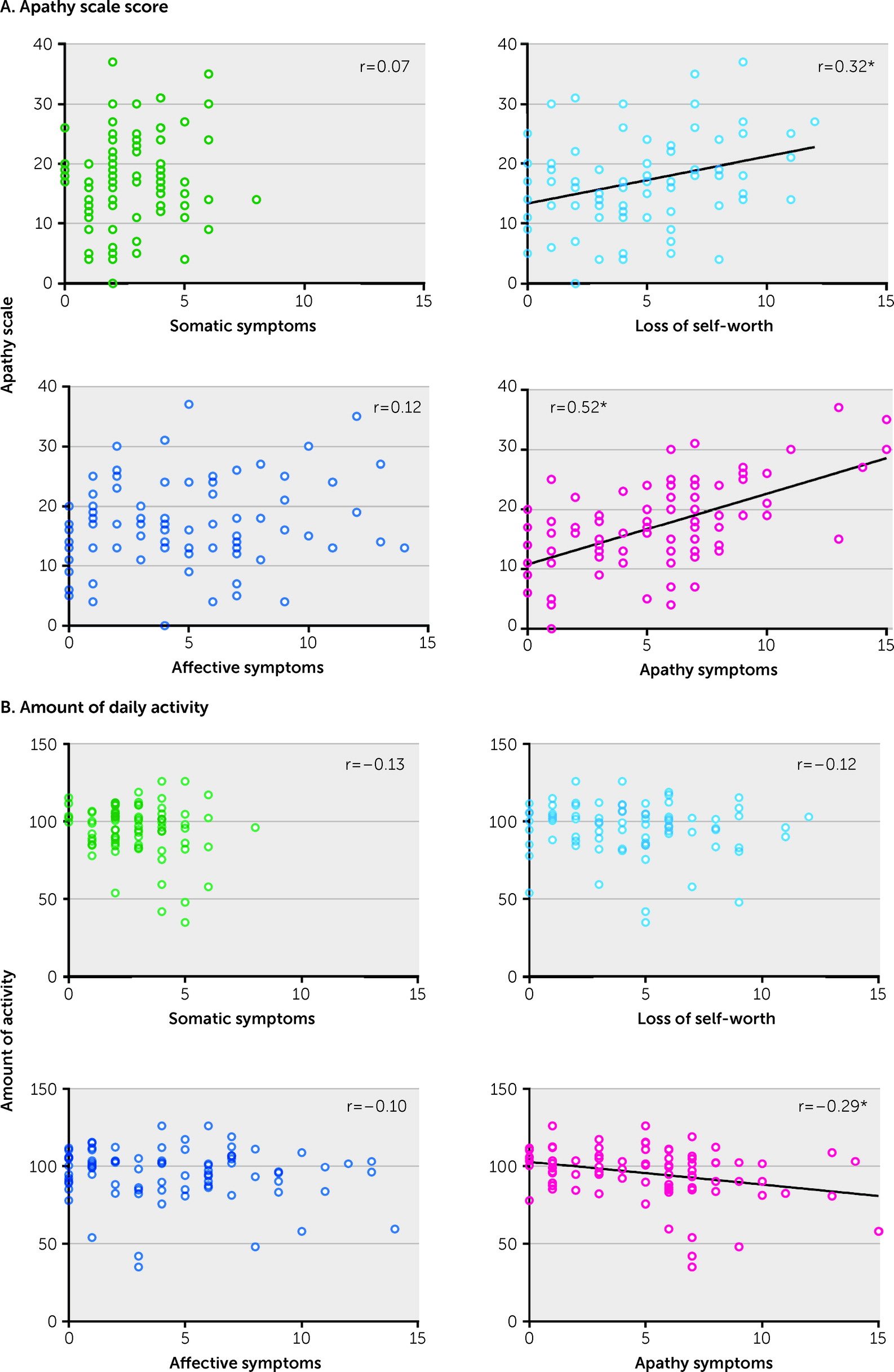

The primary aim of this study was to determine whether apathy can be distinguished from the other components of depression among patients with TBI by using a common measure of depression. Nearly half of the patients had symptoms of both depression and apathy. The hierarchical clustering revealed that depressive symptoms measured by the BDI-II could be divided into four separate clusters (somatic symptoms, loss of self-worth, affective symptoms, and apathy symptoms). Among these clusters, the apathy symptom subscore showed a robust correlation with AS score. In addition, the apathy symptoms subscore was significantly correlated with the amount of daily activity, whereas no such relationship was seen with the subscores of the other clusters. Although many patients with TBI have symptoms of both depression and apathy, these results suggest that the apathy component is separable from broader depressive symptoms.

The BDI-II results revealed that 65.9% of patients with TBI in the present study had mild to severe depression. In previous studies, the reported prevalence of depression has been variable, ranging from 6% to 77% (

19,

21,

40). The relatively higher prevalence reported in this study might be due to use of the BDI-II to diagnose depression rather than semistructured interviews of the DSM. However, it is also likely due to the characteristics of this study’s participants, who were recruited from the outpatient clinic of a university psychiatry department, which inevitably led to a higher percentage of patients with psychiatric symptoms. As for apathy, previous studies have reported a prevalence ranging from 20% to 71% among patients with TBI (

20). A relatively high prevalence (57.9%) was observed in this sample, which again may reflect the characteristics of participants drawn from an outpatient psychiatric clinic. It should also be noted that 42% of patients presented with both depression and apathy, and 23.9% and 15.9% had only depression or only apathy, respectively. This might indicate that apathy and depression frequently co-occur among patients with TBI, and pure apathy, or depression without apathy, are less frequent.

By using hierarchical clustering, the component of apathy was successfully extracted from the item-to-item analyses of the BDI-II. This extracted “apathy cluster” of the BDI-II included six symptoms. Because some of the items, such as “loss of energy,” were common or related to those of the AS (

34,

41), it is not surprising that the apathy subscore showed a robust correlation with the total AS score.

Although provisionally referred to here as an apathy cluster, the following conceptual issues should also be noted. First, among the six items included in this cluster, four are considered to be motivational symptoms, but the other two (“concentration difficulty” and “indecisiveness”) are more properly regarded as symptoms of subjective assessment of one’s own cognition. Second, among the four motivational symptoms, “loss of pleasure” and “loss of interest” are more appropriately considered anhedonia rather than apathy. Further conceptual and empirical fractionization within the apathy cluster is needed in future studies. Previous work has successfully distinguished apathy from depression among patients with depressive disorder or dementia (

13,

16–

18), but not among patients with TBI (

26,

27). As noted earlier, the prevalence of apathy with depression was high among participants in this study, which may have facilitated successful separation of apathy from depression in this relatively small sample.

Moreover, the loss of self-worth subscore also correlated with the total AS score. Of the broader symptoms of depression, this cluster might be relatively similar to apathy. A somatic cluster was identified in this study, similar to a previous study that used a factor analysis of the BDI scores among patients with TBI (

26). Indeed, changes in sleep, appetite, or libido may occur among patients with TBI, independent of depression (

19). Thus, it is important to pay clinical attention to the symptoms in this cluster because they should be treated separately from psychiatric symptoms, especially among patients with TBI.

One of the novel findings of our study is that the apathy symptoms subscore was correlated with amount of daily activity, whereas the other subscores had no relationship with it. Depression includes not only symptoms that decrease activity but also symptoms that increase activity, such as agitation or irritability. In this study, the apathy component of the various depressive symptoms reported was associated with a decreased amount of activity. In addition, in a supplementary analysis of the effects of medication, no difference was found in the amount of activity between patients who were and were not taking medication. Therefore, decreased daily activity is not solely attributable to oversedation.

Among patients, apathy is often accompanied by a lack of insight (

42). Thus, it is widely believed among clinicians that the self-assessment of apathy is unreliable, and objective assessments by clinicians or relatives are thus indispensable. However, the correlation with real-life activity supports the validity of subjective ratings in the assessment of apathy. Although self-reports may not be reliable for severe apathy, they may be able to make a fair estimation of real-life apathy symptoms among those with mildly to moderately severe apathy.

Our study has several limitations that should be considered. First, self-reported questionnaires to measure psychiatric symptoms and daily activity were used. Although the findings support the validity of using a subjective rating scale, it might not be suitable for those with more severe apathy, because the lack of insight might hinder reliable self-assessment. Moreover, in addition to lack of insight, the present analyses did not include neuropsychological impairments as covariates. Cognitive functions such as memory may affect the assessment of psychiatric symptoms. Future studies should seek to replicate or modify the present findings using other assessments of apathy. Second, because of the clinical settings of this study, most patients were in the chronic phase of TBI and likely to have psychiatric symptoms. Thus, the present findings may not generalize to the population with TBI as whole, particularly to those who are not receiving care in a psychiatric clinic. Hence, this study should be regarded as preliminary and should be reexamined among a larger sample that also includes patients with mild psychiatric symptoms. Third, patients with various types of injury were included in the present study, including persons with focal lesions or diffuse axonal injury; moreover, lesion locations among patients with focal injury were diverse. Therefore, the relationship between lesions and symptoms could not be studied in this relatively small sample of participants. Future studies are needed to address whether the clusters isolated from depressive symptoms have different structural or functional neuroanatomies.

Overall, the present findings support the thesis that apathy is clinically separable from broader depressive symptoms. On the basis of the present findings, decomposing heterogeneous depressive symptoms would be useful for selecting appropriate treatments for individual patients. This is important because the pharmacological options for treating apathy are different from those used to treat depression (

11,

36,

43). Nonpharmacological interventions for apathy and depression are also fundamentally different. For example, as a general rule, patients with depression should not be overencouraged to do things: for patients with a substantially negative mood, dysphoria in particular, it is advisable to motivate them gently, delicately, and gradually in daily activities after maximal amelioration of the symptoms with medication. However, it is reasonable to encourage patients with apathy to participate in daily activities or rehabilitation in a more straightforward manner. Considering that neuropsychiatry specialists are not always available in many clinical settings, the use of self-rating scales might help to guide the choice of clinical intervention.