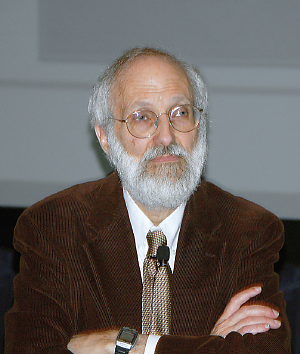

Susceptibility to alcohol use disorders is a complex mix of genetics and family environment now being revealed with the combined tools of epidemiology and molecular genetics, said Kenneth Kendler, M.D., delivering the annual Mark Keller Honorary Lecture at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism in Bethesda, Md., in November.

Genetic epidemiology indicates that heritability of alcohol use disorders runs at between 50 percent and 60 percent, said Kendler, a professor of psychiatry and human genetics at Virginia Commonwealth University.

By comparison, anxiety and depression are about 20 percent to 40 percent heritable, and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are 60 percent to 80 percent heritable.

Heritability is not a static factor, but interrelates with developmental and environmental factors to affect an individual’s risk of illness, he explained. “Heritability represents the proportion of differences of a particular trait, in a specific population, at a specific time, as a result of genetic differences in that population at that time.”

Men and women demonstrate similar rates of genetic-influenced factors, shared environments of childhood, and unique environments they encounter in adulthood, according to several studies by Kendler and his collaborators in Europe and the United States.

The effects of social factors on substance use can vary with the substance studied, he pointed out. A study of 8,935 male Swedish twin pairs over the first half of the 20th century found no differences in rates of alcohol dependency across wide changes in the price and availability of alcohol in Sweden. By contrast, heritability of tobacco use among Swedish women over the same period increased due to relaxation of social strictures and increased availability.

One’s angle of view can reveal different aspects of the disorder, Kendler noted. Multiple twin studies in the United States and Norway show that the genetics of alcohol use disorder are closely allied with those for other externalizing diagnoses, such as drug abuse, conduct disorder, and antisocial personality disorder, said Kendler. However, when considered in terms of environmental factors, alcohol disorders appear more closely related to internalizing disorders.

The seven DSM-IV criteria for alcohol use disorders reflect not a single set of risk genes but actually three distinct sets of genes, Kendler has hypothesized. These groupings of genes include those that affect heavy use and tolerance, social dysfunction and loss of control, and withdrawal symptoms or continued use in the face of alcohol-related problems.

“Genes are developmentally contextual,” he said.

Environment counted for all the variation up to age 14 or 15, he said. “But as you age, the shared environment becomes less important, and genes become more important.”

But just how do those family influences work out? Do parents teach factors that lead to alcoholism or just transmit it through their genes?

Twin studies indicate that about 88 percent of the pathway comes from environmental sources, with the rest arriving via a genetic pathway, said Kendler.

The proportion of influence attributable to the shared home environment steadily drops over the teenage years, even as that for genetics steadily rises, and the unique personal environment’s role rises somewhat during those years but remains relatively stable.

One reason is that parents can control access to alcohol at home, but once children go out on their own, they can act more easily on a genetically impelled desire for alcohol. Also, hanging out with a “bad crowd” can potentiate the genetic factors, he noted.

“Both peer-group deviance and alcohol availability are themselves influenced by genetic factors,” he said. “Whether a child stays home and watches ‘Masterpiece Theatre’ or goes out in the evening and gets into fights is largely driven by genes.”

On the positive side, prosocial effects such as parental monitoring, religiosity, stable neighborhoods, or marriage can lessen the effects of genetics on risk for alcohol use disorders.

The steady elaboration of the hybrid discipline of genetic epidemiology can thus increase understanding of how genes interact with environmental factors over the course of development to influence the likelihood of alcohol use disorders. ■