Often, when people think of schizophrenia, they picture it as an illness that tends to strike teens or young adults. But nearly 1 in 4 individuals who develop schizophrenia does so later in life, research by Jilip Jeste, M.D., and others has found.

And now, in what may help explain why some people develop the illness in middle age, researchers have linked a major component of the body’s immune response with late-onset schizophrenia.

The senior researcher was Borge Nordestgaard, M.D., a professor and chief physician at Copenhagen University Hospital in Denmark. Study results were published online August 31 in Schizophrenia Bulletin.

Individuals with autoimmune diseases and severe infections have been found to have a heightened risk of developing schizophrenia compared with people without such diseases or infections. Moreover, there is increasing evidence that patients with schizophrenia have in their blood elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines—immune system molecules that initiate an inflammatory response to fight disease. This has led some researchers to suggest that the immune system, and cytokine-provoked inflammation specifically, might be involved in the schizophrenia disease process.

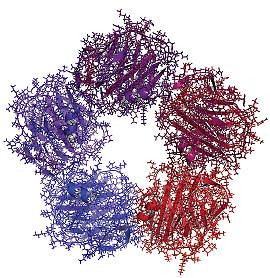

Now enter C-reactive protein, an immune system component that is released by the cytokines in reaction to infection and whose role is to bind to bacteria or dying cells and activate the complement-system arm of the immune system. This protein also mirrors the amount of inflammation that is triggered by the immune system. Nordestgaard and his colleagues suspected that elevated blood levels of C-reactive protein might be implicated in late-onset schizophrenia and decided to test this hypothesis.

Their study cohort included some 79,000 individuals aged 20 to 100 whom they followed over a 20-year period. In total, 238 individuals received a diagnosis of schizophrenia during that period; the average follow-up to a diagnosis was seven years.

The researchers found that baseline elevated blood levels of C-reactive protein were associated with a sixfold to 11-fold increased risk of developing late-onset schizophrenia, even after adjusting for several possible confounders. They also found that individuals with schizophrenia had significantly higher levels of C-reactive protein in their blood than did individuals without schizophrenia, again after controlling for possibly confounding factors.

The researchers thus believe that C-reactive protein is implicated in late-onset schizophrenia and suspect that it might contribute to the schizophrenia disease process. One possibility, they suggested, is that the protein disrupts the blood-brain barrier, allowing other immune system players, such as pro-inflammatory cytokines and/or autoantibodies, to flood the brain and create havoc there. The protein has been shown to disrupt the blood-brain barrier in laboratory studies of animals.

“The association of C-reactive protein with late-onset schizophrenia is very robust, even after health-related confounds are addressed,” William Carpenter, M.D., told Psychiatric News. Carpenter, a schizophrenia expert, is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland and director of the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center.

However, “The immediate challenge with this report is the causal direction,” he pointed out. “Is elevated C-reactive protein causing a porous blood-brain barrier, permitting entry for pro-inflammatory cytokines, for example, or are variables associated with schizophrenia, such as therapeutic or abuse drugs, causing the C-reactive protein elevation?”

But assuming that C-reactive protein is contributing to schizophrenia, he indicated, then it helps support the “inflammatory pathophysiology hypothesis in schizophrenia”—a hypothesis that “is opening new opportunities for etiology and therapeutic discovery.”

For example, during the past five years, scientists at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, as well as scientists in England, Israel, and Japan, have reported that the antibiotic minocycline countered not just positive symptoms, but negative ones in some schizophrenia patients. Minocycline is known to be capable of fighting inflammation and crossing the blood-brain barrier into the brain. So it might be able to reduce inflammation in the brain (Psychiatric News, August 17, 2012).

There is also research evidence suggesting that infection and autoimmune disease can increase the risk for mood disorders, and if so, the mechanism at work might be inflammation created by an activated immune system (Psychiatric News, July 23). Indeed, the same immune system components that are associated with an increased risk for schizophrenia—such as C-reactive protein—might also increase risk for mood disorders, Nordestgaard told Psychiatric News, since he and his colleagues reported in the February JAMA Psychiatry that a high level of C-reactive protein is a strong risk factor for depression.

The study was funded by Herlev Hospital, Copenhagen University Hospital, and the Danish Council for Independent Research, Medical Sciences. ■