Many life-changing events in American history were commemorated in 2013, including the 50th anniversaries of the passage of President Kennedy’s Community Mental Health Act, his assassination a few months later, and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

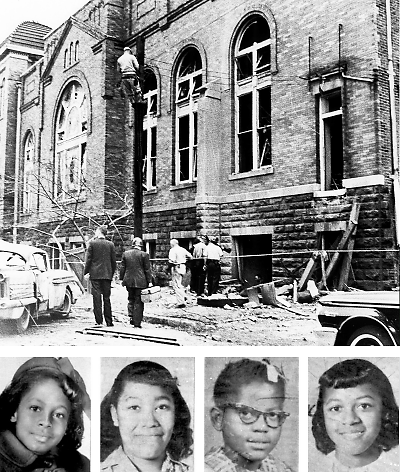

The year also marked 50-year observances for events that were representative of a tumultuous time in American history for African Americans, such as the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, an act of racial hatred that killed four young girls in Birmingham, Ala., on September 15, 1963.

On November 12, APA’s Office of Minority and National Affairs (OMNA) partnered with the American Association of Community Psychiatrists and the Alabama Psychiatric Physicians Association to present “Transcendence and Resilience Following Trauma,” commemorating the triumph of African Americans after the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church. The event, a program of the OMNA on Tour series, took place at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, with over 100 attendees of all ages and races who came to listen to civil-rights activists and psychiatrists share their personal stories of this American tragedy.

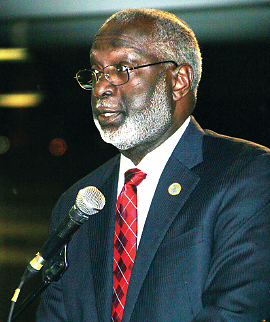

Former U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D., served as the event’s keynote speaker and spoke about growing up in Alabama during an era when racism was supported by harsh state laws that restricted the freedom of African-American citizens.

“I grew up during a time when black children died at home because they could not be admitted to a hospital,” said Satcher, who explained that because of racism’s many manifestations—which included inadequate health care for minorities—and his personal life experiences, he was prompted to join forces with those committed to eliminating health disparities in this country.

“To eliminate the disparities in mental health and other areas of health, we needed—and still need—people who care about other people, regardless of race and ethnicity,” he emphasized.

Satcher entered medical school at Case Western Reserve University in 1963, just weeks before the Birmingham church bombing. Satcher—who in 1999 was the first surgeon general to issue a report on mental health—said that mental health can be defined as “the ability to deal with adversity.”

“I can’t think of any greater adversity than that of a church bombing that killed four little girls,” he said.

Satcher said that having discussions about the emotions associated with that tragic event is what has allowed, and will allow, people to heal.

Anita Everett, M.D., director of the Division of Community and General Psychiatry at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center and an APA Trustee, agreed.

“Talking about events of the civil-rights movement is very important,” she told Psychiatric News, as she reflected on how her father found himself caught in the middle of the movement when he defied segregation laws and allowed blacks to be served at the lunch counter of a department store he managed in Huntsville, Ala., in 1963.

“It was only in recent years that my family started talking about this story,” said Everett who explained that her father disclosed years later that he had received threatening phone calls for his participation in Huntsville’s desegregation effort. “My father is a part of a generation that didn’t speak of emotions, so having him talk about his role in the past has been valuable for our family,” Everett said.

Kenneth Thompson, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, speculated that in 1963 there was likely no conversation addressing how the events—such as the church bombing—that shaped the civil-rights movement would impact the mental health of blacks and whites living in Southern communities.

“The blast of the bomb doesn’t go away; it echoes. Are these people still traumatized today? If so, how do they express it?” asked Thompson, who specializes in treating those who have endured traumatic events. “This was an act of terrorism,” and at the time there was no diagnosis for what is now known to be posttraumatic stress disorder, he told Psychiatric News.

According to Annelle Primm, M.D., MPH, APA deputy medical director and director of OMNA, the event opened a door for issues that needed to be discussed in Birmingham. “Many people from the local area felt the need to remain silent about this tragedy,” said Primm during an interview. “The program achieved the goal of creating a safe and welcoming environment in which attendees felt comfortable enough to break their silence and provide personal narratives on how they were affected by the bombing and related incidents.”

Though the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing and much of the civil-rights movement occurred 50 years ago, Primm concluded that it is beneficial—and never too late—to share stories about coming to terms with trauma and working toward healing. ■

A video interview with Kenneth Thompson, M.D., on healing from trauma after the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing can be accessed at

http://youtu.be/JCnodiYPz8E;an interview with Anita Everett, M.D., on her father’s involvement in the Civil Rights Movement in Alabama can be accessed at

http://youtu.be/yokwFNVbtEI.